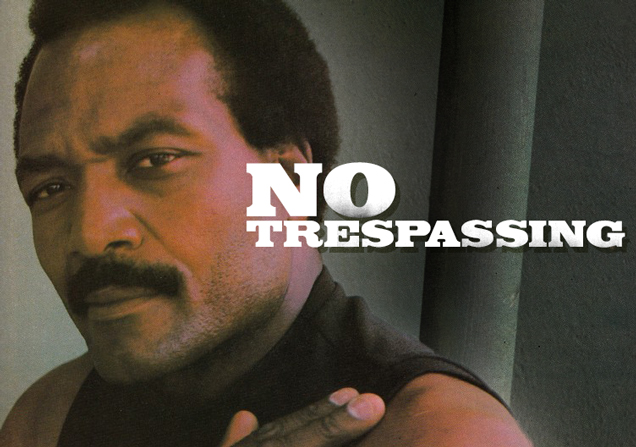

“The old lion is still a bad mother,” he said. “He just wants to roam. Leave him alone. He’s fading, but he’s still a lion.”

St. Simons Island lies four miles off the coast of southern Georgia, connected to the mainland by a two-lane road, separated by saw grass and swamp.

It’s a quiet place with miles of hard-sand beaches, a place the big developers and the resort hotels somehow missed, where people work for a living and nobody has decided yet that you and your dog can’t drink beer on the beach.

For the first nine years of his life, Jim Brown lived on the island in the care of his grandmother and great-grandmother. He still calls the great-grandmother the love of my life. “She would say, ‘I love you forever,’” he said, “and for as long as I was on St. Simons, there was always the ocean and the white sand, and there was never a question of belonging.”

Jim Brown is 45 years old now. It hasn’t been like that for him since.

The island is a town. There is a main street, a couple of small shopping centers, churches, bars. A few rich neighborhoods, a few dirt poor. The poorest is Gordon Retreat, a dead-end mud road three blocks past the firehouse. Two-room houses, falling down, porches filled with old women and flowers. A long-armed girl stops jumping rope in the road when she sees the car. She stands, as still as the sun, and watches. The rope rests in her hair.

The address is on the right, halfway to the end. An old man sits on the porch in front of a television set, eating watermelon with a pocket knife, watching soap operas. Inside an old woman is dying of cancer.

She is on a hospital bed in the front room, staring at the ceiling. Her arms are as thin as the rails that keep her from falling into the night. There is a fan in the corner, the room is still hot. But it is her room, it is her home, her island. She has almost lived her life here now, and she would not move and have it finished somewhere else.

The old woman struggles up to shake hands, then drops back into her pillow. “Simple things,” she says. She catches her breath. A line of sweat shines on the bones of her chest, then tears and runs off into her nightclothes. From where she lies, she can look up and see the wall behind her. There is a picture there, freshly dusted, of a football player.

The football player is Jim Brown, the woman is his last connection with the white sands and a time when there was no question he belonged. The woman is his grandmother.

The house sits in the mountains over Hollywood, a couple of hundred feet off Sunset Plaza Drive. It’s a clear day and from the living room you can look out over the swimming pool and see Los Angeles County all the way to the ocean. At night, the lights could be your carpet.

“The house is worth a million-two, a million-four; and there’s the view and the pool and all that, but that’s not why he lives there. It’s the privacy.”

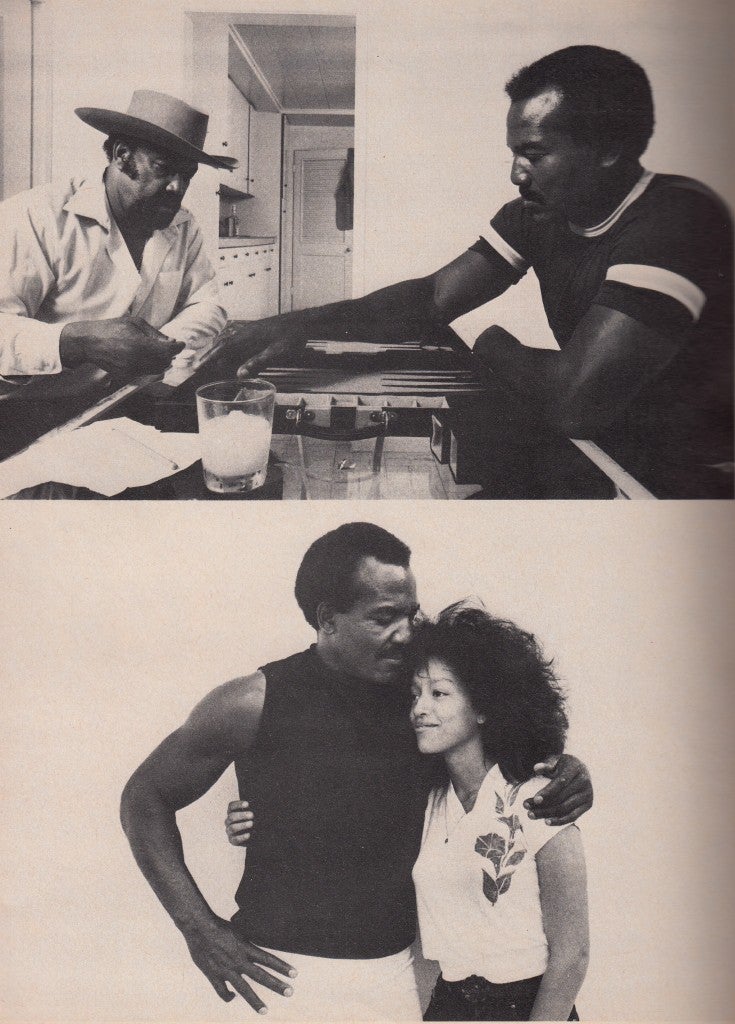

The man who said that is George Hughley, who is in the room off the kitchen with Brown now, playing backgammon. They play a loud game—a lot of standing up and shouting. The birds have left the tree outside the window until it’s over. Hughley was a fullback, too, a couple of years in Canada and one season with the Redskins. He is one of a handful of people Brown allows in close. “With George,” he says, “you don’t have to be more than you are.” There is Hughley and Bill Russell and maybe the girl who lives with him.

Her name is Kim, he met her at a roller-skating rink. She is 19 or 20, so pretty you could just stick a fork in your leg. She comes out of the bedroom to answer the phone with a pencil in her mouth, wearing Brown’s slippers and carrying an open book. The phone rings every five minutes. It is always for Brown.

“Whatever I’m here for, 80,000 people cheerin’ because I just scored a touchdown isn’t it.”

“You’ve been around long enough to see that people come by all the time,” George said later. “They come and go—only a few matter to him—but it gives him the chance to choose who he’s around. As long as he lives, he’s going to be Jim Brown, the football player. He went to a place in human activity where he was all alone, where no one else was, and he’s one of the few human beings to achieve that singular status who didn’t insulate himself with flunkies. Up here, he’s got some control over who he sees.”

And they come by all the time, these people who don’t matter.

Just now, though, it’s only George and Jim and the backgammon board. They are playing for $50. A mason jar filled with vodka and apple juice is next to Brown on the table. George drinks from a glass, and he is winning. You can tell because he is making most of the noise. When the game turns, Brown does the talking.

George rolls the dice. “I’m the lawn mower now,” he says, “and your ass is the grass.”

“Where is it?” Brown says. “Where is your move?”

“Where you think it is, turkey butt?” George moves. “I don’t hear you now, do I?”

“I’m watchin’ your chubby-ass hand, Rufus.”

“I don’t care what you watch. Gammon….”

Brown takes the gammon, doubling the stakes. He rolls. George rolls. They accuse each other of rolling too fast, then too slow.

Brown looks across the table. George says, “C’mon, man, move.”

Brown says, “Go slow, Negro.”

They play for two hours and then, toward the end, in the middle of all the shouting and insults, something changes. George rolls before Brown has finished his moves—they have both done it 20 times—but this time Brown makes him take it over. George argues but finally gives in. The new roll beats him.

“Who was wrong?” Brown says.

George argues, points. Brown sits still, asking, “Who was wrong?” over and over.

And George gives in again. “I was wrong.”

Brown nods, it relaxes. It seems like a strange thing to want from a friend.

They play out the game and then George writes a check. The house is suddenly quiet, the birds come back to the tree outside the window.

Brown makes a new drink and sits down at the table. No matter how much he drinks, it never shows. “You got scared, George,” he says. “When you’re scared you don’t get nothin’. From the dice or nothin’ else.”

“Scared of what? Fifty dollars?”

“You went blind in your anxiety.” Brown is preoccupied with why people lose; it means as much as the winning or losing itself. A couple of days later, playing golf with Bill Russell, he will watch a man in the foursome ahead top a wood off the tee. The ball skips into some trees and the man screams and throws the club after it. Brown smiles. “I always wonder about those cats,” he says.

“Is that the first time that’s happened? I mean, is he surprised? The man’s a 22 handicap, how did he get to be a 22?”

Now he says to George, “Anything you do, if you lose, don’t let it be because you give it up.”

Later, George says, “People who don’t know us, they think somebody is about to die on the kitchen table. Of course, that what it sounds like, but it’s also Jim’s reputation. Smoldering violence. People want to believe that he won’t argue with them. He isn’t going to sit around explaining himself.

“The simple truth is, he’s an emotional person. He’s up and down, but he doesn’t put it out there for everybody to see. Sure, he gets happy. Just because you don’t see it doesn’t mean it isn’t happening inside.”

I ask him to remember a time. “When Richard [Pryor] was in the hospital,” he says. (Pryor was burned almost to death last year.) “Jim was over there every day, all afternoon, and when Richard started to get better and Jim saw he was making a difference, that touched him.

“I’d see him evenings. He never said it, but he was happy. He was doing something, there were no strings attached….”

“Let me tell you a story,” she says, “about when Jim and I were married. Jimmy, the baby, was two years old and he had chronic tonsillitis. I took him to the hospital, and on the way over there I stopped and bought him a little football. He looked at it and began askin’ for his daddy.

“I called Jim from the hospital and said the baby was askin’ for him. He said he’d be by. Every day I told him, every day he said he’d come by. And he never did. It wasn’t a deliberate thing, he just couldn’t deal with weakness. Hospitals, sickness, death.

“If he found a flaw in you, he’d press on it and press on it. I don’t know if it was trying to point something out, or if it just came naturally to him to do that. When he found people in a way where they couldn’t help themselves, though, he just removed himself from the premises.”

Sue Brown was married to Jim Brown for 10 years and they had three children. She lives in Atlanta now, in an apartment filled with mirrors and glass, and sells a line of lingerie to suburban housewives rediscovering their sexuality. They have selling parties in their homes and you read about them in the style section of your newspaper.

She comes downstairs wrapped in purple, a shoulder in, a shoulder out, wearing what look like glass slippers. At first I mistake her for her daughter, Kim, who is 21. A dog the size of a sparrow follows her down, biting at her feet.

“When I met Jim, he’d just been named rookie of the year,” she says. “I was just a country girl from Columbus, Georgia. I always thought that was one of the reasons he married me—I was a country girl, somebody he didn’t have to bother with.

“Before we got married he said there was always going to be other women. He said, ‘You’re never going to have a little picket fence. I’m Jim Brown, I can marry anybody in the world, and there are always going to be other women. Can you deal with that?’

“I said I could, and I did. I knew about the paternity suit before it was filed. I knew about everything. Jim never lied. I respect that. He’d hurt you, but he’d always tell the truth.

“He was the most popular man in Cleveland. He could have been mayor, and he was always out on the street where they loved him. He was possessive of his attention. I remember once he decided to buy the children bicycles. He said, ‘C’mon, let’s go,’ but Kim wanted to stay with me. That made Jim mad. To him it meant she liked me better than him, and he said, ‘You don’t have to come, but I’m not bringin’ bicycles for anybody who stays home’

“She stayed with me, and he and the boys came back later with only two bikes. Another time he cut her allowance. He’d give this one 25, this one 25, and this one 10. I said, ‘You can’t do that, it’s discrimination.’ He said no it wasn’t. He was just going to pay the most to the ones who liked him best.”

Brown is sitting on the couch in his living room. The record player is on and Blondie is piped into most of the rooms in the house. The record player is always on.

The sun has gone down. Kim brings him a plate of tuna fish covered with something green and yellow and wet that could be Mexican.

He eats it on salad, too.

“Money is lonely anyway. When you got it, people always want it. You don’t want to be used, sometimes you don’t know where a cat is comin’ from. Money is lonely, but it’s a bitch not to have it.”

“Young girls, they touch you,” he says. “They say what they feel, they do their choosin’ from the soul. You come home and pull off your shoes, and she loves you that way, too.” He thinks about it. “I like tight bodies and pretty faces. You bring in Methuselah, if she’s got a tight body and a pretty face, that’s all right, too.

“I tell all of them, though, nature’s got a plan. There’s a pretty girl turning 16 years old every day. It’s none of this takin’ advantage thing. Marlon Brando said it once, ‘I don’t want my bitch pushin’ me around in my wheelchair.’ I feel like that, too.

“It’s not forever. When it’s up, it’s up. And when I cut a lady loose, she’s takin’ something away. She’s going away knowin’ how to deal better. I show her that and maybe it makes her stronger the rest of her life.”

He finishes the tuna fish and Kim comes and takes the plate. It’s all he will eat for supper. “If I couldn’t have discipline,” he says, “if I sit up eatin’ fried chicken in bed at night, I’d just as soon be dead. I take care of myself. If you’re an old cat around young girls, you got to have somethin’ to bring to the table.”

He sits back and the muscles flatten under his shirt. Six-two and 230 pounds, he is the size he was when he played and there is only the gray hair on his chest to make you think he couldn’t put on a uniform tomorrow and pick it all back up where he left it.

It’s been 15 years, though.

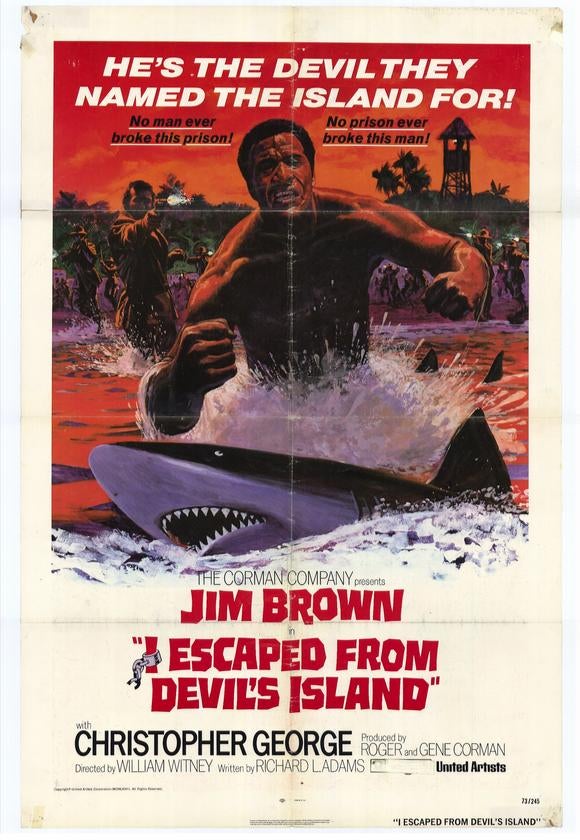

And six years since Take a Hard Ride, his last major picture. “That long?” he says. “Really, man, I don’t keep track. I don’t think in terms like that. I don’t look back.”

There is a lot to look back on, a lot of time to do it. His business now is trying to put together the financing to distribute a film he produced. He’d called it Do They Ever Cry in America? but the money men already have changed that to Pacific Inferno.

“I don’t necessarily take being out of work personally,” he says. “Somebody doesn’t like me or I’d be gettin’ parts, but then, who’s making movies now? I mean blacks. You got Richard [Pryor] and that’s it. I don’t know why, but it probably has something to do with all those super fly movies. They put a cold black dude in there, shootin’ people, and everybody wanted to see it. So they did it again, over and over, until nobody wanted to see it, the same way you ruin the earth if you keep plantin’ the same crop.

“When it was used up, they blamed the actors and actresses, and now nobody’s working.”

George Hughley had said something else about it. “There’s a lot of posing and ass-kissing that goes down in that business. If he’d done some of that, he might be working more. Of course, if he’d done some of that he wouldn’t be who he is.”

Brown says, “If you kiss somebody’s ass for $100,000, the $100,000 can go pretty fast, but 10 years down the road you still kissed the ass. It all comes around.

“Money is lonely anyway. When you got it, people always want it. You don’t want to be used, sometimes you don’t know where a cat is comin’ from. Money is lonely, but it’s a bitch not to have it.”

You think of the house in Gordon Retreat, the old lady dying in the living room, and all the ways not having it can look.

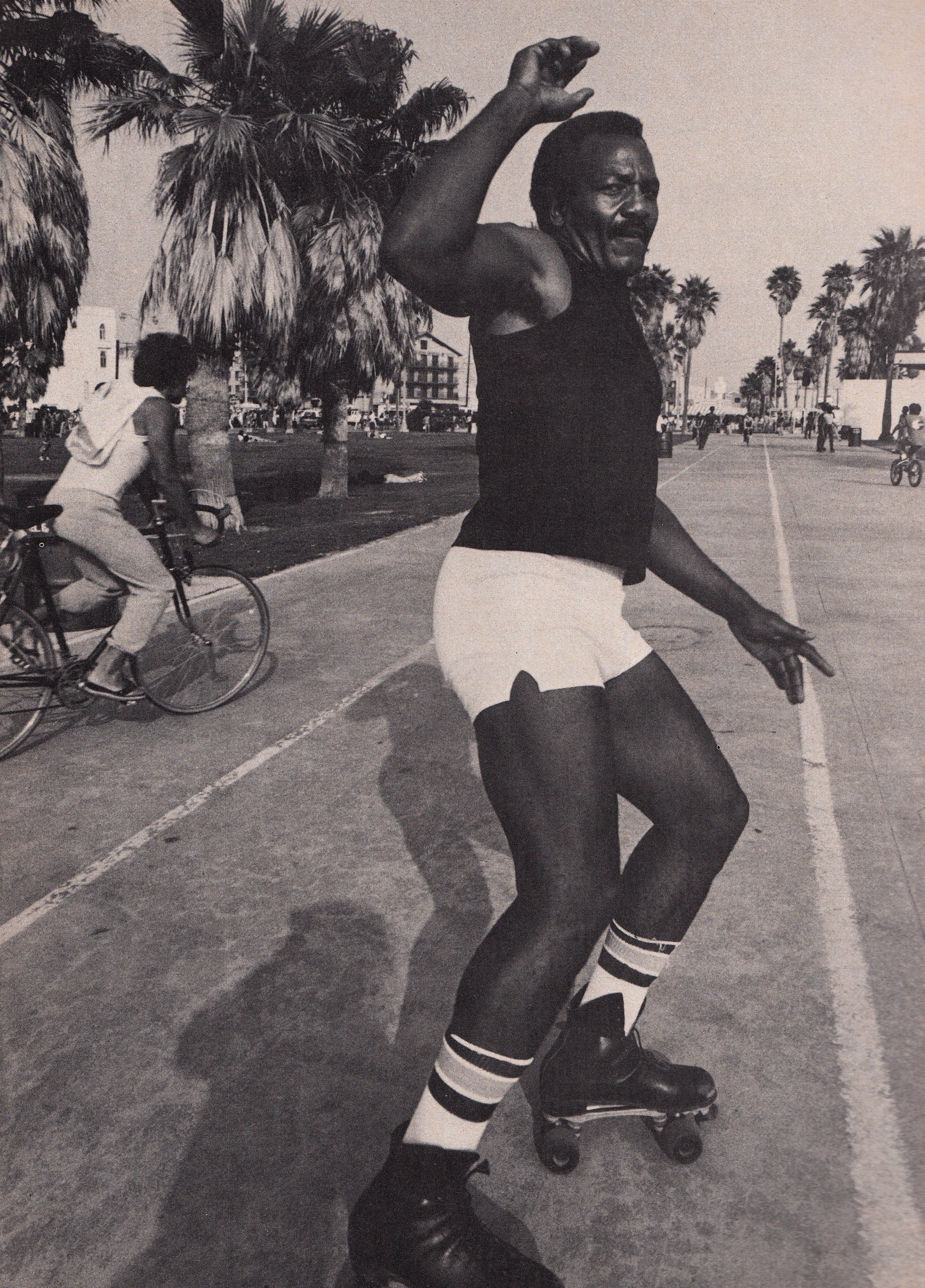

“The trick,” he says, “is waking up in the morning, lookin’ in the mirror and knowing you could be broke in two months, and not gettin’ messed up about it. Yeah, that could happen in two months. I’m not going to cry about it. I can move somewhere else, be a hermit. I don’t have to live on a mountain in L.A. I don’t have to go to clubs and play golf and tennis, belong to skating rinks.”

A few minutes later he gets up to go roller skating. Kim stays home to study. She follows him to the door, still in his slippers. Brown checks the lock before he goes out.

“Don’t let anybody in but George,” he says.

Jim Brown was left as an infant with his great-grandmother after his father, Swinton “Sweet Sue” Brown—a come-and-go gambler and club fighter—deserted his mother and she went to New York to work as a maid.

After the great-grandmother died, his mother brought Jim to Manhasset, Long Island. He was nine years old. They lived in the house where she worked. He had good clothes; he went to school in a cab. The man who owned the house built a backboard for him in the driveway.

His mother worked and saved at one purpose: to move out, into a house of her own.

Years later, when Brown was the highest-paid player in football, he publicly would refer to himself as a “nigger.” He would refuse to go to team parties. “They’d have one party for everybody, then one for just the whites,” he said. “You can’t ask me to come to your house, then say I can only hang in the kitchen. If I’ve got to be a nigger, I still don’t have to be a house nigger.”

His football coach at Manhasset High School was Ed Walsh. “There is simply a good human being,” Brown said. “It doesn’t have anything to do with football. He offered to let me live in his house. One cat like that can screw up all your theories about white people.

“Eventually, of course, if you pay attention you see that blackness can’t give you nothin’. Nothing good ever came out of being any race, it’s all negative. You got a bunch of cats now thinkin’ it’s just whitey. You don’t think they got problems in Africa? Over there it’s not what color, it’s what tribe. You’re from the wrong tribe, somebody from another tribe’s going to try to kill your ass for it. You ought to be aware of it. You don’t have to do nothin’ about it, just know it’s there.”

Forty-two colleges offered Brown scholarships out of high school. He picked Syracuse where some of the coaches tried to make him a tackle. “I think there was a resistance to trusting the old pill to a Negro,” he said.

In one year Brown went from fifth string to All-American. He was also an All-American in lacrosse, close to it in track, and played varsity basketball. He was the best amateur athlete in the country and in 1957, his first year with the Cleveland Browns, he became, arguably, the best professional athlete in the country.

“From the beginning, I saw they liked black players who didn’t talk, so I didn’t talk. I gave myself to them physically, never drank or smoked, all the clean-living stuff you were supposed to do. As I became a star, they wanted more. They wanted me to endorse the system. Again, I am not a house nigger.

“Paul [Brown] had an offense built around me running the ball. He didn’t like to pass. The rest of the league had moved to a balanced game, but there was no bend in him at all. The Browns believed I couldn’t be hurt, at least not bad enough not to play, just like everybody else believed. It was that old game, people takin’ the best of your ass and leavin’ the rest.”

For nine years, Brown was all alone on top of professional football, by choice and by talent. He played like a storm front rolling in over a Kansas farmhouse, with thunder and lulls, a sudden chill before the damage.

In 1962, Brown led a players’ revolt that ended in Paul Brown’s removal.

In 1963, he had the finest season any running back has had, before or since. His 12 touchdowns and 1,863 yards don’t match O.J. Simpson’s great year, but the game was different then. At the time Brown came into the league, five running backs had run for 1,000 yards in a season. The year Simpson went over 2,000, 1973, there were four others over 1,000. The year before that, there were 10.

In nine years with Cleveland, Jim Brown led the league in rushing eight times. He scored 126 touchdowns, gained 12,312 yards.

“Physically,” Brown says, “there was only a hair of difference between me and the other running backs. I never laid back and relied on natural ability. The real difference was that I could focus, I could rise up. I kept within myself so there always would be something there to use.”

For nine years, Brown was all alone on top of professional football, by choice and by talent. He played like a storm front rolling in over a Kansas farmhouse, with thunder and lulls, a sudden chill before the damage. Inevitable. He came one way, from all directions, and all there was for it was to tie down what you could and hope he didn’t take the roof. “He wasn’t out there to hurt you, but it would happen.” Sam Huff thinks he remembers every play. “He was the most dangerous when you thought you had him. He’d gather himself up and leave you.”

It ended in 1966, in England.

The Dirty Dozen was three weeks behind schedule. It was late June and Brown had signed a contract committing himself to stay on the set until shooting was finished. With the rain delays, this meant he would be spending the Browns’ exhibition season on the playing fields of Beechwood Park School for Boys, just outside London.

He hadn’t told the Browns that yet. Maybe he hadn’t decided for himself what he would do.

While the actors waited out the delays and schedule problems, some played catch with a football. One afternoon, one of them noticed Brown standing alone on the sidelines and threw him the ball. Brown stood still and cold—nothing moving even in his face—and let it bounce off his chest. “Only for money,” he said.

Three weeks later, when the reporters came in for the announcement, Brown was playing touch football with Lee Marvin and John Cassavetes. He seemed relaxed. The Browns had heard of the movie contract and forced the issue, and the National Football League had lost its greatest player.

“I still watch on television,” he says. “Sometimes we’ll talk about this guy or that guy, who was better, me or Earl [Campbell], me or O.J., but, you know, whatever I’m here for, 80,000 people cheerin’ because I just scored a touchdown isn’t it.”

That night Brown goes roller skating in Venice. He drives over in a 1969 Mercedes convertible that he has had since it was a month old. It is priceless, but like all priceless things in this world its voltage regulator doesn’t work. The week before, the warning light had come on and Brown had pulled into a dealership and skated to the ocean and back while they tried to fix it. Seven miles each way.

As he drives, he watches the light glowing on the dashboard and explains Doctor Zhivago to a kid he skates with. “You see, there were three dudes and two chicks,” he says. “One chick was sweet, one knew it all. One of the cats was a little too far out. One was knowledgeable and one of them was just in love.”

The kid says, “Did the young dude get the chick?”

Brown begins to smile. “Rod Steiger,” he says. “Rod Steiger got into her quilt.”

That brings the kid up short. “That’s all right, man,” Brown says. “Just sometimes the old cat wins.”

There are two or three hundred people at the skating rink. Kids, people who want to be kids.

Brown is dressed all in black. He seems to skate without effort and it surprises you when he comes off the floor washed in sweat. He goes on and off the floor for two hours. He meets girls, he drinks vodka and apple juice from his mason jar. It never shows.

A week before, a 20- or 21-year-old girl had talked to him about 10 minutes and suddenly said, “I’d like to go with you tonight, but if your thing is, you know, beating up women….” He had laughed.

“People meet me,” he’d said later, “they don’t know what’s goin’ on. They’re always waitin’ for me to jump up and down and kick somebody’s ass.”

Twenty minutes to closing time some of the lights go out, and the ones that are left make a circle on the middle of the floor. The music stops and the disc jockey makes an announcement:

“And now, in the middle of the floor, Mr. Jimmy Brown….”

The music starts again. Brown skates alone in a slow, wide circle. A girl falls in behind him, holding on to his waist. A kid grabs her, another girl grabs him. In five minutes 70 people are attached to Brown, all trying to push off the same skate at the same time as Jim Brown.

The circle gets tighter, the end becomes a whip. Kids drop off in threes and fours. Brown looks straight ahead. A kid falls, the spot becomes a pile of bodies. Finally the tug from behind is too much for the girl attached to Brown. She lets go and falls, and he is by himself again. He slows and waits for the others to catch up, but he never looks back.

As long as the music lasts, he never looks back.

In a period of three months in 1965, Brown was accused of beating and sexually molesting two teenage girls. One dropped the charges, the other one went to court and lost. She filed a paternity suit then and lost that, too.

People who know Brown say that if he had done what she said, he wouldn’t have gone to court and lied. “There’s been lies written about me,” he says, “there’s been some truth, too. I’m no angel, but what I do, I tell the truth about.”

Jim Brown scares people and he controls them. The relationships he has—family, friends, women, strangers in the street—are on his own terms.

In June of 1968, he was arrested and charged with assault with intent to commit murder when his girlfriend, a 22-year-old model named Eva Bohn-Chin, was found semi-conscious beneath the balcony of his Hollywood apartment. The neighbors had heard an argument and called the police.

He also was charged with felony battery on a peace officer and obstructing justice. “The police is just another cat,” he said. The first sheriff’s deputy who came through the front door that day also went through the closet door.

“Listen,” he said, “you got to have something, goin’ out dealing with 270-pound linemen for a living. You quit playing, but that doesn’t just go away.”

The charge of assault with intent to commit murder was dropped when Eva Bohn-Chin told police she had fallen trying to get out when they showed up.

The charges by the cop were changed to resisting a deputy. Brown was fined $300 and that marked the beginning of his problems with the Los Angeles Sheriff’s Department.

“Those suckers knew a little about my head,” he said, “and they waited for me to do something so they could shoot me. For two months they came by most every night to tell me to turn down my music.

“They were lookin’ for me once—I think it was about that fat cat I pulled off my car at the golf course.” (Brown was charged with felonious assault after a minor traffic accident in which a man fixed himself on Brown’s hood and wouldn’t move until Brown picked him off. Bill Russell had been along that day. “The guy was 270 at least,” Russell said, “you could tell he wasn’t used to gettin’ picked up.” The charges were thrown out of court.) “Anyway, my lawyer called to say he’d set it up for me to come down and surrender in the morning.

“That’s cool. Not great, but it had to be done. Then that same night the cops stopped me on the way home, pulled me out of my car to take me in. There were two or three police cars, all those cops waitin’ for me to explode. I didn’t say a word. If you lose, don’t let it be because you gave it up, try not to help the enemy kill your ass.”

In August 1969, Brown publicly accused the Sheriff’s Department of harassment and “grossly distorted factual representations” of his problems with the law.

The accusation—along with the fact that for as many times as he’d been arrested, the only thing Brown had been convicted of was resisting the deputy—led to a meeting with Sheriff Peter Pitchess. Brown’s feeling was that at least part of his trouble with the Sheriff’s Department was racial.

They met out of the city, at Chuck Connors’s house in Palm Springs, and made a kind of peace.

The sheriff got there first. He’d come with a deputy. Brown walked in with the prettiest little 15-year-old blonde he could find.

Sheriff Pitchess declined to comment on his association with Brown. Others have moved, gotten married, disappeared. It’s been a long time. It is a fact, though, that an athlete as visible as Jim Brown is vulnerable to paternity suits and accusations of assault.

It is also a fact that Jim Brown scares people. He scares people, and he controls them. The relationships he has—family, friends, women, strangers in the street—are on his own terms. When he says he won’t lie and he won’t change, that is his integrity and it doesn’t shift with the situation.

When the critics talked about his presence on the screen, they were talking about that control, that fear. The longer pieces written about him are full of that, and flawed by it. Some of the people who knew him are reluctant to talk about him now. A writer said, “Jim and I are all right now. I wouldn’t want my name in anything about him.” His mother said, “He’s the only one I got. Things are right between us now and I wouldn’t say nothin’ to upset that.”

“I ain’t going to let anybody make me think I’m a monster. I know what I feel like inside.”

And there are others—a coach, an old girlfriend’s mother—who carry an affection for him that time hasn’t touched.

There’s one more thing, too. His wife put it this way: “Everybody’s afraid of that black side of his temper, but who’s ever seen it? He doesn’t go givin’ himself away in public.”

“When I left him,” she said, “he was on location, making a movie. I wrote him a letter because I was afraid of his temper. I mailed it and waited for the explosion, and for months after that I didn’t hear a word.

“I’d left him before, taken the babies home to my mother’s—but that was always to hurt him and it did. He wanted his family. But when I divorced him it wasn’t his temper or the mood changes. It wasn’t other women.

“He wanted to own us, but he spent his time on the street, with strangers. You know, there was a distance with them. He didn’t have time to take us to the grocery store or church. He’d say, ‘Here’s the money. Buy anything you need.’

“He kept us away from the press—he had me take the kids out of town when there was public trouble, like a paternity suit. He never wanted me to work or do anything on my own. When we were out in public, we were always hugged up. At home, he was someplace you couldn’t touch.

“Of course, we had our precious moments. Like, he sent me a basket of fruit from Florida, or I might walk outside and see a new car. It wouldn’t ever be because it was Christmas, it would be because he felt like buying me a car. He never remembered Christmas or birthdays, even with the kids. He’d say ‘If I don’t know when your birthday is or how old you are, so what? Let’s get us a relationship here.’ It was more like he wanted them for friends.”

Sue Brown leaned closer and almost whispered. “Listen,” she said. “Jim is not a normal person. The dentist couldn’t numb this man’s gums. He could drink champagne—bottles of it—and never get drunk. It never fazed him. He played football with broken ribs and some nights he’d come home and I’d have to take his clothes off for him. Some nights I’d bathe him. But he could play like that. I never knew how.

“I want to tell you something else. There is a gentle side, too. The day the headlines broke that he was being charged with attempting to murder Eva, I knew he didn’t do it. I thought maybe he hit her—he has that temper—but I knew Jim wouldn’t try to kill any woman.

“There’s things in him that nobody will ever understand, but it isn’t that he’s mean. He’s just who he is.”

Sue Brown shrugs. “It wasn’t easy. You never understand him, but you learn to cope and you respect him. Jim Brown took me out of Columbia, Georgia, he taught me to be strong and I’ll always be grateful for that.”

A week of days, a week of nights. He is always in motion. He plays golf or tennis and the games are the same. Contained, rushed, terrible-looking swings with all the power coming from his arms and shoulders. He plays spin and position and somehow wills the ball to go where he wants it. And in the end, he wins.

Afterward he will drop $220 at backgammon or win $100 playing chess. He goes roller skating and nightclubbing. He runs up the mountain with Kim. He makes phone calls, trying to put the money together for Pacific Inferno.

“He’d rather be workin’,” his friend George Hughley said, “and maybe some of what he does is to keep his mind off it. He handles it though. He won’t borrow, he won’t compromise, he doesn’t explain himself….”

Everywhere outside, people watch. At home he brings them in. He doesn’t seem to notice them, but he does. Jim Brown sees everything around him. They don’t seem to matter to him, but they are always there.

On this night, 40 people will show up to be in his living room. “They come through all the time, sayin’ how much they like me,” he says. “Well, I don’t want a cat to say he likes me if he doesn’t know me. I want him to say he doesn’t know me.”

He has showered and dressed. Kim walks through the room without a sound, looking 16. I don’t mean to insult her, but I ask whom he goes to when he feels like crying.

He smiles at me and turns it around. “What, you got one of those liberated marriages?” And a few minutes later, “Anybody messes with my woman has a fight. Maybe they’ll win it, but it’s out there in front of them. I won’t have nobody makin’ a public spectacle of my ass.”

He stands up and finds his car keys. There are errands to run before the people come. “I haven’t changed,” he says. “I ain’t going to let anybody make me think I’m a monster. I know what I feel like inside.”

In the 10 years after he quit football, Jim Brown made 17 movies. There has been one since. In that time he became a competent actor, but as a football player he was the one they measured the others against.

He spent two seasons on CBS as a color man for NFL football, teamed with George Allen and Vin Scully—a job he cared for more than acting. “I knew I had something to offer there,” he said. He doesn’t know why he was taken off and he hasn’t asked.

At one time or another, Brown has owned or controlled half a dozen businesses. Some made it, some failed. Brown left them all.

He founded—and threw huge amounts of money after—the Black Economic Union he set up to put blacks into business ownership. It has gone one way, Brown another.

He sees his kids occasionally—the oldest son lives in Southern California and Jim Brown Jr. plays basketball for USC—but when he talks about his family, it is something from a long time ago.

And the signs are that the life on the mountain in Los Angeles is on the way out, too.

He says, “You know, it’s possible to go out with style. When I cross the line, it’s going to be with some dignity, not screamin’, trying to hold on. You can’t hold on to nothin’ forever. A woman, a house, even your life, and if you’re afraid, it only makes you weak.”

And when the time comes, he’ll leave Hollywood for someplace else, maybe someplace with hard-sand beaches to walk, where people can watch him from a distance and know him on certain terms. And what those terms are, Jim Brown will control. Mostly they won’t know him at all.

A few of these people will get closer than the rest, and the ones who know him best—the ones who love him—won’t blame him if he can’t love them back.

You don’t blame a lion for being a lion.

He checks the lock on the door before he goes out and tells Kim he will be about an hour. “Don’t let anybody in but George,” he says.

[Photos by Barbra Walz via Inside Sports]