He came straight from Florida, and in black tie the combination of the tan and the tux glistened in the heat of the night. His eyes were bright, gorgeous green, and the shadings of brown in his hair were caught, then polished by the spotlight that seemed to underline his every step. It was an awards dinner for his friend and mentor, Sonny Werblin, and as such there were many celebrated athletes in attendance. But none had his star. None approached his luster. He was the last to arrive, and the minute he walked in the room you could tell he was a man of distinction.

“Go tell daddy, it’s Joe Namath.”

They came at him in waves, getting closer and closer, until they surrounded him, making him a gem in a portable setting. They thrust paper and pen at him, and as he signed his name and his best wishes he smiled easily, warmly, as if his only purpose was to give pleasure, his only goal to give comfort.

“Kevin. How are you?”

“Lorraine, you’re beautiful.”

“Mary. Mary!”

Mary. No more than seven or eight. He reached for her hand.

“Mary? May I?”

As the flashcubes popped he bent down and kissed her cheek. Because his kiss was on their list as the best thing in life.

“Forget the signature, I want the kiss; somebody get a picture.”

Radiant, smooth, thoroughly approachable. Never signing his name without first asking yours. Walking the fine line between a son and a lover and making it a highway. Men came away saying he was looking better than ever, and not begrudging him; women came away floating, as if in a satin-and-chiffon fantasy.

She was in her early 30s. Not a beauty but doing the best she could. If she’d thought about it, she’d never have done it—but sometimes you just don’t think. She held up her car keys and waved them at him.

“I’ll catch you later, okay Joe?”

As tan as it was, Joe Namath’s face still had room for red.

It was her husband who spoke next.

“As long as you get her back early, all right Joe?” The husband was laughing.

Joe Namath still had the magic, the sexuality embracing men and women but threatening neither; the sexuality that warmed but didn’t burn. The gift.

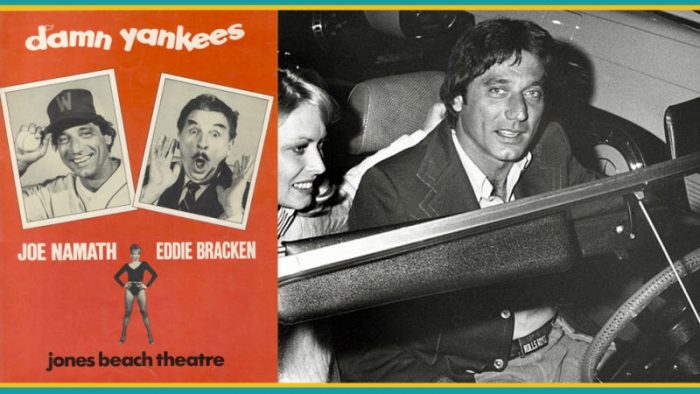

Richard Horner, the producer at the Jones Beach Theatre on Long Island, needed a musical to fill his 10 weeks of summer dates, and the more he noticed how “sports figures are very much in the news these days,” the more he thought about Damn Yankees. But who would play Joe Hardy—Shoeless Joe from Hannibal, Mo.—the man who sells his soul to the devil just to beat those damn Yankees?

In for a dime, in for a dollar. “If you’re going to do a show on sports on Long Island,” Horner said to himself, “what about Joe Namath? He’s still a hero out there.” Horner had seen Namath’s commercials, and he knew Namath had done summer stock as Li’l Abner the year before, so he called his friend who had directed the show, Ed Greenberg, and got this scouting report on Namath: Sang well, acted well; one hell of a cooperative fellow. Horner called Namath, sent him a print of the movie version and, without having met him, signed Namath for $15,000 a week.

And now Horner was talking about his bold move, about taking a chance on a former quarterback with white shoes, bad knees and gorgeous green eyes, and Horner said, “Some of the people in my office said to me, ‘Jesus, why Namath?’ And I said, ‘I think people want to see him. He has charisma.’”

At 21, a star. At 25, a legend. At 38, a question: Is what he was more than what he is?

It is 8:30 in the morning, 90 minutes before his call for the first day of rehearsal for Damn Yankees. In less than one month Joe Namath will make his New York metropolitan-area theatrical debut, and he is looking forward to it. Granted, his acting career has not yet healed the sick, raised the dead and made the little girls talk out of their heads. None of his previous films had made him a star, and his television series, The Waverly Wonders, lasted three weeks, a Kohoutek if ever there was one. Summer stock in Jones Beach may, in fact, be the Carolina League of show business, but as Dave Herman, Namath’s former teammate on the Super Bowl champion Jets of 1969, says, “I guarantee you one thing. He’s not doing this because it’s expected of him; Joe does everything because he wants to.”

“I have so much respect for him,” says John Dockery, a former teammate and still a business partner. “I say to him, ‘I can’t believe the risks you take, singing and dancing onstage.’ I’m flabbergasted. But Joe’s a gambler; he takes his chances.”

The word “gambler” has disturbed him.

“I’m not a gambler,” Namath says.

Gilt by association: “Joe lit up a room then like he light it up now,” says Sonny Werblin.

Gambler. A bad word. A pejorative context. The memory of Bachelors III, Pete Rozelle and the showdown perhaps not so hazy after all these years.

“I don’t take risks that I don’t think I can come through with,” he says. “I know I’m a much better actor now than I was three years ago…. Sure, this project might seem like a crossroads. If I don’t do a good job, there’ll be plenty of people who’ll say, ‘Can’t use him.’ But if I do a good job, that many more people will want to work with me…. I wouldn’t be doing Damn Yankees if my voice coach didn’t think I could handle it, and I know I can handle the acting.”

Being onstage makes Namath nervous, but it doesn’t scare him. He’s used to it; he’s been on center stage since he was a quarterback at Alabama. (What was it Namath said about beating the Colts? “I guarantee it.” Of course.) He has even told some fellow actors that he would rather be onstage than in motion pictures or on television.

Broadway, Joe?

“Oh, yeah,” he says, his gorgeous green eyes bright enough to laser beam the sheets.

And then serious. This isn’t vaudeville. He isn’t Jake LaMotta. “But I don’t want to be there as the ex-football player; I want to be there as the actor.”

Conversations with Joe, Part I

“Don Maynard, the first day I showed up in the Jet locker room, told me, ‘Joe, you got to be able to do the job; the first day you can’t do the job they get rid of you. So make sure there’s something else you can do.’ Ever since my first day—and Mr. Werblin was part of this—we were preparing for the day football was over, preparing to find a worthwhile profession. I know sports isn’t everything. Football isn’t necessary. Baseball? I don’t give a damn if there’s a strike. So what? The world’s going to stop? There’s more important things than sports, and if the right people teach you this, the day the end comes, it isn’t a surprise….

“Dr. Nichols, after my first knee operation, he was happy. He told me everything went well and I had four years; he said if I played four years then the Jets would be happy. I was elated, because there were some doubts I could play at all and here he said I had four years. Well, I ended up playing 13 years, which was great, but we won the Super Bowl in my fourth year. Now, I don’t know if there was such an intense drive to get it done in four years—but there was a lot of intensity; there was an understanding I might not be able to work very long. Lying in the hospital, having the doctor tell you, you have four years. Hell, I was still in college. I was 21, 22 years old then—I knew I had to do something else down the road.”

Travels with Joe, Part I

Lunch break on the first day of rehearsal for Damn Yankees. Namath, his Alabama buddy, Hoot Owl Hicks, and his road manager, Wayne Little, scrunch into a booth at a coffee shop. Dottie, the waitress, is taking their order when she suddenly realizes that the man asking for a turkey sandwich and a shrimp platter is not just anybody. She does a professional double take, worthy of Alice at Mel’s Diner.

“Joey!” she screams, and she gives him a kiss.

“If he did it all again now, Joe would not rise to the same heights,” says Dockery. “The antihero is passé now; Joe came at the time he was destined to come.”

The buzz in the coffee shop sounds like a day of the locusts. People come up to Namath and ask for autographs. The owner, a small woman with nursing-home gray hair takes hummingbird steps to the table and says, “You’re causing quite a commotion.” Before Namath can apologize she shhhushes him. “Don’t worry,” she says. “It’s good for business.”

The last man is fat and 40. He carries three pictures for Namath to sign, including one of Namath and Ann-Margret on the set of C.C. and Company, Namath’s first starring vehicle. Namath cannot believe anyone would care so much to save these pictures. On the way out the man calls to him, “Joe, by the way, thanks for beating the Colts,” and pats his wallet.

Even before Super Bowl III, Namath was the hottest athlete in the nation. After it he was at 3,000 degrees, he was a core melt-down. The late ’60s and the early ’70s were times of compelling social and political upheaval, and Namath, with his antiestablishment shaggy hair, mustache, white shoes and his Life-Is-a-Bacchanal philosophy, became a symbol of inevitable, triumphant change. The antihero.

“If he did it all again now, Joe would not rise to the same heights,” says Dockery. “The antihero is passé now; Joe came at the time he was destined to come.”

Anyone could have read the scouting reports, but what David A. (Sonny, as in Money) Werblin saw was someone who jumped off the screen. Werblin saw Star Quality, and as owner of the AFL Jets he nursed it, rehearsed it and gave out the news. “Joe lit up a room then like he lights it up now,” Werblin says. And in Namath, Werblin, the star maker, found his leading man.

The moments were golden.

Gilt by association.

“It was like traveling with a Beatle,” says Jim Hudson, who roomed with Namath. “We’d check into a hotel and take the phone off the hook or it’d be ringing all the time. We couldn’t eat at normal times because so many people wanted Joe’s autograph. That’s why Joe started eating dinner at midnight—just to get a little peace and quiet.”

Whenever the Jets went on the road they had to devise secret ways to get Namath in and out of the stadium. Once they shuttled him out in an armored Brinks truck. Sometimes he left in a laundry cart, buried under dirty jocks and socks. In San Diego he was taken away in an equipment truck and the team bus picked him up on the freeway, two miles away from the stadium.

“I’d never been around somebody as famous as that, and I was really enamored of it when I was a rookie,” says Steve Tannen, a former teammate on the Jets. “There was always an entourage around—you know, Guido, Vito, guys like that. Joe and I got tight, and some people even started calling me ‘Subway Steve.’ But I didn’t want to become just one of Joe’s people. I thought he felt more comfortable with people who were somewhat subservient to him; I don’t know that he planned it that way, but it was part of the package.”

And yes, there were always women.

“Women were never a problem,” says Tannen. “Not that it was territory indigenous to Joe; a lot of athletes have women. But we would be sitting in Bachelors III, and when it came time to go, Joe would walk in to the front room, tap a woman on the shoulder and say, ‘Let’s go.’ … Once we were in Memphis for an exhibition game, and Joe was hurt and didn’t come. I knew he always paid his own way for a suite, so I asked them to give me Namath’s room. It was a knockout. There was a circular bed, and fresh flowers, and a bottle of Scotch, and on the bed were these two envelopes with letters to Joe from women staying in the hotel. I’m in Joe’s debt. I certainly used those letters to my advantage.”

(What was it Namath said about his tastes? “I like my Johnnie Walker Red and my women blonde.” Of course.)

Quick story: One might Namath and Ed Marinaro, who was with the Jets then, are sitting in a New York bar, and it’s well into the shank of the evening, and Namath is preparing to go home with a woman who is not, to be kind, a drop-dead beauty.

Marinaro: “Joe, you were my idol, all through college, and I just can’t imagine you leaving a bar with anything less than a 10. And, to be honest, Joe, this woman, even on her best nights, is a six.”

Namath: “Eddie, it’s three in the morning, and Miss America just ain’t coming in.”

Conversations with Joe, Part II

“I’ve met ladies I’d like to know better, but when they already think they know what kind of guy I am, it turns me off.”

You seem so good with women.

“It’s a gift. And an effort also. Even as a youth, sitting at home, I can remember watching a comic work on television, and if he was bad I’d actually feel embarrassed for him and turn away. I can’t stand to see anybody feel bad, and if there’s anything I can do about the situation, to get people feeling up, I’ll do it.”

But you seem better with women than men.

“Maybe, yeah. I may put in more of an effort with women.”

Joe left the bar: “Eddie, it’s three in the morning, and Miss American just ain’t coming in.”

No, it’s more. You’re softer. You use a kiss like a prop. You defused a potentially angry situation with a woman at the Werblin dinner by holding her hand and kissing her on the cheek. You can’t do that with men.

“No, and I wouldn’t want to.”

But the difference in sensitivity?

“I’m more sensitive to the female, definitely. And I will take more time with a female than a man to get them more comfortable.”

You’ve never been married.

“No. But I wouldn’t mind.”

You’re terrific with older women and young girls, but some people suggest that you haven’t married because as much as you say you love women, you do not respect them, you’re jaded by so many women who have thrown themselves at you. Did you ever think of going someplace new—somewhere like Japan—to find a woman who could love you without your reputation preceding you?

“I’m happy now; I’m not looking for that one relationship. But it’s interesting that you mention that—you know, go someplace. I thought about it as recently as last week—packing up, moving to another place where no one knows me, just to see what it’s like. It’s a very real possibility. Not because I’m unhappy, but to see what it’s like. Somewhere where I’m nobody, where I’m just Joe. I’ve been a couple of places like that where I’ve just blended in.”

How was it?

He laughs. “I didn’t particularly like it that much. I like being known. If I was known as a rat or a bad guy it might be a problem. But, thank the good Lord, it’s usually a smile that I’m greeted with and, damn, I like that.”

“It’s true that Namath could have been on Monday Night Football. I very much wanted Joe in the booth.”—Howard Cosell

Although he plays an athlete (baseball) in Damn Yankees, and played a couch (basketball) on The Waverly Wonders, Namath has declined the most obvious trade on his former career—using the network sportscasting booth as a springboard to acting, à la Don Meredith, Alex Karras and Fred Williamson. When Meredith jumped from ABC to NBC some years back, Cosell, Namath and Roone Arledge met on Cosell’s terrace in Manhattan and Namath was offered Meredith’s job. He chose to remain active as a player, but since then, according to Namath, he and his longtime friend and attorney, Jimmy Walsh, have had discussions with all three networks about becoming a sportscaster.

“What’s bothered me is that maybe I haven’t worked hard enough in acting. Maybe I just don’t want to work that hard anymore. I’ve entitled myself to some rest. I’m sort of torn between the two.”

He has never done it.

He has, it seems, chosen the harder road by putting distance between himself and sports in trying to build a reputation as an actor. Calvinism, if you will.

But Calvinism may have nothing to do with it. Namath says, “Sportscasting’s not my style. Maybe part of it is that during my career I was so turned off by critics and announcers…. I got so irritated reading and hearing about what was wrong, and when it was good, it was too good….”

And then, perhaps more instructive, “It’s too confining. I need more room.”

“He’s never been the kind of guy to put on the yellow jacket and be there at four,” says someone who knew Namath from the early days. “When he works, he works exceptionally hard, but he never liked working, and he never liked anyone other than a coach telling him what to do. Outside football, with Joe it was always ‘My way or the highway.’”

It may simply be a question of work. How much? How hard?

At core, Namath is a sensualist, a seeker of comfort, who, more than anything else, wants his life to be “smooth.” He says he won’t dwell on the past; he says he can’t see into the future. Dick Schaap, who co-authored Namath’s autobiography, says, “Everything with Joe is today.”

Namath leaves no doubt as to his priority. “My dad worked 40 years in a steel mill. When I was at Alabama I worked 11 to seven in a paper mill. I chose football to get away from the mills. As hard as football was—and nothing I ever did was as hard as overcoming injuries—it was easier than the mills. I wanted to get to a point financially through football where I could have some leisure time and enjoy it, too. I’m geared to comfort.”

But Namath sees the problem that the tension between Calvinism and sensualism creates.

“What’s bothered me is that maybe I haven’t worked hard enough in acting. Maybe I just don’t want to work that hard anymore. I’ve entitled myself to some rest. I’m sort of torn between the two.”

He shrugs and smiles.

“I probably won’t get that far in acting with attitude I’ve got now.”

Yet, to decline the safety net of the sportscasting booth bears some witness to the sincerity of Namath’s effort to be an actor. Surely, it is courageous to play in Damn Yankees, to sing and dance each night in front of thousands. Yet, curiously, there appears to be no hunger, no urgency to commit to acting the way he did to football. It is as if he were training for the marathon by running the 440. Rather than see what he’s doing as insuring himself against failure, against psychological scarring, Namath sees it as “being realistic.”

The words of Merlin Olsen, another athlete-turned-actor, are read to him: “I don’t know of a single athlete who didn’t envy the draw of Joe Namath, the popularity of Joe Namath; it gave him a distinct advantage when he left football … [but] there’s no way you can walk in and compete with people who have 10, 20, 30 years in the business. You just can’t walk off the football field and onto the set and say—‘Okay, here I am. I’m the star.’”

Namath nods his head up and down and chuckles.

“I’ve only been at it a short time,” he says. “I don’t expect to be a superstar as an actor at this stage; I don’t ever expect to be in the same company as Robert Redford…. I’m not entitled to be a superstar in this field—I haven’t put in my time. The great ones have worked—they’ve paid their dues. I’m really just looking to get better.”

Namath says he is satisfied that his career is moving “at a steady, comfortable pace.” But he is aware that his larger-than-life status as an athlete may be detrimental to his career as a movie actor. Blow up a photograph too large and it becomes grainy. Namath doesn’t think he pops.

“Some people, I guess, hit it big as actors right off,” he says. “But I don’t think I will. I’ve already done four features and a television movie; if I had that super spark, that look or that charisma that jumped off the screen, I’d be doing more features. But I’m not one that jumps off the screen.”

Joe Willie White Shoes not having that super spark?

Broadway Joe not having that charisma?

Say it ain’t so, Joe.

“No,” Namath says, and he is serious. “If I did, I’d have been in more demand. I’ve had the opportunities. Nothing really mushroomed. It was a combination of things: My acting ability at the time; the roles I played; and me—I just don’t jump off that screen.”

This may be one reason Namath has opted for the stage over the screen lately. But even on stage he faces the problem of being victimized by his fame, what Jimmy Walsh calls “the credibility factor—would people accept Joe as the character he’s playing, or would they continue to see him as a football player?”

There’s no bitterness as Namath speaks.

“I’ve been told that there’s a problem to a degree in taking a star from one field and putting him into acting because people tend to remember what he did before rather than seeing him as an actor. And now I believe it…. When I see Jack Nicklaus on television doing a commercial, all I can think of is his golf tournaments. I’m proud of what I accomplished as an athlete, but I can see how it may hurt me as an actor.”

And then Namath tilts his head slightly and seems to stare through the wall of his Park Avenue hotel suite, past Lexington Avenue, past Third Avenue, past the buildings and the traffic—past everything concrete and clay—and says, “Eventually there’s going to be another generation that doesn’t know me from football, but that’s going to grow up seeing me work as an actor. That’s the generation I’m reaching for.”

You would think this “being realistic” might lead him to realize that he was on an inexorable downward shift on the talk-show couch of life. That the realization might bother him, might at least prompt some introspective questions like: Did I hit my peak on January 12, 1969, and is it just erosion control from there? Have I overrated my talent? Is this going to work? How long do I go with this, especially since I won’t commit totally? These are very human questions.

But Namath, for whom today is everything, is not the introspective sort. To be introspective would be a denial of his sensualism. So he dismisses it with a smooth line.

“It just amazes me that anybody takes the time to think of me at all,” he says. His smile is a piano keyboard. “I’m flattered that they care.”

In the necessary passage he is making from football to acting, although he has limited his work, when he has worked he has worked very hard. People who have worked with him attest to the fact that he shows up on time, studies his lines, takes direction well, becomes a part of the company. He has been through this all before. In football they say someone is “coachable.” Namath always was.

Tom Sinclair, who acted in Li’l Abner, says, “Joe is one of the most professional people I’ve seen onstage. A real craftsman. We rehearsed on cement in St. Louis, and the strain on his knees was such that he had to have them drained, and he still did the show.”

In any discussion of the transference of star quality from one field to another, there is a question of exploitation. Sinclair, for example, once told Namath it was “just a shame you have to cut your teeth in the big time, and you won’t get the chance to do your learning and make your mistakes in tank towns like the rest of us.” Steve Tannen, now a struggling actor himself, says, “You can’t put Joe in a character role or some two-bit work-your-way-up role because the public demands to see him as a leading man.”

Ben Piazza, who acted in The Waverly Wonders, says Namath was exploited: “It was a case of—‘Hey, we’ve got Joe Namath. Let’s use him quick.’” Jack Kroll, theater critic for Newsweek, who loves Namath’s work in commercials, talks of the danger from “schlockmeisters” who simply want to cash in on a name and demand that he carry a mediocre project solely through his charisma. Even Walsh says that Namath first started acting only because Hollywood people started throwing so much money at him that he couldn’t turn it down; it was only after Namath decided to do Picnic onstage two years ago that Walsh knew he was serious about acting.

Namath is succinct on the subject of exploitation.

“It’s a two-way street.”

But there is still the larger question of talent.

How much does he have?

Probably, like most athlete-turned-actors, less than Olivier and more than plywood. Really, it’s too soon to tell, and Namath’s unwillingness to make the total commitment makes it even harder to judge fairly. Commercials, which are almost mini-movies these days, attest to his charm and personal magnetism, but 60 seconds do not a feature make. Merlin Olsen, who made the transition from All-Pro to All Quiet on the Set, says he cringed the first time he saw tapes of himself acting. “I wasn’t showing nearly enough emotion. I had to learn as an actor that you have to tear away all the protections you spent your entire athletic career building up.” And Ed Marinaro, who is working regularly as an actor now, says, “Football is the ultimate macho sport. The greatest test of strength for an athlete is to play with pain. An actor has to show vulnerability, an athlete disguises it. The real hard part of the transition is baring your soul.”

Namath is listening and nodding again.

He says he’s getting better all the time at projecting emotions which are called for. But what’s frustrating is the narrowness of the roles he’s been given. Nice, sweet, warm, boring people, far less interesting than Namath himself, and the swinger type you’ve seen him do on Love Boat and Fantasy Island. “That’s acting for me,” Namath says. “That’s not me they see, the swinger.” What he wants to do is go against type, play a villain, a meanie. “I can really relate to that,” he says, almost leering. “But at this stage of my career my agent hasn’t felt that’s the direction to go.”

Namath is first in glamour and style, first in exemplifying the aggressive egotism that New Yorkers consider part of their birthright. Whether he ages with dignity and grace, whether he carries a lasting presence or becomes celebrated in marriage and song like DiMaggio, who knows?

As a player Namath was so embarrassed by his voice that he sang the national anthem to himself. He is still unsure of it, even with lessons and coaching. Recently, he was exercising his voice by doing scales in a steam room after swimming 32 minutes of hard laps, and he stopped abruptly when another swimmer came in, later explaining, “I was afraid I’d scare him.” Most often in rehearsal he was on target, but no, Pavarotti is not yet an endangered specie.

“Actually, his voice is quite good, considering the limited training he’s had,” says Joseph Klein, the Damn Yankees musical director. “I know he’s self-conscious about it, but it’s big and strong and, like any instrument, the more he uses it, the better it’ll get. He’s doing some tough harmonies in the this show, and I think he’ll surprise himself at how good he’ll be.”

Dancing, however, is off the board.

He and Fred Astaire have this in common—80-year-old knees.

Namath does not kid himself. He is in pain every day. He can’t flex his right knee; he can’t straighten his left leg; he cannot run three strides at full speed. He is arthritic and every day he works he has to take arthritis pain pills. The nightly dampness at Jones Beach will make his knees feel like the San Andreas fault is in there on a summer rental.

He is riding from the pool to the rehearsal and the subject is musicals.

“Did you see Yankee Doodle Dandy?” he asks. “Isn’t Cagney something? Now that guy could really hoof.”

He shakes his head in admiration.

“Tell you what,” he says. “I never bitch about my knees because I know I’ve had it pretty good. But I sure do wish I could dance. I sure would like to have the wheels.”

Names come up. Gene Kelly. Baryshnikov. Astaire. Namath says he was at a dinner for Astaire and saw all the old film clips of him dancing; now that was really something.

The cab stops.

While walking the few steps to the stage door, someone from the cab says to Namath, “Bet you’d like to come back one day as Fred Astaire.”

Namath doesn’t bat an eye.

“Not me,” he says. “I’d like to come back as Secretariat and be at stud.”

Conversations with Joe, Part III

“I didn’t drink [liquor] in college. Started drinking in the pros. We played up in Boston. I got hit on a safety blitz, got a real deep bruise on my hip and butt. When I got home that night it hurt so bad I could hardly get out of the car. I didn’t have any pain pills … so I got some Scotch because it was the worst-tasting stuff I could find.

“Johnnie Walker Red kicked my ass! Like any whiskey, it’ll beat you. I drank Scotch for five years and I found that the only time I ever got nasty, belligerent, angry was when I was drinking…. So I quit drinking Scotch to drink something easier. I mostly drink vodka now.”

Smirnoff, right?

“I’m an American. That’s right. These people talk about that Stolichnaya and stuff—to hell with the Russians. I’m honest-to-God pro-American, and I boycott every damn Russian thing they have—I don’t like ’em, don’t like their attitude … I’m a Smirnoff and Wolfschmidt drinker when it comes to vodka.”

Didn’t you quit drinking once?

“Quit for close to two years. I was over in Germany in ’78 for three and half months, making a movie with Bob Shaw, Lee Marvin and Mike Connors, and we were out a whole lot of the time, drinking. This one day we were at the studio in Munich and Bob and Lee and Mike were doing a scene together, and I’m watching them, trying to pick something up. I felt a little strange. I held out my hand and it was shaking. That’s when I decided to quit. That night was my last night of drinking, and I finished the evening by drinking a whole bottle of sherry….

“[In those two years] I slept better than I ever slept. I felt great…. Had this gooood feeling, but it was soooo boring. I’d hardly ever go out. I didn’t want to be standing around in a smoke-filled room with everybody drinking and me just standing there. It was totally boring.”

“Some nights I party. Listen, you can party till it’s light in Fort Lauderdale sometimes. Of course, it’s very difficult to hoot with the owls and soar with the eagles.”

Do you get drunk often now?

“No. Occasionally I get drunk, hell yeah. But not the kind of drunk I’d gotten in the past … I enjoy drinking. But never during work…. You’ve got a responsibility. You don’t just represent yourself, you represent your people.”

You don’t drink to kill the pain?

“No. No. But what got me started was a pain in the ass.”

Travels with Joe, Part II

Of all living athletes whose star is tied inextricably to New York, there is only one who suffers no generation gap, only one whose fame seems eternal. DiMaggio.

Of the others who come to mind—Mays, Mantle, Snider, Gifford, Namath, Reed, Reggie, Seaver—Namath seems the favorite to inherit the turf. They were all winners, but only Namath was the architect of something stunning, something endemic of a cultural movement; his solitary moment seems now to magnify its impact.

There is no shyness in greeting him. They sense that he is happy for the contact, that he welcomes it. You get the feeling you are in the middle of an I Love New York commercial.

And among many, Namath is first in glamour and style, first in exemplifying the aggressive egotism that New Yorkers consider part of their birthright. Whether he ages with dignity and grace, whether he carries a lasting presence or becomes celebrated in marriage and song like DiMaggio, who knows?

But it is clear now that New Yorkers love him. Justifiably, they see him as a populist, one of their own. They see him on the street and they call to him. They stop their cars for him. They give him their ultimate tribute of acceptance, the passing comment of familiarity. He makes New Yorkers smile, which is almost impossible.

He is walking briskly on the way to the second day of rehearsal, walking down Fifth Avenue.

“Good to see you, Joe.”

“Looking good, Joe.”

There is no shyness in greeting him. They sense that he is happy for the contact, that he welcomes it. You get the feeling you are in the middle of an I Love New York commercial.

“Joe, you’re walking pretty good. Guess the knees are okay.”

“Joe Willie.”

Namath is so taken by the good vibrations that he starts to sing.

“Bum-BUM. Bah-bah-bah-BUM. Bah-Bah.”

Three cab drivers are watching and listening as Namath does this. Cab drivers have seen everything.

“Hey, Joe,” one of them calls out. “You want to keep it down. It’s still early in the morning.”

Namath laughs and his face is the color of tomato.

Conversations with Joe, Part IV

Joe, now that you’re 38 and heading into middle age…

“Uh-uh.”

You’re not heading into middle age?

“We don’t all get there. You’ve got to be lucky to get there.”

You have to be lucky to get to old age…

“No, you’ve got to be lucky to get to middle age. A guy told me yesterday about a buddy of mine I hadn’t seen in three months—he’s dead. Last time I saw him was in this room—he’s dead. In his shoes in his short 30s. We got to be lucky to get there.”

You’ll get there.

“I hope so.”

Are you afraid you’re going to die?

“I know I’m going to die; I just don’t want to die soon. I’ve seen good people struck down early. I’ve had friends who’ve died young. You don’t know when it’s going to come—you’ve got to be lucky…. I’ve given it some thought, and I know you have to be lucky to survive. You just never know when something’s going to jump on your back…. People say, ‘You’ve got it made, man.’ I say, ‘Made?’ Look, I plan on living past 100; I’m 38 years old. If I’m 38, and I see life like a football game, I’m in the second quarter. I’ve seen too many game settled in the third and fourth quarter. I’m not settling down now. I ain’t got nothin’ made.”

“His career hasn’t soared, but it doesn’t bother him. Not as long as he enjoys it.”—Dick Schaap

Money doesn’t seem to be a problem. Putting aside whatever earnings Namath has from acting, Faberge pays him $250,000 per year for its Brut campaign and other corporate appearances. Namath has two other long-term endorsement deals, with Franklin Sporting Industries and Dynamite Classics, which manufactures Joe Namath luggage and Joe Namath exercise equipment. All told, Namath probably earns about $400,000 per year from these relationships. And that doesn’t take into account his real estate investments which includes development of shopping centers.

Walsh says that Namath will not even consider new endorsement packages for less than $100,000. Nor will he do any national one-shot commercials. (Remember Namath’s pantyhose spot, or his mustache shave-off for which he got $10,000, and which ran only once on each of the three networks? Of course.) Namath has done regional ads in which he is incidental, as in his cameo for the “Schaefer City” campaign for Schaefer beer, which runs in the New York area. But for national endorsements, Walsh wants Namath to be the campaign spokesman or don’t bother asking. Namath turned down an appearance in Detroit last year, which would have paid $25,000 simply because he wanted to stay at home in Fort Lauderdale and watch a televised football game.

Ah, Florida.

“I get up early in Florida,” Namath says. “I’m up between seven and eight; you don’t want to waste a day in Florida” Then it’s a full day of fishing, snorkeling and golf. “That takes us through the whole day,” he says, “Some nights I party. Listen, you can party till it’s light in Fort Lauderdale sometimes. Of course, it’s very difficult to hoot with the owls and soar with the eagles.”

Leisure time. No steady job. No nine to five. No mill. Fun in the sun. A small circle of friends. Fun in the shade. No more safety blitzes. No more torn hamstrings. No more boos when the pass sails long. No more critical stories in the newspapers. No more splints. No more tape.

And the money keeps coming. Wasting away in Margaritaville.

“I just really want things to be smooth,” he says. “I do my best at keeping things smooth and calm.”

Not getting older, getting better.

“Life is better,” he says. “I know it’s better. Everything about life to me at this stage is better than it was. I know better routes to achieve the feelings I’m looking for. Now I’m living in a smoother, more comfortable manner.”

The sensualist.

Joe Namath may be one of the easiest people in the world to get next to, if not close to. The soft, caressing handshake. The radiant smile. The gorgeous green eyes. The kiss on the cheek for the ladies. “How are you?” “Oh, it’s so good to see you.” “Thank you so much.” In the instant he meets you he puts you at ease, as if the rest of the world simply does not exist, and it’s just you and him—just you and Joe.

And they love it.

They all just love it.

Why do they all love him so?

There isn’t the slightest hesitation in his voice.

“I’m lucky; I was born with the gift.”

[Featured Image by Jim Cooke]