In the fall of 1993, the ominous letters and phone calls began to come in to Gerald Levin’s office on the top floor of the Time Warner Building in Rockefeller Center. There weren’t hundreds of them, but each was from somebody who really mattered to the chairman and C.E.O. of the media conglomerate. Levin heard from, among others, David Geffen, Michael Ovitz, Barbra Streisand. Clint Eastwood, and Paul Simon. And they were all expressing the same fear.

Something unthinkable appeared to be happening to Mo Ostin. The 66-year-old patriarch of Warner Bros. Records—the most successful and beloved executive in modern popular music, whose L.A.-based label was known for creating more value, financially as well as musically, than any other—was being unceremoniously forced either up or out. And the creative community wanted Levin to know just how disastrous such a move might be. Some of Warner’s top acts were starting to panic: Madonna had talked to Anthony Kiedis of the Red Hot Chili Peppers about circulating a “Just Save Mo” petition to Neil Young, R.E.M., Eric Clapton, K. D. lang, Rod Stewart, and the rest of the stellar roster. When Madonna called Ostin to make sure it was O.K., he, perhaps unwisely, told her it wouldn’t be necessary.

“Mo is the single most important music executive in the world. I compete with him every day, and he still beats our brains in more often than not.”

All the warnings went unheeded. Levin wasn’t even swayed when Geffen publicly confronted him last July at the annual retreat of multimedia powers-that-be that consultant Herbert Allen hosts in Sun Valley, Idaho. “You’re making a terrible mistake,” Geffen lectured Levin in front of a whole table of lunching members of the New Establishment. “Mo is the single most important music executive in the world. I compete with him every day, and he still beats our brains in more often than not. Jerry, this is not a good idea for you.”

The music business and Wall Street are still stunned by how much worse the situation became than any of these worried influential people predicted. The entire $5.4 billion Warner Music Group—which includes the Warner Bros., Elektra, and Atlantic labels, and is not only the world’s largest record company but also arguably its largest repository of good music—went spinning out of control. Ostin and another legendary record man, Elektra’s chairman, Bob Krasnow, were forced out by their corporate nemesis, Bob Morgado, when he promoted the head of Atlantic, Doug Morris, over both of them. Morgado also nixed the new contract that Metallica, one of the biggest acts in the Music Group, had been negotiating with Krasnow. causing the band to sue and Time Warner to countersue for $100 million. Then the Warner executive who succeeded Ostin decided he didn’t want the job, and Morris declared war on his own benefactor. Or, as one top record-company executive delicately put it, “Morgado’s pawn ended up kicking him in the nuts.”

There was so much spin control and on-line gossip that the war became public, the juiciest, most emotional entertainment-business story the media had fought over in years. Eventually Jerry Levin was persuaded to intercede after all—reportedly by some of his Time Warner board members. The once stable conglomerate found itself acting out what one particularly angry British Warner executive has come to refer to bitterly as “the Play.” But it was more like a block of overwrought music videos, full of angst-ridden mixed metaphors such as the one invoked by Metallica drummer Lars Ulrich. “I was pissed off more on a personal level,” he said, “but I didn’t think it would open up the floodgates to a four-month shitstorm.”

It was during a calm in that storm that I visited Mo Ostin at Warner Bros. Records, housed in a three-story wooden structure on the periphery of the Warner Studio in Burbank. To get to his office, I was led through tall hallways decorated with years of rock history. This was, after all, the label that could take credit for the recording careers of Jimi Hendrix, Joni Mitchell, Van Morrison, the Grateful Dead, Rickie Lee Jones, Talking Heads, the Sex Pistols, Dwight Yoakam, and Chris Isaak, as well as the second comings of George Benson, Paul Simon, and Elvis Costello. The posters that dominated the wall space were plain black rectangles. They were meant to herald the release of Prince’s infamousBlack Album, but they also pretty much summed up the mood of many of the people who worked there.

Ostin is a small, balding man with a surprisingly big voice and thick tortoiseshell glasses that never stay up on his nose. On his left wrist he wears a 150-year-old Patek Philippe watch. It was presented to him at the Warner Music International meeting in Montreux, Switzerland, last June—a gift he found a little suspicious at the time, since he wasn’t planning on retiring. Ostin talks with his hands, and his eyes squint nearly shut when his face shows emotion. When I asked how he felt about everything that had happened, he pressed his fingertips together and squinted. “It has been incredibly painful,” he said. “I’m not sure that people thought out the consequences to this company when they were making these decisions.”

In New York. Ostin’s friend Bob Krasnow, the 59-year-old deposed Elektra chairman, was similarly grieved. “How did all of this happen?” he asked. “Why would a man burn down the most beautiful house on the block with all the beautiful stuff still in it? Why?”

The man accused of burning down the house is Robert Morgado, the 51-year-old Time Warner executive whose clumsy execution of Machiavellian principles suggests that he may have read only the Cliffs Notes to The Prince. The Hawaiian-born Morgado has a broad smile and unusually large, strong hands, which can turn a handshake into a subtle wrestling match. He came to what used to be called Warner Communications from politics in 1983—he had worked for New York governor Hugh Carey—and he built a reputation as the company “hatchet man” after lowering corporate overhead by a staggering 70 percent in only two years. Morgado was then put in charge of recorded music and music publishing, but most of his efforts went into a successful expansion of the international business rather than a lot of involvement with the domestic labels, where he was initially seen as a liaison rather than a boss.

Steve Ross, the longtime chairman of Warner Communications, who let his U.S. label chiefs run their own shows, was the boss—a man who clearly understood the space and trust that people in artistic commerce needed to do their jobs. And as long as Ross was there, it didn’t matter that Bob Morgado was strong and smart but—when it came to dealing with record people—just didn’t get it.

In 1990, when Warner merged with Time, Morgado was given more power as head of the renamed Warner Music Group. Instead of just working on international—which he saw as a new business frontier where he could make his mark and which the U.S. label chiefs saw as primarily an expanded pipeline for their recordings—he started analyzing the bicoastal family he wanted to do more with than baby-sit.

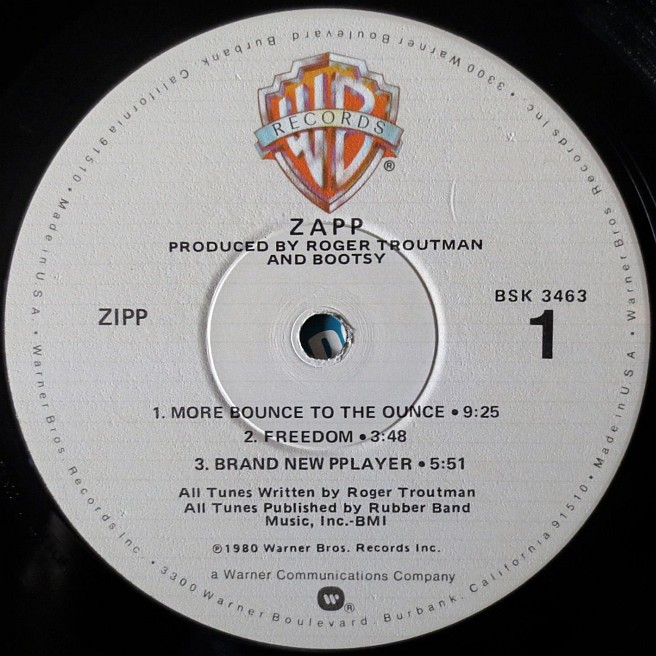

The strength of the Warner Music Group was that the labels competed against one another as independent entrepreneurial siblings with strong personalities, whose products were all distributed by the parent business. For more than a decade, Warner’s under Mo Ostin was the laid-back favorite son. Ostin had been brought into the company by Frank Sinatra in the early ’60s to run the singer’s own subsidiary, Reprise, to which Ostin later signed Jimi Hendrix, Joni Mitchell, and Neil Young before taking over Warner Bros. Records itself. The label blossomed in the ’70s and became a juggernaut by the ’80s, helped especially by its hip Sire subsidiary (which signed Madonna, Talking Heads, and K. D. lang), the breakthrough success of R.E.M., and the accumulated might of its catalogue. Ostin’s protégé was boyish former producer and studio brat Lenny Waronker, whose work, beginning with Randy Newman and James Taylor, embodied the Warner’s ethos of building career artists by letting them do their own thing.

The eldest son in the Music Group was Atlantic, under co-founder Ahmet Ertegün, the goateed, erudite, Turkish-born wizard who had started his New York-based label in the late ’40s, built it on excellent jazz and R&B in the sometimes ugly business of the ’50s and ’60s, and sold it to Warner by the ’70s, when the label had its heyday with Crosby, Stills & Nash, Led Zeppelin, andAretha Franklin. By the ’80s, Atlantic had long since given up its birthright of musical leadership and was still making money the old-fashioned way: by throwing thousands of mostly derivative new records against the wall and seeing what stuck. Its roster, under the semi-retired Ertegün and his protégé, Doug Morris, was considered something of an embarrassment, with its semi-hard-rock acts, which were referred to as “hair bands.” The label’s saving grace, apart from its catalogue, was the fact that Genesis drummer Phil Collins had inexplicably become a top-selling rock star.

Elektra was always the eccentric, artsy son, often misunderstood and ahead of its time, just like its first hit act, the Doors. In the mid-70s, the L.A.-based label had been merged with Atlantic’s newer, better West Coast label, David Geffen’s Asylum—home of the Eagles and Linda Ronstadt, which Geffen sold after a cancer scare—but it eventually ran out of steam. Then, in 1983, Elektra found a perfect match in brash former Ostin talent scout Bob Krasnow, known for his bold artist-collecting (Chaka Khan, Captain Beefheart, George Benson, Devo) and partying, which reportedly inspired Randy Newman’s “Uncle Bob’s Midnight Blues.” He moved the label to New York, and his extravagant taste and sometimes overbearing self-confidence helped him revitalize Elektra as a boutique label. He became a critics’ darling for proving that there was still a place at the top of the charts for esoteric pop musicians such as 10,000 Maniacs, Tracy Chapman, Anita Baker, and the smartest of the metal bands, Metallica. And he was befriended in the New York art community because he collected—his office was dominated by a Robert Longo—and encouraged his Nonesuch division to record tony modern-music groups such as the Kronos Quartet. As the self-appointed conscience of the Warner Music Group, Krasnow often publicly criticized the musical taste of Elektra’s big brother label Atlantic.

When Morgado took over the Music Group, Elektra’s Krasnow and Atlantic’s Morris started reporting directly to him. But Mo Ostin refused. The five-year contract he had signed before Morgado was promoted said he reported directly to Steve Ross. “My hang-up wasn’t so much the ‘reportage’ issue,” says Ostin, “and, of course, ‘reportage’ is one of those terms Morgado loves, like ‘grow the business.’ … My hang-up was that he and I were so philosophically apart. He wanted control … and I just did not like the way he dealt with me. To me it wasn’t so much the reportage as it was the man who was the problem.”

Morgado recalls their relationship differently. “There was friction with Mo, but I don’t think I would characterize it as personal,” he says. “It was a disagreement on philosophy .… What had worked for one concept of the business was no longer viable, and that is the conversation we had for years. Back then it was a different company, with fewer assets under management and less moneys invested in the corporation. He was still saying, ‘I don’t believe you should exist, Bob.’ ”

“Look,” says Bob Krasnow, “this business is built on the emotional connections between the artistic community and the buying public. You become successful if your judgments, however they’re made, have connected to the audience at large. So suddenly Mo should be reporting to a guy who’s not a music man? What does he add? It doesn’t mean he’s a bad man: he’s not an asshole or a prick. But what does he teach me about me that allows me to do me better? If you can bring a person who does that into my life, I’ll hug you. There is a list of people who are like that. Bob Morgado is not on that list .… You know what he would always call us? ‘Content providers.’ ”

The dreaded “reportage issue” didn’t become terribly problematic for Ostin or Krasnow for several years. Atlantic took most of the heat. Morgado, like most of Atlantic’s competitors, believed the label was “moribund.” According to Ahmet Ertegün, Steve Ross was talking about firing Morris in 1990. Ertegün encouraged Ross to offer Morris renewed support instead. Ross refused. But Bob Morgado gave Morris another chance and more power to control his own fate; he made him co-chairman with Ertegün. The reason may have been that Ertegün and Morris were the only ones in the Music Group who shared Morgado’s vision. “When Morgado came, I think he had a philosophy which was more in line with what I had always felt,” says Ertegün. “He wanted to somehow unify these three labels and effect savings wherever he could, and stop the fierce competition between the labels. We cooperated with Bob Morgado. And he was very supportive of Doug.”

Morris is an amiable former songwriter (“Sweet Talkin’ Guy”) and independent-label owner who looks like a stockier, bearded version of comedian Alan King. Like many record people, he is more comfortable waxing nostalgic about the music of his past—the songs he loved, the artists and the executives he worshiped (including Ertegün, whose office is next to his and whose wall he bangs on when he hears a good tune)—than discussing the business of today. Always well liked even if he wasn’t always well respected musically, Morris was still very much a record man when he got his shot at age 50, and he was smart enough to partner with some better ears. His masterstroke was to help legendary producer Jimmy Iovine (U2, John Lennon) start his own L.A.-based label, Interscope, with movie producer Ted Field. Besides some smart signings of his own, including Nine Inch Nails and gangsta rapper Tupac Shakur, Iovine’s masterstroke was to make a deal to distribute the rap label Death Row, which produced top-selling Snoop Doggy Dogg and Dr. Dre. Interscope became the most successful start-up label the industry had seen in years.

Morris made 38-year-old Sylvia Rhone the first black woman ever to run a major label; her EastWest Records would mine multi-platinum by marketing En Vogue as a Supremes for the ’90s. Morris also hired 42-year-old Danny Goldberg—who looked more like a schlumpy liberal lawyer than a music guy who co-managed Bonnie Raitt and Nirvana—as his senior vice president and most trusted strategist. He started a video division, A*Vision, which sold music and exercise videos. And he bought a stake in Rhino Records, and gave its reissue experts free rein on the underachieving Atlantic catalogue.

Just as Atlantic started rebuilding, illness began to change the emotional balance of power within the Music Group. In 1991, both Steve Ross and Bob Krasnow found out they had cancer. For Ross it was a recurrence of the prostate cancer he thought he had eradicated years before. For Krasnow it was a lymphoma in the knee.

Krasnow’s treatment worked. But even though his cancer had become known during a banner year for Elektra—the year Natalie Cole’s Unforgettable and Metallica’s eponymous blockbuster dominated the charts and Grammys—his predictable physical deterioration during chemotherapy and his increasing interest in nonmusic projects (including an Elektra co-produced film of Tchaikovsky’s The Nutcracker with Macaulay Culkin and the New York City Ballet) gave all the people he had pissed off over the years ammunition to use against him. By the time he was declared cancer-free, his stock within the Music Group had fallen. His criticisms of gangsta rap were no longer viewed as constructive. And he wanted to keep his label a boutique, which didn’t fit Morgado’s plan to “grow” the Music Group.

Steve Ross’s treatment didn’t work. He died in December 1992, and his lauded ability to let record people be record people as long as they made money died with him. His eventual successor, Jerry Levin, decided that the label chiefs would no longer be allowed to end-run Morgado and come directly to him. Suddenly Mo Ostin’s problems with Morgado became a serious matter.

In the fall of 1993, word went through the industry that Morgado was playing hardball with Mo Ostin. The issues were reportage and succession. Morgado insisted that Ostin’s next contract must stipulate that the music executive report to him, just as all the others did. When Ostin appealed to Levin for help, the Time Warner C.E.O. sided with Morgado. Then there was a dispute over the timetable for Ostin’s succession. “Some people don’t do well with their own transition, their own mortality,” says Morgado. “Mo was difficult because he could not deal with the idea that somebody in his own company could be equal to him. It’s very human, I understand that. But then he turned me into the issue. And, to me, well”—and at this point Morgado raises his voice for the only time in a two-hour interview—“it’s all really bullshit, frankly. To me, this is ultimately about how companies handle changes in their executive management.”

Ostin disagrees. He says he went to Levin to propose a new contract and a succession plan which would have given his protégé, Lenny Waronker, three years to make the job his own. The succession plan was shot down. Morgado wanted Lenny in place in a year and a half. After several uncomfortable months, during which Ostin’s friends contacted Levin in his behalf, a deal appeared to have been reached—mostly on Morgado’s terms. But Morgado neglected to tell Ostin that he had already started talking to Doug Morris about a newly created job overseeing the entire Music Group—a job which would require Ostin to report to Morris too.

It was all part of a trend that some Music Group insiders were starting to worry about. They called it “Atlantification.” Months earlier, a friend of Bob Krasnow’s from the film business had recounted to him a dinner conversation he had had with Morgado. The friend said Morgado had told him that Atlantic Records was the future of the Music Group.

The concept stunned Krasnow. Atlantic Records, the least credible label in the Group for a decade, has one great year and it’s now the future of the Warner Music Group? Was this the same Warner Music Group that had thrived with three unique musical cultures—dominated by Mo Ostin’s operation at Warner’s—for 20 years, and that currently controlled the largest single share, more than 21 percent, of the $10 billion U.S. record business, and had $3.8 billion in music revenue worldwide? (Warner Music Group’s closest competition in the U.S. is Sony, with 15 percent of the market, followed by BMG, Polygram, EMI, and MCA. Each of the majors has about 10 percent of the other $20 billion in world sales, half of which comes from Japan, Germany, and the U.K. The $10 billion domestic recorded-music market is smaller than domestic book publishing, at $18 billion, and film entertainment, at $27 billion, but is considered a cash cow, because the initial capital outlay for records is often quite small.)

Krasnow called Mo to tell him the news about “the future.” He then called Morgado, who insisted that Krasnow’s friend had misunderstood. But fear of Atlantification was in the air at Time Warner, and it didn’t help that both Warner Bros. and Elektra had hit slow periods. Krasnow’s Nutcracker movie didn’t do well, a boxed set by Metallica did only O.K., and new releases by Natalie Cole, Linda Ronstadt, and Anthrax stiffed. Warner’s ’93 was saved by Eric Clapton’s surprisingly successful Unplugged, but other top acts fizzled. Warner’s hadn’t had two records in the Top 10 simultaneously for many months. Neither Elektra nor Warner’s was having much luck breaking new bands, and both were canceling once hopeful label deals—including the multimillion-dollar package for the artist who stopped calling himself Prince.

Meanwhile, the press coverage of “the Atlantic story” was starting to catch on, following a December 1993 cover story in Billboard. The piece explained how the Atlantic Group had increased revenues 55 percent in just two years. During a different era in the history of the Music Group, such an article would simply have meant that Morris and Atlantic had finally achieved the credibility and success that Mo had had for decades and Krasnow had enjoyed since the press discovered “the Elektra story” in similar articles during the late 80s. It might have made Mo and Lenny and Krasnow focus more, prune some dead wood, and find some new acts—especially after the Music Group’s 1994 Grammy party at New York’s American Museum of Natural History, where a few too many jokes were made about reliance on “dinosaur acts.” Instead, the press just reinforced Morgado’s ideas about Atlantification.

But the press also exposed the first glitch in the relationship between Morgado and Morris—they started tripping over each other trying to take credit for the Atlantic comeback. Even as they were discussing how Morris could be put in charge of all the U.S. labels, their publicists were trying to make sure that the “hail Atlantic” stories were about the right guy. It was a time-honored tradition in the music business to take credit for anything good that happened while you were in charge—or merely standing nearby. But Morris and his executives couldn’t believe that their corporate boss seemed to be doing it. And they were stunned by the attitude of Margaret Wade, Morgado’s brassy publicist.

“Margaret Wade was constantly complaining that Doug was getting too much press,” says one Atlantic insider. “This was a big source of tension.” Margaret Wade denies this. She admits that she wanted to know ahead of time about stories in the business press. But she says her main concern was the way Atlantic was publicizing its success. The label was “breaking out” its numbers from Soundscan, the company that determines the country’s top records, and encouraging journalists to compare Atlantic and Warner Bros. “It is against company policy to break out numbers on the domestic labels,” Wade says. “You know how cyclical the music business is.” It was true. And because several of Warner’s top acts—R.E.M., Madonna, and the newly signed Tom Petty—weren’t bringing their new releases out until the fall, there was actually a brief period between April and July when Warner’s market share dipped below Atlantic’s. It was during this window of Atlantic opportunity that Bob Morgado lowered the boom.

After he was given his antique watch at the Warner Music International meeting in Montreux, Mo Ostin was pulled aside by two executives who wanted to know why he still hadn’t signed his new contract. Ostin’s lawyer’s son had been ill, and that seemed like a good excuse to put it off. But the truth, he recalls, was that “something within me told me not to sign it.” Just after July 4, Krasnow had a late-afternoon meeting with Morgado. He thought it was to discuss the new contract he had been negotiating with Metallica, which had sold more than 20 million records for Elektra since 1984. Instead of the customary huge cash advance, the group wanted to joint-venture on their upcoming releases and to buy back the master recordings from their previous ones. And they claimed to have an ace-in-the-hole bargaining position. They believed they could declare free agency from their existing contract by invoking a California law making personal-service contracts unenforceable after seven years. The band’s managers were anxiously awaiting the results of the meeting. But the subject of Metallica was not on the agenda.

“Bob goes into this kind of schematic diagram of how the company is structured.” Krasnow recalls. “I’m sitting there kind of stunned—what are we talking about? And finally it’s dawning on me that something is changing here. He gets to the point that because of this tremendous workload and the hugeness of the company and all this he was making Doug Morris the president of the U.S. Music Group, and Mo and I were going to be reporting to Doug. I don’t say anything: I’m stunned.

“Finally I just say, ‘I have to digest all this, Bob, and get back to you.’ I leave and come home and call Mo, who is in London. I said, ‘Mo, guess what. You have a new boss. His name is Doug Morris.’” Ostin, who had once turned down almost the very same job Morris was getting, immediately arranged to fly to New York and meet with Morgado.

Ostin and Morgado have different recollections of that meeting. “Mo thought it was a good idea when I discussed it with him,” Morgado says. “He said, ‘I can understand your reasoning,’ and did not argue against it .… He sounded positive.”

Ostin agrees that he said he understood, “but I never assented.” He says he asked Morgado what the time frame was for this decision and was told “later in the summer.” He says he asked who else knew and was told he, Krasnow, Doug Morris, and Time Warner C.E.O. Jerry Levin—absolutely nobody else. “I left and flew to Aspen, and when I got there I was told by my son that he had heard from a top executive that this was going to happen,” Ostin says. “I spoke to that executive and confirmed it. He said he heard it from somebody else. So I called this other person. So now I already know three people who know about it. One of them heard it from Doug Morris before I was told.

“Then I get back to L.A. on Monday and I learn that on Friday, the day after I was told, Chuck Phillips at the L.A. Times knew, and, after the weekend, he got a press release about it that even quoted Morgado. I called Morgado, and that pretty much confirmed for me all the fears I had about signing that contract. This all left me feeling betrayed. I called Morgado and said, ‘I’ve decided I’m not signing my contract. I will fulfill my existing contract, and at the end of the year I will leave.’ I called Doug and told him the same thing.”

Krasnow tried a different approach. After a few days of consulting with lawyers, he called Morgado and said he thought he could make it work. “And there’s dead silence on the other end of the phone,” Krasnow recalls, “because this is the last thing the guy wanted to hear. I said, ‘Why don’t I meet with Doug Morris?’ We set up a meeting for the following Tuesday. Well, of course, that wasn’t going to happen. Ahmet Ertegün called me on Monday night and told me he was a ‘friend of the court,’ and asked if there was something else I would like to do in the company. Doug Morris could ensure I could have anything I wanted .… We all feel Ahmet’s shaky hand behind all of this, right?”

Krasnow quit the next day. He wasn’t allowed to speak to the press while his exit deal was being negotiated—and his replacement, EastWest’s Sylvia Rhone, who had once been his director of black marketing before going to Atlantic, was being named—so his resignation got lost in the press coverage of all the doings at Warner. Morgado believes it was the press speculation that caused Mo Ostin to step down.

“I think that’s what changed Mo’s mind, 100 percent,” Morgado says. “He said he was uncomfortable with the way the issue had been covered: it made him look bad. I think that’s it.”

Ostin bristles at this suggestion. “I think my ego is in pretty good check,” he says. “You can talk to people about my ego and then talk to them about Morgado’s ego.” One Warner executive summed up Morgado’s ego this way: “He is what’s wrong with the record business. They put these nonmusic guys, these fucking broccoli salesmen, in charge, and then they treat us like we’re all fungible. Record people are not fungible!”

Morris flew to California to try to change Ostin’s mind. “Doug was terrific and said all the right things.” Ostin recalls. “But I indicated to him that that probably wouldn’t happen, and I reassured Doug that it wasn’t about him.” It took another month of negotiations and phone calls to iron out the details of a consulting contract with Levin, but the Mo Ostin era at Warner’s was over. The best hope for his admirers was that his handpicked successor, 52-year-old Lenny Waronker, would carry on in his tradition.

Although the circumstances of Waronker’s promotion were mortifying, this was the job for which he had been groomed for 12 years. And even though Mo hadn’t signed his contract, finalizing the succession plan, Lenny had gone out of his way to meet with Morgado to start building a relationship with his new boss. He was determined to make it work, “no matter how angry I was about what went on” between Mo and Morgado. Waronker was given the job, and the marketplace seemed to embrace him: Warner’s drought on the charts ended as two new bands, Green Day and Candlebox, broke big and monster releases from R.E.M., Eric Clapton, and Tom Petty were poised to invade the Top 10.

Morris filled his old post as head of Atlantic with Danny Goldberg—who was well liked and could claim recent successes with Stone Temple Pilots and Liz Phair—and peace was declared. When Bob Morgado was profiled in Business Week on September 5, the spin was that he was “now firmly on top of his often feuding labels.” Nothing could have been further from the truth.

Doug Morris thought he had been given a real job. But he immediately began to wonder if his new position as head of the U.S. labels really existed. His first major tip-off that the industry gossip was true—that perhaps he was just Morgado’s pawn—came after an August meeting with Jimmy Iovine and Ted Field. Atlantic owned just over 25 percent of their label. Interscope, and now wanted to exercise its option to buy the rest. Iovine and Field had been told to solicit bids from other labels to set a price for their share—which was about $300 million. The meeting went well: “Morgado hugged Ted and Jimmy at the end,” says one source. But afterward, without telling Morris. Morgado contacted the labels that had provided the bids and threatened legal action if they actually tried to buy Interscope. Iovine and Field were livid, and Morris was mortified: the first important negotiation of his career had been tabled because of Morgado’s meddling.

It was the beginning of many phone calls and visits between the 4th floor of the Time Warner Building, where Morris had his office, and the 30th floor, where Morgado worked in a stereo-free environment. “Morgado kept taking actions without consulting Doug and then would say, ‘I’m sorry, I was misunderstood,’ whatever,” says one Music Group executive. “He became like the drunken husband who keeps doing things and then apologizing.”

In late September. Metallica filed a lawsuit to get out of its Elektra contract. Lars Ulrich, the band’s drummer, made it clear that “the fucking enemy” was “this fucking asshole” Bob Morgado. With Krasnow gone, Morris and Morgado had nixed the proposed Metallica contract, made what the band’s managers felt was a lame counterproposal, and let them languish for weeks at a time between communications. With the Metallica suit, business and entertainment reporters suddenly had a much more provocative story, one for which sources very close to the situation seemed unusually willing to talk.

“Every little argument became public and hit the press … a lot of people talked,” laments Ahmet Ertegȍn. “You know, there were changes at Sony, changes at Polygram, changes at EMI, MCA. If people had been giving blow-by-blow accounts for two weeks prior to those changes, there would have been mayhem that would make this look like a Sunday-afternoon picnic. But it is our fault that it got out.”

Once the October 28 issue of Entertainment Weekly hit the stands. Morris was up in Morgado’s office and they were really going at it. The soon-to-be-leaked argument du jour: rankings on the magazine’s annual “Power 101” list. According to E.W. manuscripts obtained by Vanity Fair, on one draft of the list Doug Morris was on his own at No. 17, with Morgado further down. On a subsequent draft. Morgando and Morris were sharing No. 17 (because the magazine needed a new high space for Jeffrey Katzenberg when his partnership with Spielberg and Geffen was announced). And after several last-minute calls from Margaret Wade—who insisted it would be “insulting” for Morgado to share a ranking with his subordinate—the list that went to press had Morgado alone at No. 19. Doug Morris wasn’t on it at all, even though Jimmy Iovine and Ted Field. Danny Goldberg, Lenny Waronker. Sylvia Rhone, and even Dr. Dre were.

Wade says she had no idea that her efforts would result in Morris’s not being on the list. E.W. managing editor Jim Seymour Jr. agrees that she couldn’t have known—nor could Morris’s publicist have known that the magazine owed Morgado the benefit of any doubts because of a factual error in his 1993 listing. “Finally it’s about midnight,” says Seymour, “and we’ve had several more objections from Margaret Wade. I finally said, ‘Take him the hell off the list and get this closed.’ and that’s what happened. I made a mistake taking him off—Morris deserved to be on the list, but I had to get the issue closed .… It was only after the fact that we found out about this little hornet’s nest at Warner.”

The buzzing grew more intense as word came from Burbank that Lenny Waronker was absolutely miserable in his new job. Rumors were floating that his problem was mostly pressure from Morgado to lay people off. But Waronker insists that wasn’t the case: he had even called Morgado earlier in the month and unloaded all his fears and unhappiness about the new position. “My stomach changed my mind,” he says, slouching in a chair in his office. “I wasn’t feeling particularly good. I was struggling to get up in the morning. I can give you some metaphors for this, but, in the studio, when something doesn’t feel right, you either fix it or get rid of it.”

It was only a matter of time before Waronker would announce that he wasn’t taking Mo’s job after all. which looked very bad for Morris and Morgado. Doug Morris had to start thinking about who could replace him at the Warner’s helm. One of his suggestions was 44-year-old Rob Dickins. Warner Music’s attitudinal U.K. chairman, who had long-standing relationships with many of the artists, especially Rod Stewart. Dickins was, by his own admission, “not an easy lunch.” and Morris was apparently concerned about his personality, which they discussed when Dickins was called in while in New York scouting an act. “Doug said I was arrogant and imperious.” Dickins recalls. “Doug has a thing about arrogance. He said, ‘You know, you’ll have to change.’ He also told me that Danny Goldberg was sarcastic when he started at Atlantic but ‘we had to change that.’

“When he talked about the job, he didn’t make it terribly attractive. He wanted to run Warner Bros., and he wanted me to be a label manager. I said in my past experience the company didn’t run like that. He wanted joint appointments of any key executives, reporting in every single day. It’s Atlantification. isn’t it? .… Here I was being offered my dream job. but it was no longer the way I dreamed it would be: I have a feeling that’s what Lenny felt when he got to the same door … but when Morris said, “I’ll probably offer you this job—what will your reply be?.’ I said. ‘I’ll probably accept.’ ”

Dickins flew to L.A., where he had lunch with Danny Goldberg. “He told me. ‘Doug is the brightest executive .… It was like a P.R. job to me, and he did a very good job of it.” says Dickins. “Not long after the lunch. Doug called and said he still had a few things to work out. but things were looking good.” Then Lenny Waronker made his decision known internally, and news of it leaked to the Los Angeles Times. The Warner Bros, artist roster let out a collective scream, because Lenny was their beloved touchstone.

R.E.M., who had the No. 1 album in the country with Monster, a reputation for activism, and only one record left on their contract, made noises that they would leave with Lenny. The gossip mill immediately had Lenny going with Mo to run the music division of the Geffen-Spielberg-Katzenberg venture, which had been announced as a stand-alone company but was starting to be talked about as a ploy to get control of an existing studio and distribution system—possibly the one at MCA. where Geffen had his record deal and was helping Bob Krasnow set up one of his own. And the press began speculating about a revolt of the Warner’s artists. While a number of journalists pretended not to know that most artists had long-term contracts and couldn’t leave Warner’s if they wanted to, they were accurately reporting the outrage of some of the biggest names in popular music.

“Please don’t use my name,” says one Warner’s executive, “but I’ll tell you. Neil Young is not happy. Eric Clapton is not happy, K. D. lang is not happy. They’re in turmoil.” Paul Simon’s spokesman says. “He is very unhappy.” There was endless speculation about who had a “key-man” clause in their contract, which would allow them to leave with Mo. “If artists were able to leave,” says the manager of one of Warner’s top acts, “there would have been a line out to the Oyster Bar.” Flea, from the Red Hot Chili Peppers, was so upset that he later wrote a mournful “Song for Mo” (sample lyric: “Mo. Mo / Why do you have to go? … Warner Bros, will never be the same. / I want to thank you for all the Laker games”) and sent him a tape of it.

Dickins hung around L.A. for a few days. When he didn’t hear again from Doug Morris, he decided to go back to the U.K. He couldn’t figure out exactly what was going on, which isn’t surprising, since to this day it is still a little unclear just how the situation between Morris and Morgado reached supernova heat. There was obviously a disagreement between the two men over which of Morgado’s responsibilities had been passed down to his new U.S. labels chief. But mostly it was a 54-year-old record man and his 51-year-old corporate boss—who together had just pushed out all their Music Group detractors—playing what one company executive described as “a big game of chicken.”

Morgado portrays Morris’s situation as similar to Waronker’s. “Doug was saving, ‘Bob, I don’t know if I can do this job: maybe I should so back to Atlantic.’” Morgado recalls. “Life was more wonderful back in the Atlantic days. He didn’t have so many things to worry about then. Now the Lenny thing was in the paper, all the artists were going to leave .… I told him I thought the new job was a natural evolution of his career … but he needed to come to terms with himself.”

One Music Group source portrays the situation very differently. “Morgado didn’t want to give any power up to Doug.” he says. “It was a blatant thing of giving Doug a job and taking it away, the arrogant assumption that he would take a title with no power and substance. It was a bitter, hostile war that had nothing to do with any misunderstandings: Morgado lied. He was a corporate guy with a personal desire for power, and he was having a tantrum.” (He had also earned himself a nickname: the Lyin Hawaiian.) Morgado couched the dispute more in terms of “I had to disengage a little bit, giving him a greater sense of comfort in his dealing with the U.S. labels, and he had to learn to step back from being a label head and be more of a group manager.”

On October 26. Morgado made a presentation to Wall Street analysts about the future of Warner Music. Morris was apparently angered that he was not invited, and that the contribution of the U.S. labels—whose artists accounted for nearly half of the Music Group’s world revenues—didn’t get enough attention. That afternoon Morgado and Morris had a meeting with Time Warner C.E.O. Jerry Levin. Rather than mediating the situation. Levin left after five minutes and told the two to settle the matter themselves. They couldn’t, and according to several sources, they had a shouting match.

Later that evening, Morgado called Morris at home and told him he would be going back to Atlantic. Whether this meant Morris had been fired or Morgado had just granted him his wish depends on who’s doing the spinning. Not long after. Morgado called Rob Dickins. There are various spins concerning where Dickins’s candidacy stood before the call: some say Morris had already decided against him: some say he was still considered viable. What is not in dispute is that Morgado told Dickins he had the job.

“It was the middle of the night, and Bob said he and Jerry had had a meeting, and they wanted me to fly in immediately.” Dickins recalls. He was especially pleased by the way Morgado was now describing the position. “Bob said to me. ‘I’ve now realized that Warner Bros, is a different independent spirit from what I thought it should have been. I now realize we’re in danger of having one big company, and you’re the person who carries the culture.’ I think he finally realized he had been blinded by Atlantic’s success .… Bob realized the danger of the Atlantification of Warner Bros. Records.” Morgado called Morris again at about midnight to tell him Dickins had been appointed to replace Lenny.

By the time Dickins got to New York and checked into his room at the Carlyle Hotel, all of Morris’s top executives had gathered at the Central Park West apartment of Stuart Hersh, who runs Atlantic’s video arm. There were 10 of them in all, including Ahmet Ertegün, and nobody was certain if they were there to celebrate or sit shivah. “I was as nervous as a fucking cat.” says one of the participants. Morris was supposed to join them, but he had been called in to meet with Morgado again.

“It was an extreme confrontation,” says one Warner Music source. “Demoting Doug was a way of saying ‘Fuck you.’ … This was not about soul-searching. This was Doug saying. ‘Listen, you piece of shit, if you’re going to renege on promises, I’m going to make you look like an asshole.’”

Dickins was caught in the cross fire, as he learned when he called Morgado from the hotel. The fight wasn’t necessarily over whether Dickins was the right guy for the job but over who had the right to make the hire: Morgado or Morris. Dickins couldn’t believe what was happening. Every major player on the team that Morris had put in place had, over the past day or two, called Jerry Levin to express support for Doug: the implicit understanding was that they were prepared, if not to resign together, then at least to be very disgruntled together. Ertegün had even called Mo Ostin to see if he wanted to come back and join the rebellion, but Mo had declined.

Many would come to see this as the ultimate battle between “record people” and “the man.” Dickins, of course, saw it differently. “These Atlantic people are like a cult in a way, aren’t they?” he says. “It’s the ultimate sacrifice: are you willing to give up your job to stop Bob Morgado in what he wants to do to our team?” While this was happening, Dickins was just sitting expectantly in his hotel room.

Morris left his meeting with Morgado, went to Stuart Hersh’s apartment, and then returned to his office. Sometime that afternoon, various forces conspired to make peace. Some published reports have said that Jerry Levin forced Morgado to give in to Morris after several Time Warner board members called him upset about all the negative press. Levin has declined to comment on the situation, but a source close to him says that even though he did have several conversations with Morgado during the two-day period, “this was not tight-reined management.” The source says rumors about board pressure are “completely untrue.”

Ahmet Ertegün says he was the final peacemaker. “Obviously there was a lot of bad blood and anger.” he says, “but it was based on nonsense. After Doug’s meeting in the morning was not fruitful. I called Bob. Within an hour they had a meeting and resolved everything.” Morgado issued a press release which referred to Morris by a new title: instead of president of the Music Group, he was now chairman and C.E.O. And Rob Dickins was screwed. Morgado called to tell him. In the limo to the airport the next morning, he got a call informing him of Morris’s choice to head Warner Bros.

“I kiss the feet of talent … and other parts of their anatomy. I’m commited to that as a strategy.”

The idea had come to Morris during the heat of the battle the day before. The perfect candidate for the job had been right under his nose the whole time. It was the same person who, six months earlier, had been the perfect candidate to fill Morris’s old job. It was Danny Goldberg, who had just uprooted his family from California—including his wife’s successful entertainment-law practice—to move to New York to take over Atlantic. The 42-year-old music wonk, who had been respected as a manager, but had been a record executive, as even his fans noted, for only about two years, was going to be the new Mo Ostin.

Rob Dickins was left dazed and confused. “I don’t get it,” he says. “If Danny was the right person to run Warner Bros. Doug had an absolute right to take him. But why even bother to duck up Rob Dickins’s life at all? He had a perfectly good life. Why do that to Rob Dickins?

“This has all been like Invasion of the Body Snatchers. You went to bed. and you wake up the next morning and everyone is from Atlantic Records. The whole beauty of the Warner Music Group was that, as an artist or a fan, you had cutting-edge, interesting Elektra to go to, hard-nosed Atlantic to go to, or artist-friendly Warner to go to. We had a redhead, a brunette, and a blonde. And we just shot the redhead and the blonde.”

Danny Goldberg sighs, takes a deep breath, picks up the phone in the Time Warner Building office he will soon be vacating for a much better one in L.A. and begins yet another session of the rock ‘n’ roll phone sex that goes along with his new new job. Goldberg once told Billboard that the secret of his success was “I kiss the feet of talent … and other parts of their anatomy. I’m commited to that as a strategy.” Now he’s getting a chance to put his mouth where his money is.

As the head of Warner Bros. Records—and still the official spokesman for Doug Morris—Goldberg is now the one who has to reassure everyone in the skittish Warner’s world that somehow life can go on. The low- and mid-level employees get well-written, self-effacing memos. But, for the big names on the W.B. roster. Goldberg is still committed to his time-honored strategy: he is quickly, contritely, and professionally puckering up for each one of them.

As he sits in his office discussing the fall of Warner Music’s discontent, legendary staff producer Ted Templeman’s name appears in the blue digital readout device his secretary uses to let him know who’s on the phone. Goldberg takes the call. He tells Templeman he has been a longtime admirer and is very eager to figure out how he’ll be involved at the label. He says he probably ownsall the albums Templeman has produced. At the end of one sentence, he says “man.” which is how music people still communicate solidarity with other music people.

When the brief call ends—one more down, untold dozens left to go—Goldberg picks up where he left off. His theme is that the worst is over, the company’s family feuds are behind it, and damage is controlled. His message is that the final curtain has come down on “the Play.”

Yet news continues to come from the wings. Goldberg helped to stabilize Warner Bros, by getting several of Mo’s top people, such as new vice chairman Russ Thyret, to sign new contracts. The Metallica lawsuit got settled, after Morris was forced to offer a deal even better than the one rejected as preposterous six months earlier; the final deal was drafted just after Morris and Morgado had given depositions to Metallica’s lawyers. Sire’s Seymour Stein was named president of the newly formed Elektra Entertainment Group. His boss Sylvia Rhone’s first move was to buy Elektra a stake in the independent Seattle label Sub Pop, which had discovered, and lost, to major labels many of the great grunge bands, from Nirvana on down.

Bob Krakow announced his five-year deal with MCA, suggesting that some of his Elektra acts would eventually join him there. David Geffen can leave the record company he sold to MCA in April to start another within his new studio: Mo will apparently be free by June to join him, and so will Lenny by the end of the year. When Krasnow was asked where Geffen’s new record company might be based, he replied. “All I can say is. MCA is the place to be.”

Morgado so far seems secure internally. “My bet is, Morgado wins,” says one former Music Group executive. “The guy who should be nervous is Doug Morris,” says the manager of one top Warner act. “He has a guy above him he went to war with but is not dead, and he has a guy beneath him. Danny Goldberg, who he might look at as his guy, but-boy oh boy.”

Final curtain? Most people watching the Warner Music Group believe that this is only the intermission.