I didn’t want to be part of anything when I was a teenager, especially my family. There were seven of us, and they pressed in on me. So I buried my head in books. My reading irritated my parents; books were a narcotic I used right in front of them. I was disengaged, dissipated. I tripped into the 19th century or early Rome while my four younger siblings swirled around me, background noise. Once in a while, it would quiet down. One of the kids would disappear on a sleepover, and that was such a relief. If only there were fewer of us, I used to think. I really remember thinking this, and it’s significant, because one twilight in spring when I was 16, one of us disappeared for good.

I was out for the night at my high school’s annual Latin banquet, buying a freshman slave at auction and amusing myself by having him roll a grape around the cafeteria. My parents were barbecuing shish kebabs in front of the old farmhouse we lived in. My sisters were playing softball in the side yard, by the lilac bushes. The younger of the boys were chasing cats, and the older, David, who was eight, was agitating to run across the road. He wanted to show his friend Theo his new wristwatch, a present for making his first Holy Communion that morning. At the end of the driveway, we guessed later, he checked for traffic both ways, then waited for the second hand to finish its sweep to the top of the minute, so he could time his dash across the road. It took forever.

I wish I could remember us a little better, a regular family in Ohio, a dad who commuted, a mom who made meat loaf, brothers and sisters who played Ping-Pong. I remember sitting in the backseat of our station wagon, yelling because one bumped me. I made a rule: Nobody could touch anybody. Now that I have children, I see how impossible it is to prevent kids from crawling all over any thing or body in their path, hitting, hugging, licking, jostling. I feel different now about being touched. Back then, I worked hard to keep kids off me.

And suddenly one of the kids was, as the priest said, lifted up into heaven. We lived in a town of 4,000 people, where a little boy’s death is big news, so for a while we were famous. We were bathed in a spotlight of attention. I felt important, weighted down with the tragedy. I was self-conscious, I, who had lost a brother. The others were weepy, and I fought that as I fought every natural emotion. I kept my chin up. I saw myself as the one who kept things going, but I was just procrastinating.

One afternoon, months after my brother’s death, I took the bus home from the high school. As we pulled into the lot of the parochial school to pick up the little kids, I saw him dashing across the pavement. David, I thought automatically, with a sweet twinge of recognition. And then I realized it couldn’t be him, not ever. That was what he had become. An absence. The one whose place I didn’t set at the table. The one I would never see again.

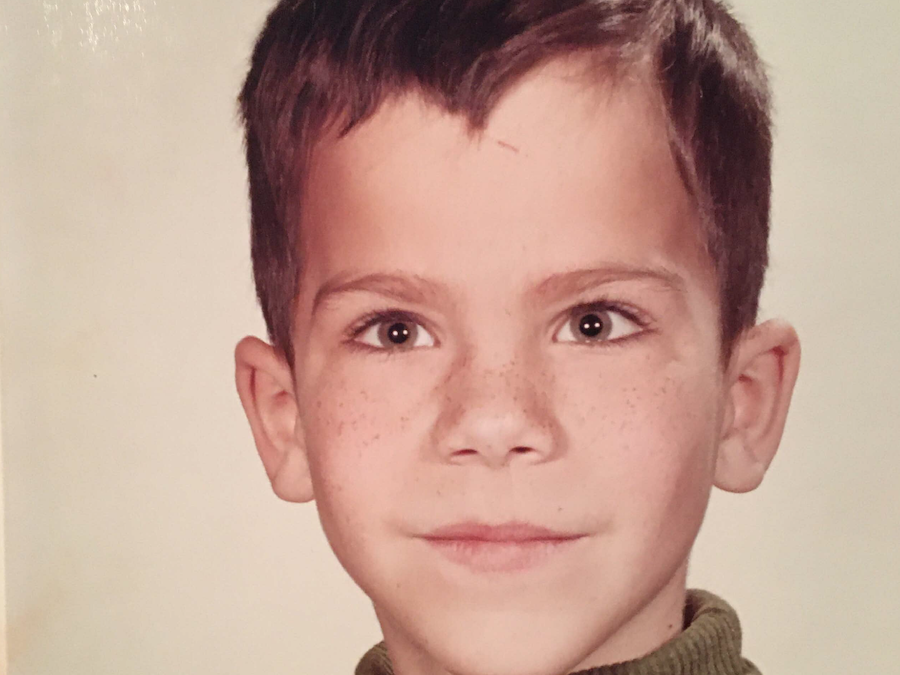

Twenty-one years might be enough time to lose that rawness of feeling, but it took a good chunk of that to be able to say my brother died without my stomach dropping. We are all so much older now; now he, an eternal eight-year-old, is closer in age to his nieces and nephews than to us. Now he’s a photo we have to identify.

I was driving my little boy through town one day when a child about David’s age dashed in front of my car, racing to his mother across the street. I stomped on the brakes and missed him by less than a foot. The mother looked at me as the horror hit both of us; then she grabbed her son and began slapping at him. Fear. I started to drive away, but my body wouldn’t work. I had to pull over to the side of the road and cry. And then I had to explain to my son why I was crying.