“You’re here,” Eddy Jo said.

“Just barely,” Teri Shields said. She made a motion as if to sneeze, then caught herself.

“I was wondering,” Eddy Jo said. She carried three spiral notebooks, cradled in her arms like a fat baby. She wore a white-vinyl jacket with CIRCUS OF THE STARS written on it, and she had a blonde hairdo that fit her head like a batting helmet.

“The plane landed about an hour ago,” Teri said. She was a plump woman, dressed in an oversize faded-khaki shirt and blue jeans. “Brooke’s dressing now. You don’t have a Kleenex, do you?”

Eddy Jo shook her head.

“I think I’m allergic,” Teri said, pinching her nose. “All these animals around.”

A few feet away, an orangutan perched on a folding chair. It was attended by a Nordic-looking young man in a tuxedo. The orangutan wore a red tutu and held the young man’s hand, with a satisfied smirk on its face.

“So?” Eddy Jo said. “What’s new?”

“It’s been a long day,” Teri said. “Brooke had to go into Manhattan this morning to loop the dialogue for her movie of the week.”

“She did a movie of the week this morning?”

“Looped the dialogue,” Teri said. “It’s a cute movie, I think. We only saw a black-and-white print for the looping.”

“But it’s cute,” Eddy Jo said. “That’s good.”

“Then we got on the plane, flew here, got the limousine, got to the hotel—I’m not even sure what time it is.” She checked her watch. “Brooke did her homework on the plane, while she was watching The Terminator for the fourth time.”

“It’s the desert,” Eddy Jo said.

“What’s that?” Teri said.

“Las Vegas. The desert. That’s why you’re allergic.”

“I think it’s the animals,” Teri said. She looked at the orangutan, which was now holding a banana. It grinned back furiously, displaying the half-peeled fruit as if it were a sexual device.

“Monkeys,” Eddy Jo sniffed.

A man approached them, carrying an assortment of combs and brushes, a can of hair spray and a box of tissues. His hair was cut as closely as a putting green.

“Brooke’s just getting dressed,” Teri told him.

“I saw her,” he said. He didn’t look happy. “Her coif is falling. Tomorrow we’re going to have to keep her hair up. Way, way up. All day long.”

Teri took a handful of tissues from the box, turned her head and sneezed.

“Bless you,” the hairdresser said. “For now, we’ll have to do, I don’t know….” He looked at the can of spray and shot off a fine mist. “Something.”

Teri looked at her watch again. She shook it and held it up to her ear. Eddy Jo rocked her spiral notebooks as if the baby were waking up.

“So you’re going to start taking it easy,” Eddy Jo said.

Teri looked at her in surprise. “I’m not taking it easy,” she said. “What are you talking about?”

“On the phone,” Eddy Jo said. “You told me you’d been talking to William Morris. I thought you were going to relax a little, you know. Not do so much.”

“William Morris?” Teri said, shocked. “William Morris manage Brooke?”

“Well, I just thought,” Eddy Jo said.

Teri started to laugh so hard she had to beat her chest with her hand.

“God help us,” she said. “William Morris.” She dabbed at the corners of her eyes with a tissue. “No, that was a movie they were talking about. This will grab you, Eddy Jo. They wanted her to play Pocahontas.”

“Pocahontas?” Eddy Jo said. She tilted her head to one side. “Who do you mean, the Indian?”

“Yeah, can you see that? Miss Blue Eyes? With feathers?”

“Different,” Eddy Jo said.

“That’s why they’re not handling her career,” Teri said. “Here comes the Indian princess now.”

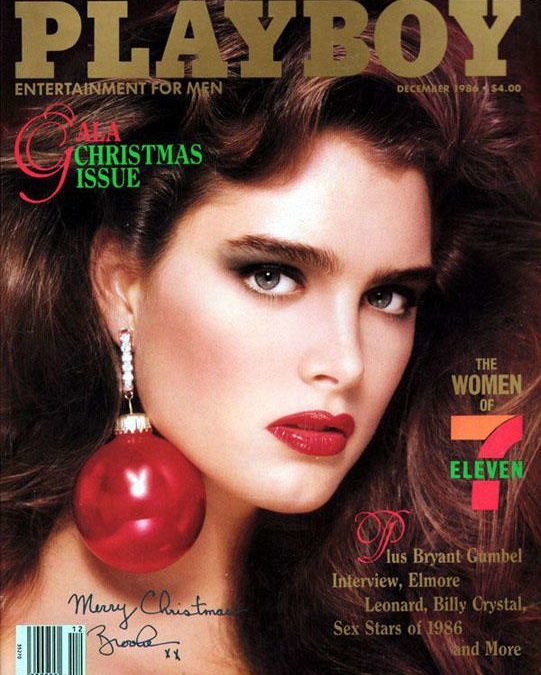

Brooke Shields emerged from a dressing trailer parked next to a red-and-white circus tent. She was dressed in a red-sequined ringmistress jacket, a high-cut black leotard, fish-net stockings and four-inch black heels. She was escorted by a muscular bodyguard wearing a copper-colored suit.

“How do I look, Mom?” Brooke said. She held a green apple in her hand.

“You look good,” Teri said. She took a lock of Brooke’s hair and held it up as if she were inspecting for traces of white fly.

“They’re waiting for you to get made up,” Teri said.

Brooke took a bite of her apple and nodded.

“He’ll do something with your hair.”

Eddy Jo watched Brooke walk away and said, “God, she’s tall.”

“And she’s not getting any shorter,” Teri said.

“She’s doing an act?” Eddy Jo asked.

“Well, she was just supposed to host,” Teri said. “But she’s done an act every year, so it would seem like, you know….”

“A disappointment?”

“I guess.”

“Is that what they said?”

“Something like that. So she’s going to do this thing, this glass walk.”

“What’s that?” Eddy Jo said. “She’s going to walk on glass?”

“Broken glass,” Teri said. “Broken Dr Pepper bottles; that’s what the man told me. He’s some sort of specialist at this. He says that Dr Pepper bottles make a better crunching sound underfoot.”

“Gosh,” Eddy Jo said. “I mean, broken glass.” She had to stop and think about it. “Isn’t that dangerous?”

Teri shrugged lightly.

“They say it really isn’t,” she said. “They say if you put enough glass down, it’s like a level surface.”

She made a flat-handed motion in the air. “That’s what they say, anyway. Here’s the costume she’s wearing.”

A wardrobe girl came up holding a gold, jeweled harem outfit that looked like it came from a college production of Kismet.

“Very different,” Eddy Jo said.

“Put it in the trailer,” Teri said. “It’s the one with no hot water and no toilet paper.”

She looked at Eddy Jo and smiled faintly.

“Maybe William Morris could help after all.”

Merv Griffin, wearing a tuxedo with sequined lapels, his face thick with make-up, put an arm around Brooke Shields’s waist and looked up into her eyes.

“How’s the weather up there?” he asked.

There was an explosion from a strobe light and a voice said, “Love it!”

Griffin stepped aside and his place was taken by Emmanuel Lewis.

“Better get a chair for him to stand on,” someone said.

“A chair? Better get a ladder,” someone else said.

“Never mind,” Brooke said. She reached down and effortlessly scooped Emmanuel up into her arms. The little black boy put one arm around her neck and smiled brilliantly.

A mocha-skinned photographer, sporting riding breeches and highly polished knee-high boots, shot off a burst on his Nikon. “That’s cool,” he said.

Teri stood a few feet away, watching Brooke on the photo stand. “I feel like I’m about to drop,” she said.

The bodyguard, sitting in a folding chair with his arms crossed, got to his feet.

“Teri, please,” he said. “Sit.”

“He doesn’t look all that big for a bodyguard,” Eddy Jo said under her breath.

“He carries a gun,” Teri said, sinking wearily onto the chair. “He’s big enough.”

A bearded man who looked like he could be John Huston’s younger brother came over. He was also wearing a CIRCUS OF THE STARS jacket and was smoking a pipe.

“You going to stay out here for a few days?” he said to Teri. “Take it easy?”

“Everybody wants me to take it easy all of a sudden,” Teri said. “No, we’re going back tomorrow night. Brooke has to be in school on Monday.”

“School,” the man said. “Jesus, she goes to school; that’s right.”

“Yeah, I’m trying to get reservations now, but everybody’s full out of Las Vegas.”

“Why don’t you fly that ritzy airline? The hell’s the name of it?”

“Regent,” Teri said. “They don’t fly out of here. We’ll have to catch a late flight out of Los Angeles that’ll get us to New York about six in the morning. Then a helicopter will pick Brooke up and take her back to Princeton.”

“She did her homework on the plane,” Eddy Jo said to the bearded man.

“I’ll be goddamned,” he said.

Teri caught Brooke’s eye and made a head-raising motion. Brooke looked back, closed her eyes and dropped her chin to her chest.

“Only thirty-six more, Teri,” one of the photographers said.

“Oh, great. Only thirty-six.”

Eddy Jo bent over and spoke quietly into Teri’s ear. “There are some kids who’ve been waiting to see Brooke,” she said. “I don’t know if you can fit it in.”

She gestured with her head across the room. A young mother and father waited patiently with their three little children, all asleep on their feet, each holding a balloon and an autograph book.

“They’ve been waiting since six o’clock,” Eddy Jo said.

“Six o’clock?” Teri said. “God, that’s six hours.”

“I can deal with it if you want me to,” Eddy Jo said.

Brooke stepped down from the photo stand and took off her high heels. “I want to go to sleep,” she said.

“In a minute,” Teri said. “There’s something I want you to do first.”

She led Brooke over to where the children were waiting. They watched with expressions of awe, as if they were seeing a vision.

“This is such a thrill!” their mother said as Brooke signed each of the children’s books. “They just adore you!”

“Take a picture if you want,” Teri said to the father. “Brooke, get in there in back of them.”

Brooke bent her knees and dipped down, posing herself in back of the children like they were all a singing group. The youngest, a curly-headed, dimpled girl, regarded Brooke with solemn eyes.

“You have to smile if you’re going to have your picture taken,” Brooke told her.

The little girl’s eyes became darker. She seemed ready to cry.

“Ohhh,” Brooke said. “Are you sleepy?”

The little girl moved her head up and down slowly.

“Me, too,” Brooke said. “It’s past my bedtime. Let’s just smile big one time, then go to sleep. Good idea?”

The little girl’s face brightened suddenly, like the passing of a summer storm. She broke into a big, wide grin, threw her arms around Brooke and gave her a kiss. The flash on her father’s camera went off with a tiny pop.

“This was so nice of you,” the mother said to Teri. “I can’t thank you enough.”

“We run a magic shop on the Strip,” the father said, taking a business card from his shirt pocket. “I’d really like Brooke to come in sometime. Pick anything she wants. Does Brooke like magic?”

“She did a special with Doug Henning,” Teri said. “As a matter of fact, she’s going to do a walk over a six-foot runway of broken glass tomorrow.”

The mother cringed. “Real glass?” she asked.

“Oh, yes,” Teri said. “Real glass. Dr Pepper bottles.”

“That sounds so scary,” the mother said.

“They say it isn’t,” Teri said. “They say if you put enough glass down, it’s like a level surface. Isn’t that right, Brooke?”

Brooke looked at her mother sleepily. Then she smiled a skeptical smile and said, “That’s what they say.”

“Listen to this,” Teri said. “‘Who have you been dating lately?’ ”

“That’s direct,” Brooke said. She was seated at a make-up table, wearing white jeans and a black T-shirt. Her hair was up in white-plastic curlers.

Teri sat on the other side of the narrow, sparsely furnished dressing room, reading from some typewritten pages.

“This is The Tonight Show, Brooke,” Teri said. “They want the nitty-gritty.” She read on. “It says, ‘I understand you’ve been seeing Alain Delon’s son.’ Did you hear that, Brooke? That’s terrible.”

Brooke leaned toward the mirror, applying eye shadow. “What’s that?” she said.

“They refer to Anthony as Alain Delon’s son. Isn’t that terrible? They don’t even use his name.”

“Oh,” Brooke said. “His feelings would be really hurt.”

Teri took a pencil out of her shirt pocket and made a note on the page. “I’m going to have them change that. I don’t like that.”

“No, that’s awful. He’d feel very bad. That would be embarrassing.”

There was a knock at the door and a young man entered, wearing sharkskin pants and a navy-blue tunic shirt.

“I found the dress,” he announced. “It’s red. It’s gorgeous.”

“Did you bring it?” Brooke asked.

“It’s upstairs. You’ll flip.”

“How much was it, Warner?” Teri asked.

Warner made a motion of indifference.

“Bob Hope has the money,” he said. “Besides, I told them it was perfect, that they’ll die when they see her in it, so what do they want? How can you put a price on glamor?”

“They can put a price on anything,” Teri said.

Warner sat down on the couch and took an orange from a basket of fruit.

“You look divine,” he said to Brooke.

She looked at herself in the mirror, at her half-made-up face.

“Uh-huh,” she said.

Teri looked back at the script. “‘So, Brooke, you’re writing a book. What’s that all about?’ Brooke answers that it’s to help make the transition from high school to college, da, da, da….”

She flipped the page.

“What’s that?” Warner said, peeling the orange.

“It’s the script for Brooke’s interview.”

“They write all the questions and answers down? Ahead of time?”

“That just gives them an idea,” Brooke said, applying mascara to her eyelash. “It makes them feel better.”

“How bizarre,” Warner said.

“‘How’s school?’“ Teri read. “Brookie, how’s school?”

“Fine; I think I might flunk out, thank you for asking.”

“Really, Teri,” Warner said, putting a section of the orange into his mouth. “Wait until you see this dress. She’ll look so fabulous, it’ll make the whole show.”

“Oh, do you know what they did, Warner? They called and told me they had a wonderful surprise for Brooke. Listen to this wonderful surprise. This was going to be a big favor because they like Brooke so much.”

“Sounds like trouble,” Warner said.

“They wanted Brooke to call up Michael and have him do a black-out with her on the show.”

“No!” Warner said, looking incredulous. “Seriously?”

“Can you believe the nerve? This is, mind you, one day before the show tapes. How it was going to be a surprise if she had to arrange it, I don’t know.”

“They must be hallucinating,” Warner said.

“That’s what I told them. This is also the very same day that Michael, the biggest star in the world, is appearing before 50,000 people at Dodger Stadium. And they want Brooke—because they like her so much, because she is such a great kid—to talk him into casually running out to Burbank to do a black-out on the Bob Hope Christmas show.”

“They’re classy people,” Warner said. “No doubt about it.”

“They said, ‘Well, we thought they were friends.’ I said, ‘You obviously don’t know anything about friendship. A friend does not take advantage of a friend that way.’ I mean, really. This shows no respect for Brooke, no respect for Michael….” She counted these offenses off on her fingers.

“And here’s the part you’ll love. After I told them that I absolutely didn’t want to discuss it, not to even mention it, they said, ‘Well, we could get Michael Jackson if we wanted. That’s not the problem.’ ”

“Ha, ha, ha, ha,” Warner said. “Right.”

“Yeah,” Teri said. “I told them, ‘Fine, go ahead.’ ”

She stood up and put her glasses on top of her head. “I have to go talk to them about this,” she said, holding up the script.

“Please do,” Brooke said. “I’d hate to hurt Anthony’s feelings.”

“Did you speak to Joan Rivers?” Teri asked.

“Just for a minute.”

“Did you ask about her husband?”

Brooke nodded. “He’s feeling better,” she said.

“OK, you better hurry up. I’ll see you upstairs.”

“I saw you on Circus of the Stars, Brooke,” Warner said, separating another section of orange. “You were super.”

“I don’t know,” Brooke said. “I was pretty tired that weekend.”

“And that act; that was such a panic. What happened to your foot?”

“Oh, it was just a little scratch. It wasn’t a big deal.”

“They showed a big close-up of your foot. There was blood. They showed you bleeding.”

“Yeah …” Brooke said. “But it wasn’t a big deal. I did it twice, on two different days. The second time, nothing happened at all, but they used the first one. I guess they wanted to make it more exciting.” She yawned.

“Brooke Shields draws blood!” he said, as if quoting a newspaper headline. “I think they were gasping all across the country.”

She looked in the mirror, the white-plastic curlers in her hair. “If they saw this,” she said, “they’d really gasp all across the country.”

The door flew open and a man dressed in brown corduroy came in.

“Brooke, Brooke, Brooke,” the man said. He held a rolled-up sheet of paper in his hand and tapped it against his leg.

“Everything OK? You got everything?”

“Fine,” Brooke said.

“You got the questions, the script? Go over all that?”

“Yes,” Brooke said. “Well, as a matter of fact—”

“Great,” the man said. “Super.” He looked around the room as if he were thinking of buying it.

“Just have fun, right? That’s it, right?”

“Right.”

“OK, listen, one thing.” He brought the paper forward like a shifty landlord. “We want you to do this one bit, a promo for Joan’s special. Five seconds. We’ll tape it after the show.”

Brooke took the piece of paper and looked at it. “I’m doing this now?”

“Right after the show. Five seconds. We’ll have cards.” The man looked around the room one more time. “Great,” he said. “Beautiful. You want this door closed?”

“Please.” Brooke stared after the man in mild wonder.

One second later, the door sprang open again and the man stuck his head back into the room. “Listen,” he said, “I saw you cut your foot. Wow!”

“I’ve got rhythm,” the chubby young man said. “I’ve got speed. That’s my secret.”

The other photographers, six of them, didn’t say anything. They stood around restlessly in the narrow corridor, like expectant fathers.

“I’ll be changing lenses in mid-shot. All you’ll see is a blur.”

A beak-faced man wearing a golf hat with an NBC pass stuck into its brim said, “How come they let you in, Norman?”

“How come they let you in, Hoos Foos?” Norman said. He was bursting out of a pale-gray lightweight suit, and he wore dove-gray Capezio jazz shoes. He did a couple of steps on the linoleum floor.

“You have to be smooth to get in here,” he said. “You have to have moves.”

“Your hat’s on fire,” the beak-faced man said, waving his hand at him.

The double studio doors opened suddenly. “Here she comes,” Norman said.

The photographers came alive as Brooke stepped into the hall, carrying a bouquet of flowers. Warner walked alongside her, holding aloft a long red evening gown in a plastic dry cleaner’s bag.

“Brooke! Brooke! Brooke!” They all began to shout together. “Brooke, this way! Brooke, over here!”

There was a barrage of shutters and power winders. The whirring motors sounded like a swarm of android hornets.

As Brooke stepped forward, automatic flashes exploded in her face like the finale of a laser light show. She came to a stand-still as the photographers pressed in around her from all sides.

“All right, gentlemen,” Teri said, striding into the scene. “Let’s have a little room to breathe. I’m not wrong in using the word gentlemen, am I?”

A nervous-looking young woman stood at Teri’s side. “I guess this is a bad time to talk to you.”

“No, this is a normal time,” Teri said. She watched as the photographers continued their rapid-fire assault.

“My smile muscles are hurting,” Brooke said to Warner out of the side of her mouth.

“If we could just set this up for tomorrow,” the nervous young woman said. “I promise it won’t take any time at all. We can do it anywhere you say.”

“Tomorrow …” Teri said, thinking about it.

“Absolutely no time at all,” the young woman said. Her eyes blinked rapidly. Her hands made little motions in the air.

“Tomorrow we have to go to a hospital in Downey,” Teri said. “Do you know where Downey is?”

The young woman shook her head.

“We’re going to visit a hospital there,” Teri said. “Terminally ill patients, mostly children. They’re having celebrities come out for Christmas.”

“Oh, my,” the young woman said, her hand covering her mouth. “Oh, how sad.”

“Yes,” Teri said.

Brooke turned around and gave her mother a look of open-eyed disbelief. Apparently the photographers had an endless supply of film.

“OK, here’s what we can do,” Teri said. “We’ll be going from the hospital to the airport. We should get there about one-thirty. The plane leaves at two. You can meet us there.”

“Perfect,” the young woman said.

“It’s Regent Air; it’s not part of the main airport. You’ll have to find out where it is.”

“No problem,” the young woman said. “This is just so—I can’t even tell you how—” She took a deep breath.

“I understand,” Teri said.

“Just a few short questions about school and boys, things like that. And how she feels about being selected America’s Dream Date.”

“Mom,” Brooke said, looking over her shoulder again.

“We have to go,” Teri said. “See you tomorrow.”

She took Brooke by the arm and moved her along the hallway. The photographers backed up in front of them, still shooting.

“What was that?” Brooke asked.

“You’re America’s Dream Date,” Teri said.

They moved toward a spacious area with vending machines and large open doors leading to the parking lot.

“I have to get popcorn,” Brooke said, pointing to one of the vending machines. “Do you have change?”

Teri patted her pockets.

“Never mind. Here.” Brooke handed the bouquet to Teri. She took a white-leather bag off her shoulder, balanced it on one knee and began looking through it.

Teri turned to the photographers and said, “All right, that’s enough for tonight. Thank you all, but enough is enough.”

The chubby young man in the gray suit appeared next to her.

“Norman,” she said, looking at him over her glasses, “the session is over. Didn’t I say that?”

“I hear you,” Norman said. “Hey, Brooke, great act on Circus!” he called to her. He looked at Warner. “Nice dress.”

“So good night, Norman,” Teri said.

“Look, I’m leaving right now.” He pointed to the doors. “My car’s out there, through there somewhere.”

“That’s the parking lot. That’s where our car is. That’s off limits to you.”

“And I respect that,” Norman said. A ring of perspiration appeared at his hair-line and he took a handkerchief out of the breast pocket of his jacket.

“Really?” Teri said. “Like the time you respected the hotel garage?”

“What garage?” Norman said, mopping his face. “Did you say a garage?”

“The one with the security gates. The one you broke into.”

“That must have been the night of the Golden Globes,” Norman said, smiling fondly. “OK, maybe I broke in—you said broke in, I didn’t—but, hey, I was polite, wasn’t I?”

“You ambushed us in an elevator.”

“I was never in the elevator,” Norman said, holding the handkerchief up for emphasis. “At no time. I was maybe in the elevator lobby, that’s all.”

Teri sighed.

“They were great pictures, though, weren’t they?” Norman said. “Admit it.”

“They were OK,” Teri said, shrugging. She watched Brooke, a few feet away, put coins into the popcorn machine.

“OK? They were great! That killer Cosmo top she was wearing? ¡Ay chihuahua!”

Brooke pressed the buttons on the machine and waited. Nothing happened.

“Kick it, is what I usually do,” Norman said in a raised voice.

“Good night, Norman,” Teri said.

Norman walked over to the machine, his canvas camera bags bouncing off his body. He kicked the machine swiftly with the side of his foot. A cardboard box came down the chute and began to fill.

Norman smiled enthusiastically at Brooke. “Tell the truth,” he said. “They were great pictures, weren’t they?”

The terrace doors of the hotel suite looked out on a bright-blue Sunday-morning sky. Nothing moved on the quiet Beverly Hills street.

Brooke came down a stairway that rose from the middle of the room. She was wearing jeans, loafers and a short-sleeved white-cotton shirt. The sound of her mother’s voice followed her.

“What?” Brooke said.

Teri came down the stairs, maneuvering a piece of hand luggage in front of her. “I said, ‘Where’s the hair drier?’ ”

“In my bag,” Brooke said. She picked up the morning paper and began to flip through it. “I called downstairs. They’re sending someone up.”

Teri sorted through the remains of a box of chocolates lying on a glass coffee table. She came up with a large piece wrapped in gold foil.

“Chocolate, Mother?” Brooke said, with a narrow-eyed stare. “Before breakfast?”

“This is breakfast,” Teri said, popping the candy into her mouth.

A giant wicker basket was perched prominently on a velvet love seat near the terrace doors. It was filled with an assortment of soaps, perfumes, bath oils and herbal teas, all in paisley-print boxes, packed down in green-plastic grass.

“Wasn’t it sweet of Michael to send this?” Brooke said, admiring it.

“Adorable,” Teri said. She sat down at a writing desk and took some hotel stationery from the drawer.

“I have to write a letter to that middle-aged Romeo you ran into the other night,” she said.

“Don’t blame me; I don’t know who he is,” Brooke said. “It was late. He acted like we’d been introduced before.”

“Well, I’m going to write him and tell him that, unfortunately, you can’t sail away on his yacht to Tahiti. That you have to go back to school.”

“He’s probably married, anyway. All the cute ones are married.”

“When I sign the letter,” Teri said, scribbling the note, “I think he’ll get the picture.”

“Tell him I have a history quiz,” Brooke said. She looked at her watch. “Do you think it’s too early to call Michael?”

“He won’t mind.”

Brooke went to the telephone and punched out some numbers. The phone at the other end was answered right away.

“Hi, sleepyhead,” she said. “It’s me.”

She listened for a moment, then giggled. “Yeah, it’s early, huh?”

She paused. “I have to leave soon. I’ve got to do some stuff, then fly back.”

She moved over to the terrace, holding the phone, and looked outside. “So how was the show last night?”

As she listened, she gazed out over the rooftops of elegant houses that were as colorful and as lifeless as a David Hockney painting.

She laughed. “That sounds great. Listen, call me tonight. I’ll be home around eleven.”

She listened for a few more seconds, then said, “No, you can call me late; it’s OK. If I say it’s OK, it’s OK.”

She smiled. “OK, go back to sleep. And thanks for the basket. I love it.”

She put the phone down and turned to her mother. “He’s so sweet,” she said.

“He’s adorable,” Teri said. She stood up, sealing the letter in an envelope. She held it up. “This should cool Romeo off. Really, Brooke. How do these things happen?”

Brooke struck a demure pose.

“Haven’t you heard?” she said. “I’m America’s Dream Date.”

“They call me Pop,” the man said. He wore a green-alpaca sweater and bright-plaid trousers. He spoke with a squint. “I’m so glad you good folks could come.”

He led Brooke and Teri toward a group of low-lying buildings bordered by flat, tired lawns. A few lonely-looking palm trees stood around in the blazing sunlight like strangers at a funeral.

“We’re having a real big turnout,” Pop said. “Lots of stars.” He pointed to the hospital driveway, lined with limousines.

“Lots of soap-opera stars, is what they tell me. I don’t watch ’em, so I don’t know.” He winked at Brooke. “I know who this little lady is, though. Guess everybody does.”

Brooke looked at the man from behind her Vuarnet sunglasses and smiled.

“You folks visiting out this way?”

“We were here for the Bob Hope Christmas show,” Teri said.

“I bet he’s full of the dickens,” Pop said. He pulled open the door of one of the buildings and they stepped into a cool, dimly lit entryway.

Beyond that was a wide green corridor that looked like the Bombay airport on a bad day. People were jammed in everywhere, jostling one another and shouting back and forth. Hospital personnel were trying without success to bring order.

“Everybody’s buzzing to see Brooke,” Pop said as they moved through the crowd to the ward. “She’s the big attraction.”

There were many TV actors carrying autographed pictures of themselves, and starlets who looked like they’d just arrived from Malibu. The star of Knight Rider was there, dressed from head to toe in black Knight Rider gear, being trailed by a man pushing a hospital gurney piled high with Knight Rider toys.

All the patients in the ward were children. Many of them were attached by wires and tubes to life-support systems. Some were held in place by metal braces.

Families were clustered around each bed. The ward was strung with Christmas cards and holiday decorations, and a Christmas tree stood in one corner, its tiny colored lights blinking on and off like a signal for help.

Pop spoke to a henna-haired woman with a clip board, who then moved into the ward with purpose.

“Attention, please!” the woman said. “I’m happy to tell you that Brooke Shields is here! But everybody must settle down!”

A local anchor woman came bustling up with her camera crew. “Get shots of this!” she said, waving at Brooke. “And get shots of the toys!”

The camera crew pushed forward aggressively as Brooke walked into the ward, and they followed her with quartz lights and a boom microphone as she visited each patient.

At the end of the room, there was a Mexican boy of about 15, a plastic respirator tube taped to his nose. His head rolled to one side. There were at least a dozen relatives around his bed.

When he saw Brooke, the Mexican boy beamed with joy. Then, abruptly, he burst into tears. He shook his head from side to side.

“He’s so happy,” his mother said to Brooke. “He can’t believe he sees you.”

The tears rolled down the boy’s cheeks. His face was torn with pain as he tried to speak. The respirator at his bedside made sucking and hissing noises.

Brooke bent over, touched his forehead and whispered to him. His mother took a Kodak disc camera from the night stand and snapped their picture.

When they were in the corridor again, Teri said, “Where to now?”

“Well, let’s see,” Pop said. “We’re heading over to the cafeteria for lunch.”

“But we just got here,” Teri said. “We don’t want to eat lunch. We want to visit as many people as possible.”

The henna-haired woman stepped up. “Twelve-oh-five is the scheduled lunch meeting,” she said crisply. She regarded her clipboard. “The yellow group, the green group and the blue group all meet. Which group do you belong to?”

“No group,” Teri said. She motioned farther down the hallway. “Are there some people down this way?”

“We have activities after lunch,” the woman with the henna hair said. “We’ll have more media coverage. The Sunday show will be here.”

“We have to be on a plane in a little while,” Teri said. “Come on, Brooke.”

They turned into a wing of the building that was suddenly empty. They came to a room that had several beds, only one of them occupied. An old woman lay in it, very still, her head resting on two large pillows. On the other side of the room, a ceiling-mounted television set was showing a football game.

The old woman turned to face Brooke and Teri as if she’d been expecting them.

“How nice,” she said in a soft voice. “How very nice.”

“I came to wish you a merry Christmas,” Brooke said as she and her mother moved close.

“I’ve seen you so many times,” the old woman said. “On the television. You’re a very lovely girl.”

“Why, thank you,” Brooke said.

The old woman looked off for a moment, lost in thought. The swishing sound of a Rain Bird came through an open window. On the television, a player spiked the ball in the end zone and did a little dance.

“Are you the mother?” the woman asked, focusing again.

“Yes,” Teri said. “I’m the mother.”

“You must be very proud. Such a beautiful daughter. Such a lovely girl.”

Teri grinned at the woman. “She’s OK, I guess. For a kid.”

The woman reached her hand out and Brooke took hold of it. Her skin was so pale, it was almost translucent.

“I saw you on television. You were in a circus tent. Merv Griffin was there.”

“That was Circus of the Stars,” Brooke said.

The woman raised herself up off the pillow. She pulled Brooke down close. “You hurt yourself,” she whispered.

“Oh, no,” Brooke said. She held on to the woman’s hand very gently. “No, it wasn’t anything at all.”

The woman smiled and floated back onto the pillow. Her head made hardly any impression there at all.

“I’m so glad to hear,” she said. “I was worried about you.”

“Look what’s in here,” Brooke said, the large wicker gift basket resting on her lap.

She and Teri sat on metal chairs in a bare room with a picture window facing the airport tarmac. Sunlight poured through the window and fell in swirling shafts across the floor.

“Bubbles,” she said, holding up a plastic bottle of pink solution.

A pretty blonde girl, wearing a tuxedo shirt like a blackjack dealer, leaned into the room. “You can board in a few minutes. The TV people are almost finished setting up their equipment.”

Brooke unscrewed the cap of the bottle and took out the wand. She tried to blow a bubble, but nothing came out.

“Here, let me,” Teri said. She took the bottle and the wand and blew a fat bubble that wiggled off the end of the stick and bounced onto the floor.

“How’s that?” Teri said.

“Big deal,” Brooke said. “You have more hot air than I do.”

“It got you where you are today, kiddo.”

A young man walked briskly into the room. He was wearing chino pants, a thin-striped shirt and Top-Siders, with no socks. He looked as happy as if he’d just hit the lottery.

“This is great, letting us do the interview on the plane,” the man said. “That’s some deluxe setup in there. Separate compartments, sterling silver—like the Orient Express. I guess you have to be able to write it off, huh?”

The young man beamed and clapped his hands together. Teri sent a little school of bubbles skittering out into the air.

“I heard you just came from a hospital,” the young man said. “Was that a bummer?”

“No,” Teri said. “Not really.”

“Well, this won’t take long,” he said. “We just have a few questions.”

Brooke nodded and took the pink-plastic bottle back from her mother. The young man rocked back on his heels and smiled pleasantly.

“Just stupid questions,” he said.

Brooke held the wand up to her lips and blew a large, perfect bubble. It sailed silently across the room, toward the window, and disappeared in the sunlight like a ghost.

“I know,” she said.