For three years, Mike Tyson stayed in the same Indiana zip code, behind the same walls, while we followed the bouncing heavyweight crown from the man with the heart problem to the man who wanted to put a kitchen in his bedroom to the man who couldn’t decide if he wanted to beat up cops or become one, and finally to the old cheeseburger-eater who could make Mike Tyson rich enough to buy his own prison.

They weren’t a terrific three years for the heavyweight division, but at least they’re over. Now Tyson, the former champ, the former 922335, is finally back in a gym, punching and being punched. Ready to do for boxing what his stay in the Indiana Youth Center was supposed to do for his life: Make it better.

He was a few months away from his 26th birthday, convicted of raping an 18-year-old contestant in the Miss Black America pageant, when an Indianapolis judge gave the boxer a chance to address the court. The judge would listen and pass sentence and maybe if Tyson said all the right things, and apologized, and sounded as if he meant it, and—forget it. He spoke for 11 minutes, rambled mostly, but there was nothing close to an apology. “I don’t come here begging for mercy,” he said. “I’ve been crucified, humiliated worldwide,” he said. “My conduct was kind of crass. I have not raped anyone. I’m sure she knows that,” he said.

It was a walkover for the judge. She sentenced him to ten years and suspended the last four. With time off for good behavior, which seemed like a long shot, he would be free in three years. He handed his watch and tiepin to an attorney and hugged Camille Ewald, the woman who helped raise him after he came out of reform school at the age of 13. The next day’s headline was: WHICH TYSON WILL EMERGE FROM BEHIND BARS?

Tyson the fighter, they meant. And that’s still a question worth asking. The Indiana Youth Center is a no-boxing prison. No gloves, no ring, no ring announcer telling the crowd to drive home safely. Nobody for Tyson to box but his own shadow. He went in angry, and it cost him. Three weeks after his arrival, he exchanged words with a guard. Words, it turns out, are condoned; words that come across as threats are rule breakers. And these were threats from Mike Tyson, who once said he would punch an opponent’s nosebone back into his brain. The new kid on the cell block was banished to a lockdown unit and six weeks were added to his sentence. He had learned a lesson every bit as useful as “Tuck in your chin.”

It’s hard to tell how much money Tyson has left—Don King’s ledgers are said to be kept on the head of a match.

The people who made the 15-minute drive on U.S. 40 from the Indianapolis airport to visit Tyson—turning at the signs for company picnics and hayrides—came back with uniformly cheerful descriptions. “He was at peace with himself mentally,” says Stan Hoffman, a fight manager whose niece once dated Tyson. He says Tyson calls him Uncle Stan. “Mike’s had plenty of time to heal. He wasn’t running with women, wasn’t drinking, wasn’t doing drugs. I think he’ll be murderous. A destruction machine. A monster,” says Uncle Stan.

The prison is a medium-security facility, and Tyson lived behind a steel door, in a room that he shared with another inmate. Several times a day, Tyson used the phone in the hall, but not to make collect calls, as other prisoners did. Tyson preferred dialing Jay Bright, one of his cornermen, and Bright would then conference in the caller Tyson wanted.

“He would ask after Camille and the birds,” Bright says. The birds are 200 pigeons, homers, tumblers, fancies, highfliers, who live in a two-story coop, complete with balcony, not far from Ewald’s house in Catskill, New York. “He loves the leaders, the birds who make the others work,” Bright says. “The leaders take the other birds so high in the sky you almost can’t see them.”

It’s hard to tell how much money Tyson has left—Don King’s ledgers are said to be kept on the head of a match—but there’s certainly enough to handle the bird-talk phone bills that were charged and sent to Ewald’s Victorian home. Fourteen years ago Camille’s brother-in-law, Cus D’Amato, the brilliant and iconoclastic trainer who guided Floyd Patterson to the heavyweight title, became Tyson’s legal guardian. He was convinced that the kid from Brooklyn would be his last champion. The old man was right. When the 20-year-old Tyson won the title, becoming the youngest heavyweight champ in history, he returned to Catskill and poured champagne over Cus’ grave.

The truth is, Tyson himself is the best chance for excitement, not the parade of champions who tripped over themselves while Tyson was in storage.

Last fall, not too many minutes after Oliver McCall’s shocking second-round knockout of WBC champion Lennox Lewis, the phone rang in my home. Bright was on the line, saying, “Somebody wants to talk with you.” It was Tyson, eager to hear about his old sparring partner’s success. It didn’t bother him a bit that if Lewis had kept his share of the title, he and Tyson might have been an important match. “He never struck me as a guy who really wanted to fight,” Tyson said. “He wasn’t good for the division, wasn’t exciting. McCall will talk some trash. There’s a chance to bring some excitement into the division.”

The truth is, Tyson himself is the best chance for excitement, not the parade of champions who tripped over themselves while Tyson was in storage. “The champs and the contenders, they should thank God I’m in here,” Tyson said that night. “They wouldn’t have a career otherwise. I’m not saying that to be arrogant. It’s the truth. It’s a blessing for them that I came to this place.”

He was talking about Evander Holyfield, who later discovered he had a hole in his heart; Riddick Bowe, a gentle champ from Tyson’s old neighborhood, Brownsville, who announced he was building a mansion with a kitchen in the master bedroom; Michael Moorer, once arrested for breaking a cop’s jaw and more excited about a career in law enforcement than keeping his title; and 46-year-old George Foreman, who withstood a beating into the tenth round of his bout last year, losing every minute, before knocking out Moorer with one perfect prayer of a punch.

Where was Mr. Excitement? Sitting in a prison library, reading Cyrano de Bergerac. “The guy with the big nose,” Tyson told me. “He was a soldier, and they said to him, ‘If you’re such a great soldier, where are your medals?’ And Cyrano said to them, ‘I don’t need medals. I wear my adornments on my soul.’ I read that and I went, ‘Wow! That’s me.’”

He told Pete Hamill, another visitor, that he had read Machiavelli. “He wrote about the world we live in. The way it really is, without all the bullshit. Not just in The Prince but also in The Art of War, Discourses. He saw how important it is to find out what someone’s motivation is. What do they want? What do they want, man?”

Tyson went to class and learned about decimals. The next time he fights for millions will be the first time he’ll be able to figure out his share. He read Shakespeare and Hemingway, and about how Hemingway said he didn’t ever want to go ten rounds with Tolstoy. So Tyson took on this Tolstoy guy.

He had a prison artist tattoo a likeness of Arthur Ashe on one bicep, Mao on the other. He became a Muslim. For the first time in years, nobody was pushing him or pulling him. In years past, pushing and pulling were his life. Once, he threw punches at a heavyweight named Mitch “Blood” Green on a Harlem street at four A.M. Tyson was in the neighborhood to pick up a white leather jacket at an after-hours clothing store called Dapper Dan’s. The words on the jacket were DON’T BELIEVE THE HYPE.

He was the champ, 22 years old, knocking everybody out, running wild. Two weeks later, he drove his BMW into a tree and knocked himself out. The New York Daily News called it a suicide attempt caused by a chemical imbalance. Another three weeks passed and his wife, actress Robin Givens, told Barbara Walters on camera that their marriage was “torture, pure hell.” She called him a manic-depressive. Tyson sat at her feet, losing every round. Tyson’s response came 72 hours later; he threw furniture through their mansion windows.

Prison cuts down on those kinds of headline opportunities. At the Indiana Youth Center, he ran many miles and counted thousands of sit-ups and pushups and leg lifts. He went in weighing close to 250 pounds and lost about 30. He lifted some weights, because they were there, but that isn’t what boxers should be doing to their bodies. And there was no doubt in his mind that he would box again. (“What else am I going to do, man, be a nuclear scientist?”) More important, he said, “I’m rested. I’m getting the best rest of my life.”

Eddie Mustafa Muhammad, a former light-heavyweight champion, now a trainer, was another visitor who came away impressed. “He embraced Islam and he’s changed,” Muhammad said. “We spoke the Arabic prayer, in Arabic, and he led it. He’s been taught well. He’ll be different.”

Different?

“Humble.”

Humble Mike? Not much of a nickname. The word doesn’t compute. When Tyson stepped into a ring, his robe was a towel, worn poncho-style. He came in behind a jab and a glare that would have brought ships home safely. He was scary. For defense, he kept his head in constant motion, left, right, no telling which way. He hooked with both hands. He was powerful and his fists were fast, hard to time. He didn’t end fights with one punch, but when he hurt an opponent it wasn’t long before the referee was mercifully waving his hands and sending the crowd back to the blackjack tables.

His 28th fight, the one for the title, became his 26th knockout. His three defenses in 1988 lasted a total of seven rounds. Nobody interesting was punching out there. It seemed he would keep the title for as long as he needed a belt.

But then he started to slip. He was throwing single punches, forgetting about combinations. His head stopped ticking and became a stationary target. The glare was winking out. He was still winning, but something was missing. He had a fight in Japan against a journeyman named Buster Douglas. He didn’t want to be there. He was bored. Training was the biggest bore. Tyson must have thought the fight posters, which featured his name but not Douglas’, would be the story of the fight. Halfway through the tenth round, Tyson was on the floor, trying very hard to keep his mouthpiece from visiting friends in the third row. Buster was the winner.

Tyson’s next huge piece of news was his arrest.

Here it is, nearly four years since his last night in a ring, and the reformed, religious, rested, reading Tyson is turning grown men into fan-club members. Larry Hazzard, the New Jersey boxing commissioner, visited Tyson during his last month in jail. “He understands what he once had,” Hazzard said. “He understands he’s getting a second chance. You’re talking about a youngster who has matured. I’m glad to see boxing come out of prison.” The suggestion that Tyson might return to his former lifestyle is out of the question. “I would be totally shocked,” Hazzard said, his voice rising. “Totally. I would feel betrayed. And conned.”

He did the time, the time didn’t do him. His visitors often used that tired line. They want to believe that his turn to Islam will help stabilize his life, but it’s also true that aligning with the Muslim population is one way to protect yourself in prison. Even Mike Tyson needs protection.

“He’s matured,” said the promoter Butch Lewis, who knows mature when he sees it. Butch is famous for wearing wonderful ties over his bare chest. “He wants to be more in control of his future. He wants people around him he can trust.” Butch didn’t pay his frequent calls just to discuss the harsh Indiana winters. “It’s not going to be easy when he hits the street,” Butch said. “Everybody’s coming out of the woodwork. Nine hundred guys are claiming to have the inside track. I told him he has no idea.”

Neither do the 900 guys, whoever they are. Tyson will need several months of gym work and sparring to get his timing back, his glare working. One, maybe two fights, the experts say, and he’ll be ready to share, with Foreman, the largest pot in the history of boxing.

“The quickest way to fail is to try to please everybody,” he said. “In my heart and mind, I know I could train for a year, take two fights and then beat the champ. But that wouldn’t be smart.”

During our phone conversation, Tyson gave me a different timetable, one that would chill promoters and the pay-per-view executives. He mentioned the schedule that Foreman used when he came back to the ring in 1987 after a ten-year absence. Foreman fought more than 20 times over a three-year period before his title chance. “I’d like to do what George did,” Tyson said. “They might want to throw me in quicker. I’ll resist it.” Until it’s impossible to stop resisting.

But sitting in prison, with nobody pushing, nobody pulling, eating three regular (if dreadful) meals a day, reading about and being fascinated by the Twenties Jewish gangsters from his Brownsville neighborhood, the phone ringing only when he wanted it to, he sounded in control of his destiny. “The quickest way to fail is to try to please everybody,” he said. “In my heart and mind, I know I could train for a year, take two fights and then beat the champ. But that wouldn’t be smart. When I enter the ring again, it’ll be like my professional debut. To prepare my mind, it’s critical that I start from scratch. That 42-1, 43-1, whatever my record was, that’s over. That’s irrelevant. I start from scratch.”

A realistic scenario is that he starts with a fight in summer and another in early fall. Cus always wanted him to stay busy—Tyson fought 11 times in nine months with D’Amato in his corner—and he’ll remember that. The fights need not be against serious opponents. (As if more than one or two serious heavyweights actually exist.) There is so much curiosity about Tyson—his head, his punch, the strength of his glare—that the pay-per-view audience is expected to fork over significant dollars for insignificant bouts.

But if the deck is shuffled a new way, it’s because of the incredible payday available in a match with Foreman. The once ferocious champion of the Seventies against his Eighties counterpart, meeting halfway through the Nineties. It makes almost no sense, and there’s certainly no suspense. Tyson should walk through Foreman, punching. The fight should be a nonfight. Foreman should make sure his HMO is notified. And yet….

The champion Tyson most resembles is Smokin’ Joe Frazier, the relentless puncher whose plan of attack was to cross the ring and overwhelm. The plan worked just fine until he defended his title against the young Foreman in 1973. Frazier was knocked down a half-dozen times in two rounds. He kept getting up and walking right back into Foreman’s fists. They fought a rematch three years later and it was the same fight. When Foreman came out of retirement, Tyson was the new champ. Tyson now, Frazier then, says Foreman, he sees no difference. Until he starts talking about the money.

The record gross for a fight is the $75 million pulled in by Holyfield and Foreman in 1991. Foreman-Tyson is at least a $100 million night. Seth Abraham, president of Time Warner Sports, a man who isn’t known for hitting high notes, suggests $200 million is a possibility. The fighters would share about 75 percent. So we’re talking big and bigger, and any fight that size usually comes with problems to match.

For instance: Foreman insists he will have nothing to do with Don King, Tyson’s promoter. Foreman’s promoter of choice is Bob Arum, and here’s Arum on the subject of King: “Tyson’s back with King, unless he got smart in prison. Tyson doesn’t need a promoter. He doesn’t need anybody. All he needs is an advisor. Going with King would be a stupid thing to do. What does King bring to the table? Nothing. I bring Foreman. Tyson should fight Foreman for me and ah be gehzunt.” Which is Yiddish for I won’t take any options on Tyson’s future services if he beats Foreman. We all make a ton of money and everybody walks away happy. If I’m lying, may God strike me down, but not too hard. This better happen in a hurry, though, because how much longer can we keep feeding 200-pound guppies to George Foreman?

Foreman’s important fights have been for Time Warner. King, who calls Abraham his great enemy, jumped from that company to Showtime. Is there any chance that all this can be resolved? Well, of course, because there’s enough money involved. More than enough. And that’s what this is all about, isn’t it? Unless you listen to Mike Tyson one more time. “Who am I to think the layoff won’t affect me?” he said. “Look what it did to Muhammad Ali and Joe Louis.”

And if the layoff has taken away too much? If there ain’t no glare there? “Then I must leave boxing,” Mike Tyson said. “I’m not a fool.”

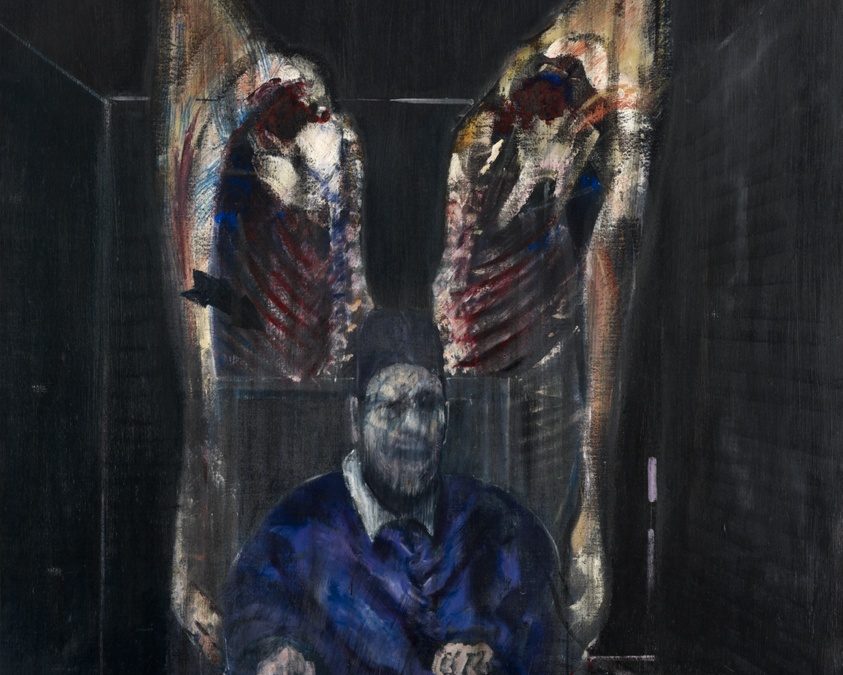

[Painting by Francis Bacon c/o The Art Institute of Chicago]