Soon after I returned to Chapel Hill , I had arranged to visit with Dean Smith, the former North Carolina head coach. I dressed up for the occasion, although these days the journalist in me had become so blasé about interviews that he tended to walk out of the house wearing whatever happened to be hanging on the nearest chair. But for Smith, I chose a dark, pinstriped suit, the sort you’d wear for an audience with the Pope, if you were the kind of guy who actually wanted to see a Pope.

As I drove across town to the Smith Center on a bright and shining winter noon, it was clear enough that the world hadn’t ended at 3:00 p.m. on Thursday, Oct. 9, 1997, but it had sure felt that way to me at the time. That was the moment when Smith stepped down after 36 years as coach of the University of North Carolina’s men’s basketball team. As a Tar Heel expatriate doing hard time in Manhattan, I’d dreaded the day for years, and when Smith announced his retirement, it felt awful, worse even than losing to Duke, though for the record I am compelled to note that had happened only once in Smith’s last nine games against the Blue Devils. Since then… well, let’s not talk about it.

Phil Ford, the former All-American point guard and then an assistant coach for the Tar Heels, captured the shock and melancholy of Smith’s departure when he said that it was “like dying.” He was right. In fact, I’d lost relatives with less disruption to my world.

Dean Smith made basketball a religion in our family, rivaled only by Presbyterianism, barbecue, and the Democratic party. For many years, our dream scenario had gone something like this: Dean beats archrival Duke and its coach, the detested Mike Krzyzewski, for the national championship in April, then runs for the Senate (for which he had long been rumored a candidate) and whips the antediluvian Jesse Helms in November! Then we all eat barbecue from Allen & Sons, on Highway 86, to celebrate. Then we go to church to thank God for sending us this wry Kansan to make our state safe for hoops and liberals. Sadly, this never happened.

By the time he retired, he’d won 879 games, more than any other coach in NCAA Division I history. Since taking over the head spot from the charismatic Frank McGuire in the 1961–1962 season, he led Carolina to two national championships, 11 Final Fours, and 13 ACC Tournament championships. Under Smith, the Tar Heels won at least 20 games for each of 27 straight seasons, 30 of his final 31. In 1976, he coached the Olympic team that restored the gold medal to the United States. In 1983, he was inducted into the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame. He had been selected by ESPN as one of the top five coaches of the twentieth century in any sport. In 1998, he received the Arthur Ashe award for courage. And his teams had graduated more than 96 percent of their lettermen. With Smith, we got to applaud not just victories, but a steadfast moral vision. It might have made us, his admirers, a little insufferable from time to time.

Over the years, we had studied him intensely. He was something of a stern mystery, a Midwestern preacher-coach thriving in the honeysuckled extravagance of the South, a play-it-close-to-the-vest Kansan whose propriety and saintly soul never quite concealed the capabilities of an assassin. He put sportswriters to sleep with his monotonic poor-mouthing (yes, we, too, respected St. Mary’s of the Blind, but we knew that on any given night they couldn’t really beat us, despite Dean’s caution). He could be something of a pious sandbagger. But you listened to him anyway, for the occasional truth he couldn’t quite hold back, like when he announced to the world that Duke’s two white stars from the late 80’s and early 90’s, Danny Ferry and Christian Laettner, had lower combined SAT scores than those of J.R. Reid and Scott Williams, two black players who were often the brunt of jokes by the Cameron Crazies; “J.R. ‘Can’t’ Reid,” they chanted during one game.

It wasn’t that we didn’t have our criticisms of El Deano (as we affectionately called him, though not to his face). He could be obstinate. In the pre-shot-clock era, he resorted too soon to the four corners, his brilliant delay game, requiring kinesthetic marvels like James Worthy and Michael Jordan to stand around, holding the ball. To the day he retired, his teams appeared to defend the three-point shot as if it were still worth only two points. His hoarding of timeouts turned us into amateur psychologists, speculating on his upbringing. What had he been denied at an early age? He substituted too much, and showed faith in reserves who seemed astonished themselves to be out on the court at crunch time.

In 1993, near the end of the nerve-wracking championship game against Michigan in the New Orleans Superdome, Smith inserted several subs, including the little-used senior guard Scott Cherry. I remember rising in my seat, wondering in unison with thousands of other disbelieving Carolina fans, “What is Dean doing?”

But as usual, Dean’s ploy worked. He got his starters some vital rest, and they played sensationally in the final seconds.

We could criticize him, of course, because we loved him. I wondered if we would ever see his like in college sports again. In fact, his type was disappearing from the world faster than the rain forests. He was that admirable paradox: the authoritarian liberal, the progressive who wasn’t a moral relativist. He treated all of his players equally. He ran a clean program. He helped integrate Chapel Hill restaurants. He supported a nuclear freeze. And he practiced Christianity quietly without the rabid proselytizing so common among the bounty-hunting Christians of today. He emphasized the virtues of tolerance, persistence, and respect.

Sometimes, his rules seemed almost niggling; if a player was late for a team meal before a game, he was held out of the game for exactly the amount of time he was late. It was one of his many lessons in responsibility to your coaches and teammates. But Smith never forgot that responsibility was a two-way street. You weren’t just responsible to him. He was responsible to you.

And unlike most present-day liberals—how strange that the label has become so disdained—El Deano won. He won a lot. Just ask that Republican Mike Krzyzewski.

It was ironic, I confess, given all of the above, that I had gone to visit Dean Smith to ask not only about Duke and North Carolina, but also about learning how to lose. But this was the sort of information that middle age demanded. I figured Smith had to know a little something about losing, or long ago he would have been poisoned from internal pressure like a diver with the bends. Admittedly, there was a paradox here; only the fact that Dean won so much underwrote his opinions about loss.

My trip to the mountain ended in a basement. For that is where I found Dean Smith—in the basement of the Dean E. Smith Center—the basement of his very own building. Ah, the contrasts were too easy to draw: Duke’s Mike Krzyzewski on the top floor of his admission-by-scanner only stone tower, the pine-needled light shining through the high windows; Dean Smith in his basement under a maze of pipes and ducts, a fluorescent world of cinder blocks and concrete floors, of dollies and spare seats and forklifts, in which he shared a windowless suite with his longtime assistant and brief successor, Bill Guthridge. On the wall of the outer office hung a Bruce Springsteen concert poster.

The cynics might call this self-effacement gaudy in its own way, conspicuous inconspicuousness. The true believers would regard the choice of location as consistent with Smith’s nearly Quaker modesty, his aversion to the growing American predilection for self-promotion. He showed what he thought about the trappings of success by moving into a cave underneath his own dome.

Smith met me with a can of Diet Coke in his hand. In contrast to my tributary apparel, he was casually dressed. His hair was whiter, but the famous nose still splayed the air like an ice cutter slicing through the Northwest Passage. He had once received mail from a North Carolina State fan addressed simply to “Coach Nose, Chapel Hill.”

Smith had a twinkling way of deflecting the expectations generated by his status of an icon. He asked me about people we knew in common, told me how much a friend of his had respected my father. He proved remarkably unassuming, but why would I have expected anything less of this particular man?

The passionate nature of the rivalries between the North Carolina schools surprised Smith when he first arrived at UNC. “Coming from the Air Force Academy,” he said, “I didn’t expect anything like this.” He attributed the ferocity partly to the strong personalities of McGuire and North Carolina State’s Everett Case, the Indiana native. McGuire was a flamboyant Irish-Catholic from New York who wore custom-made suits with handkerchiefs in their pockets, and who dined at posh restaurants without much concern for who paid. Taking the North Carolina job in 1952, he delighted the locals the way Jim Valvano would do one day at NC State. That is to say, he won, and he was a spectacle. Case was an Indiana native, a lifelong bachelor looked after by his maid. He arrived in Raleigh in 1946 and began to popularize basketball in his new state. Up to that point, the sport had been merely a bridge between football and baseball, something to occupy what was then a mostly agricultural region after the tobacco had been sold at auction and the farmers were lying low until spring. Case, too, won a lot. After his death, it was discovered that he had willed much of his estate to his former players.

“One thing people always misunderstood about Frank and Everett,” Smith said, grinning. “Frank would always run over to shake hands. Everett didn’t like to do that. He always ran to the dressing room. He said, ‘We’ll shake hands down below.’ Frank said, ‘No, I’m going to come after you and shake hands, otherwise you’re running from me.’”

Like McGuire and Case, and like his rival, Mike Krzyzewski, Smith, too, had arrived in North Carolina from elsewhere. Born in 1931, he had grown up in Emporia, Kan., then Topeka. It intrigued me how the prevailing sensibilities of Kansas and North Carolina seemed so closely matched. Each state valued the plainspoken, the modest, and the unadorned. Within that plain speech, of course, there were many ways for a man to shade his meaning, to say both more and less than was suggested by the face value of the words. Smith was a master of this. “I say what I think,” he said. “Just not everything I think.”

If Kansas were a Southern state, it would have been North Carolina, and if North Carolina were a Midwestern state, it would have been Kansas. Both states staked out the middle as if that were the most honest place to be. Topographically, Kansas lay for the most part as flat as a pool table, and North Carolina enjoyed both mountains and a coastline, but in terms of cultural geography, they were brothers. I suspected that this might be the legacy of both states’ agricultural roots. That such cultures might tend towards the laconic struck me as a reasonable response to the fact that crops were rarely impressed by the fast talkers of mercantile societies. Crops needed rain, not promises.

I tried this theory out on Smith’s longtime assistant and fellow Kansan, Bill Guthridge. It rapidly became clear that he had no idea what I was talking about.

In Kansas, Smith enjoyed an All-American boyhood, the son of stern but loving schoolteacher parents. There were inklings, though, of a more complicated world. He recounted a story about himself in high school. He played quarterback on the Topeka team with a talented black receiver named Adrian King, who he remembered had once saved a game against Salina by adroitly snaring a bad pass of Smith’s late in the fourth quarter, tying the score. “But they wouldn’t let him play basketball,” Smith said. “I went to the principal, because he was an ex–football coach who was a friend of Dad’s. I said, ‘You know, Adrian would really help our team. Why is it he has to play on his own team?’ And the principal said, ‘Dean, that was just something we decided to do because we’d have trouble with all these… you know, at the dances after the basketball games.’ And how dumb I was, I said, ‘Oh,’ and walked out.”

Despite his early run-ins with racial prejudice, Smith was still shocked when he came South the first time and saw a drinking fountain marked “Colored Only.” In tandem with a young preacher fresh in town named Robert Seymour, the leader of the new Binkley Baptist Church, Smith set about testing the willingness of local restaurants in Chapel Hill to conform to the new law guaranteeing all races equal access to businesses and public facilities.

“Chapel Hill got a reputation for liberalism from Mr. Howard Odum and the Sociology Department at the university,” said Seymour, one of Smith’s closest friends. “But Chapel Hill was as segregated as Mississippi. The only place in town where you could sit with a black was Danziger’s, a place run by a refugee from Hitler’s Germany or Austria. The former senator Frank Porter Graham said that Chapel Hill is like a lighthouse. It sends its beam into the distant darkness, but like a lighthouse, it is also dark at the base.”

Smith and Seymour decided to take a black guest to the Pines Restaurant. “We were going to test them,” Seymour said. “Dean had a vested interest in the Pines because the basketball team ate its pregame meals there. Everything went smoothly. The Pines, along with other restaurants, had been castigated by people in the community for resisting reform. We turned out to be like any other Southern town.”

But it was in that town, my town, that Smith became a moral exemplar. I remember him in his big, pimpin’ Carolina-blue Cadillac, an ocean liner of a car, nosing into a tight spot at Granville Towers during his annual summer basketball camp, at which I had managed to secure a spot through the intervention of our next-door neighbor, a donor to the athletic program. The Cadillac itself had been a gift of boosters.

Dreamer that I was, raised on sports biographies, with their morals of pluck and practice rewarded, I tried to catch Dean Smith’s eye at camp. He himself had devoured the sports novels of John Tunis, having been required by his mother to read a book a week. So he knew a little about fantasies of persistence and discovery.

We were taught, as were his players, to point a finger at the passer after receiving an assist that led to our scoring. It was a lesson in giving credit to the usually unsung, deflecting praise from the overvalued act of scoring. Paradoxically (in the usual Smith fashion), this seemed a fine way to ensure that credit came back your way. Basketball camp, therefore, became a veritable orgy of finger-pointing (the good kind). When the server at the Granville Towers chow line plopped a mound of mashed potatoes on our plates, we pointed at him. We couldn’t all be good players, necessarily, but we could all be good finger-pointers.

But I didn’t just point my finger. I ran suicides like a G.I. trying to catch a departing helicopter. I screened and cut and passed. I eschewed the dribble. I didn’t hog the ball. I knew that Smith valued teamwork above all else, that he sometimes told the story of coaching a phys-ed team at Air Force, where, as Smith put it wryly, he had a player who “shot only when he had the ball.” Smith escorted the shooter’s four teammates off the court. “Okay, play them by yourself,” he told the gunner. “Who takes the ball out of bounds, sir?” he asked Smith. “Good,” Smith told him. “Now you’ve learned that you need two, anyway.”

I did have my suspicions that, despite what coaches say about the value of sharing the ball, there was danger at basketball camp in being consigned to the unseen role of hustler, like being a helpful spinster aunt in a Jane Austen novel. You ended up blending so well into the woodwork that you weren’t actually seen. Better, perhaps, to shoot a lot, though if you were going to do that, better to hit the shots.

Sad to say, I don’t think Dean Smith caught a glimpse of my heroic screen-setting. I did attract the notice of Bill Guthridge, but that was for whistling “Stairway to Heaven” while waiting to be subbed into a game. “Way to whistle,” he said. He winked at me, patted me on the shoulder, and kept on walking.

There were times when Dean Smith’s story seemed more familiar to me than my own. Though he would never admit it, it was something of a saint’s tale—a saint who snuck cigarettes before games in the entryways of gymnasiums, who drank liquor and got divorced and kept a messy desk and loved winning and hated losing, and who kept score with a long memory for jibes and doubters and cheaters. “Dean never forgets anything,” the journalist Bill Brill told me. “And he won’t let you forget it, either.” Brill recalled that when North Carolina won Smith his first national championship in 1982, Dean’s first order of business in the victorious press conference was to respond to Frank Barrows, a writer for The Charlotte Observer, who had suggested several years before that Smith’s teams made such a fetish of consistency that they would never be able to achieve the peak performances necessary to win it all.

And yet, all of these qualities just made his goodness seem more plausible to us everyday sinners. There was something old-fashioned about learning morality through the example of a human being—not from books or sermons or stone tablets, but from an actual life in front of you. Someone who was grinding through the same existence we all were, and yet demonstrated the allure of goodness, who made a case for an ethical behavior rooted in compassion and fellow-feeling—not in the fear of hellfire and damnation, nor in the dictates of the Bible as the ultimate rule book, as was so common in my native South even to this day.

I asked Seymour to what he attributed Smith’s decency. He thought for a moment, then said, “I attribute this to a sound upbringing in a good family. He had a family that gave him the good sense to care about others.” “Value each human being,” Smith’s father used to tell him.

Smith extended the realm of family to his players, upon whom he exerted an abiding moral influence as a compassionate but tough-minded paterfamilias. Not even Michael Jordan, whose freedom to do what he wished must have felt near-absolute during his glory days with the Chicago Bulls, who as a sporting demigod enjoyed immunity from simple necessities like waiting in line—not even Jordan could escape Smith’s moral suasion. It was as if his former coach had become a voice in his head, a conscience that spoke with that nasally Kansas twang.

As recounted by David Halberstam in his biography, Playing for Keeps, Jordan, then a few years into his career as a Bull, arrived late for a preseason exhibition game at Carmichael Auditorium on the UNC campus, where parking was hard to come by on the best of days. Jordan drove into the parking lot next to the gym, only to discover every space filled, except for a single handicapped spot. “Why don’t you take it?” his friend Fred Whitfield asked.

“Oh, no, I couldn’t do that,” Jordan answered. “If Coach Smith ever knew I had parked in a handicapped zone, he’d make me feel terrible. I wouldn’t be able to face him.”

The question that Smith seemed to answer with his life was how you competed in this dog-eat-dog society, how you competed and even won without turning into a monster. Clearly, Smith hardly minded winning. In fact, he hated to lose.

He revealed that his composure concealed powerful extremes of emotion. “Sometimes I get so upset at myself,” he said, speaking in the present tense. “I don’t let it show, but I’m really mad.” He cited a game that happened nearly 15 years ago against Georgia Tech, in which the Yellow Jackets’ Dennis Scott beat UNC at the last second with a three-pointer, falling out of bounds. Smith blamed himself for not having coached a better end of the game.

“Win or lose,” he said, “I go to sleep. Then I wake up the next morning and it hurts worse.” He seemed relieved not to have to go through that anymore. “I don’t read the paper after a loss,” he added.

“So how did you learn to lose?” I asked. “It seems coaches would go insane if they didn’t.”

The answer, Smith suggested, lay in a notion called “the power of helplessness,” a concept introduced by the writer Catherine Marshall, whom he’d come across in his 30’s when reading religious thinkers like Søren Kierkegaard, Karl Barth, Dietrich Bonhoeffer, and Martin Buber, among the many suggested to him by Bob Seymour. “Crisis brings us face to face with our inadequacy,” Marshall had written in a book called Beyond Our Selves. “And our inadequacy in turn leads us to the inexhaustible sufficiency of God. This is the power of helplessness, a principle written into the fabric of life.”

Smith discovered Marshall’s work the same week in 1965 that he was hanged in effigy—twice—in front of Woollen Gym by Carolina students unhappy with the direction of the program under his leadership. A few days after the latter hanging, the Tar Heels upset sixth-ranked Duke at Cameron, 65 to 62. Invited to speak to a celebrating crowd of students outside of Woollen upon the team’s return, Smith declined. “I can’t,” he said. “There’s something tight around my neck that keeps me from speaking.”

He learned how to apply Marshall’s lessons directly to coaching. Giving up in that context meant teaching his players to surrender to the present moment in practice and in games, not to fret about something that was beyond their control in either the future or the past. They were to let go of what they could not control. He helped them—and himself—side-step the self-immolating demands of victory at all costs. “When we talked to our team over the years,” he told me, “our emphasis was always play hard, play smart, and play together. We didn’t mention winning. The emphasis was on process versus end result.” Many would find it ironic that a coach famous for controlling everything he could ultimately believed in letting go. But the most important lesson of all, one that had generated decades of loyalty from his former players, was Smith’s equal treatment of every player, from benchwarmers to stars. He wanted to show them that their value as human beings was separate from their performance on the court.

“The emphasis on process—was that just a sneaky way to get the result you wanted, i.e., winning?” I asked.

“You could say that,” Smith said with a Mona Lisa smile. I didn’t know whether the smile suggested a realization of the contradiction between not thinking about winning so that you could win, or whether it was simply an acknowledgment that coaches were in business to win and that if they didn’t, they’d shortly be in the broadcasting business. But that you might as well try to win in a dignified and decent manner. And lose that way, too.

In this part of the world, coaches were philosopher-kings, their evident wisdom on such matters as full-court pressure and team dynamics eventually translated into realms far afield; both Smith and Mike Krzyzewski had written books applying their coaching secrets to business success. Not long ago, Smith had finished his manual, called The Carolina Way: Leadership Lessons from a Life in Coaching. Krzyzewski had published a book entitled Leading with the Heart: Coach K’s Successful Strategies for Basketball, Business, and Life. Journalists sought their opinions on matters like the war with Iraq. Politicians asked for their help in fund-raising.

And yet for all of that, one of the things I admired about Dean Smith was that the American vogue for self-promotion appeared lost on him. He didn’t court publicity in a country where hype, good or bad, had become a value in its own right. I doubted he had his own blog, for instance. Or that he would be making a commercial for American Express in which he said, “I don’t look at myself as a basketball coach. I look at myself as a leader who happens to coach basketball.”

He inveighed against the way TV, for instance, zeroed in on the sideline antics of coaches. He had once asked a CBS executive to stop showing coaches during their college basketball broadcasts. “But it’s good for the game!” the astounded executive responded.

“Too much is made of this coach-versus-coach business,” Smith told me. “It’s a player’s game.”

As for the Duke–Carolina rivalry, his initial position appeared to be: What rivalry? This was vintage Dean Smith. In time, he qualified his view.

He admitted that Duke under Vic Bubas had proved a tough opponent in the 60’s. But in the latter part of that decade, Smith’s program caught fire, in part when he out-recruited the Blue Devils for the high school All-American Larry Miller, a 6-foot-4 bruiser from Catasauqua, Penn. “He was the big breakthrough,” Smith said. “By the time he was ready to sign, Duke had a class of six committed. And Larry said, ‘Gosh, I won’t get any playing time on the freshman team if I go there.’” From 1967 to 1969, the Tar Heels won three straight ACC Tournaments at a time when only the tournament champion advanced to NCAA play. And for those same three years, UNC went to the Final Four, losing in the championship game in 1968 to UCLA and Lew Alcindor. Duke began a slow fade from sight.

The following decade, Smith said, “There wasn’t really any Duke–Carolina rivalry.” He thought for a moment. “The team that’s beating you is the team that becomes your big rival.” In the 70’s, that meant North Carolina State, with David Thompson, had been Carolina’s most detested foe. Then Maryland for a time. Then, in the early 80’s, Virginia, with Ralph Sampson at center and Terry Holland as coach. (Holland had named his dog Dean because—as he put it—the dog whined a lot.) “After Sampson left… I was trying to remember… Duke… they didn’t beat us much.”

And then Smith said, as if trying to recollect something lost in the recesses of either time or his mind: “Duke… I suppose they did come on about ‘85 or ‘86.”

How Smithian, that “I suppose”! In a sense, Smith’s reluctance to put Duke into a special category was the cagiest, most rivalrous move of all. By not considering your archrival your archrival, you were injuring him at his most vulnerable point: You refused to give him the prominence he gave you. You were saying he simply wasn’t that big a deal! You were saying there was a long list of competitors of which he was one and that perhaps at certain times in the historical record, Duke may have amounted to a pretty good team. But that in the long march, Duke was as often as not standing at the curb, watching the parade go by. Masterful! Ingenious! Devious! And brilliant!

In 1985, Duke successfully out-recruited North Carolina for Danny Ferry. “When we lost Danny Ferry,” he told me, “that was the start of their program.” This was the same Danny Ferry whose SAT performance was to become a matter of public comment by Smith.

“John Feinstein was furious with me about that,” Smith said of the Duke-educated journalist, author of A Season on the Brink, a rather terrifying glimpse into the mind of Bobby Knight. “He said it was the worst thing that I commented how Reid’s and Williams’s SATs combined surpassed Ferry’s and Laettner’s. I said, ‘How do you know that all of them didn’t score 1400 or 1500?’ Feinstein was so much of a Duke guy.”

The controversy occurred the same week as the 1989 ACC Tournament finals, which, in karmically just fashion, ended up being between Duke and North Carolina. The game was a bitterly contested slugfest, bodies bouncing about the lane, every shot challenged. At one point, Krzyzewski stared down the sideline at Smith and yelled, “Fuck you,” a remark that was instantly entered in the unexpurgated ledgers of the rivalry. The outcome wasn’t decided until Ferry barely missed a long heave at the end of the game. The Tar Heels prevailed, 77 to 74, a win that doubtless gave Smith great satisfaction.

By the time he resigned in 1997, Smith had gone on quite a run against the Blue Devils. “I’d have to check,” he said, “but I think Duke beat us once in about ten times before I retired.”

“That is exactly right,” I said. I knew. Those sorts of things mattered to me, too.

I had come to visit a saint of the everyday to learn about how to be good and how to lose with grace, and had discovered a coach who was still competing, sitting down there in his very own basement giving as good as he ever got—or better. Let the games continue.

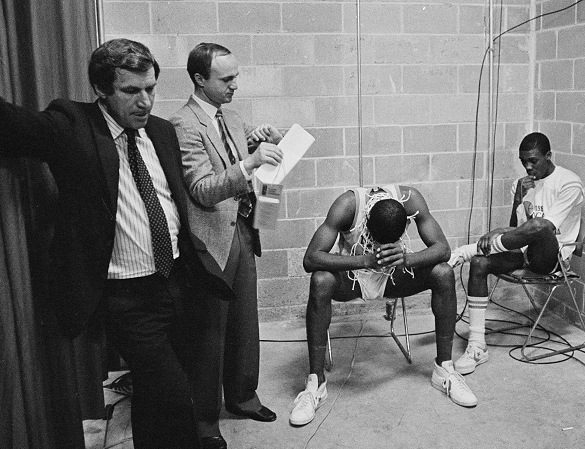

[Photo Credit: Hugh Morton]