Preface

I have a dream in which Joseph Cornell and I pass each other on the street. This is not beyond the realm of possibility. I walked the same New York neighborhoods that he did between 1958 and 1970. I was either working at lowly office jobs, or I was out of work spending my days in the Public Library on Forty-second Street which Cornell frequented himself. I don’t remember when it was that I first saw his shadow boxes. When I was young, I was interested in surrealism, so it’s likely that I came across his name and the reproduction of his art that way. Cornell made me feel that I should do something like that myself as a poet, but for a long time I continued to admire him without knowing much about him. Only after his death did he become an obsession with me. Of course, much had already been written about him, and most of it was excellent. Cornell’s originality and modesty disarm the critics and make them sympathetic and unusually perceptive. When it comes to his art, our eyes and imagination are the best guides. In writing the pieces for this book, I hoped to emulate his way of working and come to understand him that way. It is worth pointing out that Cornell worked in the absence of any aesthetic theory and previous notion of beauty. He shuffled a few inconsequential found objects inside his boxes until together they composed an image that pleased him with no clue as to what that image will turn out to be in the end. I had hoped to do the same.

MISS DELPHINE

On the streets Cornell walked forty years ago, there were still medical leech dealers; importers of armadillo meat and ostrich eggs. There were people like Miss Delphine Binger, who collected goose, turkey, and chicken wishbones so she could boil them and polish them and then decorate them with charms and ribbons. She sent them to presidents, movie stars, famous politicians in the same way Cornell sent gifts of scraps of paper and odd objects to ballerinas he loved.

THE MAN ON THE DUMP

He looked the way I imagine Melville’s Bartleby to have looked the day he gave up his work to stare at the blank wall outside the office window.

There are always such men in cities. Solitary wanderers in long-outmoded overcoats, they sit in modest restaurants and side-street cafeterias eating a soft piece of cake. They are deadly pale, have tired eyes, and their lapels are covered with crumbs. Once they were something else, now they work as office messengers. With a large yellow envelope under one arm, they climb the stairs to the tenth floor when the elevator is out of order. They keep their hands in their pockets even in summertime. Any one of them could be Cornell.

He was a descendant of an old New York Dutch family that had grown impoverished after his father’s early death. He lived with his mother and invalid brother in a small frame house on Utopia Parkway in Queens and roamed the streets of Manhattan in seeming idleness. A devout Christian Scientist, he was a recluse and an eccentric who admired the writings of French Romantic and Symbolist poets. His great hero was Gérard de Nerval, famous for promenading the streets of Paris with a live lobster on a leash.

THE ROMANTIC MOVEMENT

Poe has a story called “The Man of the Crowd” in which a recently discharged hospital patient sits in a coffee shop in London, enjoying his freedom, and watching the evening crowd, when he notices a decrepit old man of unusual appearance and behavior whom he decides to follow. The man at first appears to be hurrying with a purpose. He crosses and recrosses the city until the aimlessness of his walking eventually becomes obvious to his pursuer. He walks all night through the now-deserted streets, and is still walking as the day breaks. His pursuer follows him all of the next day and abandons him only as the shades of the second evening come on. Before he does, he confronts the stranger, looks him steadfastly in the eye, but the stranger does not acknowledge him and resumes his walk.

Poe’s is one of the great odes to the mystery of the city. Who among us was not once that pursuer or that stranger? Cornell followed shop girls, waitresses, young students “who had a look of innocence.” I myself remember a tall man of uncommon handsomeness who walked on Madison Avenue with eyes tightly closed as if he were listening to music. He bumped into people, but since he was well dressed, they didn’t seem to mind.

“How wild a history,” says Poe’s narrator, “is written within that bosom.” On a busy street one quickly becomes a voyeur. An air of danger, eroticism, and crushing solitude play hide-and-seek in the crowd. The indeterminate, the unforeseeable, the ethereal, and the fleeting rule there. The city is the place where the most unlikely opposites come together, the place where our separate intuitions momentarily link up. The myth of Theseus, the Minotaur, Ariadne, and her thread continue here. The city is a labyrinth of analogies, the Symbolist forest of correspondences.

Like a comic-book Spider-Man, the solitary voyeur rides the web of occult forces.

WHERE CHANCE MEETS NECESSITY

Somewhere in the city of New York there are four or five still-unknown objects that belong together. Once together they’ll make a work of art. That’s Cornell’s premise, his metaphysics, and his religion, which I wish to understand.

He sets out from his home on Utopia Parkway without knowing what he is looking for or what he will find. Today it could be something as ordinary and interesting as an old thimble. Years may pass before it has company. In the meantime, Cornell walks and looks. The city has an infinite number of interesting objects in an infinite number of unlikely places.

TERRA INCOGNITA

America still waits to be discovered. Its tramps and poets resemble early navigators setting out on journeys of exploration. Even in its cities there are still places left blank by the map makers.

This afternoon it’s a movie house, which, for some reason, is showing two black-and-white horror films. In them the night is always falling. Someone is all alone someplace they shouldn’t be. If there’s a house, it must be the only one for miles around. If there’s a road, it must be deserted. The trees are bare, or if they have leaves, they rustle darkly. The sky still has a little gray light. It is the kind of light in which even one’s own hands appear unfamiliar, a stranger’s hands.

On the street again, the man in a white suit turning the corner could be the ghost of the dead poet Frank O’Hara.

I WENT TO THE GYPSY

What Cornell sought in his walks in the city, the fortune-tellers already practiced in their parlors. Faces bent over cards, coffee dregs, crystals; divination by contemplation of surfaces which stimulate inner visions and poetic faculties.

De Chirico says: “One can deduce and conclude that every object has two aspects: one current one, which we see nearly always and which is seen by men in general; and the other, which is spectral and metaphysical and seen only by rare individuals in moments of clairvoyance…”

He’s right. Here comes the bruja, dressed in black, her lips and fingernails painted blood-red. She saw into the murderer’s lovesick heart, and now it’s your turn, mister.

OLD POSTCARD OF 42ND STREET AT NIGHT

I’m looking for the mechanical chess player with a red turban. I hear Pythagoras is there queuing up, and Monsieur Pascal, who hears the silence inside God’s ear.

Eternity and time are the coins it requires, everybody’s portion of it, for a quick glimpse of that everything which is nothing.

Night of the homeless, the sleepless, night of those winding the watches of their souls, the stopped watches, before the machine with mirrors.

Here’s a raised hand covered with dime-store jewels, a hand like “a five-headed Cerberus,” and two eyes opened wide in astonishment.

BIRDS OF A FEA THER

Cornell loved Houdini, who was famous for escaping from ingeniously constructed boxes. The boxes had secret trapdoors and exits and could be dropped in the sea with Houdini variously bound and chained in them. Some said Houdini made his escapes by dematerializing himself and then resuming his human form.

That art is called illusionist. Illusionists make it seem. It appears that the lady in the coffin is being sawn in half, except she isn’t. There are two points to make about this: (1) philosophically, illusionism is a theory that the material world is an illusion; (2) illusionism is a technique of using images to deceive. It raises the question of whether perception can give us true and direct knowledge of the world. Psychologists, for instance, have constructed a “distorted room” in which a grown man appears to be the size of an infant. Other examples are funhouse mirrors and the conjurer’s sleight of hand. Cinema, of course, is the most successful illusionist’s trick yet.

The eyes cannot be philosophically trusted, but in the meantime they can be entertained. Nature, too, makes fakes—fake masterpieces of art, we should say. All these splendid sunsets are mere illusions and cannot be true of real objects and properties. The evening sky and the big city in the distance are constantly changing their theatrical scenery. We don’t really believe any of this, but it sure looks that way sometimes.

THE LITTLE BOX

The little box gets her first teeth

And her little length

Little width little emptiness

And all the rest she has It

The little box continues growing

The cupboard that she was inside

Is now inside her

And she grows bigger bigger bigger

Now the room is inside her

And the house and the city and the earth

And the world she was in before

The little box remembers her childhood

And by a great great longing

She becomes a little box again

Now in the little box

You have the whole world in miniature

You can easily put it in a pocket

Easily steal it easily lose it

Take care of the little box.

—Vasko Popa

CHESSBOARD OF THE SOUL

Around the boxes I can still hear Cornell mumble to himself. In the basement of the quiet house on Utopia Parkway he’s passing the hours by changing the positions of a few items, setting them in new positions relative to one another in a box. At times the move is no more than a tenth of an inch. At other times, he picks the object, as one would a chess figure, and remains long motionless, lost in complicated deliberation.

Many of the boxes make me think of those chess problems in which no more than six to seven figures are left on the board. The caption says: “White mates in two moves,” but the solution escapes the closest scrutiny. As anyone who attempts to solve these problems knows, the first move is the key, and it’s bound to be an unlikely appearing move.

I have often cut a chess problem from a newspaper and taped it to the wall by my bed so that I may think about it first thing in the morning and before turning off the lights at night. I have especially been attracted to problems with minimum numbers of figures, the ones that resemble the ending of some long, complicated, and evenly fought game. It’s the subtlety of two minds scheming that one aims to recover.

At times, it may take months to reach the solution, and in a few instances I was never able to solve the problem. The board and its figures remained as mysterious as ever. Unless there was an error in instructions or position, or a misprint, there was no way in hell the white could mate in two moves. And yet…

At some point my need for a solution was replaced by the poetry of my continuous failure. The white queen remained where it was on the black square, and so did the other figures in the original places, eternally, whenever I closed my eyes.

THE MAGIC STUDY OF HAPPINESS

In the smallest theater in the world the bread crumbs speak. It’s a mystery play on the subject of a lost paradise. Once there was a kitchen with a table on which a few crumbs were left. Through the window you could see your young mother by the fence talking to a neighbor. She was cold and kept hugging her thin dress tighter and tighter. The clouds in the sky sailed on as she threw her head back to laugh.

Where the words can’t go any further—there’s the hard table. The crumbs are watching you as you in turn watch them. The unknown in you and the unknown in them attract each other. The two unknowns are like illicit lovers when they’re exceedingly and unaccountably happy.

WHAT MOZART SAW ON MULBERRY STREET

If you love watching movies from the middle on, Cornell is your director. It’s those first moments of some already-started, unknown movie with its totally mysterious images and snatches of dialogue before the setting and even the vaguest hint of a plot became apparent that he captures.

Cornell spliced images and sections from preexisting Hollywood films he found in junk stores. He made cinema collages guided only by the poetry of images. Everything in them has to do with ellipses. Actors speak but we don’t know to whom. Scenes are interrupted. What one remembers are images.

He also made a movie from the point of view of a bust of Mozart in a store window. Here, too, chance is employed. People pass on the street and some of them stop to look in the window. Marcel Duchamp and John Cage use chance operation to get rid of the subjectivity of the artist. For Cornell it’s the opposite. To submit to chance is to reveal the self and its obsessions. In that sense Cornell is not a dadaist or a surrealist. He believes in charms and good luck.

THE GAZE WE KNEW AS A CHILD

“People who look for symbolic meaning fail to grasp the inherent poetry and mystery of the images,” writes René Magritte, and I could not agree more. Nevertheless, this requires some clarification. There are really three kinds of images. First, there are those seen with eyes open in the manner of realists in both art and literature. Then there are images we see with eyes closed. Romantic poets, surrealists, expressionists, and everyday dreamers know them. The images Cornell has in his boxes are, however, of the third kind. They partake of both dream and reality, and of something else that doesn’t have a name. They tempt the viewer in two opposite directions. One is to look and admire the elegance and other visual properties of the composition, and the other is to make up stories about what one sees. In Cornell’s art, the eye and the tongue are at cross purposes. Neither one by itself is sufficient. It’s that mingling of the two that makes up the third image.

UTOPIA CUISINE

It’s raining on Utopia Parkway. The invalid brother is playing with his toy trains. Cornell is reading the sermons of John Donne, and the box of the Hôtel Beau-Séjour is baking in the oven like one of his mother’s pies.

In order to make them appear aged, Cornell would give his boxes eighteen to twenty coats of paint, varnish them, polish them, and leave them in the sun and rain. He also baked them to make them crack and look old.

Forgers of antiquities, lovers of times past, employ the same method.

STREET-CORNER THEOLOGY

It ought to be clear that Cornell is a religious artist. Vision is his subject. He makes holy icons. He proves that one needs to believe in angels and demons even in a modern world in order to make sense of it.

The disorder of the city is sacred. All things are interrelated. As above, so below. We are fragments of an unutterable whole. Meaning is always in search of itself. Unsuspected revelations await us around the next corner.

The blind preacher and his old dog are crossing the street against the oncoming traffic of honking cabs and trucks. He carries his guitar in a beat-up case taped with white tape so it looks like it’s bandaged.

Making art in America is about saving one’s soul.

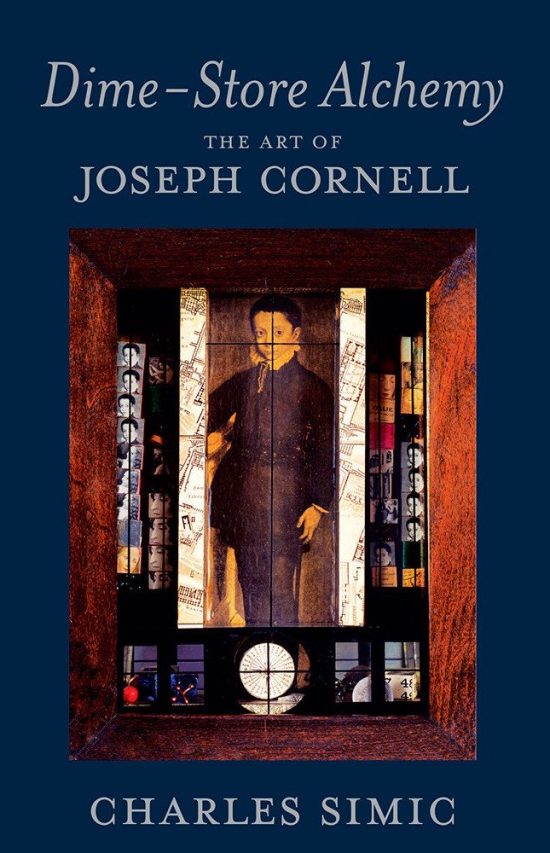

[Photo Credit: Bags, AB]

From Dime-Store Alchemy: The Art of Joseph Cornell, reprinted with the author’s permission.