The way Wayne Newton explained it to me, it all started with a post-midnight punch-out in a private suite at the Frontier hotel.

Wayne is knocking them dead in the Frontier’s showroom when these two wise guys swagger onto the casino floor and start knocking Wayne. Loudly. They’re demanding to see the singer, and they’re not just talking tickets to the second show. No way: they’re not going to be satisfied unless they get a face-to-face sit-down with the Midnight Idol, a “business meeting.” About some partnership deal they claim Wayne backed out of. Well, people begin to get alarmed. The casino “host” tries to quiet the troublemakers down. No dice. They’re not leaving until they settle their problems with Wayne Newton personally.

The casino host calls up to Wayne’s dressing room between shows, tells him these two bad-news guys claim to know him from some deal. Wayne recognizes one of the names. It seems he had been involved with this guy to the extent of cosigning a $100,000 note to fund an entertainment supplement the guy was publishing. But the money and the supplement have sunk out of sight, and Wayne doesn’t want to sink any more into it. He doesn’t want to see the guy or his loud-talking friend.

So what Wayne does first is send the Bear down to talk to the guys. “The Bear” is what they call Mike Forch, Wayne’s longtime personal aide, a very large person whose intimidating size and ursine demeanor make him a formidable bodyguard. The Bear goes up to them and tries to explain it in a gentlemanly way: no more business deals, no personal audience with Wayne.

But the wise guys aren’t gonna take no for an answer even from the Bear. They’re gonna see Wayne, they say, or …

“So,” Wayne tells me, “I tell Bear to get a suite and we go upstairs and I go walking into the room and this one guy I don’t know comes up to me and he says, ‘Lissen Newton,’ with his finger in my chest. So I backhanded him and knocked him about thirty feet. Then I grabbed the other one and I said, ‘What is this?’ and he’s gettin’ off the floor and says, ‘I’m your partner.’

“‘Partner in what?’ I say.

“‘In the paper,’ he says.

“I said, ‘I understand it’s broke. Is that a fact?’ and this guy wouldn’t answer me, so I slapped him. Then they went running out of the room and the next thing I know we were getting all these death threats . . .”

Well, in the fullness of time, the death threats led Wayne to make the fateful call to a fearsome fellow known as Guido the Bull, which somehow led to a sit-down in a Bridgeport, Connecticut, delicatessen with some members of the Gambino crime family, which brought the death threats to a dead stop but started up a new series of anonymous calls attempting to extort from Wayne a hidden interest in his Aladdin Hotel Casino, which led to a secret grand jury investigation and the specter of “hidden interests, ” to the rumor of Wayne’s “singing” and, in turn, another series of death threats, which sent him fleeing to Mexico for safety.

It’s a tangled tale, and the bits and pieces that have come out in the papers have left a lot of people wondering just how the original choirboy, Wayne Newton, got involved with such bad company. Was there some secret Sinatra-like web of “friendships” with the boys in the Bridgeport deli?

If you know Las Vegas, you that Wayne Newton is not a Wayne Newton joke anymore.

But let’s backtrack a little here, back to that Frontier punch-out. Let’s look at what we might call a perceptual error on the part of the two original bad-mouthing loud guys, a miscalculation that might have dawned on them as they sailed across the suite. It’s something anyone who knows Las Vegas knows by now; it’s something even Johnny Carson knew by then: Wayne Newton is not a Wayne Newton joke anymore.

If you know Las Vegas, you know that already. If you know Las Vegas, you know Wayne Newton is more than the Midnight Idol, more than Mr. Excitement in Vegas; he’s the center of a veritable cult in the town. If you don’t know Vegas, if you haven’t been accosted by travelers “just back from Vegas” raving about the supreme peak experience of being present at a Wayne Newton performance, if you haven’t heard the worshipful reverence with which hardboiled Las Vegas locals, cynical casino dealers, and sophisticated chorus girls all speak of “Mr. Newton,” then you’re probably stuck with a woefully outdated image of Wayne. You probably still have a vague two-decades-old memory of a chubby, pubescent kid with the prepubescent baby-fat soprano voice belting out schmaltzy throwback “novelty” hits like “Danke Schoen” and “Red Roses for a Blue Lady.”

If you don’t know Vegas, you might be tempted to class Wayne with Tiny Tim as a brief freakish aberration in the evolution of pop music, a phenomenon preserved as a cultural artifact only as the occasional butt of jokes in Johnny Carson monologues.

But Johnny Carson doesn’t tell Wayne Newton jokes anymore. Not since a hulking six-foot-three black-belt karate expert named Wayne Newton walked into Carson’s office, flexed the muscles he’d pumped up with Steve “Hercules” Reeves, and all but threatened to thrash the comedian if he didn’t cut out the ridicule of Newton’s formerly fat and effeminate image (“He was makin’ fag jokes about me” is the way Wayne explained it to me). Not since Wayne got the last laugh on Carson in the fierce struggle for possession of the huge Aladdin Hotel Casino, succeeding where Carson and his partners had failed in their bid to take over the huge $100 million Strip property and teaching the comedian a lesson in Las Vegas power plays.

If you know Vegas, you know Wayne Newton has become a big-shot, macho power broker, a tough guy in the toughest town left in the West. He has built an entertainment empire out of what was once a lounge act, transformed himself into a Tom Jones-type sex symbol, become the highest-grossing entertainer in Las Vegas history (surpassing Sinatra and Elvis)—the only entertainer ever to become an owner of a casino.

If you know Vegas, you know that somehow this formerly fat kid with only two top-ten hits in the past two decades has somehow captured and concentrated, become an emblem of, the essence of Vegasness. Or, as that sage of show biz, Merv Griffin, so succinctly summed it up: “Las Vegas without Wayne Newton is like Disneyland without Mickey Mouse.”

All of which raises the large and disturbing question: Do we really know Vegas?

Sure, we know the dark, apocalyptic images that appear repeatedly in Vegas literature. We all know the hellish “fear and loathing” in Hunter Thompson’s “Savage Journey to the Heart of the American Dream.” The air-conditioned purgatory for unpunished sinners in Norman Mailer’s An American Dream. The sinister gangster glamour of The Godfather’s Vegas. The scarred and pitted psyches of the lost-soul small-timers in John Gregory Dunne’s Vegas: A Memoir of a Dark Season.

Darkness. Evil. Apocalypse. Most Vegas literature projects our sinful national self-consciousness onto the city, forcing it to serve as the dark mirror of our most nightmarish image of ourselves.

But Wayne Newton? He doesn’t exactly fit into this vision of Vegas, does he?

“The young son of two half-American Indians had a dream of success,” Wayne’s press kit biography informs us, “and because of his dream, his hard work, his talent and involvement Wayne Newton has embodied the American dream.” The nightmare metropolis that Hunter Thompson fled, feeling like a “monstrous reincarnation of Horatio Alger,” is home sweet home to the innocent Horatio Alger dream of the man they call Mr. Las Vegas.

And so I set out for Las Vegas to spend a couple of weeks with Wayne and his entourage, convinced that the literature has failed to fully fathom the fabled city, and certain that if we can’t understand the Wayne Newton phenomenon, we can’t really say we know Las Vegas.

Hidden Interests

Evening at the Aladdin Hotel, Wayne’s Bizarro-Byzantine Arabian Nights gambling palace. A huge tower on the south end of the Strip financed by Teamster loans, the Aladdin was put up for grabs when the last set of owners got themselves convicted in federal court of violating the laws against allowing “hidden interests” access to casino cash.

Up on the football-field-sized casino floor, the evening action is beginning to build, but the real spectacle is the long line of faithful pilgrims snaking its way around the tables and the slots, devoutly staring ahead at the as-yet-unopened doors of the Bagdad Showroom. Some of them have been positioning themselves since before noon for a chance at a choice seat at the first of Wayne’s two nightly appearances.

Down in the dressing room complex, nestled in the casbah of corridors beneath the Bagdad Showroom stage, the inner circle of Wayne’s retainers and favorites have begun to gather, awaiting the arrival of the Chief, as they call him—in part out of deference to his half-Indian heritage, in part just out of deference.

It’s a cozy, self-contained complex, consisting of Wayne’s inner sanctum, where Peaches, his wardrobe mistress, is readying Wayne’s wine-dark second-show tux, and an outer party room, complete with couches and plush carpeting, wet bar, videocassette and stereo setups, and a crew of aides, bodyguards, and acolytes.

Sitting at the wet bar, I’m listening to a strange story told by two of the Chief’s key attendants: Lola Falana, the slinky black songstress who has attributed her metamorphosis from TV-commercial curiosity to Vegas headliner to Wayne’s showbiz wizardry; and Mona Matoba, Wayne’s feisty longtime executive secretary.

Lola and Mona are mulling over the puzzling denouement of the latest example of Wayne’s healing powers.

Yes, healing powers. Several members of the Wayne Newton cult have told me stories of miraculous recoveries from dread diseases, directly attributable to the Midnight Idol’s healing ministrations, as if he were a kind of show-biz shaman.

This latest story Lola and Mona are analyzing starts out like another of those triumphant tales of show-biz sentiment but takes an unexpected twist.

There was this young girl in Kentucky who worshiped Wayne above all others who walked the face of the earth. But she was dying of MS and it looked like she’d never get to see her one dream come true: to watch Wayne onstage in Vegas.

Somehow Wayne heard about the situation. He arranged for her and her family to be flown at his expense to Vegas to see the show and then on to Disneyland.

Wayne bursts through the dressing room door, trailed by Peaches and a cloud of Paco Rabanne.

The news seemed to have a galvanizing effect on the little girl’s health: she realized she had something to live for. By the time she touched down in Vegas, by the time Wayne brought her up onstage and kissed her at the height of his show, sang his heart out for her, her improvement, everyone said, had been nothing short of miraculous.

But then, two days later, she died suddenly, before reaching Disneyland. After Wayne, it seemed, the Magic Kingdom had little lure; after Wayne she had nothing left to live for.

Shaking his head over this sad turn of events is the Bear, Wayne’s chief aide. Besides dealing with the wise guys in the Frontier, he stands at the locked dressing room door after the show deciding which of the people who line up backstage are to be admitted to the nightly party that continues long after Wayne goes home to his wife and Casa De Shenandoah, his mansion in the desert.

Then there is Michael, a slim, serious-looking fellow who stands behind the bar and, while tending to business there, seems to sweep the room with wary eyes. I don’t know if Michael’s primary job is security. I do know that a week later, just before we board the Learjet to take us from Vegas to San Antonio, where Wayne will meet with President Reagan, I watched Michael remove a sleek handgun from a shoulder holster and flip it into the trunk of one of Wayne’s limos, leaving the gun behind in deference to the Secret Service’s preference for a monopoly of firepower around the President.

The thunder of applause from the Bagdad Showroom above our heads heralds the arrival of Mr. Excitement himself, fresh from the first-show triumph. He bursts through the dressing room door, trailed by Peaches and a cloud of Paco Rabanne. Sweeping through the outer dressing room and into his inner sanctum, Wayne hands Peaches his tuxedo—a glossy black number with a relatively subdued (for Vegas) pattern of sequins sewn around the shoulder and chest. He takes off the massive turquoise-and-silver Indian belt with the fierce eagle embossed upon it (a gift, I was told, from his fellow Cherokee-tribe descendants). He splashes on some fresh Paco Rabanne, slips into the luminously well-worn crushed-black-velvet smoking jacket he prefers for relaxing between shows, and emerges—the King of the Strip—to greet his loyal subjects, guests, and visitors.

I have to admit I was surprised by Wayne’s physical presence. All I’d had to go by before now was a truly awful eight-by-ten glossy head shot that arrived with his press kit before I left for Vegas. It’s the same basic shot that’s seen blown up billboard-size all over Vegas and all over the Aladdin. The still is a badly engineered attempt to bring out Wayne’s putative resemblance to Erroll Flynn, part of his campaign to land his dream role: the lead in the feature film of Flynn’s autobiography, My Wicked, Wicked Ways. But the resultant photo—complete with pencil-thin ’stäche and flashing wedge of white teeth—makes poor Wayne look like an overfleshed, stage-gigolo parody of Flynn.

Which is why his actual presence comes as such a surprise. He’s far more youthful, vital, thin, and indeed Flynn-like, in the flesh than the terrible embalmed-Erroll still suggests. And he’s a big, rangy guy— six foot three, with broad shoulders and a muscular frame.

Wayne likes to talk about his body. First he tells me how he built himself up doing weight training with Steve Reeves. How he dropped a hundred pounds using a “Caesar salad diet” of his own devising. How he got his black belt in karate.

He also likes to show his scars. From the days before he transformed himself into a tough guy. “Look here,” he says, pointing with his index fingers to the ends of his eyebrows. “Look at these scars.”

I look closely and see some fine lines that look like laugh lines, but no scar tissue. Am I looking in the right place?

“I got those scars when I was a kid in Arizona,” he says. “I was half Indian, and there was a lot of prejudice—they’d serve a black man in some places but not an Indian. So there were a lot of fights.”

And that was even before he started making hit records in a girl’s voice. As he says of that strange, sexually indecipherable tone in which he sang “Danke Schoen”: “I went to bed one night thinking I’d got the number-one hit on the charts, and I woke up with the whole world thinking I was a German girl.”

And what about his voice now? It’s nothing like that eerie, vaguely Teutonic, almost hermaphroditic wail. Imagine a husky, laid-back, low-key, good-ol’-boy, southem-frat-rat, beer-brawl drawl and you get an idea of how impeccably macho Wayne Newton sounds now as he asks me to join him, his lawyer, and his longtime associate Mark Moreno, Lola’s manager, for a confab about the complex extortion conspiracy he’s been the victim of—according to the indictment entitled U.S. v. Guido Penosi, aka Bull.

Over plates of crunchy fried zucchini at the Aladdin’s highpriced “Continental” restaurant (called II Continentale), Wayne fills me in on the terror-filled days that followed the Frontier Hotel punch-out.

The death threats he started getting after whipping the two wise guys weren’t aimed just at him, but at his child, he says: “I’d get calls in the morning telling me the exact route my five-year-old daughter was taking to school that day. The authorities said they couldn’t do anything but wait. This wasn’t me, this was my daughter. So I got Guido’s phone number. And that was it. The threats just stopped.”

“Then they started coming after me,” Mark Moreno says. “I’d get calls saying, ‘Be real careful when you start your car this morning.’ And worse.”

“So I gave Mark Guido’s phone number,” says Wayne.

“Same thing, those calls just stopped,” Mark says.

Just who was this Guido, aka the Bull, whose phone number came in so handy? According to Wayne’s testimony before the Nevada State Gaming Board, he first met Guido when he was a teenager singing at the Copacabana in New York City:

“He came in and sat in front of the stage and waved a hundred-dollar bill and asked me to sing a song. I did the song and refused the money, which astonished him. Then I ignored him the rest of the night and the next night he… sent a waiter so that he might have an audience and he asked me why I refused the money. And my answer was that I get paid for what I do, and he was astonished, stating that I was the first entertainer that ever refused money from him. From that point on he would come in various nights with groups of people and take bets on the fact that no matter how much money he held up I wouldn’t take it.”

“Did you know that he is a purported member of the Gambino organized-crime family?” a Gaming Board member asked.

“No sir, I did not,” Wayne replied. Still, there was that phone number. Both Wayne and Mark used it, and it seemed to have gotten results.

When I tell people I personally sat through twelve Wayne Newton shows in ten days, I am met with curious stares and a certain amount of incredulity.

Wayne and Mark are disarmingly forthright about calling in someone who—they must have realized—would not use the same diplomatic tactics as, say, Cyrus Vance in settling their problems. When the talk returned to Vegas chitchat and the name of a mutual friend who was having some problems came up, one of them joked, “We ought to give him Guido’s number.” “Yeah, I still have it,” said the other. The matter was treated so lightly that I was tempted to ask for Guido’s number.

Yet Guido’s phone calls were no laughing matter to the federal grand jury in New Haven that indicted him and his Connecticut-based cousin, the late Frank Piccolo (blown away by carbine fire three months after the indictment came down), for extortion conspiracy. The Feds, who had apparently been tapping calls between the cousins, alleged that after Guido the Bull got the death threats against Wayne and Mark called off, he and Frank conspired to use this favor to lean on Wayne, Mark, and even Lola to extort assets from them, including—from Wayne—a hidden interest in the Aladdin Hotel Casino.

Although the indictment makes clear that Wayne was a victim of, rather than a participant in, the alleged conspiracy, and although a grand jury eventually acquitted Guido, there’s a lot more at stake here for him than legal niceties.

There’s Wayne’s prospective political career. His attorney in the extortion case, Frank Fahrenkopf, also happens to be Republican State Chairman of Nevada.

The talk about Wayne’s senatorial prospects is no mere PR puffery, Fahrenkopf avers. Wayne’s a hero to the working people in Vegas—he went to bat for the bartenders and waiters when Summa Corp. tried to cut out their dinner break; he does benefits for cabdrivers and charities; he could be a serious contender for a Senate seat should Laxalt move up to Vice-President or higher. Fahrenkopf has heard Wayne deliver stunning political speeches, he says; he’s convinced the charisma of the Midnight Idol can be transferred from the showroom stage to the political arena.

But the suggestion of “mob connections” could destroy that dream. Wayne’s got to keep himself clean if he wants to join the likes of Donny Osmond from neighboring Utah, who is also reported to be aiming for a seat in the nation’s great deliberative body. If it were ever found that Wayne did cede a hidden interest of any sort to the Bull, Wayne could be not only out of politics but—just like the ill-fated previous owners of the Aladdin—out of the casino business too.

Tonight, however, here in the flickering candlelight of II Continentale, Wayne turns to me, looks me in the eye, and in his deepest, huskiest, most sincere voice swears, “They never got a cent out of me.”

Figuring Out The Show

When I tell people I personally sat through twelve Wayne Newton shows in ten days, I am met with curious stares and a certain amount of incredulity. But a dozen shows at a stretch is nothing from the perspective of veteran acolytes of the Wayne Newton cult.

The next afternoon Mona Matoba introduced me to a fellow named Gary from Alberta, Canada, who claimed to have gone as high as two hundred Wayne shows a year for several years “before I tapered off to about fifty a year for the past ten years,” he told me. But he’s not unique, he said; he knows of many others still going as high as the hundreds every year.

And then there’s the extraordinary story of Gary’s son. Get this: He came to Vegas on his honeymoon and managed to take his bride to thirteen Wayne shows in fourteen nights.

Of course, you don’t have to go to The Show (as it is reverently referred to) twelve or thirteen times to see how successful it is. You can listen to Wayne’s press agent rave about it as a moneymaking phenomenon:

“The man makes a million dollars a month from that show alone. Two shows a night, seven days a week, forty weeks a year, and for fifteen years never an empty seat. He’s the biggest money-maker in the history of Vegas. Nobody has drawn like that week in, week out. Not Elvis, not Sinatra. There’s just no comparison.”

But to figure out how Wayne accomplishes this, you have to study his act carefully. After a dozen shows I began to see how shrewdly he’s incorporated two key concepts of Vegasness into his act. At the heart of Wayne’s mesmeric mastery over his audience is the notion of Suspending the Rules and his invocation of the Summit Meeting myth.

People who come to Las Vegas leave the safety of their homes and bring their year’s savings to a precarious place perched in a desolate landscape that refused to support even vegetable life without massive infusions of Teamster loans to pay for the air conditioning. They come to place themselves under the dispensation of the laws of chance rather than those of God or man, to squander their time and money on things that are against the rules back home: gambling, prostitutes, drinking at dawn. There are no clocks on the wall: the laws of time are suspended along with those of morality.

They don’t expect to get away with it; they don’t expect to win. They expect to lose money but to come home with something more precious: an experience of the borderline, an adventure, a frisson of danger, a brush with the frontier ethos in which life hangs on the next card, anything can happen, and time doesn’t matter.

It’s a point—his Vegasness—on which Wayne is particularly sensitive. The only time he displayed a flash of anger at me was when I brought up the Vegas factor.

When it comes to the showrooms of Vegas, that myth of Suspending the Rules got its start in the legendary Summit Meetings of the early Sixties, those clamorous convocations of top-line talent— Frankie, Deano, Sammy, Joey, Shecky, Rickles: the Rat Pack regulars—who used to cavort onstage in the Copa Room at the Sands. Nobody knew who was starring or who’d drop in—Deano would stagger in on Sammy and take a call from Frank in El Lay, who’d drop everything to fly over the Sierras and pop in around dawn, while the action was still hot and heavy.

And of course the composition of the audience was part of the special chemistry of the Summit myth: at ringside you’d have the Hollywood high rollers, the Vegas heavyweights, gangsters, and men of respect, like Sam Giancana, side by side with swinging politicians like the Kennedy brothers, Rat Pack buddies like Peter Lawford, starlets, and swinging party girls like Judy Exner, who knew them all. This heady fusion of ozone, alcohol, and the hip and the famous was so propulsive that some of the shows just seemed to keep on going for weeks on end and never stop; the guys onstage would really hang loose, truly bare their souls—there were no rules.

It’s all over now, of course. The carefully planned “courtesy drop-in” has replaced the careless and spontaneous starbursts of legend. Vegas—the place itself—has become corporatized, the shadowy gangster glamour of hidden interests giving way to Holiday Inn, Hilton, Ramada, and other clean-cut-conglomerate ownership—at least along the Strip. High-priced “star policy” entertainment is on the decline, supplanted by the cheaper-to-produce topless “revues” that run forever; things have really begun to be run by the rules, and Las Vegas is fast becoming little more than an elaborate theme-park resort: Gambling Land.

From the very opening minutes of his act Wayne begins playing on the expectation of something special happening, the dream that tonight some magic suspension of the rules is in the offing—the ultimate unpurchasable Vegas experience.

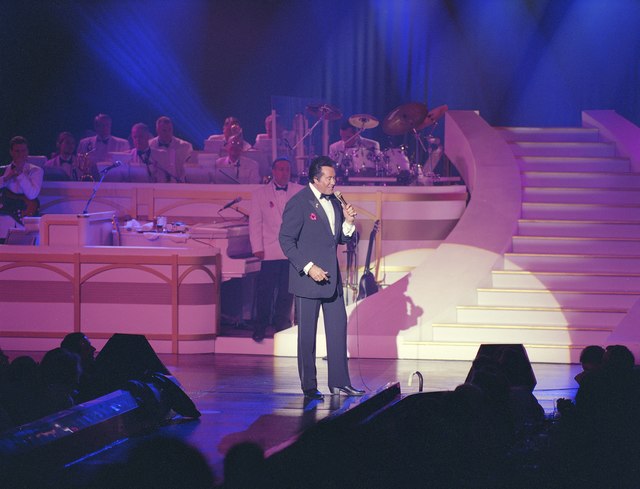

Backed by his huge forty-piece brass-and-strings orchestra, he’ll begin with a couple of up-tempo opening numbers—a Wayne Newton cover of a Frankie Valli cover of Little Anthony and the Imperials’ “Out of My Head, ” and an eerily accurate Elvis-like “Suspicious Minds.”

Then, with the audience still cheering, he’ll grab the mike and goad them on with a little jiving, to this effect:

“Wow, you’re hot tonight. You keep that up and we’ll keep on goin’—hell, another fifteen minutes.”

Audience gives a little nervous laugh— the short length of many shows is a controversial subject in Vegas, with many big-name headliners notorious for flying in for six-figure engagements and actually doing about a half hour of their greatest hits each night.

“Okay,” Wayne says, continuing this teasing rap, “how about an hour?”

Not much response. What’s he getting at here?

“Hour and a half?”

Cheers and scattered yells.

“Two hours?”

A roar of approval.

“And if you really honestly and truly want to bug the casino—”

He pauses. Gets whoops and hollers of approval. These people have been losing their life savings to every casino in town.

“—you is lookin’ at the head bugger in charge. Three hours would really irritate the craps out of them.”

Another roar of delight.

That’s Step One. Then it’s back to singing up a storm—a saloon-music medley, a soul-gospel medley, a Waylon-and-Willie-C&W medley, and, for the late show, a genuinely impressive rockabilly medley featuring an impeccable cover of “Johnny B. Goode,” complete with Chuck Berry duck walk, and a genuinely stirring version of “Born to Lose.”

Then it’s time for Step Two: After playing medley after medley of medleys, Wayne stops the tumult and noise, turns to the audience, and, with husky-voiced sincerity, tells them, “You know, sometimes we get an audience that’s so special we just throw away all our plans, take a right tum, and keep on going. . . ”

Or he’ll say, “You know, I don’t often do this next song; it requires a special kind of group, a special kind of mood. So let’s do it.” And the lights will dim and Wayne will launch into his grand ultra-serious production number of “MacArthur Park,” complete with emotion-choked narrative sections, dry-ice fog machines pumping away like mad, and—gasp—right in the middle of the interminable song, a gleaming Mylar glitter curtain that is meant to simulate rain dropping down dramatically.

Or he’ll introduce a bluesy number with his sultry backup singer Avis by saying, “I knew this was a special group tonight. The Definitely Dirty Group. And we’re gonna do somethin’ hot just for you.”

Having established the illusion that there’s something extremely special going on tonight, some magical show-biz chemistry between himself and his audience, unique to this evening, unique perhaps to his three decades in show business, something so great that he’s ready to keep singing till dawn or till his throat gives out, he then proceeds to Step Three: creating the illusion that the rules have already been violated.

Inevitably it takes place during a rousing up-tempo number like “Waitin’ on the Levee,” which displays Wayne’s playing on the banjo, the electric guitar, the electric fiddle, in quick succession. In the midst of all this furious display of multiple musical virtuosity Wayne will just happen to glance at his watch. Suddenly he’ll assume an expression of total terror, knock his knees in mock shock, and say in a high-pitched voice that suggests a panic-stricken Elmer Fudd: “Oh boy. Ooooh boy. You know we are so far overtime that—”

Whistles and cheers interrupt him.

“—that it just don’t matter anymore.”

Roars of triumph from the crowd. We beat the casino tonight. What a night— wait’ll they hear about this back in Toledo.

At which point Wayne will snatch up a fiddle or banjo or whatever instrument in his forty-piece backup orchestra he’s yet to play, saw or strum away like mad for a few more minutes, and then begin the introduction of the bandleader and featured players that will bring the show to an abrupt close.

Everyone leaves The Show feeling totally satisfied, thinking how hip, how simpático, how special the whole evening was; how they’ve been present at one of those rare moments when the rules went by the board; how Wayne drove himself past his own limits, knocking himself out just for them. And yet each of the twelve shows I saw started and ended at the exact same time on the dot.

It takes a shrewd and talented showman to pull off an illusion of this sort night after night, show after show. I began to wonder after a while whether everybody really bought this illusion or whether at some point they decided to buy it. They wanted to be able to go home to Arizona or New Jersey, wherever, and tell their neighbors at the mall how one night in Vegas they helped create some memorable show-biz magic. The emperor’s new set of clothes looks even more grand to those who believe they’ve had a hand in the tailoring job.

Through the Valley of Fire to a Rendezvous with the Son of Aramus and the Son of the President

They call it the Valley of Fire, and it’s a forest of blazing red-rock peaks rising like ruined skyscrapers out of the flat, broiling desert floor. Forbidding place just to look at, but damned if the copter pilot isn’t flying not over or around those jagged peaks but right into the midst of them. He’s acting as if this were Nam or something and we’ve got to fly down through enemy fire to rescue the wounded. We’re weaving in and out of those towering red stalagmites, and beautiful as they are in the abstract, I’m certain I’m going to end up a smoking ember on the floor of the Valley of Fire any moment now. The copter pilot seems determined to prove he’s no amateur at the stick, that he’s got the copter version of the Right Stuff.

The copter pilot is Wayne, of course.

We’re on our way up to his Arabian horse-breeding ranch in the desert north of Las Vegas. Wayne seems to know how to surf along the hot-air eddies that boil up off the desert. He flies a plane like a pro, I’ve been assured. But still . . . there were those stories he told me last night, the close brushes with death—one while piloting his plane, running out of fuel, unable to get his landing gear down; the other, a total helicopter stall-out he only managed to pull out of a hundred feet before ground zero. And then there was the picture of Wayne I saw at the ranch with a fellow horse-breeding enthusiast and flying buddy—the late Thurman Munson. But we’re descending safely now, and next to the corrals, the barns, and the ranch house there’s a strange sort of vehicle gleaming in the sun.

It’s the longest RV I’ve ever seen in my life. From up in the copter as we approach Wayne’s stud ranch it looks like a shimmering Supertrain. Another macho status symbol of Wayne’s? No, it’s the land cruiser bearing the First Son, Michael Reagan, his wife, a couple of Calvin-and-Gucci-clad friends, and a black-shoed contingent of secret-service men.

Mike Reagan—an old showbiz/politico pal of Wayne’s— says he’s looking for a new job, but judging from his relaxed manner and the regal appointments of this magnificent cross-country RV, he doesn’t seem to be looking too hard.

Wayne leaps lightly out of the copter in his Ultrasuede chaps and, like a proud father, orchestrates a showing by his stableboys of his prize Arabian stallions. Indisputably some of the most perfectly beautiful living creatures ever to trot the face of the earth, they are justly famous within the elite world of purebred-horse breeders. The best money can buy. I wondered if his Arabian obsession was just another expensive more-macho-than-thou hobby, like his huge fleet of perfectly restored Duesenbergs and other antique cars.

But no, there’s something more going on between Wayne and these horses—at least between him and one of them, the pride of his stable, the fabled son of Aramus. The stableboy brings him out, a snow-white steed whose very presence inspires awe. Up until now all of us—the First Son, the Calvin-clad couple, even the secret-service men—have been nuzzling and petting these priceless specimens. But not the son of Aramus. We keep a reverent distance while Wayne tells us his tragic and triumphant story.

Once upon a time Aramus—the father—was the most famous Arabian horse of them all. A renowned sultan of show business brought him to the desert north of Las Vegas, a desert whose searing heat and shimmering expanse suited his Arabian blood splendidly, and the steed was worshiped there as a wonder of the world. But then sadness struck: a careless vet stuck the wrong needle into the horse, causing a painful—and fatal—allergic reaction.

The sultan of show-biz city was heart-struck and embittered. He decreed that no horse ever be permitted to enter the stall once occupied by the departed Aramus. Nothing could console him for the loss. Nothing except perhaps this one posthumous colt, the last son of Aramus. Not that there was anything about the colt to indicate its proud parentage. Far from it: the stable hands laughed at him, an ugly-duckling, brown-and-gray-dappled parody of the snow-white perfection of his father. But Wayne, the brokenhearted sultan, thought he saw a glimmer of something about the son and lavished the kind of attention on him that, from all appearances, he did not deserve.

Something prompted Wayne to put the colt in his famous father’s stall, kept empty since the tragic death. When Wayne starts telling us about it, he gets a kind of misty, mystical look in his eye. Even the secret-service men, spotting no hostile Indian threats to the First Son on the horizon, seem to be transfixed by the feeling Wayne puts into the story.

Something spooky began to happen to the colt, says Wayne. The color of his dappled coat began to grow lighter and lighter until it was transformed into the pure milk-white translucence of his departed father. He filled out to his father’s Platonic perfection of conformation. It was almost as if the spirit of the father had inhabited the stall and been reincarnated in the son. The new pride of the stable seemed touched with his father’s noble magic and began winning all the same prizes for perfection his father had won. A shot of his sperm now goes for a healthy five-figure fee.

Aside from that last commercial consideration, I felt that in listening to Wayne tell the story of the Ugly Duckling Stallion I was hearing him talk about his own transformation from show-biz freak into world-class champion entertainer.

The Last Legacy of Howard Hughes

But there’s one thing missing from this parallel. Who in Wayne’s case was the paternal figure who saw promise while others were still chuckling at the ugly duckling? Who watched over Wayne and selected him for a stall of destiny?

Would you believe Howard Hughes? Walter Kane does, and Walter Kane should know. He was Hughes’s chief entertainment aide from the late Twenties, when the tycoon took over RKO Pictures, to the time of Hughes’s notorious invisible penthouse reign over Vegas in the late Sixties, when Kane became director of entertainment for Hughes’s Summa Corp.

It’s near midnight, the night after the copter trip to the stallion ranch, and we’re cruising north on the Strip from the Aladdin to the Sands in the plush, insulated interior of a cream-colored Summa Corp. stretch Continental.

The occasion: Closing night at the Copa Room of the Sands. After the midnight show tonight the legendary cabaret, site of those Summit Meetings that are the central myth of Vegasness, will be gutted.

Walter Kane and I are accompanying Wayne, who’s agreed to do one of those carefully calculated surprise drop-ins— the pale descendants of the genuine Rat Pack hang-loose spontaneity of legend.

It’s a particularly melancholy moment for Walter Kane, who was present at the opening night of the Copa Room thirty years ago, ensconced in glory at the right hand of Howard Hughes, at a ringside table full of starlets. And now, as he sees in the death of the Copa Room another milestone in the decline of authentic Vegasness, Walter conjures up for us the ghost of the late, great, invisible emperor of Las Vegas and confides to me the strange affinity Howard Hughes had for Wayne Newton.

It came at a crucial time in Wayne’s career. Hughes had just moved into town and Wayne had just moved out of adolescence. Hughes was trying to put a Mr. Clean front on the unsavory reputation of Vegas practices, and Wayne was trying to make the transition from novelty act to adult entertainer.

According to Walter, Hughes took a keen interest in the kind of entertainment being offered at the casinos he’d been buying up, and paid special attention to

Wayne. One can imagine the half-mad mogul naked and bedridden, fearful of germs and fallout and all of modem life, taking comfort from tuning in to Wayne crooning “Red Roses for a Blue Lady.”

Soon the invisible emperor began in his own peculiar way to communicate with Wayne. Up in his Desert Inn suite he’d drill one of the handful of Mormon attendants on messages he wanted memorized and delivered to Wayne.

“What happened,” Wayne tells me, “was that a guy would appear and he’d say to me, ‘Mr. Hughes wants you to know he knows what you’re doing and he’s proud of the kind of entertainment you’re representing. He’s happy that you’re a member of his family!’”

Word got around that the unpredictable new godfather buying up Las Vegas had adopted Wayne as a kind of special godson. Suddenly entertainment directors all over town were seeing Wayne as a serious major talent and bidding up his price. Everyone began to praise the invisible emperor’s new singer as the pride of Las Vegas. Hughes had put him in his Stall of Fame.

“I think he saw a lot of similarities between himself and Wayne,” Walter Kane tells me.

There’s a certain appropriateness to it all. As it was with Hughes, upon whom so many people projected their fantasies and who, by never appearing, never contradicted those fantasies, so it is with Wayne’s show-business “genius.”

Cloaked with the reputation of being the thing to see in Las Vegas, the peak of entertainment, Wayne provides enough razzle-dazzle, noise, illusion of spontaneity, virtuosity, sentimentality, and Vegasness for people to come out saying, “That was entertainment,” and mean it.

Security and Insecurity at Casa De Shenandoah

I have to admit I approached the high spiked gates of Casa De Shenandoah with a certain amount of wariness.

Even before the various sets of death threats beset him and his family, Wayne was notorious for his mania for security measures. Yet I found not the armed camp I was expecting but a green and gentle peaceable kingdom—an almost childlike fantasy world where peacocks stalk amongst the wallabies and swans drift along ponds lined with weeping willows.

After winding my way along curving brick drives through stately lawns, I find Wayne waiting for me at the main entrance of the Big House.

Some have compared the, well, dramatic architecture of Casa De Shenandoah to that of Tara. But Wayne bridles when I ask him if he had Gone with the Wind in mind when he built his house.

“Well, of course every southern boy wants to grow up and live in a mansion,” he concedes. “But I designed it myself. There are always people who will try to put something in a category and say this is a replica of Tara, but it’s not.”

And he’s right, of course: it’s not like Tara. Try to visualize a southern mansion that combines influences of the White House’s north portico and the main entrance to Caesar’s Palace and you begin to get the picture.

The room we’re in—Wayne’s den—reflects the persistently odd mix of interests that has marked Wayne’s life. High school mementos include prizes for raising and breeding pigeons plus prizes for being the top cadet in his high school ROTC unit. And amid the three gold records, the Presidential letters, the awards for charitable work, there are these two odd petrified objects on and in the fireplace.

“This is a petrified clam I found on top of a mountain in Elko, Nevada,” Wayne tells me, evidence that what was once ocean-bottom muck now rests on the highest peaks in the West.

And then there’s the large rocklike object resting inside the fireplace. “I found it out in the desert, took it to some scientists, who told me it was petrified dinosaur crap,” he says proudly.

As he identifies these delights of the desert for me his wife, Elaine, enters to announce that Kirk Kerkorian (onetime tycoon rival to Howard Hughes for top man in Vegas and still owner of the MGM Grand) is on the phone.

Wayne’s wife seldom appears at the Aladdin for the shows. A petite Oriental beauty (part Hawaiian, part Vietnamese), she avoids the daily grind of backstage schmoozing, preferring to reign over this quiet realm and raise their daughter, Erin.

Wayne is off the phone with good news: “Mr. Kerkorian,” as he respectfully refers to the tycoon, “has offered me the use of his personal DC-9 to carry the show out to Atlantic City.”

Wayne is doing a weekend at Resorts International there and then setting out for a nineteen-city tour of the East and Midwest. The national tour of big arenas is part of a grand strategy he has devised to transcend what he sees as a misperception of Wayne Newton as a creature of Vegasness, whose success is an aberration peculiar to the Nevada desert—like, say, that dinosaur dropping.

It’s a point—his Vegasness—on which Wayne is particularly sensitive. The only time he displayed a flash of anger at me was when I brought up the Vegas factor. “Why is it,” I asked him, “that some people in show business make it big in other places but can’t cut it in Las Vegas, while others make it big in Vegas and are, uh, less big elsewhere? Is there something about Vegas that—”

He interrupted me, glaring: “I don’t know of anybody who makes it big in Vegas and is less big elsewhere. Name one.”

I realized the seriousness of my slip and sidestepped the challenge.

“Well, I don’t know, uh, I guess Cher, now, or uh—”

“Well, let me tell you,” Wayne lectures me, “Vegas is truly a barometer for certainly the country and maybe the world—a lot more so than anyone ever wants to believe. This is the foremost battleground for entertainment in the world. And there are still only five or six people in the world who can sell out every show.”

He returns to the subject later. “When people want to put Wayne Newton down, they say, ‘Okay, he’s big in Vegas but that’s all!’ Or, ‘He does a Vegas act!’ And I always say,’’ says Wayne, waxing indignant, “what is a Vegas act? I mean, who comes here? Is it all locals? Do they fill the showrooms thirty-six weeks a year, two shows a night, seven nights a week? No, of course not. It’s people from all over the world! But they don’t want to recognize that.”

I ask Wayne about his sensitivity to insults. Does he still feel the effects of the years of ridicule—the racial insults to his “mixed blood” and the Wayne Newton jokes that slurred his masculinity? Are there scars from all that?

“I think probably,” he says. “Mental scars as well as physical. I mean, during your formative years, when you’re as far out in left field as I was, being an Indian. Fat. Doing a TV show when you’re twelve years old. I mean, I had every reason in the world why they should be picking on me. And it left its lessons with me. I think I’ll always carry those scars. I think if anything I’m far too sensitive for my own good.”

“You mean thin-skinned?” I ask.

“Very. Very. And it might have to do with the fact that I read people a lot better than most, so most of the time they don’t have to say things that hurt me. I pick up on what they’re thinking,” he confides. “Now, that might sound terribly insecure, but I’m not insecure, okay?” he adds.

Okay. But then he tells me the story of How He Sacked the Sleepy Violinist, which he lets slip out as a corollary to his explanation of the Meaning of Life.

Wayne is showing me a small statue on a table in his den, which gets him in a philosophical mood. The statue, a caricature, depicts Wayne in full Emmett Kelly-like clown makeup, the mask he painted on for a long dramatic monologue called “The Clown,” which he used to do twice nightly in earlier versions of The Show.

“I decided to do it in clown form,” Wayne says, “because as Wayne Newton it would not be believable. But the minute you put on that clown white and the red nose you can be anybody. The story of ‘The Clown’ is literally the story of life and certainly that of the performer. It’s that trained animal out there onstage: he goes through the hoops, no matter how many troubles, how difficult it’s been for him, the public should never know. But the minute you don’t go on, the minute you cop out, is the beginning of the end. If you don’t go on, that kind of fear and all the things you give in to—it’s devastating, it’ll destroy you . . .”

“Do you go out there feeling the audience is ready to pounce on you?” I ask.

“The audience will pounce on you when they feel violated,” Wayne says. “And when I say violated. . . . I had a scene on closing night that you don’t even know about yet. I fired a violinist halfway through the closing show. What happened was, he was sitting there front row—a brilliant violinist—and I was about a quarter of the way through the show and he was sleeping. And when he raised up his eyes I looked at him and I went”—Wayne makes an admonishing gesture to his eyes to the effect of “Keep them open”—“and he looked at me and he went”—Wayne holds up his middle finger to his nose in an unmistakably hostile gesture.

“Now, I can’t tell you how hard I had to try to contain myself,” Wayne tells me. “Had I blown up at him in front of that audience there would have been a damper on the night. I couldn’t have overcome it. They wouldn’t have been able to understand why I was angry. To them it would have been, here’s the star picking on a lone violinist, this nice little old man sitting there. So I went over to my bandleader just before I started the blues number. I told him, ‘Get that guy off the stage now.’ And he sat over there in the wings and I let him go when I got off.”

Now it happened that I had been wandering around backstage during this particular show. I remember coming upon that lone violinist sitting on a metal folding chair near the fog machines, staring blankly ahead, waiting for the ax to fall. It might be the last time he ever worked in Las Vegas. And why was it Wayne had to fire him? It wasn’t his own thin skin, it was the audience that was being violated. He fired the guy for the little people out there.

We take a final stroll around the grounds of Casa De Shenandoah before I head back to the Strip.

We pet Wayne’s wallabies, admire the willows around the lily ponds, the whole illusion of southern comfort set amid the coyote-ravaged wasteland of the Nevada desert. Wayne seems the contented squire, the philosopher-king, secure in a world created to his specifications.

And in fact it may be that the world has come round to Wayne. The growing popularity of “Vegas soul,” his kind of music— Barry Manilow, Neil Diamond, Kenny Rogers, the MOR/AOR crossover demographic —is serving to make what Wayne does musically seem less a deviation than the mainstream. The baby-boom generation that grew up with Wayne is reaching a sentimental age now. Anyone who’s ever felt ridiculous, anyone who’s ever been ridiculed, can appreciate Wayne’s getting the last laugh on all those Wayne Newton jokes.

Everyone leaves the show feeling totally satisfied, thinking how hip the evening was.

Vegas soul. Don’t underestimate it. Not if you want to understand Vegas, the state of Nevada, the state of mind of the millions who worship Wayne. Because if you listen to Vegas soul, those classics that persist in every Vegas act—“Lady,” “Feelings,” “MacArthur Park, ” “I Cried a Tear, ” “Little Green Apples, ” “Out of My Head, ” you know the ones—you realize Vegas is not the tough gangster town, not the sin city, the seductive illusion used to lure conventioneers. It’s syrup city, soppy city, woozy, sentimental city.

People go there for nostalgia: to help them make it through the night, to cry a tear for the good times they’ve lost. You can see it if you sit in the Bagdad Showroom during Wayne’s act, the youngish middle-aged couples leaning together, smiling through the tears, dreamily melting into the sea of sentiment washing over them, knowing they’ll “never have that recipe again.”

Wayne has that recipe. And he’ll survive the Guido the Bull associations. They may even turn out to be good for him—give him the mystique, the is-he-or-isn’t-he gangster glamour that’s worked so well for Sinatra; prevent him from going the goody-goody Senator Donny Osmond route.

As Wayne walked me to my rental car, I looked back at the mansion and the lawns, the perfect picture of serenity and security.

“You’d never dream you were in Vegas, would you?” Wayne says grandly as he gestures to the pastoral perfection of his plantation home.

But you would.

[Featured Image Todd Eberle via Art Institute of Chicago; picture of Newton via Wikimedia Commons; casino entrance by Patty Carroll]