“The truth is, those are not Soviet troops in Afghanistan. They’re ABC technicians, sent by Roone, dressed in Russian uniforms.” — Don Ohlmeyer

Don Ohlmeyer wishes.

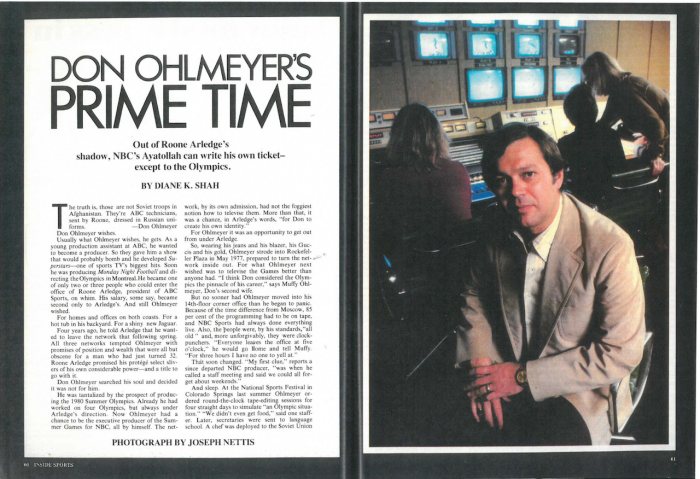

Usually what Ohlmeyer wishes, he gets. As a young production assistant at ABC, he wanted to become a producer. So they gave him a show that would probably bomb and he developed Superstars—one of sports TV’s biggest hits. Soon he was producing Monday Night Football and directing the Olympics in Montreal. He became one of only two or three people who could enter the office of Roone Arledge, president of ABC Sports, on whim. His salary, some say, became second only to Arledge’s. And still Ohlmeyer wished.

For homes and offices on both coasts. For a hot tub in his backyard. For a shiny new Jaguar.

Four years ago, he told Arledge that he wanted to leave the network that following spring. All three networks tempted Ohlmeyer with promises of position and wealth that were all but obscene for a man who had just turned 32. Roone Arledge promised his protégé select slivers of his own considerable power—and a title to go with it.

Don Ohlmeyer searched his soul and decided it was not for him.

He was tantalized by the prospect of producing the 1980 Summer Olympics. Already he had worked on four Olympics, but always under Arledge’s direction. Now Ohlmeyer had a chance to be the executive producer of the Summer Games for NBC, all by himself. The network, by its own admission, had not the foggiest notion how to televise them. More than that, it was a chance, in Arledge’s words, “for Don to create his own identity.”

For Ohlmeyer it was an opportunity to get out from under Arledge.

So, wearing his jeans and his blazer, his Guccis and his gold, Ohlmeyer strode into Rockefeller Plaza in May 1977, prepared to turn the network inside out. For what Ohlmeyer next wished was to televise the Games better than anyone had. “I think Don considered the Olympics the pinnacle of his career,” says Muffy Ohlmeyer, Don’s second wife.

But no sooner had Ohlmeyer moved into his 14th-floor corner office than he began to panic. Because of the time difference from Moscow, 85 per cent of the programming had to be on tape, and NBC Sports had always done everything live. Also, the people were, by his standards, “all old” and, more unforgivably, they were clock-punchers. “Everyone leaves the office at five o’clock,” he would go home and tell Muffy. “For hours I have no one to yell at.”

That soon changed. “My first clue,” reports a since departed NBC producer, “was when he called a staff meeting and said we could all forget about weekends.”

And sleep. At the National Sports Festival in Colorado Springs last summer Ohlmeyer ordered round-the-clock tape-editing sessions for four straight days to simulate “an Olympic situation.” “We didn’t even get food,” said one staffer. Later, secretaries were sent to language school. A chef was deployed to the Soviet Union to teach the Russians how to prepare decent food for the NBC staff of hundreds. After nearly three years, Ohlmeyer was finally thinking he might pull off the greatest sports spectacular ever. Then on January 20, the phone rang in his suite at the Beverly Wilshire Hotel. “Don,” said a voice from NBC, “tomorrow on Meet the Press, Carter is going to call for a boycott of the Moscow Olympics.”

For nights, Ohlmeyer would lay awake, thinking that surely something would happen before the February 20 deadline.

On February 20, Ohlmeyer and Muffy were on an airplane when the pilot came on to announce that the State Department had just reiterated the President’s stand. Muffy looked at her silent husband. “Say something,” she said. “What do you want me to say?” The teeth clenched. “What do you want me to say?”

March 24. At the NCAA championship game in Indianapolis, which NBC was televising, Ohlmeyer was asked if there was any significance to his red-and-white striped shirt and his blue sweater. He looked at his clothes and said: “Why, I’m just showing my loyalty to President Carter.”

At 35, Ohlmeyer has attained the power and lifestyle that most people only dream of. He lives on Fifth Avenue in one of New York’s most expensive apartment buildings, right next door to Dolly Parton. There is a country home in Connecticut—and a chauffeur to get him there. Last month, he sold his Jaguar and is about to sell his hilltop house in Bel Air, the one with the hot tub and the cold tub and the tennis court, because he and Muffy had just found a bungalow on the beach in Hawaii. Not that Ohlmeyer spends much time in any of his three homes, even if they do contain 12 color TVs. He passed most of the winter in suite 779 of the Beverly Wilshire, to be near the filming of his first TV movie, The Golden Moment. Often, he can be found in the first-class section of a 727, en route to a major sporting event.

He has total creative control; he can put on the air whatever he wants. He can produce eight non-sports specials, four of which he owns the rights to. The first-year salary was reported at $400,000, with built-in escalator clauses for each succeeding year. Then there are the perks—the rent on the Fifth Avenue apartment and first-class travel expenses for Muffy. In all, it is estimated that Ohlmeyer made nearly $750,000 in 1979, and this year, depending on how the foreign rights to his movie do, he could clear a million.

He has two offices, in Burbank and in New York, with TVs, refrigerators and Betamaxes in each. His assistants are constantly on call. At production meetings, he draws two fingers to his lips and a fresh pack of Marlboros thuds softly onto the conference table. A drinking gesture produces a cold Tab. Recently, he was scheduled to look at a tape in a production house a block from NBC. The time was indefinite. He dawdled in his office, then impulsively reached for his coat. Outside his door, with her coat on, stood his assistant, looking like she was afraid she’d miss the next bus. In an industry where all an executive need do is push a button and up pops tape, Ohlmeyer pushes a button and up pops real life.

As executive producer of NBC Sports, he controls 450 hours of programming a year and a budget of $120 million. Ask the 110 or so people who work for him, and they’ll tell you he controls their lives. Before a production meeting in December, seven announcers, including Tom Seaver and John Brodie, waited outside his office. His door was closed. Finally someone said, “Is he in there?”

“Who?” asked Peggy Peters, Ohlmeyer’s secretary.

“Don.”

“Oh,” said Peggy. “You mean the Ayatollah. How would I know? I’m only one of his hostages.”

Donald W. Ohlmeyer Jr. grew up an only child in the Chicago suburb of Glenview. His father was a chemist, his mother the head of physical education at Glenbrook High School, and his earliest memory—he swears—was sitting on his father’s shoulders at a pep rally.

His upbringing was strict; early curfews and household responsibilities. “I always figured I could have made someone a good wife,” he says. “I really liked ironing.”

He also liked sports. At Glenbrook High he was a three-letter man and his abilities as a catcher excited Bradley University enough to offer him a scholarship. Instead, Ohlmeyer enrolled at Notre Dame, then reconsidered, and went to Bradley the next fall. “I only stayed one semester, though. I had grown up in a strict house and been to Notre Dame. At Bradley, I started smoking and drinking and the women wouldn’t leave me alone. I told my pledge father, ‘I can’t handle this,’ and went back to Notre Dame.”

First he majored in pre-med, only to switch to communications. Then he fancied himself a great actor, “but nobody appreciated me.” One semester he dropped out to play golf. He worked for a vending machine company, tested fire extinguishers, was an electroplater in a factory, bounced undesirables out of bars. “I guess you could say I didn’t have much focus in my life. For a while I sold insurance policies. I had no ambition.” Wrong. What he didn’t have was the direction for his ambition.

When he was in New York during his junior year, he marched into ABC and asked to see someone from Wide World of Sports. He was shown into the office of Jim Feeney, an associate producer, who was polite but firm. No, he told Ohlmeyer, he could not envision a Wide World segment about a sports car exhibition at Notre Dame. The next year, Ohlmeyer was playing pool in a bar in South Bend, when in walked Feeney, who was in town for a Notre Dame basketball game. Over the pool table, Ohlmeyer hustled him for a $25 job as an ABC go-fer.

That winter and spring, he ran around for ABC helping out at basketball games and the Indy 500. One day Howard Cosell, who had never met Ohlmeyer, received a phone call from an AP sportswriter from Indianapolis, who was a mutual friend. Would Cosell recommend Ohlmeyer for a permanent job? Apparently, Cosell did so, for he now says, “I take full credit for bringing Don Ohlmeyer to ABC.” Jokes Ohlmeyer, “Even though Howard recommended me, I still got the job.”

That June, as Ohlmeyer tells the story, he headed for New York with his first wife, Dassie, $100, a car that someone paid him to drive East and all of his possessions. “When I got to ABC I went crazy. I took one day off that first year. I used to sit in the editing room until 4 a.m., just watching. I knew right away I’d get totally caught up in it. I also knew it was probably going to wreck my marriage.”

Geoff Mason, executive vice-president for NBC Sports and Ohlmeyer’s contemporary at ABC, says of his friend’s early days: “When he got into TV, he knew immediately this was where he wanted to make his mark. And it was crazy. We were making good salaries, doing good shows and having so much fun, it was like stealing money.”

Less than a year after he was hired as a production assistant, he was promoted to associate director. Now he was working—and living—in the edit room. “He was so good at putting tape together,” says director Chet Forte, “that I used to make him do it over again—just to teach him a little humility.”

By the time the networks were elbowing each other to offer him million-dollar contracts, Ohlmeyer had established himself as the technical expert of the tube. When the Emmy nominations for sports programming were announced this year, Ohlmeyer couldn’t resist: “Did you see the headline in Variety? ‘Ohlmeyer 11—Roone 7.’ ” NBC won three of the 11, and Ohlmeyer one, personally, his eighth. Arledge now has 21. Says Forte, “I’ve been in the business 23 years, and Don’s the best producer I’ve ever worked with.”

Ohlmeyer thought he was more than just a good tape man. He knew what people wanted to see. No matter that broadcasters and sponsors were betting Superstars would be Superdud, Ohlmeyer went ahead. “To me, the concept was to show the gladiators without their helmets. I could see a father and son and the kid saying, ‘Dad, you’re a better bowler than O.J. Simpson.’ For women, the appeal was seeing athletes as human beings. But look, the show didn’t just happen. I made it happen. Five years of my life went into Superstars.”

Soon Ohlmeyer was producing Battle of the Network Stars and earning a reputation as the king of trashsport. His response: “So what’s so culturally enlightening about 22 men bashing skulls on Sunday afternoons?”

By the time he was 28, he was producing Monday Night Football, or as he called it, Brother Love’s Traveling Freak Show, and refereeing bouts in the booth among three of TV’s larger egos. Already, he had worked the Olympics in Munich, where in the aftermath of the murders, he sat in the control truck directing coverage for 18 straight hours, only to burst into tears when the network signed off. The horror of the event combined with the pressure of the job was such that today Ohlmeyer speaks of Munich only after a few beers. “Somehow that whole experience made a man of me.” He pauses. “It also made me a fatalist.”

It was about this time that Ohlmeyer realized his marriage was not going to work. They were expecting their third child and he was never home. Dassie would have parties and he would arrive late—or not at all. “Dassie finally decided there was more to life than what she had, and I decided I wasn’t a very good husband. The whole thing collapsed in 1975.”

While his marriage was failing, at work he was known as one of the few guys who could get the job done for Arledge. Ohlmeyer was the eager student and Arledge the master, but in many ways they were alike. Says Chet Forte: “Both love sports and entertainment. Both are extremely diplomatic. Like Roone, Don is the consummate politician. They both have tremendous professional judgment. And they both need to be the center of attention.” The only difference, Forte continues, “is that Roone expects it. He’ll walk into a room and wait for everyone to rush over. Don doesn’t expect the attention, but he’s so personable and outgoing, he gets it.”

In early 1977, Arledge attended the NFL owners’ meeting in Scottsdale, Arizona, and Ohlmeyer was just a step behind. He was there to sit beside Arledge at large dinners, to refill a glass at a cocktail reception, to lighten a conversation, or to steer his boss clear of a bore. Now he gets a certain satisfaction when Arledge phones and complains, “You’re impossible to reach. You never return calls.” And Ohlmeyer, laughing, answers, “And I learned it all from you!”

Ohlmeyer could not get rid of the doubts. Was he really that good? Or was it that ABC made him look good? What would happen if he didn’t have Arledge to guide him and the troop support of ABC’s exuberant youngsters who were making the network No. 1 in sports? While Arledge always paid Ohlmeyer his proper respect, Ohlmeyer respected ABC’s pecking order—he was No. 2. He had to leave, he had to find out.

Though his contract with ABC wasn’t due to expire until April 1977, NBC had quietly let it be known in December that it wanted him for the Olympics. By March, NBC was offering $400,000 a year. Bob Wussler of CBS jumped in with an offer to let Ohlmeyer independently produce entertainment shows—for $450,000. ABC wanted him to stay. “It was incredible,” says Ohlmeyer. “There was Roone offering me sports shows. Freddie Silverman was telling me I could do prime time. And Fred Pierce was talking money. And I’m sitting there, in awe of all of them.”

For weeks he agonized. He even drew up a list of pros and cons. One of the cons listed for NBC read: “Building—shitty.” Finally, it was a phone call from his former wife that settled it. “You’ve never turned down a challenge before. I think you’re afraid of failing. But anybody who’s any good has always come back from a failure.” So why would he be afraid?

“I left ABC because I didn’t know if I was any good as an individual,” he says. “Now I don’t ask myself that question anymore.”

“I’d rather be a shooting star than a constellation.”

Ohlmeyer shot to the top of NBC Sports. Within two months of joining the network, he was no longer just the man in charge of the Olympics; he was executive producer of NBC Sports. “I saw right away that if I didn’t get into the day-to-day operations, I wouldn’t be able to get the network where it needed to be for the Olympics.” Adds one NBC executive: “No blood was shed. Don simply came in and took over.” Arledge, now president of ABC News and Sports, says, “He feels he has to prove that he can do everything.”

So quietly did he seize control that almost nobody realized it until months later when the network officially made the announcement. Writer Larry Merchant, who was a producer at the time, recalls, “He was the guy who recommended I do NFL ’77. He was the guy who was always in the studio. He was the guy I started reporting to. Suddenly, I realized he was my boss.”

So did everybody else. “At first, people would shake,” recalls Peggy Peters. “They were afraid to say hello to him. Sometimes he would take people into his office and tear them apart. I would feel so sorry for them. But then I saw that the ones who stood up to Don got the respect. After a while, I learned how to stand up to him, too.”

During one live telecast, the equipment broke down. Ohlmeyer, who had been feuding with engineering management to upgrade their machines, was so furious that he made the announcer say over the air, “NBC engineering management is at fault.” This, in turn, outraged the engineers. According to one production man, “After that, we had to pacify a lot of people. Some engineers refused ever to work in sports again.”

Early on, he grabbed the director’s chair from Harry Coyle, the best baseball man in the business. As a cameraman recalls, “At one point, Don asked why a steal at second was covered from the centerfield camera and not from first base. Well, it’s obvious. Centerfield offers a better angle. Don was just asking, but for the rest of the game, Harry used the first base camera. The show was terrible. Afterwards, Don apologized and from then on he’s left the directing to Harry.”

Ohlmeyer was especially hard on the veterans. He had come in with fresh ideas and a new “look” for his shows, and he displayed little tolerance for the 20-year men who could not adapt. “In the truck he would get angry if someone made a mistake,” says a long-time NBC staffer. “He would shout, ‘That person will never work in sports again.’ I don’t think he actually fired anybody, he just buried them. He’d put them in a less key job in New York, or he’d keep them off the road for a month, then bring them back.”

By September the scare stories were pouring out of Rockefeller Plaza. Editors in tears, tape on the floor, engineers infuriated. But by then Ohlmeyer had learned who to come down on—and who not.

“I was depressed for the first six months,” Ohlmeyer says. “I used to wake up with the cold sweats. I didn’t know how I was ever going to do the Olympics. I knew more about TV than anybody there and they all seemed to be floating. Part of it, I was scared. So I screamed very loudly because you don’t have enough time in this business to cover for everybody’s mistakes, and I ended up embarrassing a lot of people. But now we look a whole lot better. I think we have the best graphics in the business. Besides,” he adds, “if I wanted to make friends I would have joined the YMCA.”

At 30 Rockefeller Plaza, they call him “The Big O,” but for all his tyranny, Ohlmeyer is a compelling character. At the extremes, women might adore him and men fear him, but nobody can ignore him. For the maniacal drive is tempered by a quick wit, an engaging smile, and more deadly still, a flair for the unexpected.

Midway through live coverage of a golf tournament, Jim Marcione, an associate director who stands behind Ohlmeyer with a stopwatch, erred in his time calculations and fouled up. He was afraid to admit the mistake. “So I made up some excuse and shifted the blame.” Ohlmeyer threw down his headset and jerked around. To Marcione’s amazement, Ohlmeyer was laughing. “Jim,” he said, “don’t ever try to bullshit the great bullshitter.”

About a year ago a company executive called then sports vice-president Scotty Connal and Ohlmeyer in for a lecture on cost-cutting. The executive said there was no reason to rent standard-sized cars when compacts would do, and what was wrong with the Holiday Inn? Connal agreed. “What do you think, Don?” asked the executive. “It’s fine with me,” Ohlmeyer replied. “As long as Scotty doesn’t park his compact next to my limo.”

While his critics inside and out of NBC will argue that Ohlmeyer’s style and methods have created some problems, no one can argue that he hasn’t done wonders for the network’s image and bottom line. Arledge’s assessment: “Don has succeeded in bringing NBC up to the technical level of the other networks. You have to catch up before you can lead. Whether he can take that next step, to be innovative, I don’t know.”

SportsWorld, the Sunday anthology show he started two years ago as an Olympic training ground for the production staff, may not be competitive with ABC’s Wide World of Sports, but it is neck and neck with Sports Spectacular on CBS. And it makes money. Olympic Moments, those 60- and 90-second spots sponsored by AT&T, was his idea. And it is said they have brought the network $6.5 million in two years.

But money isn’t everything—not even in television. Within the industry, NBC on-air talent is still ranked third. And Ohlmeyer hasn’t made a major effort to recruit the big names, with the exception of Don Criqui, who came from CBS. Ohlmeyer says he would rather develop the talent.

“When I came here Dick Enberg and Merlin Olsen [the No. 1 football team] were nowhere as polished as they are now. And Enberg and AI McGuire are the best basketball announcers in the business. I’ve left baseball alone. Don Criqui was wasted at CBS; now he’s a major personality. And Bryant Gumbel, who was second banana on the pregame show, has become one of our staples.”

Gumbel has improved but is still not held in the same regard as CBS’ Brent Musburger. And where are Ohlmeyer’s Howard Cosells, Jim McKays and Don Merediths?

“ABC,” Ohlmeyer says, “had 15 years to develop their talent.”

Predictably, he has left a lot of rumpled feelings in his wake, both personally and professionally. “He’s very immature in some ways,” says one NBC man. “He’s a genius in the tape room, but I’m not sure he’s as good a director as he thinks he is. In golf, he cuts all over the place. Sometimes I think he uses effects for the sake of effects.”

Ohlmeyer also has a reputation for being insensitive.

“I was doing football, basketball and Sports World,” associate director Marcione says. “I was working as hard as anybody. All-night edit sessions Saturday night and Sunday morning. On the air Sunday afternoon. Then he would walk into the room and not even say hello. Often he didn’t say ‘good job,’ except maybe as a generality to the whole group. A lot of time in the hall he didn’t say hello. I resented it and it made me incensed and it made me work harder.”

Says Ohlmeyer, “I know I can be abrasive. And I’d really like to be liked. That’s a big job and I’m under a lot of pressure. I get 80 phone calls a day and people are always banging on my door. Sometimes, if I don’t speak to people in halls, it’s because I honestly don’t see them.”

On a recent Friday, he flew from Los Angeles to Orlando to direct a golf tournament. An hour after he walked out of the control truck on Sunday, he was back in the air to L.A. to watch the final shooting of The Golden Moment (a story about an American decathloner who falls in love with a Russian gymnast at the Moscow Olympics). That was Monday. Monday night he caught the red-eye to New York. Wednesday afternoon he went to Alabama to tape a beer-drinking contest for the 90-minute pilot of his new anthology show, Sunday Games, which, he says, “is a show about the sports that real people play.” Which is also a comment on Ohlmeyer’s vision of sports’ future on TV. One segment features America’s toughest bouncers. To determine who was best, the bouncers had to throw people for distance and run through an obstacle course full of tables. Ohlmeyer says it’s “better than having my kids watch The Gong Show.”

Thursday night he was back in New York to coordinate NBC coverage of eight NCAA basketball games on Saturday. For six consecutive hours Ohlmeyer instructed the directors at each site, deciding when to switch from one game to another, when commercials should be slotted, what anchorman Bryant Gumbel should say during cutbacks to the studio—all the while watching the games for halftime highlights. Then he went to dinner. For four and a half hours he held court in a Mexican restaurant, talking non-stop TV.

Ohlmeyer’s theory, largely learned from Arledge, is simple: Show the play. Switch to a crowd shot. Get the audience involved.

“I tell the announcers, ‘Mention the quarterback is from Tuscaloosa. People from Alabama will take an interest.’ When Golden Richards catches a pass, throw up a freeze-frame of his face. He looks like a Greek god; that gives the women a reason to root.”

Another motivation is to keep people from being bored. In baseball, he uses a video compressor to squeeze a second picture onto the screen to show the ball and the baserunner simultaneously. In football, the cardinal rule at NBC is two graphics per play. With the TV talk, there’s hardly enough time for the tacos.

“He’s bored with people who don’t talk TV,” Muffy says.

Twelve hours later he oversaw eight more NCAA games, before he headed for L.A. In 10 days, he had traveled more than 15,000 miles.

Even in his spare time, Ohlmeyer is obsessed with TV. In the den of his Fifth Avenue apartment, there are three color TVs, all of which, Muffy testifies, are always on. At his office, or in front of company, he’ll be polite and turn the TV off; but then, the sounds take over. Ohlmeyer’s musical tastes run to the Asylum Choir, Willie Nelson, Linda Ronstadt and Jerry Jeff Walker. In two years, he has never taken a meal at the dining room table—dinner is served in the den.

Ohlmeyer did take time off when he married Muffy two years ago. “We were married on a Saturday,” Muffy says. “Don had been in Palm Springs directing the Bob Hope Desert Classic. The ceremony was at noon. We didn’t get on a plane to go back to Palm Springs until four. The other time he took a vacation, we were supposed to go to Hawaii for 10 days. He spent the first three on the phone to NBC. The fourth day he said, ‘Pack. We’re going.’ ”

Mason says, “I don’t really know what drives Don. I don’t know if it’s insecurity, or some compulsive drive or just plain insanity. But I know I have never met a man who has the physical and mental capacity to work as hard as Don does.”

“The truth is,” says Ohlmeyer, “I’d give it all up to be a rock ’n’ roll star.”

Some people see an Arledge complex hanging over Ohlmeyer. Chet Forte says, “He wants to show he can do the same things Roone does and do them better. That’s why he had to take on the Olympics. I don’t know if he needs to prove it to himself and ABC, but to people in the industry there will never be another Arledge.”

Ohlmeyer says he really isn’t sure what drives him. “I’ve never really thought of Roone as some kind of professional father figure. But maybe subconsciously I do. Maybe I have to show my father I can do it. But basically, I think I just have to prove to myself what I can do.”

The father figures it this way. “There was some jealously and resentment of Don at ABC,” Arledge says. “There was the feeling that he had a special relationship with me, which he did. But in this business you don’t get special treatment unless you’re awfully good.

“What impressed me most about Don was that he wouldn’t settle for anything that wasn’t as good as it could be. To be really good you have to pay attention to detail. You either see the little things that could be better or you don’t. Don does.”

But the man who has produced seven Olympics for ABC says, “The Olympics are the biggest test there is in TV. Everything Don’s done at NBC was geared towards Moscow.”

Privately, Ohlmeyer wonders if he is not like the American athletes, having trained hard for three years, only to have the spotlight killed before he had a chance to go on live.

There’s still a chance, of course. But it’s thin. Even if the American athletes end up going, NBC doesn’t think it would look good to buck the President. It’s a dicey situation. Ninety per cent of NBC’s $87 million rights money to Moscow is insured by a Lloyd’s of London policy. The policy will not be paid off if America sends a team.

But what if the boycott were suddenly, magically, called off? “We’d be ready,” says Ohlmeyer. “It might not be as good as we’d hoped, but we’d be ready.”

And what if the boycott sticks, how will you spend your summer? “I could make another movie. Or I could take some sane time.”

Pause.

“I’ll probably make the movie.”

[Photo Credit: Zoe Leonard The Art Institute of Chicago]