The old man was hurt at Pearl Harbor and moved to Florida to mend after they processed him out of the service. He’s been there, and in his wheelchair, ever since. Forty-two years. He lives in Miramar now, just across the line in Broward County, and drives down every morning when the Miami Dolphins practice.

It’s ten-thirty in the morning, the first Monday in May, the first day of spring practice. “This place keeps me alive,” he says. He moves the chair down the sidewalk, pulling himself along with his feet. The sidewalk ends a few yards from the field, and he pushes with his hands to get over a bump at the gate and then finds a place on the forty-yard line to watch. Out on the field, sixty or seventy football players are lying on their back, one leg bent under them and flattened sideways, the other one straight out in front. If you found somebody that way on the street in the city there’d be six winos standing over the body, all telling each other not to move him.

On signal, the players all lean forward and press their faces into their outstretched knee. Then they reverse the legs and press their faces into the other knee.

While the players stretch, six or seven men in sun visors and ventilated shirts walk among them, frowning and smiling, saying, “Stretch it out, Bob,” or “Stretch it out, Jim.” Coaches.

Nobody knows, of course, why coaches smile when they smile, or even what it means when they smile. Breaking something you don’t need to play football will do it—a nose, for instance. Remembering a broken nose will do it too. As a rule, terrible weather will do it, but a great catch won’t. A great tackle sometimes will, especially if the tackier can’t quite put his finger on who he is afterward. You don’t have to know where you were born to play football; you find out what you are as you do it.

It’s a rule of nature: Lost is lost, girls or talent. Girls are the harder rule, as a matter of fact, because in a way coaches do get back in touch with their talent, or at least forget that it’s gone.

For a long time I used to think coaches smiled because something had reminded them of the old days, when they made tackles and forgot who they were, or broke noses of their own. I thought somehow it must have been more fun in the old days, and that coaches were tougher than the people who came along after them.

Sometimes that happens to be true; mostly it isn’t. Most coaches, it turns out, were mediocre college players, if they played in college at all. A lot of them lost their taste for hitting after they got out of high school and found themselves on a field where everybody could hit back. And for a lot of them, their senior year in high school was as good as it ever got, the only real shot at fame and pussy they ever had. They had coaches then who told them it would last forever, and advised them to put off the girls till later. The ones who believed that became coaches themselves.

As a group, nobody has missed out on more pussy than football coaches. Hell, yes, they smile at funny times. And once it’s gone, it’s gone. Even if you went and found the girl, and she wasn’t divorced twice and smarter than you, and smiling while you talked like you were the 106th one she’d met this week—even if she’d bring her old cheerleading uniform to your hotel room, you still might as well try to unboil eggs.

It’s a rule of nature: Lost is lost, girls or talent. Girls are the harder rule, as a matter of fact, because in a way coaches do get back in touch with their talent, or at least forget that it’s gone.

They go back to high school, where they were comfortable. They inherit a world built on rules and a vocabulary borrowed from coaches before them, and if they set things up right, and they know who to be nice to, they can stay famous forever.

Of course, the coaches walking among the players now didn’t go back to high school to get comfortable. Most of them played football in the National Football League, including the man himself. You don’t have to know anything about football to see who that is. He is smaller than the players, a little heavy in front and back; everybody on the field keeps track of him, and he sees everything that goes on.

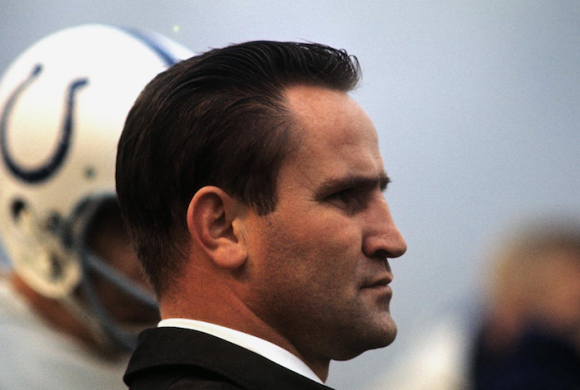

His name is Don Shula, and he is the most successful football coach who ever lived. He was not the most successful player who ever lived, but he stayed seven years in the league as a defensive back—at Cleveland, Baltimore, and Washington—in the best company there was without any kind of talent that you’d notice, unless you count brains.

Shula is limping today, bone spurs in his heels. He and another coach, named John Sandusky, meet over the twisted body of the third-string quarterback who may be in a losing fight to stay on the team. The coaches put their hands in their hip pockets and bend into each other to talk, studying the grass. Sandusky is tight-skinned and huge and packed like the webbed bags of Florida oranges you buy out on the turnpike. He limps on high right leg, and when he jogs from one place on the field to another, you can see how it hurts him to move. Sandusky played tackle both ways, offense and defense, for the Cleveland Browns back in the Fifties.

He is a little heavy in front and back; everybody on the field keeps track of him, and he sees everything that goes on.

A few yards away, running-back coach Carl Taseff is favoring a left leg that comes in to his body at the same angle as the last prong on a fork. Tree roots grow straighten Taseff played in the same backfield with Shula at John Carroll University in Cleveland, and played with him on the Browns, and then at Baltimore.

In all, there are five or six coaches on the field—including Shula’s twenty-four-year-old son, David—who played in the NFL, none of them sideways field-goal kickers or backup quarterbacks. They were all part of the collision of the sport, where the winning and losing is.

Football, of course, depends on collision for its sound, and sound for its personality. There are full-tilt collisions in the open field that you can hear all the way up in the 800 seats, and softer-sounding collisions all up and down the line of scrimmage every play. The linemen tend to growl, though, and when they come together—even though it’s only with a yard or two to gather speed—you can hear what goes on inside a human body in that moment when everything stops.

More than anything else, it sounds uncomfortable, which is a lot of what football is about. Uncomfortable. The good players numb themselves to it all, the collisions and the damages. Sprained fingers, broken toes, bruised ribs, jammed necks. I’m not talking about torn knees or broken legs, which nobody ignores, but the smaller problems—in football they call them nagging injuries—that you spray with ethyl chloride or you shoot with Novocain and then tape up. If someone has stepped on your toe and broken it, you tape it to the nearest toe that isn’t broken. It’s the same way with fingers and with bruised ribs. Ankles and feet are taped even before they get stepped on. There isn’t much that can go wrong with you on a football field, when you come right down to it, that somebody isn’t going to try to tape up so you can play some more.

That was truer in the Forties and Fifties, when Shula and John Sandusky and Carl Taseff played, than it is now, and watching them on the field, you think of all the taping that went on in all those years. You wonder if one day when it was over they unwrapped themselves and found out they didn’t walk like regular people anymore.

The old man in the wheelchair looks out over the field and smiles. “I got to go into the hospital this weekend,” he says.

I ask for how long. “Who knows?” he says. “Maybe a couple of days, maybe a long time.” He shrugs. “I got to do it about twice a year, get everything cleaned out.” He looks down at himself and the wheelchair. He says, “You know what I mean.”

Shula keeps the players on the field an hour and a half. The draft has just been finished, and Miami has taken a kid from Pittsburgh in the first round, a quarterback, and when he throws the ball, it seems to come off his fingers almost by itself. Shula watches the new quarterback leave the field, and all the others. He is coming near the gate himself as the old man, following the last player out, catches the wheelchair at the bump and for a moment pushes against it without moving.

It would be an easy thing to push him through, but Shula turns around instead to let him do it himself. “These are the best fields anybody has,” he says. And when he turns back, the old man has rocked himself over the bump, without help, and is back on the sidewalk.

The practice has been shorter than usual, and Shula decides to run before lunch. He heads out on heavy legs, out past the fields to the scrub pines, and comes back from the. other direction half an hour later, his ventilated shirt soaked through with sweat and sticking to his stomach. “I was on the scale the other day,” he says; “almost two-twenty.” He looks at his stomach as he says that, a happy, penguin stomach. “I don’t try to break any records running, I just like to keep everything working. This thing with Van Brocklin is a little scary.”

Early that morning, Norm Van Brocklin had died. Van Brocklin was among the best quarterbacks ever to play football. Afterward, for thirteen seasons at Minnesota and Atlanta, he was also among the game’s most innovative coaches. As a player for the Los Angeles Rams, he once picked up a Ram owner by the ears and asked to be traded. As a coach, he was asked on live television if the game his team was about to play was special because his old enemy Fran Tarkenton was the opposing quarterback. He said, “What kind of a chickenshit question is that?”

Except for one year at Atlanta, the teams Van Brocklin coached never won much, and he died on a pecan orchard in a place called Social Circle, Georgia, still trying to get back into the game. A heart attack. Shula had tried to help him when nobody else in the game would answer Van Brocklin’s calls. “The last time I called him to play golf,” Shula says, “he asked if the course had carts. I said, ‘What for?’ and he said he couldn’t walk eighteen holes anymore. I said, ‘You’re kidding,’ but he wasn’t.”

The feeling comes into Shula’s voice all over again when he says “You’re kidding.” He can still see Van Brocklin on a football field running the Los Angeles Rams; maybe he sees himself and John Sandusky on the other side, trying to keep him out of the end zone.

“Norman never found the middle ground,” Shula says. “With him, it was always all or nothing. He was all the way up or all the way down; everybody was for him or everybody was against him. He never got that perspective you need to last from week to week.”

Perspective comes hard in football. On one hand, it’s a game, and its consequences don’t extend beyond the people who care about it. On the other hand, it’s a world in itself, designed in a way that condenses most of the things you hate to see coming in this life into a very short period of time: decision, pain, fear, embarrassment, confrontation, spit hanging from the bars of your face mask. The rewards for putting up with that are real too, beyond the money. A professional football player may have to find out who he is more times on a single Sunday afternoon than most of us do in a year, but when he is successful, he is reminded of it. He goes up and down by the play, by the game, by the season. And if there’s any question about it, there is always a camera going somewhere, recording everything he does.

Shula watches the films relentlessly, every morning, grading every player on every play. “I never get tired of watching films,” he says.

And if the players live in an up-and-down world, the coaches are even more vulnerable. After all, it’s their image the world is created in. They stand on the sidelines, without the distraction of physical exhaustion, and are somehow responsible for everything going on.

“It hurts when you’ve got to let go of a player who’s been around a while,” Shula says. “I had to sit across from Jake Scott when we traded him and tell him he didn’t fit in here anymore, thinking about all the things he’d done for me, the ups and downs we’d been through together.” Scott was a safety and kick returner on Shula’s world championship teams of 1972 and 1973.

“If a kid comes in without the tools, I’ll tell him he doesn’t have them, or that he doesn’t fit in here but he might fit in somewhere else. That doesn’t bother me; in the long run it helps him. But the guys who’ve been through it with me, who’ve done what I asked…”

He leaves it there.

“You feel like you used them?”

“No,” he says, “not used. In football, you have to get it done. No matter what you say you can do, pretty soon you have to prove you belong here, you have to line up and hit and run and think. You find out what people are made of.

“It’s more black and white than on the outside, but as you get older you see the grays too. Van Brocklin never made any accommodations. He never got used to the grays.”

Shula showers and puts on a fresh ventilated shirt, then heads over to the Biscayne College cafeteria for lunch. The Dolphins have been at Biscayne College—a small Catholic school in the northwest part of Miami—since 1970. Shula likes the grass. He bought a house close by, in Miami Lakes, and his wife helped raise money for the school library (“Dorothy stepped in there and did a great job”). So when one player called the training facility Cockroach City and expressed misgivings about Miami—“I’m not used to New Yorkers, or tourists, or Cubans”—Shula called him up that day and brought him into his office to talk.

Nobody wants to get called into Shula’s office.

All Shula has on his plate is a one lonesome hamburger. “There are rumors he eats,” a writer said, “but nobody’s ever seen it.”

One of the writers who covers the Dolphins remembers talking about that with Ed Newman, an eleven-year offensive guard who can bench-press something over five hundred pounds and is one of the strongest players in football. “He was sitting in front of his locker, this huge, strong man, quaking at the thought of having to go in the office and talk to Shula. He said, ‘You guys come into the locker room right after the game, which isn’t really the best time because we’re still emotional, and maybe somebody says something a little bit wrong, and the next day it’s in the paper, and then we got to go in there and sit in the hot seat.’ He nodded toward Shula’s door when he said that, but he wouldn’t look right at it. Quaking.”

The writer stopped and shook his head. “This might be the hardest football team to cover in the league,” he said, “and the reason is, everybody’s afraid of Shula.”

“Why?” I said.

“You’ve never seen him mad,” he said. “His face changes. I mean, it doesn’t look like the same person—it doesn’t look like a person at all. It looks like a gargoyle, and when he gets like that he’s merciless.”

“How often does that happen?” I said.

The writer said, “Haven’t you asked him anything stupid?”

I went over the highlights of our conversations.

I’d said, “Uh, did you ever have a job?”

He’d smiled. “Well, just football….”

I’d said, “Do you have to be smart to be a professional football coach?”

He’d said, “Not too smart.”

I’d said, “Well, if we traded jobs, you wrote this and I coached the Dolphins this year, who would screw up worse?”

He’d said, “Well, there’s a lot of X’s and O’s to learn.”

“Everything considered,” I said to the writer, “he’s been real pleasant.”

“He’s on his good behavior,” the writer said. “After every game, the regulars just wait for somebody to ask something stupid. You know it’s going to happen, then it does, and Shula jumps all over them. You’ve got to admit, though, there’s a sense of fairness to it. Shula can be a bully, but he won’t pick on somebody helpless. A radio station sends a new kid or some girl over to cover the game, he isn’t going to shout at them. He only does that if you ought to know better.”

“Does anybody ever shout back?” “No,” he said, “not shout. Joe Robbie [who owns the Dolphins] shouted at him one year at the annual awards banquet, came in front of a hundred people and started yelling.”

“How did Shula handle that?” I said. It says something to me when a let’s-all-die-together-on-Sunday football coach comes on television after a play-off win and thanks the owner—he will call him “mister”—before he says anything about the players.

The writer shrugged. “He yelled back. He said, ‘If you ever shout at me again, I’ll knock you on your ass.’”

One section of the Biscayne College cafeteria is blocked off for the Dolphins, and one table of that section is reserved for the coaches. That table is near the door. The reporters have a table a few yards away, and the players sit at tables in the back, as far away from trouble as they can get.

Shula takes several minutes going through the cafeteria line, looking everything over, but when he comes back to the table, all he has on his plate is one lonesome hamburger patty and a spoon. He looks at the plate, unhappy, and before long you begin to feel sorry for it. You wish he’d stare someplace else.

“There are rumors he eats,” another writer told me, “but nobody’s ever seen it. On the night of the draft, though, a guy delivered four huge pizzas to Shula’s office. I guess there were maybe four coaches in there with him, but these were giant pizzas, and two hours later, when they let us in, all that was left was the crumbs.”

Shula finishes lunch in half a minute and heads back to his office. Maybe there is a piece of pizza someplace under the papers on his desk. Besides the desk, the office has ten or twelve chairs, a blackboard with magnetic dots and darts to diagram football plays, a depth chart. A depth chart ranks the players at each position and indicates, in the end, who can stay on and play, and who has to leave. On the chart, Jim Jensen—the third-string quarterback who may be losing his job—is still the third quarterback, but the rookie doesn’t have a tag with his name on it yet.

Shula settles into his chair. There are trophies all over, some with gold footballs, some with little dolphins in football helmets. There are proclamations of love and gratitude from people who don’t know him, and there are portraits of Shula. Two in the office, one in the hall. None of them are well drawn, and they’re all from younger times, but they’ve all got the character right.

I have never seen a statue that wouldn’t look better with Shula’s head on it.

He looks at something on the desk; I ask about Joe Robbie. “I respect him,” he says, and then he talks about the money Robbie has made and the franchise that the money has built.

I put it a different way. “How do you get along with him?”

“I don’t see him that much,” he says. “Most of the things I need, I deal with his son Mike. If I need Joe, I pick up the phone and call him, but it doesn’t come up much.”

Nobody who has followed Shula’s career—the thirteen years at Miami, the seven in Baltimore before that—can question that he finds things in people.

I put it a different way. “I understand that after the Dolphins went to the Super Bowl last year Joe Robbie didn’t want to give any of the bonus money to the guys who carry the balls and equipment, and that you took money out of your own pocket and collected some from the other coaches so they’d get something.”

Shula is a long time answering. “You’re getting me in hot water here,” he says. “I can’t tell you what to do, but I can promise you Joe Robbie is going to be upset to see that in print.” And that’s as much as he is going to say about what he did. He won’t ask me to keep it out of the story, although that’s clearly what he’d like, and he won’t tell the simple lie that would get that done. Shula works for Robbie, but he doesn’t belong to him.

I look at the depth chart again and ask about Jim Jensen, who’d had a bad practice that morning. Besides being a third-string quarterback, Jensen played special teams last year, throwing himself full-tilt into tackles and linebackers time after time. He’s done everything but grow tits and pompons to stay around, but the rookie from Pittsburgh has something he wasn’t given, and he is afraid there won’t be room for him now.

“I already had a talk with him,” Shula said. “I wanted him to see it was all to his advantage to give it his best shot. That way, if he can’t stay on here, somebody else may pick him up. I want my players to know I’m human too, that I’ve been through it and I know what it’s like. I can put myself in a kid’s shoes. When I was younger—back when I was at Baltimore—I didn’t think about that much. But I’ve got kids of my own the same age as some of these players. Yeah, they’re men, but they’re kids too.”

I ask how that balances with the fact that players are afraid of him. “Well,” he says, “some of that’s good too. There’s players you’ve got to keep on and there’s players you’ve got to leave alone.”

Nobody who has followed Shula’s career—the thirteen years at Miami, the seven in Baltimore before that—can question that he finds things in people. If there is a single quality that separates him from the others, it’s that. He just knows where to look. His teams always have important players who wouldn’t be important anywhere else. Larry Csonka, the all-pro fullback, was like that. On this team it’s the Blackwood brothers, Lyle and Glenn. They are one of the best pairs of safeties in football, only because Shula put them in the same defensive backfield.

And it was Shula who gave the ever-colorful Thomas “Hollywood” Henderson a tryout after he had been dropped by Dallas, San Francisco, and Houston and nobody else in the league would even talk to him. “I’m not afraid to take a shot with a guy,” Shula says. “Hollywood could have been a productive player. He came in and worked hard. I figured we’d work with him as long as he’d work with us, and he was getting it done. I think he would have played for this team if he hadn’t broken his neck. It happened in practice, and I went over and talked to him later and told him I was sorry, that I thought it was working out.”

I think about some of the other coaches in the National Football League—Frank Kush at Baltimore, Tom Landry at Dallas, half a dozen others—who try to assign one personality to all their players. Shula understands things better. He knows even a small world is too complicated for the creator to keep track of sinful thoughts.

I am suddenly reminded of another coach and another broken neck. The neck belonged to a linebacker, a vicious hitter who played wearing a neck brace. A friend was sitting with the coach after a game, admiring the linebacker’s tackling. The coach said, “Yeah, and he’s playing with a broken neck.”

The coach’s friend couldn’t believe it. “What guts,” he said.

The coach shrugged. “He doesn’t know,” he said.

Shula understands things better. He’s got to live in the world he’s built. He won’t lie to his players; he won’t let personal feelings get in the way of who goes and who stays. “To be here,” he says, “physically you have to be trying as hard as you can, every play. I can’t do business with anybody who won’t do that. But liking somebody personally, no, that’s got nothing to do with it. I’ve had players I didn’t like who could get it done on the field…. Yeah, I tell them I don’t like them. I’m not much of a con man, and they know if you’re trying to be somebody you aren’t anyway. The ones that bother you are the ones you do like who don’t belong here anymore.”

Among the players that no longer belong are Randy Crowder, Don Reese, and Mercury Morris, all of whom were convicted in the last several years on drug charges. Some coaches—most of them, I think—would have taken that personally, but there is nothing angry in Shula’s voice when he talks about them. “I don’t have total control over my players,” he says. “I wouldn’t want it. We work hard on the field and hard in the classroom, and there isn’t a lot of time for the other. I judge people on what they do here, and if they’re good enough to stay, I assume things aren’t happening on the outside. I’m an optimist. If I find out something different, I’m disappointed. But it’s not disappointed for me, it’s for them.”

Shula was born in Grand River, Ohio, in 1930, one of six children. There had been another one, an older sister who died of a head injury after she fell off a tricycle. His parents were Hungarian and Catholic, and Shula still goes to mass every morning on the way to work. “It’s a private thing,” he says. “I don’t try to convert anybody. Tom Landry does that over in Dallas, he’s a reborn Christian I guess, but I just go to show I’ll do something extra. It’s a sign of respect, that I’m not a gimme/help-me kind of guy. I’ve been blessed, and I’m trying to give something back.

“My father was one of those guys who just worked all his life. He was a nurseryman, that was the kind of work he loved, but after I was born there were triplets, and he couldn’t make it on sixteen or eighteen dollars a week. He took a job as a commercial fisherman on Lake Erie, and after that we moved to Painesville, where he went to work as a tinner in a factory.”

I remember a bronze plaque hanging on the wall outside Shula’s office with a long quotation that begins, “I’m just a guy who rolls up his sleeves and goes to work.” I’d wondered about that, because people who just roll up their sleeves and go to work don’t write it in bronze and hang it on the wall.

“My dad was never an athlete. He had good coordination, but there was never any time. He worked all his life, and one of the things that makes me happiest now is that before he died I got to take them back over to the old country.

“We went to Budapest, and then we drove about a hundred miles and found the little town he was from and looked up all the relatives. And then we went to Rome and while we were there the pope came out. That was everything he wanted.”

Friday-afternoon practice begins with the sun hot enough to blister the tires on the old man’s wheelchair. He is back on the forty-yard line; a maze of soft black bugs are mating in the air around his feet. The bugs have been having their own minicamp all week long, mating and staining your skin when you slap them off. For some reason nobody can figure out, they don’t mate on Shula.

“Did you know David Woodley invited me to his wedding?” the old man says. “I was the only one he invited.”

Woodley is the Dolphins’ starting quarterback, and after stretching exercises he and Jim Jensen and the rookie from Pittsburgh take turns throwing passes to the wide receivers and running backs. The defensive team tries to bat the passes down.

Shula stands behind the quarterbacks, watching everything on the field. “That kid,” he says, nodding at a small, first-year defensive back, “came in here with a thirty-eight-inch vertical jump, can run a forty [yard dash] in four-three. He’s going to make it interesting for somebody before it’s over.” There is some pleasure in that, but it is one of the rules of this place that nobody makes it interesting for the coach. A coach can get fired, of course—although Shula probably couldn’t—but no coach has to go to practice and watch somebody take his job away.

While Shula talks, the quarterbacks line up their backs and receivers and throw their passes. Jim Jensen isn’t throwing any better than he was at the beginning of the week, and when he dumps a seven-yard pass over the head of one of his receivers, Shula claps his hands and shouts, “C’mon, Jim, we’ve got to hit that pass.”

Jensen closes his eyes and slaps the side of his helmet, which he is wearing. The rookie from Pittsburgh is up next. He takes the ball from center, drops back six quick steps, reading the defense, and then his arm moves—as easy as pointing directions out to the Palmetto Expressway—and heads the ball off into the sky, into the afternoon sun, and it hangs up there a moment, almost as if the wind had blown it, and then it drops, as random as talent itself, somehow forty yards downfield, between defensive backs, somehow into the hands of a wide receiver.

There are a few whistles, some clapping, somebody shouting, “Good touch, good touch.” The rookie from Pittsburgh is smiling when he comes back to the spot next to Shula. Shula looks straight ahead, arms folded, frowning his happiest frown.

And Jim Jensen, who threw his narrow body into tackles and linebackers last year to stay in the game, stands by himself looking at the grass and the soft black bugs, and somewhere inside he knows it isn’t enough. That before long he won’t have anything to trade to stay here.

You wonder where he will go. You wonder where they all go.

Out on the field there are seventy football players, every one of them blessed. The blessing is their talent, and they accept it—as much a part of them as their ears—until one day when, for no better reason than it had in coming, it goes away. A few of them may find something to replace it; most won’t. The colors are paler on the outside. You think again of Van Brocklin, dying on a pecan orchard in Social Circle, Georgia.

Some will become coaches. Middle-aged men with zippered knees and spliced tendons that hurt from the minute they get out of bed in the morning. There are eight of them on the field now, beyond them one old man in a wheelchair, and beyond him the scrub pines and fences that are the boundaries of this place.

Don Shula stands at the center of it, arms folded, frowning, judging who can stay. He sees everything here, he records it all in his mind and keeps it all on film to make sure. He doesn’t play favorites or tell lies or make apologies. His world is on the up and up. That’s how he set it up, and, as worlds go, you’ve got to admit it works better than Miami.

The players come and go; the talent stays. Talent is hope, and Don Shula stays with it.

[Photo Credit: Neil Leifer/SI]