Eddie Murphy, a man of 21 years, has a check for $45,000 in his back pocket, a manager with tinted sunglasses standing near the bar, a producer from a Hollywood studio watching him from the door, a sound-and-video crew recording his every word, a full house chanting his name over and over again, a real-estate tycoon spotting him as an investment, a clean sweater and blue jeans covering his long, thin body, a gold watch on his dark wrist, a mother and a stepfather sitting close at a reserved table, a Datsun 280-ZX double parked on Second Avenue, calling him to fly (its dark, shiny shell gorgeous in the lit frenzy of an Upper East Side New York May night). Eddie Murphy stands onstage at a comedy club and smiles, showing his puppy-white teeth. He grabs the mike hard.

“What are you laughing for?” he says. “You’re going to be leaving here in an hour saying, ‘The motherfucker wasn’t even funny.’” At the word motherfucker, the audience explodes.

Eddie Murphy’s manager laughs. His producer laughs. The real-estate tycoon laughs. His mother and stepfather laugh. “Ed-dee! Ed-dee!” says the crowd.

The comedian’s manager stands in the corner. His wife stands near him. He wipes a drop of sweat from his nose. A beat after the audience, he laughs in a syncopated rasp: “Ha-ha! Ha-ha!”

“I’m not here to talk about Ronald Reagan or politics or give you a message,” Eddie Murphy says. “Nobody’s going to spend their money to come out here on a Saturday night to hear a nigger complain about Ronald Reagan.

“I’m here,” he says, “to talk about my real comedy, which is about dicks, farts and boogies.”

Eddie Murphy, a kind of innocent, works a comedy club as though it were social-studies class between periods.

The audience goes berserk. Manager, producer, tycoon, mother and stepfather all seem to love that sound—they laugh and clap. But Eddie hardly notices; Eddie Murphy is working. “Dicks, farts and boogies,” he says.

Eddie Murphy, a kind of innocent, works a comedy club as though it were social studies class between periods. His strength and his momentum don’t have much to do with an early generation of club comics who won their professionalism on other people’s terms, trying to gauge what club owners and TV producers wanted. Eddie Murphy found his support at Roosevelt Junior-Senior High School, from his peers, the kids—and he took their fully developed endorsement as his security, as his merchandise, to the open market. He was seen; he was bid upon; he became a viable commodity.

He had a smooth and self-endowed power. He seized his audience directly and knew that tentativeness was counterproductive for him. He had learned from Richard Pryor that he was allowed to plug his huge voltage into a crowd and that they would sit up. He said shit and fuck a great deal (almost every other word, you felt), because he knew that it was like giving a high five to the audience and that black audiences liked it and white audiences were grateful for it. He was good with the girls in his class—he knew what would keep them entranced and what would turn them away—and he was good with the boys, whom he knew how to rank out. Eddie Murphy had his act down, because he was at that essential moment at the end of his adolescence when he was working on eight cylinders with no distractions, when honesty pays and existential problems lay low, when insight is yours and if they don’t like it, they’re wrong. Eddie Murphy was having his dandelion time.

“This was a good year for me,” he says to the crowd, “and not just because of the TV and all that shit, but I was happy and shit. Was it a good year for you? It was a good year for me. But some bad shit happened in 1981. They shot Reagan….”

Somebody in the audience claps and yells.

“Who out there clapped?” Eddie says. “You must be crazy. Shooting people, that’s bad shit; I don’t care who it is. I mean, that’s bad shit. They shot Reagan and they shot Sadat and Lennon and they shot the Pope. I mean, who would shoot the Pope? What’s your intention in shooting the Pope unless you’re saying, ‘Look, I want to get to hell and I don’t want to stand on line’?”

This hits the audience right, and they erupt.

“I mean, whoever shot the Pope, they’ll say to him, ‘You shot the Pope? Go on the express line, motherfucker.’”

The crowd goes mad for this, and Eddie no longer has to throw hard: He talks about getting hit by a car and about how he loves to take down any girl in sight (“When I walk into my room, the fish stop swimming”) and about how he suddenly has to deal with recognition on the street. His material is good, but his delivery sets up a hot and intimate relationship with his audience, so that even when he talks and riffs and his material collapses or just ceases to exist, he is still in there with them, hooked on the same intravenous line to childhood experience and neighborhood anarchy—the best friend, remembering the horror/ecstasy of growing up in an assaultive world.

Eddie is in the best position in which a young actor can find himself: Like Mae West and Lassie before him, he has the chance to walk into somebody else’s picture and walk away with it.

He tells a long and painful story about his father’s coming home drunk and challenging him and his brother to a fight. It is the best and the funniest piece of evocative sketch Eddie has. The gist of the story has to do with the boys’ bewilderment and irritation at seeing their drunken father infuriated by their manful, staked-out presence in his house. The father comes in blotto and they are watching Quincy, and there’s dog shit on the floor and he pushes them to a fight, putting his pay check down as the stakes. Eddie’s punch line is “We beat the shit out of him.”

It is a hard and self-revelatory piece of stand-up, pulled off with a guileless respect for the truth. It is the best thing he has, and he works more and more strongly as it goes along. It’s dangerous territory—while he negotiates it, he’s like a wildly intent sword fighter on a rocking ship’s deck—but it hits home and cuts into the audience. It’s experience raised to a new perspective, and Eddie has seen it, his own conflict, for a group of people who are no longer strangers. They applaud the sketch hard. Eddie grins and laughs an octave higher than usual.

He works on, and the real-estate tycoon—Sam Lefrak, owner of the vast sprawl of apartments known as Lefrak City, of tremendous New York tracts and of the record label for which Eddie will record his first album—gets up to walk out of the club. Eddie introduces him to cursory applause and does what the sure and the powerful do: He ranks him out before the Saturday-night crowd, certain that he can keep the whip of his jokes in control and away from Lefrak’s nose. Lefrak, looking as expansive as his ownings, stands in the middle of the floor at The Comic Strip on 81st Street and Second Avenue and watches the thin black kid, of whom he owns one of the early pieces, standing onstage grinning down at him. Lefrak is as happy as a Polaroid stockholder who has just been shown his first SX-70. He smiles, calls a quiet rejoinder to Eddie up onstage, gives a thumbs up and leaves. Eddie’s manager, the owner of the club, heaves a huge sigh and shakes his head back and forth. Eddie’s mother takes a long drag of a cigarette. The audience has turned back to the stage. Eddie Murphy has something to say about Chinese restaurants.

After the first show, Eddie, his manager, his mother and stepfather and his best friend, Clinton Smith, all go next door for a seafood dinner. They meet one of Eddie’s idols there: his fifth-grade teacher, who has come to take in the midnight performance. The entire night at The Comic Strip is being recorded for Eddie’s first album, and there’s an almost historic air to the evening. Eddie has been signed, as well, to act in his first movie. The Hollywood producer Larry Gordon has put him in a prison picture, a drama set for Christmas release, called 48 HRS. Nick Nolte is the star. Eddie is in the best position in which a young actor can find himself: Like Mae West and Lassie before him, he has the chance to walk into somebody else’s picture and walk away with it. The movie has surely been built that way—the producer very much wants Eddie Murphy to be a star, a big star.

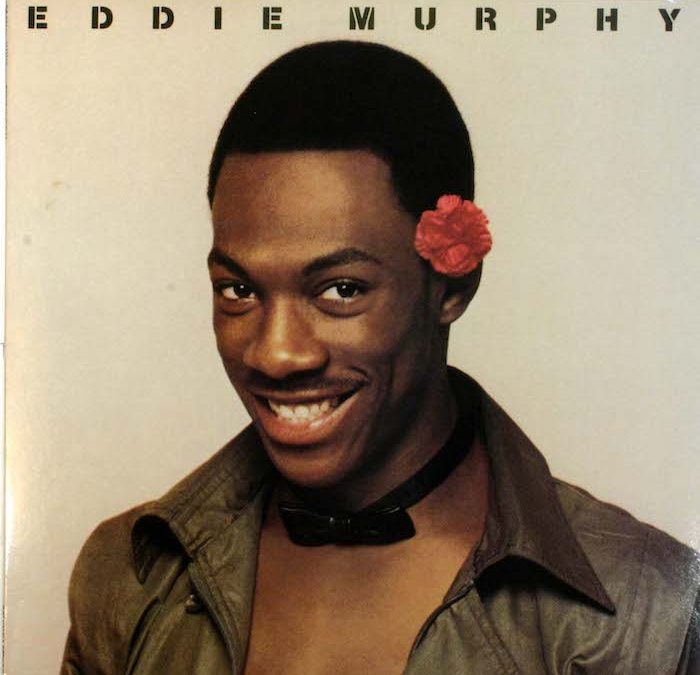

Eddie’s manager is exultant. The album, Eddie Murphy, is to come out in the summer. Eddie has the first advance check from it in his wallet. He could pay cash and buy a house or three or four good cars or 100 suits. He’s not thinking about any of that. He’s thinking about business, about cuts for the album.

“How’d it go?” he wants to know.

“Great, Eddie,” each person at the table tells him.

He looks at the table. He stares and nods. “I think I’ve got enough now,” he says. “I’ve got all I need. Next show, I can just fool around.”

Nobody disagrees.

Eddie walks back outside, onto the street, and looks over at his sleek Datsun double parked in front of the club.

“Nobody’s going to steal that?” he asks.

“Nobody’s going to steal it,” his manager says.

“Nobody’s going to tow it?”

“Not here,” says his manager.

“Hey, Eddie!” a white kid on the street yells. “Do Buckwheat!”

Eddie keeps walking. “Damn. ‘Do Buckwheat,’” he says. “‘Do Buckwheat.’”

“What’s the matter with ‘Do Buckwheat’?” his manager asks.

“Nothing,” says Eddie. “I just want to do better stuff than that.”

“Buckwheat!” the kid yells.

Eddie goes in for the midnight show, and the sound of stamping and yelling pants out onto Second Avenue. He passes through the crowd and the panting on the street gets louder and louder, until the club doors close and a boy with a big box radio walks by and two kids holding beer bottles push a full wire garbage can into the street and begin rolling it down the cobblestoned avenue.

When television was just getting going in the late Forties and the technology was massive and heavy—not tiny and full of chips—NBC filled Studio 8-H in the RCA building with election crews and concerts; ramshackle brilliance and highbrow shadows; Kukla, Fran and Toscanini. With its hanging-vine cables and concrete expanse, 8-H still looks like what television meant in the first place. The old-pro technicians wheel around huge booms, bringing up and bringing down the cameramen who swoop in the electric ocular and transmit images to the masses. Actors walk around wondering whether or not the producer likes them. The director blocks and choreographs. The producer, a young man in tight pants and a turtleneck, paces and whispers and looks very important. Two comedians stand on a low stage and look up at a disembodied voice.

“Joe, Tony!” the voice says.

Joe and Tony look toward the voice.

“Move together.”

They do.

“Step forward.”

They do.

“OK. Let’s go.”

Joe Piscopo and Tony Rosato, two members of a recent cast of Saturday Night Live, begin reading a mildly unfunny sketch about the show-business delusions of Pope John Paul II. In the sketch, the Pope, played by Piscopo, turns slowly into a Frank Sinatra paradigm of nasty egotism and disdainful cool as he receives more and more mass adulation. He develops a Las Vegas harshness. He visits Africa.

“Ed-dee!” the disembodied voice calls. “Where the hell is Eddie?”

Eddie Murphy looks up out of the shadows just beneath the stage. He blinks his big eyes a couple of times. He doesn’t move. This sketch he’s been watching has nothing to it.

“Where the hell is Eddie?” says the voice.

“Here I am,” says Eddie Murphy.

“Well, get up there,” the voice says, “You have a scene.”

Eddie Murphy blinks a couple of more times. He is to play an African priest in the sketch, one of the few filler parts he has had to kick in to the show in the months since he has become its most distinctive personality. Not only that, the sketch has a gratuitous race joke in it, the only point of which is to get a laugh out of Eddie’s black skin.

“I’m coming,” he says and hops onto the stage.

“All right,” says the voice, “now open the door and say your lines, Eddie.”

He walks through the sketch, reads his lines, finishes and hops off the stage and leans against an empty throne to be used in another sketch. He looks off at nothing in particular, his 21-year-old-boy’s face calm, without a crease in it. He listens to the lines being read onstage, puts his hands on the arms of the throne and shakes his head.

“Mediocre stuff,” he says. “Really mediocre stuff.” Eddie Murphy shakes his head another time, almost wearily, runs his hand over his smooth face and walks back to his dressing room to call Clinton Smith.

“This kid,” says Eddie’s manager, Bob Wachs, “this kid has instincts like you cannot believe. Like you won’t believe. Like you will never believe. This kid has instincts.”

Wachs is standing in the elevator lobby of International Creative Management, a huge talent agency that handles many important entertainers. I.C.M. takes up offices on several floors in a skyscraper on 57th Street in Manhattan. Eddie is to meet Wachs there to discuss his future in the movies, but he has not yet shown up.

“He’ll be here,” says Wachs. “This kid, you will not believe what instincts he has. Last week, we were out in Hollywood, you know, seeing some movie executives—and they were diddling us around, you know, offering us the moon but no money. And Eddie is sitting there being told by a bunch of movie executives that he is the greatest thing to come along in who knows how long a time—since forever. Now, this would turn some people’s heads, you know, but not Eddie. Eddie says to me, ‘If they’re not going to offer us a deal, let’s go.’ They didn’t, and we went. What dopes.

“I’ll tell you, though: As we were walking out from one meeting, Eddie turned to me. ‘I’ve always idolized Richard Pryor,’ he says, ‘but the way they’re talking, I’m not going to be Richard Pryor; I’m going to be bigger than Richard Pryor. I’m going to be Charlie Chaplin.’

“That,” Wachs says, “is how they were talking.”

He takes off his tinted sunglasses. He is a handsome man, around 40, with large, open features and a slight resemblance to George Segal. “Now, I don’t know if we’re going to be that big—but we’re going to be big.” He looks through the revolving doors and Eddie is not in sight. “The way they’re talking, anyhow,” Wachs says.

Wachs met Eddie Murphy a couple of years ago, when he went to audition for a slot at The Comic Strip, in which Wachs has a partnership.

“He was cocky, this kid,” Wachs says. “He complained we wouldn’t let him get right up. He was full of himself. I told him, Too bad; come back later.’ He waited. He worked the club. I knew.”

He evolved with the speed of grass growing in time-lapse photography. He had that thing, that protected adolescent assurance, that sense of his own lightness and assured existence—undisturbed and unscarred—that transmits.

Eddie Murphy came flying out of either heaven or Hempstead, Long Island, about two years ago, and when he auditioned for and won his place at Wachs’s club, he already had what he needed, which was not his wit so much as this presence he had.

“I mean, I couldn’t believe it,” Wachs says. “His material was a little rough, but he had this smile and this voice.” He was the kind of property developers search for for years, Wachs could see, and he’d walked into his club. From where had he walked? Directly from his childhood, from his adolescence, with no stops or crises—no military, no sputtering first marriage, no nights broke and alone (good for him!) in cities whose names sounded Venusian if you said them more than twice. Eddie Murphy was, they say, a happy kid. He stayed close to home. He played ball with Clinton Smith. He got his comedy training where most young comics got their training, in high school.

“We just cut up all day,” says Clinton. “I mean, that’s what we did all day in Roosevelt High; we just cut up.” Clinton is a head shorter than Eddie, and quieter, but the two—as it happens when you meet somebody the same age at the right moment—telecommunicate. They have a merged sense of humor. They can finish each other’s sentences, and this may have happened due to the circumstance of their meeting: On the first day of gym class in seventh grade, for some nearly inexplicable reason, Clinton Smith ran up to little Eddie Murphy—just as though they had been in Little Archie Comics—and jumped on his head. Instead of throwing him off, little Eddie found this act tremendously funny, and in the years since, it has served as a reasonably exact statement of their relationship: Clinton sits on Eddie’s head, serves as a lookout, absorbs Eddie’s jokes, sends down his own. High school continues to be the central informing experience in their lives.

“After a while,” says Clinton, “they stopped expecting us to go to all our classes. We’d just walk by. No one wanted to work. They’d rather be laughing all day than learning geometry.” Roosevelt High became their comedy club, their chance to work on material and find out where the laughs came. They worked assemblies and classes like professionals. Eddie was good, better than anyone else in school and, he found out, better than any of the comics working in local clubs.

He began playing small rooms around town, talking it up in bars, and then he moved into showcases. On Long Island, he played the East Side Comedy Club and Richard M. Dixon’s White House Inn, a club built by the Nixon impersonator. “The first night he went on,” Clinton says, “he was better than almost anybody else there, better than comics who had been working for a long time.” He worked for a while in a group called the Identical Triplets; the joke was that Eddie was the only black. He went back to the East Side Comedy Club over and over and, finally, decided to go to The Comic Strip in Manhattan. It might not have been big-league pitching, but it was closer.

Wachs and his partner, Richie Tienkin, saw Eddie and sent him down to work another club they owned in Florida. “He didn’t tell anybody he was up for the Saturday Night Live slot,” Clinton says, “and then, when it came through, he was mad it was only a featured slot and not full-cast-member status.” Eddie put off college and went to work.

He made it, nevertheless—and his featured status was the best thing that could have happened. Jean Doumanian’s one-year tenure as producer of Saturday Night Live, the year after Lorne Michaels left, became one of the biggest car wrecks in television history. It was instantaneous and the debris was flung through the entire landscape. As the man in the rumble seat, however, Eddie flew into the air, stayed up and, when he came down, landed in a big limousine with the new cast of the revamped 1981–1982 Saturday Night Live. He was no longer featured; he was billed as a star.

Most of all, he had that smile that was ice cream on the eyes, that turned the show into his show, the smile that was like a curtsy after even the most vicious sketches.

Eddie Murphy smiled on camera and Eddie Murphy became a star. He evolved with the speed of grass growing in time-lapse photography. He had that thing, that protected adolescent assurance, that sense of his own lightness and assured existence—undisturbed and unscarred—that transmits. He spoke twice as loudly as anyone else on the show and he enunciated, and his words came flying to the ear as though varoomed through an exceptionally powerful shotgun. He could, it seemed, do almost anything—give delicacy or power, imitate or establish character, intimidate or embroider. Most of all, he had that smile that was ice cream on the eyes, that turned the show into his show, the smile that was like a curtsy after even the most vicious sketches.

In the first few weeks of the show, the writing was better than it had been the season before—but it was bad and disjointed, nonetheless. The old Saturday Night Live—well, you know about that: It was a good ball club, hitting .310 as a team. The next crew put together a black hole of a show, and the one after that did not really seem to be an entity unto itself. It was the Ford Administration shuttled in in an emergency, and it did its work, gaining a nation’s mild thanks. Eddie, however, did better.

Who knows why? Eddie was the only member of the cast who knew how to look the camera in the eye and speak to it. Handsome and loud, distinct and telegenic, he liked being on television. Most of all, Eddie—knocked about less than any other member of the cast, by far the youngest—had the inner rebellion and the egotistical self-righteousness about the material; and, somehow, his attitude toward authority, his self-respect and his individuality registered on the air. Somehow, bad assignments and rotten lines seemed to roll off him as his comedy sense took over; while he worked faithfully, without mugging or overtly separating himself from no-laugh pieces, he somehow communicated a belief in himself as a person and as a hard-working comic who made the tattered spots on the program seem beside the point. He somehow made you think, Well, there’s Eddie Murphy working with that bad stuff, poor little orphink. He grinned with the sense of a valiant against the worst odds, and it made him his own man on television.

And, in fact, some of the sketches were just right for him. In the first weeks of the show, he was handed a few pieces of the kind that people don’t forget. A sketch on literary prisoners in the wake of the Jack Henry Abbott incident had Eddie reading a poem from jail called Kill My Landlord (“C-I-L-L—kill my landlord/Kill my landlord”), and it was right on target, and audiences went crazy for it, and for Eddie.

In other shows, he wrote his own stuff: He played Buckwheat of The Little Rascals without distancing himself from the subject, which would have ruined the joke. A generation of black comedians preceding him could never have put on the Buckwheat wig and gone into his disconsonanted speech—Dick Gregory and Bill Cosby (though neither was a sketch comic) had to establish their dignity as stand-ups, not abandon it—and those comedians had cleared the forest for Eddie. As a child of television, Eddie, in his version of Buckwheat, was no more dangerous than Robert Klein had been in his Little Rascals sketch ten years before. Eddie’s Bill Cosby imitation, however, had a devastating edge to it that built a prickling, fascinating border between himself and the Big Daddy of black comedians.

Eddie would put on a loud V-neck sweater, a suit and a pair of tinted sunglasses, and he’d hold the requisite Las Vegas cigar, bringing in his lips to the Cosby huckster smile and winding on and on with a jokeless story that had no punch lines. Eddie had told a Sepia magazine interviewer that “morally … I admire the shit out of Bill Cosby. You don’t pick up the paper and read Bill Cosby shot his dog or some shit like that”—but he did not admire his comedy. It said a great deal about Eddie Murphy that he admired the most bourgeois black comedian of his moment (Las Vegas; commercials for Ford, Jell-O, Coke—a portfolio almost too full to believe) but expressed displeasure at his skills as a comic. Not only because of his values but because of his belief in product, Eddie Murphy was no rebel; he was a comedian of the middle class, a young American for his own freedom.

Somehow, in a perverse way, Richard Pryor, whom Eddie worshiped, had paved the way for all of that. Pryor had made the transition that Hollywood loved most: From magnificent comedy terrorist, he had somehow become a fierce house pet of the industry. He had been scary and uncontrollable, then he became an element in the business; he achieved success on Hollywood’s terms without alienating his own audience. And so Pryor, who had been angry and wild and a great pioneer of street-war guerrilla comedy, somehow became a Ray Stark product in Hollywood, working his way into suburban theaters as (the market researchers must have had the triumph of their lives with this one) Cosby’s black-bourgeois tennis foe in the disgracefully conceived third segment of Neil Simon’s California Suite. Pryor had been moved by forces bigger than himself and brought into the value spectrum of the Hollywood power guard. You can’t say anything was wrong with it; he was just turned into a star (in fact, a superstar). Before that, he had been an unplaced part, as a turbo engine would have been if it had shown up at an airplane factory in 1926. Once the industry caught up with him and he became fitted, he also became part of it all—neither a mad rebel with a red flag nor a prophet around whom the disaffected might rally.

The black comedian, the very black comedian in America, had finally become commercial. Americans were ready to acknowledge the fact that they shared his distance from their national destiny; that alienation had become sufficiently funny to join; that blacks represented all of us more than anyone had wanted to admit for the entire nightmarish history of the race wars in the United States. Pryor was the first to come home with the news; his genius had taken him the last mile, and the money men had spotted it. Eddie Murphy, as his most talented suburban black successor, would be the second to slide home free, without terrible compromise, without having to hand over his blackness, without having to make the high, bloody fight of his courageous predecessors, either. Unlike Dick Gregory or Lenny Bruce or Pryor, Eddie Murphy would have to make no Custer’s Last Stand of comedy; he would be allowed to be a star as other comedians were allowed to be stars. He would not have to open up his organs in order to do it.

Yet one felt that if he had to, and if he’d been made to, Eddie might have done it. He had strength and intelligence and the arrogance he needed in case there were ever a moment—in a crisis—in which he had to reach down and call on it. He liked to yelp and rebel and he was good at it, and there wasn’t a person who knew him who didn’t suspect that what he was displacing at the moment was a resolve that had shown up often, in the younger days of his very self-made life as a comedian.

“He was always that way,” his mother says, sitting in a basement room in her Long Island home. A huge poster of Eddie looks down at her and her husband—who, as a former professional boxer, is following the Saturday afternoon bout on television with a manager’s attention. “He always just wanted to do his own thing and took no guff from anybody. He liked to do things his own way and see things his own way. He was a friendly little boy, but he didn’t like to be told what to do.”

“That’s right,” says Clinton Smith, “he just did, and he knew exactly what was right for him and didn’t let anybody tell him he was wrong.”

Eddie and Clinton and Bob Wachs sit in a recording studio listening to the tapes from Eddie’s Comic Strip nights.

“Do you think,” Eddie says, “this can win a Grammy? What wins Grammies?”

“I don’t know,” says Wachs, “but I think it can go platinum—gold, at least, but maybe platinum.”

The album is what Sam Lefrak has put his money on—a traditional launching-the-comedian christening in which Eddie does live-concert material, plus two studio songs, one of which has him singing a duet featuring Buckwheat and another of his TV characters, Little Richard Simmons, the other a hyperbolically accelerated black rap song with dirty lyrics.

A Falkland Islands report is on television in the next room. Eddie goes out to watch it for a moment. He listens to all the takes on the record and chooses surely. He knows what sounds good and what is funny. He lies on a couch in the studio while Wachs and Clinton sit, and he puts a finger in the air when he likes something he said.

His taped voice comes through the speakers: “Anybody count how many times I said fuck tonight?” The audience on the tape laughs.

“I’d like to know,” says Eddie, lying on the couch. “About every other line.”

Wachs is making notes on the tape.

“Fuck,” says Eddie, getting up. “I’m 21, man, and my back hurts.” He stands up.

“I’ll tell you,” he says, “I’m tired. All this shit, all these people. I just don’t know.” He listens to his voice on the tape. “Johnny Carson summed it up,” he says. “When I was on the show, he took me aside: ‘You don’t change; the people around you change.’”

Wachs makes some more notes. Clinton looks up at Eddie. Eddie’s taped voice comes on.

“That’s good,” he says, listening. “That can be a single cut.”

“You think so?” says Wachs. “I don’t know; I think it can be a lot of little cuts.”

“A single cut,” says Eddie Murphy.

They are due uptown in a half hour for a recording session at the RCA studio for Boogie in Your Butt, the rap-song parody Eddie will record. Eddie and Clinton decide it may be a good idea to have some Chinese food before the recording session.

“I need some Chinese duck,” Eddie says.

“That’s good,” says Clinton.

So the three of them walk to a restaurant in the West 40s, Wachs leading the way. They sit down and begin their favorite dialogue. Eddie and Clinton are suddenly two washed-up blues singers in their 60s visiting New York. They talk in old-man-Southern-blues-singer voices and speak only to each other.

“It’s good bein’ in New Yawk,” Eddie says.

“Mm-hm,” Clinton says. “Is good.”

“But problem is,” Eddie says, “no house here is good enough to play us anymore. No house.”

“No house that good,” says Clinton.

“Now, take those other singers, what their name? The uh, the uh—”

“I know who you mean,” Clinton says.

“They washed up.”

“Washed up.”

“Not us,” says the 60-year-old Eddie. “We goin’ strong.”

“I’ll say,” says Clinton. “We stronger than ever.”

“We’d play this town if it was worth playin’.”

“Yeah—but it ain’t.”

“No, no, but I’ll tell you somethin’.”

“What’s that?”

“We goin’ to.”

“I know.”

“Someday soon, we goin’ to.”

“We goin’ to good.”

“All we need’s a good enough house.”

“A good house.”

“And we’ll pack it, pack it right up to the top. ’Course, we need a good manager, too, you know.”

“Don’t you know that’s true?”

“You like this here rice?”

“I like it. I like this pork and these spareribs.”

“I like ’em, but I’ll tell you.”

“What?”

“We need a good house to play in.”

“That’s right.”

“Uh-huh.”

“Mm-hm.”

“Remember Kansas City?”

“I do. I remember it good.”

“We had a good house there.”

“We did.”

“This good egg fooey.”

Wachs looks around for a waiter, looks desperately for a check. Eddie and Clinton fade deeper and deeper into old-man personae.

“You lookin’ good.”

“I know.”

The two of them get up and begin walking out of the restaurant. Eddie pays the bill. They walk down the street toward RCA, huddling deeper still into the old bluesmen and, finally, Wachs stops.

“All right, guys, just stop it. Let’s go in.”

“You hear him?” Eddie says in an old, old voice.

“Hear what?” Clinton says.

“That man.”

“What man? Where we goin’?”

Eddie puts his hand on Clinton’s shoulder and the two black sunshine boys get into the RCA elevator.

“We goin’ up,” Eddie Murphy says.