Bill Buckner came to the big leagues as a headstrong kid who could outrun everything except self-doubt and hobbled out of the game under the longest shadow a simple ground ball ever cast. But it was between the poles of his career, when Los Angeles was in his past and no one knew what awaited him in Boston, that the essential Buckner emerged as he defied the melancholy that draped Chicago’s Wrigley Field like funeral crepe every September.

There were no pennant races for the Cubs teams he played for in the late ’70s and early ’80s, no roaring crowds to hail his refusal to surrender to the franchise’s then-dreary tradition. The days grew shorter as futility set in relentlessly, and anyone in need of a nap could find plenty of room to stretch out in the bleachers. “It’s like somebody turns off the electricity every August 31st,” Buckner once told me, but he would have none of it. A heart the size of his didn’t come with an off-switch.

So when I heard the news that Buckner had died yesterday at age 69, my first thought was not of Mookie Wilson or World Series victory denied. It was of Buckner stepping to the plate wearing the dirtiest Cubs uniform on the field. He stares out at the pitcher from beneath eyebrows that are the perfect complement to his bushy mustache. Wrigley is still without lights, and the fading sunshine mocks the grease that he has smeared beneath his eyes to cut the glare. Maybe that’s why the pitcher in my memory tries to sneak a fastball past him. But reasons count for nothing in baseball. Only results do.

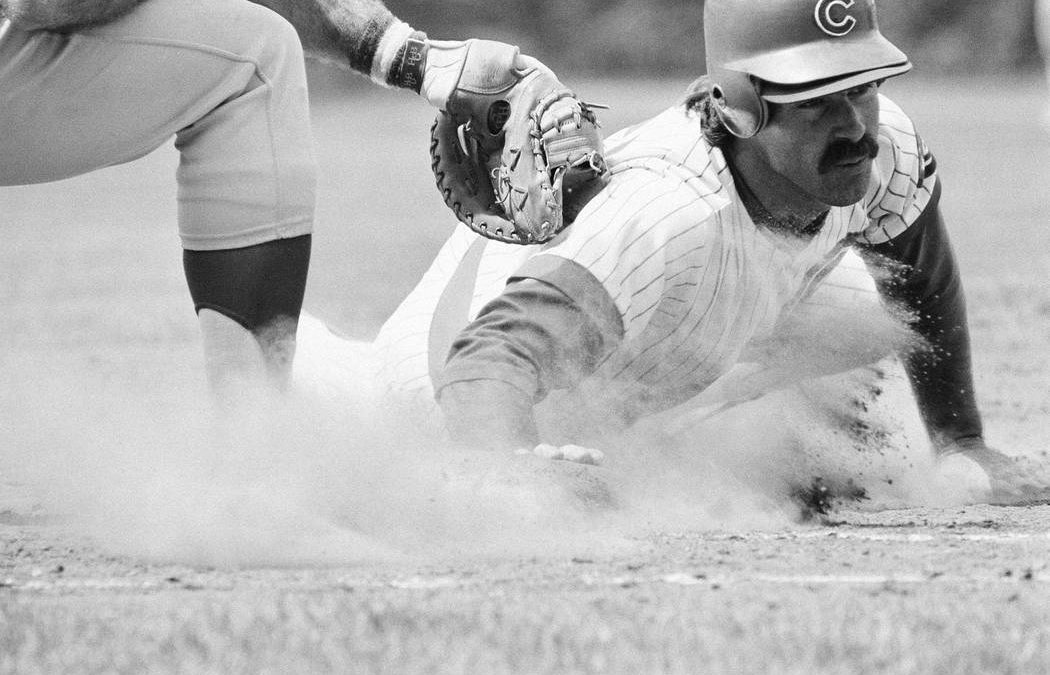

Buckner lashes a line drive to left-center field, the sort of shot that was his calling card for 22 big league seasons. Scuttling out of the batter’s box with a ruined ankle begging for mercy, he’s hunched over, almost crab-like, yet hell-bent on ringing up another double. And when he slides safely into second base, he has done more than spit in the eye of the Cubs’ lost season. He has offered us a symbol of everything we should treasure about him as a baseball player.

There are statistics involved, of course. What would the grand old game be without them? In the case of William Joseph Buckner, he won the 1980 National League batting championship with a .324 average. He also led the league in doubles twice, and then moved on to Boston, where he hit 46 of them in 1985 and somehow managed not to lead the American League. He drove in more than 100 runs once with the Cubs and twice with the Red Sox. When you realize that 18 home runs were the most he ever hit in a season, you come to understand just how tough he was in the clutch. And one other thing: in his youth with the Dodgers, when he had yet to go under a surgeon’s scalpel, he stole as many as 31 bases.

Add up all the numbers and you will find that he batted .289 for his career while pounding out 2,715 hits. That’s more hits than Ted Williams, Joe DiMaggio and about 70 percent of the other sweet swingers in the Hall of Fame. And Buckner played in more games than Babe Ruth, Rod Carew and Willie Stargell. You can look it up: 2,517.

That’s not to say Buckner was better than any of the legends mentioned above. He wasn’t. But to paraphrase what an admiring A.J. Liebling once wrote of a boxer who was never a champion, he was as good as a ballplayer can be without being a hell of a ballplayer.

The Dodgers expected no less when Buckner arrived in L.A. in 1969 as a 19-year-old first baseman. He was one of the team’s golden children, shoulder to shoulder with Steve Garvey, Ron Cey, Bill Russell and all the others who set a standard that no subsequent youth movement has equaled. Moved to the outfield, he responded by batting .300, running as if the cops were after him, and howling in anguish every time he made an out. “What’s the matter?” the imperturbable slugger Dick Allen asked during his one season on the team. “You act like you’ll never get another hit.”

As a matter of fact, that was exactly what Buckner thought. Such was the force that drove him. “After a while,” he told me, “you start wondering how much you fear failure.” He feared it beyond reason because it suggested he wasn’t bearing down, wasn’t investing body and soul in every time at bat. A trick of the mind, perhaps, but it helped him become everything he could be on a baseball diamond. Everything except lucky.

The ankle Buckner tore up in L.A. was the first sign that no road is without potholes. He went to Chicago in 1977, a first baseman once again, and hobbled every step of the way. “Like a hundred-year-old man,” he said. He wore high-top baseball shoes for support and was the first man at ballpark every day just to get himself stretched out enough to play. The doubles, the RBIs, even the batting title – none of that could numb the pain he felt and never talked about for public consumption.

He moved on to Boston in ’84 and found balm for his competitive spirit in a city where there really were pennant races and, two years later, a World Series. But he hurt in more places than ever, and the pain was etched in his every step. He didn’t beg out of the line-up, though, just kept grinding at the plate and at first base. Then came the ’86 Series and the fateful ground ball off Mookie Wilson’s bat. It was as though every good deed Buckner had ever performed was erased when that ball – that damn ball – wormed its way through his gnarled legs.

Never mind that he shouldn’t have been in the game by that point. Never mind that a young and nimble defensive replacement should have been out there while Buckner watched from a dugout ready explode with happiness. Never mind the myriad other reasons why the Red Sox lost the game and the Series. Buckner was the fall guy.

He remained one until the Boston faithful reined in their sense of betrayal and accorded him the respect he was due. For here was a man who embodied the spirit, passion and indomitability that are baseball’s lifeblood. To watch him whether he was young and whole or battered and long in tooth was to know he was that most prized species, a big leaguer who played as hard as the fan in the stands imagined he would if their roles were reversed. He may have feared making an out, but he never backed down from the pain that refused to go away. If that sounds like an epitaph, so be it.

John Schulian is a former Chicago Sun-Times sports columnist and the editor of the newly-released Library of America anthology The Great American Sports Page.