Greatness takes a physical toll on all those who achieve it. So it is a testament to Pelé’s courage and indomitable will that this month he will mark eight decades on the world stage after years of being battered by the game’s hatchet men and a series of recent medical issues. Eight by Eight Writer-at-Large David Hirshey who has known Pelé since 1975—and collaborated with him on a memoir—pays tribute to the man who forever transformed the sport in his own joyous image.

A GOD IN WINTER

The Enduring Legacy of Pelé

Dressed all in black save for a garish gold bowtie, each earlobe festooned with diamond studs and each wrist adorned with a bejeweled watch, Diego Maradona arrived at the Kremlin looking like a Bond villain masquerading as a butler. Oozing past a gaggle of earpiece-wearing Russian goons, the argentine icon planted himself first in line to greet that evening’s host.

It was December 1, 2017 and that host was Vladimir Putin, the notoriously bare-chested equestrian, judo sensei, Trump puppet master, and, of course, president of Russia, site of the 2018 World Cup. Putin had invited the “living legends” of World Cups past to this private reception just hours ahead of the tournament’s ceremonial draw.

Up the red-carpeted staircase they went, a cavalcade of aging soccer deities. Some, like Gordon Banks, England’s 1966 World Cup–winning goalkeeper and now a snowy-haired, stooped octogenarian, struggled to make the climb. Others, like the Brazilian wonder boys of the 2002 World Cup, Ronaldo and Ronaldinho, seemed as spry as the day they left the pitch. There was a swagger to their gait and a swivel to their hips, although Ronaldo appeared to have spent much of his retirement chained to a buffet table.

At the center of them all was Maradona, who had anointed himself a one-man Putin-fawning band for this special occasion. When the Russian despot finally emerged, Maradona greeted him with whatever passes for “Sup, bro” in Spanish. As Putin raised a glass of champagne to the assembled legends, Maradona grabbed the Russian’s other hand and, weirdly, wouldn’t let go.

Putin’s flinty gaze had already shifted to the opposite end of the room, to someone he seemed eager to greet—or possibly to have arrested, given that he was the only guest not standing in the presence of the former KGB chief. Abruptly, Putin freed his hand from Maradona’s grip and crossed the floor to his seated target. At which point the master of Russia did something wholly unexpected: He actually bent—no, bowed—down and clasped the man’s hand. It was Pelé’s hand, after all. And Pelé, even to Tough Guy Putin, was O Rei, the King of Soccer.

Pelé responded to the Russian’s affectionate greeting with the same warmth he had shown to two Popes, five emperors, 10 monarchs, and 108 heads of state over the course of his incandescent career. Although that career ended long ago, Pelé’s luminous smile, irrepressible bonhomie, and even his hair have remained intact—as jet black as it was in the 1958 World Cup final between Brazil and Sweden, when a scrawny, unknown 17-year-old first blasted off into the soccer stratosphere.

The rest of Pelé, however, had changed dramatically. Those heavily muscled legs that used to whir nonstop while cutting apart an opposing defense were as limp as overcooked noodles. His preternatural gifts—the propulsive speed, the fearsome power, the gravity-defying balance, the feline grace—all gone. The image of Pelé that had long endured in my mind’s eye—body arcing high off the ground, arm cocked in that signature goal salute, head thrown back in jubilation—was suddenly replaced by a frail, old man, unable to walk or even stand on his own. In the past five years I’d interviewed him twice; on both occasions he joked about his “new soccer shoes.” The first time it was a cane, then a metal-framed walker. But watching the video of Putin’s fete, I wasn’t prepared for the visceral jolt of seeing him in a wheelchair. It felt like a gut punch.

Pelé had been the lodestar of my soccer dreams, the reason I fell in love with the sport when all the other kids were besotted with Mickey Mantle and Willie Mays. I was lucky enough to see him play in his all-conquering prime for Santos and in the gloaming of his career with the Cosmos. I also spent two years collaborating with him on a memoir, shadowing his every move as he crisscrossed America to spread the gospel of soccer to the last place on the planet immune to its charms. Hell, I even hung out with him (albeit briefly) at the fabled disco Studio 54 the night Grace Jones played Lady Godiva, riding naked across the dance floor on a white horse.

To be in the presence of the beautiful game’s most beautiful player, to hear him say, “How are you, my friend?” sounded like a benediction. I once asked him if he utters those words to everyone he meets. “Not everyone,” he replied, grinning mischievously. “That would be about half the people in the world.”

The other half, I figured, must have been Maradona fans.

Over the decades the two epoch-defining players have often engaged in a petty, sometimes rancorous schoolyard feud (I’m the best ever! No, I am!) fueled by FIFA’s boneheaded decision to honor them jointly as Co-Players of the 20th Century.

In the past few years, though, there’s been a thaw in their relationship based on mutually beneficial shilling—and the shared dread that Lionel Messi may have eclipsed them both. So when Maradona glimpsed Pelé posing with Putin for the snap-happy paparazzi, the Argentine scurried over to his longtime enemy and gently kissed his forehead. Pelé appeared momentarily stunned, his expression somewhere between bemusement and suspicion. Had the former coke fiend and all-around vulgarian—who had once told the Brazilian to “suck my dick”—suddenly become his BFF? Or was Maradona just photo-bombing a sure-to-go-viral shot of Pelé and Putin?

Pelé seemed not to care. He was simply eager to leave the media circus behind. With the aid of his compatriot Ronaldo, he rolled into the Kremlin’s concert hall, where FIFA delegates, B-list celebrities, and Gary Lineker were waiting for the World Cup draw to begin. As as he entered the cavernous room, spontaneous applause broke out. Pelé let the adoration wash over him and waved regally. He was still O Rei, the King, even if his throne now had wheels.

Pelé is well into storage time of an extraordinary life; he’ll turn 80 this month. There is, of course, no telling when the final whistle will blow, but after his most recent near-death episode this past April, when he contracted a urinary infection so severe he spent 13 days in the hospital, one thing is certain: The window to celebrate him while he’s still among us is narrowing.

The once seemingly indestructible Brazilian who tormented defenders with insolent ease is now up against opponents whom he can’t turn inside out: a busted hip, which keeps him in constant pain despite two surgeries; a crumbling spine with extensive nerve damage; one working kidney requiring dialysis; both knees shot through with arthritis and devoid of cartilage.

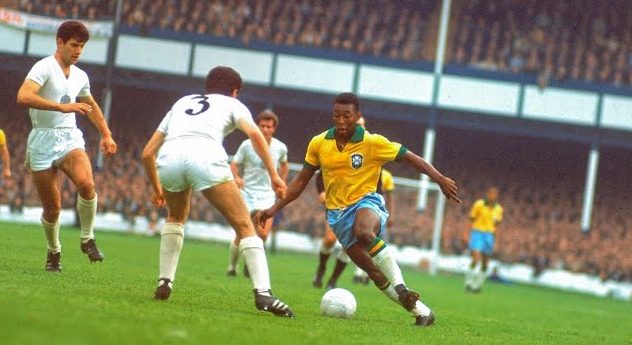

The fact that Pelé has grave physical problems would not surprise anyone who saw him play in his peak years. In those days of wanton shithousery, before yellow and red cards were introduced, he made every defender he ran at look like they were wearing clown shoes. Is it any wonder that his opponents attempted to pull him apart, limb by limb, shredding him like a human piñata? Convinced that he could go around, over, under, or through anybody in his way, Pelé rode those borderline criminal assaults all the way to the hospital.

“Pelé,” he said over the din of the crowd, “is not of this world.”

Pelé’s courage, his refusal not to be cowed by the game’s hatchet men, would inevitably exact a price, and by 1966, the Brazilian knew it. “For me there will be no more World Cups,” he vowed after Portugal’s defenders pummeled him so relentlessly that he was carried off the field on a gurney. “Soccer has been distorted by violence and destructive tactics. I do not want to finish my life as an invalid.”

Yet four years later, Pelé bowed to the pressure of his countrymen to wear the famed canary yellow jersey again. The 1970 World Cup in Mexico would prove to be his apotheosis. At 29, he played the most transcendent soccer of his career, scoring one magnificent goal and making two others in the 4-1 romp over Italy in the final. The game will be remembered for Brazil’s flowing nine-man move that led to the fourth goal, scored by Carlos Alberto, who ran onto Pelé’s no-look, perfectly weighted pass and, without breaking stride, smashed the ball into the net. “Playing with Pelé,” Alberto would say years later, “was like having God on your side.”

The term “unplayable” has become a cliché, attaching itself to anyone who for one game (think Maradona in 1986 against England), maybe even for one season (see Cristiano Ronaldo’s 60 goals in 2011–12), is performing at such a ludicrously high level that opponents are helpless to stop him. But you could say of Pelé that he was unplayable for almost 15 years, starting in 1958 and continuing through and beyond the 1970 World Cup, a run of sustained brilliance unparalleled in the sport’s history—until that little guy in a Barcelona shirt dropped from the heavens.

So who is the best player ever? The GOAT (Greatest of All Time)? I could make a case for Pelé, but that would only spark the MTOASD (Most Tedious of All Soccer Debates) and, frankly, I’d rather chew off my arm.

We live in an age of instant hot takes that measure everything in binary terms—winner or loser, thumbs up or down. There is no time for nuance in the social media era. Ours is a Messi-shaped universe with YouTube streaming his every are-you-fucking-kidding-me goal in real time. Pelé, meanwhile, belongs to a prehistoric era of yellowing newsprint and grainy black-and-white videos. Every four years, the most obsessive watchers of the World Cup might be rewarded with a glimpse of his exhilarating artistry during a historical montage, but that’s it. Forget seeing him in high definition or on TikTok. Pelé exists only in the memories of those who saw him play.

My millennial daughter sometimes invites her friends along when she visits. They are annoyingly pop-culture-literate, and these days that includes being reasonably conversant with quadrennial global spectacles like the Olympics and the World Cup. Recently one of them spotted the signed Pelé jersey framed on my office wall. He asked my daughter, “Why does your dad have an autographed shirt of the guy who does those Viagra commercials?”

Yet for those of us old enough to have borne witness to the Brazilian at his celestial height, Pelé is the benchmark against which all the other supernovas—Puskás, Di Stéfano, Cryuff, Beckenbauer, Maradona, Zidane, Ronaldo, and, yes, Messi—are judged. He was the first global soccer celebrity and the personification of joga bonito, the free-wheeling, joyful style that set Brazil apart from all other national teams, which preached structure and system at the expense of individual creativity. The 1970 World Cup champions with Pelé, Gerson, Tostão, Jairzinho, Rivellino, and Alberto were as close to Soccer Nirvana as we’re ever likely to get.

Pelé won three World Cups with Brazil and was the dominant force in two of them. He scored a staggering 1,281 goals for club and country (OK, a couple hundred of those were against the roadkill that Santos played in the 1960s, when the Brazilian club was soccer’s equivalent of the Harlem Globetrotters.)

His misses were often more beautiful than the goals others scored. Against Uruguay in 1970, he stretched the boundaries of logic as far as humanly possible. Racing toward a seeing-eye through ball from the diminutive center forward Tostão that put him one on one with Uruguay’s standout goalkeeper Ladislao Mazurkiewicz, Pelé appeared to have two choices: 1) chip the hard-charging keeper while running at full tilt; 2) drop a shoulder and dribble around him.

He had a fraction of a second to make those calculations. The thing about Pelé, though, the quality that made him sui generis in his day, was that his brain was as quick as his feet. “Pelé is still the only player who can think twice in one second,” the Uruguayan defender Alfredo Lamas once said of his Cosmos teammate.

Pelé dismissed the two expected options, even though either maneuver would doubtlessly have resulted in an easy goal. But where’s the fun in that? In that instant, he had the audacity to reach for soccer perfection and rip a hole in the space-time continuum. Isn’t that what genius does? Make the abnormal look normal, the ridiculous appear routine?

As Pelé and Mazurkiewicz converged at the top of the box, the Brazilian decided not to touch Tostão’s pass, instead letting the ball roll by the keeper’s left side while he circled him on his right. I wish I could tell you that after Pelé left Mazurkiewicz flailing helplessly on his knees and looking behind him at his vacant goal, he then collected the ball and deposited it in the empty net. But the truth is, he missed. His off-balance shot trickled past the far post by a centimeter, making it the greatest goal never scored in World Cup history.

It’s easy to forget that all of Messi’s outrageous shimmies, wriggles, jab steps, shoulder dips, pirouettes, nutmegs, and sombreros that he deploys to effortlessly skip by defenders didn’t just spring full bloom in soccer’s modern age. They are the natural extension of what the Brazilians call “ginga,” the rhythmic swaying of the hips and samba no pé (“samba in the foot”). It took Pelé and his bandy-legged teammate Garrincha, perhaps the greatest dribbler of all time, to bring this musical expression of soccer out of the favelas and into prime time at the 1958 World Cup. Messi may have made these moves his own, even added some hot sauce for good measure, but he didn’t invent them.

You always remember your first time, especially when you feel the earth move. In my case, an entire stadium shook in ecstasy, induced by Pelé. It was 1968 and Santos was on a “Pay to See Pelé Play 20 Minutes” tour of the United States. My father took me to see them play Benfica at Yankee Stadium in New York.

The match was billed as Pelé vs Eusébio, or “the Black Pearl of Brazil” vs. “the Black Panther of Portugal.” What a way to finally behold my childhood idol in the flesh, rather than through a fuzzy tiny TV screen. Eusébio had been ordained Pelé’s successor in the global firmament after scoring four of Portugal’s five goals in a remarkable comeback against North Korea in the 1966 World Cup. Neither player had expressed anything but the most profound respect for each other—privately, though, the Brazilian had a score to settle. While Eusébio played no part in his country’s vicious fouling of Pelé in ’66, he was the face of the Portuguese team that battered him out of the tournament. Karmic payback was in the air.

Late in the first half, the Brazilian stood near midfield, the ball at his feet, facing Eusébio. At that moment, it felt like everyone in Yankee Stadium was poised over that stationary ball, as if Pelé had simply frozen time and motion to reassert his supremacy. He waited for the Portuguese star to lunge at the ball as he knew he would—and at that instant slipped it between Eusébio’s legs with a flick so casual he could have been brushing a piece of lint off his shoulder.

The nutmeg is soccer’s ultimate burn, and by humiliating Eusébio and then gleefully racing off with the ball down the pitch, the Brazilian was sending his Portuguese rival a message: “I’m Pelé and you’re not.” From every corner of the old ballpark, his name came cascading down—“Peléeeee, Peléee, Peléee!” It was as if 36,000 people were hugging him with their voices. I had never seen my father go quite so bonkers at a sporting event. Born and raised in Europe, he had played and followed soccer all his life and thought he had already witnessed the game’s acme as embodied by the immortal Ferenc Puskás and Hungary’s Mighty Magyars. Now, at Yankee Stadium, he had glimpsed an even higher dimension.

“Pelé,” he said over the din of the crowd, “is not of this world.”

My father’s words seemed eerily prescient seven years later when Pelé descended out of the sky, deus ex machina. It was May 28, 1975, 12 days before His Onlyness would sign a three-year $4.7 million contract with the Cosmos—the highest salary of any soccer player in the world at the time. I’d been tipped that Pelé would be attending that day’s game against Vancouver as a guest of the New York club. I showed up two hours early, just in time to catch sight of a helicopter touching down a hundred yards behind the goal at the south end of the Cosmos stadium. When the future Pied Piper of American Soccer disembarked, he could scarcely believe what he saw: a pile of dirt and rocks that looked like it had been left over from the Paleolithic era. Welcome, Pelé, to New York’s Randall’s Island! Michelangelo had the Sistine Chapel; Pelé had a sludge heap rising out of the East River.

And yet two weeks later, in his first scrimmage with his new team, the Brazilian managed to paint his own masterpiece on this primitive terrain.

At 34, eight months removed from a competitive match after retiring from Santos in October 1974, he could not summon the miracles as easily as he once did. So Pelé initially hung back in midfield, orchestrating the action and shouting the few English words he knew—“Ok, Ok,” and “Easy, now, look, look, look the ball”—to his starstruck Cosmos teammates, all of whom had developed two left feet in his presence.

About 30 minutes into the game, Pelé suddenly reached back across the years and pulled a face-melting moment of joga bonito from his memory bank. The play started on the left flank, when the smurf-like Scot Johnny Kerr sent a shoulder-high cross-field ball to Pelé, who was lurking in the box. He sat back for a second or two, his squat body reclining as if in a beach chair, then with his left leg floating up, his right leg catapulted him into the air, his back parallel to the ground. He scissor-kicked sharply, caught the ball with his right instep, and drove it over his laid-out-flat body into the goal.

“What just happened?” said Cosmos goalkeeper Kirk Kuykendall.

It would be nice to report that soccer’s supreme evangelist came to America because he couldn’t resist the challenge of converting the heathens, one bicycle kick at a time. Nice but not true. Fact is, Pelé needed Yanqui dollars—a lot of them—to build back the fortune his financial advisers had lost through disastrous investments. But before he would put pen to paper Pelé had two specific demands: He wanted the money in cash, and to avoid messy tax issues in Brazil (the government had already deemed him a nonexportable national treasure) he didn’t want to be identified as a soccer player.

Warner Communications, the team’s parent company, rejected point one, agreeing instead to heavily front-load the contract. They accepted point two, though implementing it would require some ingenious corporate maneuvering. Atlantic Records, one of many entertainment companies under the Warner umbrella, was run by Ahmet Ertegun and his brother Nesuhi, lifelong soccer aficionados from Turkey. Along with Cosmos president Clive Toye, the Erteguns had been largely responsible for capturing soccer’s biggest prize. They would overcome the last contractual obstacle by listing Edson Arantes do Nascimento as a “recording artist” for Atlantic. The workaround wasn’t even that far-fetched. Pelé often spent his idle hours strumming his guitar and composing songs, some of which had been recorded by Brazil’s biggest pop stars.

After two years of traveling with Pelé on planes and in limos, I finally realized there was something he liked even more than music: sleeping.

“Once, I see him sleep from Brussels to Tokyo,” said the Peruvian midfielder Ramón Mifflin, who played with Pelé on Santos and the Cosmos. “You know how long this is? Twenty-six hours, half a world. Pelé never open his eyes.”

Of course, someone who can send a defender spinning off the edge of the earth is surely capable of feigning sleep. Who could blame him for wanting to close off a world of fans determined to talk to him, touch him, bear his love child? Enter Pedro Garay, Pelé’s bodyguard, who, among his other duties, was charged with fending off El Rei’s legion of admirers. A stocky bundle of tensile strength, Pedro was Cuban, a veteran of the Bay of Pigs. For his boss’s protection, he carried a leather-wrapped, lead-filled “slapper” with him at all times. When it came to the ladies, however, Pedro was all Latin charm. In a Toronto hotel one night, I heard a ruckus at the other end of the hall, where Pelé’s suite was located. Pedro was demanding to search a chambermaid’s laundry cart, which looked unusually bulky. Sure enough, Pedro unearthed two half-naked females hiding beneath the pile of fresh linens. “Does Mr. Pelé need to have his bed turned down?” one of the women asked.

“No,” Pedro said firmly, “but my room is right next door.”

With Pelé smashing attendance records wherever he went, even the most soccer-illiterate swine—like, say, the xenophobic editor at the New York Daily News who told me not to waste my time on “a game for commie pansies”—could no longer ignore the seismic upheaval Pelé was having on the country’s sporting landscape. Pre-Pelé, the Cosmos were drawing fewer than 6,000 fans and giving away free seats with each purchase of a Burger King Double Whopper. In his third and final season, 77,691 delirious converts watched the Cosmos play the Fort Lauderdale Strikers, a number more than triple that day’s attendance for the New York Yankees.

By then, the Cosmos had left decrepit Randall’s Island for swankier digs: Giants Stadium in New Jersey. And Pelé, for all his eye-catching flicks and subtle back-heels, was no longer the goal-scoring predator who swooped down in the box with hawk-like rapaciousness. At 36, he’d become more of a creative fulcrum, his 18 assists in 1976 shattering the North American Soccer League record yet failing to lift the Cosmos to the title he so craved.

On another night in another city, this one Seattle, Pelé was uncharacteristically pensive. “I wonder if I fail in my mission, to bring soccer to the American people,” he mused as we sat in his hotel suite. His feet, badly blistered from his first encounter with an Astroturf field, were cooling off in an ice bucket. “To do this we must have a championship. This team must be the best. Every team I play on, it is the same way. If the team is no good, they will say Pelé is no good.”

[This story appears with the author’s permission; also check it out in the wonderful publication Eight by Eight]