Thanks to Josh Lieberman, check out this trove of goodies from Holiday magazine. Tasty.

“In Defense of Brooklyn” by Murray Goodwin (November, 1946):

Feltman’s is not the only Brooklyn restaurant of repute. Whenever the fishing fleet stands into Sheepshead Bay it brings tender morsels from the sea consigned to restaurants like Lundy’s, Villepigue’s, McGuinness’, and many another famous sea-food emporium. In these places lobsters, clams and crabs attain such heavenly flavor that many a guest has sworn his particular delectable was served wearing a halo.

Where in Manhattan can the hot and tired gentry plunge into the ocean from a six-mile-long frontage of beach? Seek high and low; you’ll find no spot in Manhattan which can offer so much comfort to so many people as can Coney Island. From Manhattan, from the Bronx, they pour into Brooklyn laden with children, paper bags, vacuum bottles, water-wings, patched inner tubes. In myriad tongues they sing their happiness at finding a square yard of tan sand to plump upon, just spitting distance from the surf, and where the sun may fall on them in warm embrace. Brooklyn, with a heart as big as its body, bids them all to try the breakers in the daytime, or seek a thrill at night aboard the giddy roller-coasters, giant swings, and midget dodgem cars.

“Living in a Trailer” by James Jones (July, 1952):

One of the things about writing that lends itself to trailer living is this fact of being your own boss and able to work as well one place as another, and in addition, requiring very little equipment to carry with you. I knew one man in Florida who had the front half of his trailer fitted up as a machine shop with lathes and drill presses and carried his business with him. He had a big trailer, but it still didn’t make for very comfortable living. But he was an exception; mostly they are retired.

“Jalopies I Cursed and Loved” John Steinbeck (July, 1954):

In those days of the Depression one of the centers of social life was the used-car dealer’s lot. I got to know one of these men of genius and he taught me quite a bit about this business which had become a fine art. I learned how to detect sawdust in the crankcase. If a car was really beat up, a few handfuls of sawdust made it very quiet for about five miles. All the wiles and techniques of horse-trading learned over a thousand years found their way into the used-car business. There were ways of making tires look strong and new, ways of gentling a motor so that it purred like a kitten, polishes to blind the buyer’s eyes, seat covers that concealed the fact that the springs were coming through the upholstery. To watch and listen to a good used-car man was a delight, for the razzle-dazzle was triumphant. It was a dog-eat-dog contest and the customer who didn’t beware was simply unfortunate. For no guarantee went beyond the curb.

“A Boy Grew in Brooklyn” by Arthur Miller (March, 1955):

Nobody can know Brooklyn, because Brooklyn is the world, and besides it is filled with cemeteries, and who can say he knows those people? But even aside from the cemeteries it is impossible to say that one knows Brooklyn. Three blocks from my present house live two hundred Mohawk Indians. A few blocks from them are a group of Arabs living in tenements in one of which is published an Arabic newspaper. When I lived on Schermerhorn Street I used to sit and watch the Moslems holding services in a tenement back yard outside my window, and they had a real Moorish garden, symmetrically planted with curving lines of white stones laid out in the earth, and they would sit in white robes—twenty or thirty of them, eating at a long table, and served by their women who wore the flowing purple and rose togas of the East. All these people, plus the Germans, Swedes, Jews, Italians, Lebanese, Irish, Hungarians and more, created the legend of Brooklyn’s patriotism, and it has often seemed to me that their having been thrown together in such abrupt proximity is what gave the place such a Balkanized need to proclaim its never-achieved oneness.

“Living with a Peacock” by Flannery O’Connor (September, 1961):

For a chicken that grows up to have such exceptional good looks, the pea cock starts life with an inauspicious appearance. The peabiddy is the color of those large objectionable moths that flutter about light bulbs on summer nights. Its only distinguished features are its eyes, a luminous gray, and a brown crest which begins to sprout front the back of its head when it is ten days old. This looks at first like a bug’s.antennae and later like the head feathers of an Indian. In six weeks green flecks appear in its neck, and in a few more weeks a cock can be distinguished from a hen by the speckles on his back. The hen’s back gradually fades to an even gray and her appearance becomes shortly what it will always be. I have never thought the peahen unattractive, even though she lacks a long tail and any significant decoration. I have even once or twice thought her more attractive than the cock, more subtle and refined; but these moments of boldness pass.

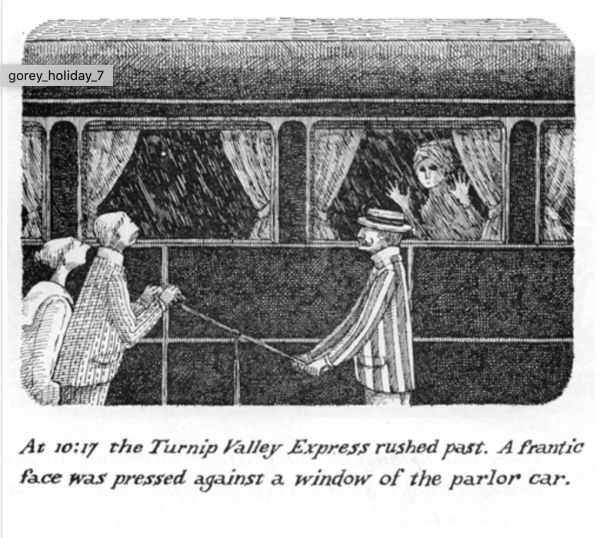

“The Imprudent Excursion” by Edward Gorey (May, 1962):

“New York’s New Tower” by Gay Talese (May, 1965):

Like thousands before him, Tom Kyle came to New York hoping to become a stage star, and like thousands before him, he did not make it. So today, after years of trying and only a few small parts to show for it, Tom Kyle, at thirty-four, works full time behind the information desk in the lobby of the fifty-nine-story Pan Am Building, at Park Avenue and 45th Street. Strangers approach all day with questions like:

“Say, fella, about how many windows in this place?”

“On the Road with Memère” by Jack Kerouac (May, 1965):

There’s hardly anything in the world, or at least in America, more miserable than a transcontinental bus trip with limited means. More than three days and three nights wearing the same clothes, bouncing around into town after town; even at three in the morning, when you’ve finally fallen asleep, there you are being bounced over the railroad tracks of a town, and all the lights are turned on bright to reveal your raggedness and weariness in the seat. To do that, as I’d done so often as a strong young man, is bad enough; but to have to do that when you’re a sixty-two-year-old lady…yet Memère is more cheerful than I, and she devises a terrific trick to keep us in fairly good shape—aspirins with Coke three times a day to calm the nerves.

“The Catskills: Land of Milk and Honey” by Mordecai Richler (July, 1965):

Any account of the Catskill Mountains must begin with Grossinger’s. The G. On either side of the highway out of New York and into Sullivan County, a two-hour drive north, one is assailed by billboards. DO A JERRY LEWIS—COME TO BROWN’S. CHANGE TO THE FLAGLER. I FOUND A HUSBAND AT THE WALDEMERE. THE RALEIGH IS ICIER, NICIER, AND SPICIER. All the Borscht Belt billboards are criss-crossed with lists of attractions, each hotel claiming the ultimate in golf courses, the latest indoor and outdoor pools, and the most tantalizing parade of stars. The countryside between the signs is ordinary, without charm. Bush land and small hills. And then finally one comes to the Grossinger billboard. All it says, sotto voce, is GROSSINGER’S HAS EVERYTHING.

“Bleeker Street: Bohemia’s Barometer” by Michael Herr (December, 1965):

You can choke on your nostalgia. New York changes—even Bleecker, the Village’s quick artery, changes. Five years ago you could feel the presence of ghosts along the street. Nobody ever claimed to have seen them, but you knew they were around. Poe, for one. And Thomas Paine. Maxwell Bodenheim and Joe Gould, inspired panhandlers working opposite sides of the street. Aaron Burr and Edna Millay; Stephen Crane and Doris the Dupe; Wouter Van Twiller, who set the pattern for 300 years of civic corruption; O’Neill and Barrymore and John Reed and Randolph Bourne—that whole Village crowd. Even an occasional brave of the Sappokanikee, who were here first; before the Dutch, the English, the Irish, the Italians; before the suburbanites of the 1800’s, who moved here from lower Manhattan to escape epidemic, or the proto-Bohemians and anarchists of the early 1900’s, or the all-but-vanished Hippies of the late 1940’s; before the precious Adorables of today’s coffeehouse society.

“Shark!” by Peter Benchley (November, 1967):

Irrational behavior has always been man’s reaction to the presence of sharks. Ever since man first returned to the sea, sharks have held all the terror and fascination of an ax murder. To the Greeks they were sea monsters—indeed, the sight of three or four sharks swimming in line, as they sometimes do, with their tails and dorsal fins weaving back and forth, probably started countless tales of mammoth “sea serpents.” Linnaeus declared that Jonah was swallowed by a shark, not a whale. They are the largest fish in the world, growing to almost sixty feet and weighing up to fifteen tons. And today, along with large alligators, crocodiles and an occasional nutty lion or tiger, they are the only animals left on earth that pose a major threat to man. (Not that crocodiles and lions are a real threat; rather they have the size and appetite to be hazardous if a man chooses to stick his foot in one’s mouth.) Very simply, sharks exist in an environment that is still alien to man, and many are decidedly anthropophagous—they eat people.

“Snake Hunter on the Amazon” by Michael Herr (June, 1968):

A hundred miles from Bogota, south of Villavicencio, the plains of Colombia end and the jungles begin, running in unbroken density for more than 600 miles to the Amazon River. Colombia’s eastern border forks, like a snake’s tongue, and meets the river at two points. Leticia, on the southeastern tip, is the fourth largest town along the river, after Belem and Manaus in Brazil, and Iquitos, two hundred miles upriver, in Peru. A few steps out of Leticia will put you near the Brazilian army garrison just over the border, and a few hundred yards across the river, beyond the Colombian gunboat somewhere anchored in the harbor, you can see a Peruvian island. Leticia is the capital of Amazonas, a Colombian territory so remote that it has been called the world’s last true frontier.

“The Canonization of Lenny Bruce” by John Weaver (November, 1968):

Long before the Flower Children began to flock to the holy land of Haight-Ashbury and the Sunset Strip, Lenny had worked the same wilderness, clearing the way for their sexual candor, their drug hangups, their freakouts. He had preached peace and pot, demanded an end to capital punishment, and called on organized religion to stop building new monuments to God’s glory and start feeding His poor.

“Every day people are straying away from the church and going back to God,” he declared, opening an alternate route to salvation for the spiritually dispossessed.

To the young, Lenny is a groovy messiah who drove money-changing hypocrites from suburban temples where they had been salivating at the sight of a new and pretty leg in the choir loft. To their elders, he was a foul-mouthed drug addict who lived by the toilet and, fittingly enough, died by the toilet.

“Conversation with Woody Allen” by Alfred Bester (May, 1969):

“The only thing I find interesting today is sporting events. They have everything that great theater should have; all the thunderous excitement and you don’t know the outcome. And when the outcome happens, you have to believe it because it happened. I need something crammed with excitement. I like things larger than life.”

“A Good Life in the Hollywood Hills” by John Weaver (April, 1970):

Once the rural hideaway of screenwriters and what the city directory called “photoplayers” (Bessie Love lived at 8229 Lookout Mountain), Laurel Canyon now swarms with young rebels and vagrants. The air above its cluttered goat-trails is fragrant with the scent of burning grass and the hills are alive with the sound of Hondas and acid rock. Some of the older canyonites grumble about the longhaired army of occupation, uniformed in love beads, Indian headbands, fringed buckskin jackets and skintight jeans; others are wryly amused by the thought that in their day they were the campus rebels, grappling with coeds in rumble seats and getting high on bathtub gin instead of Acapulco gold.