It’s not that a ’70 BMW 2800 CS Coupe isn’t the most magnificent machine ever designed by man. It is. Or that I wouldn’t orchestrate a major drug deal to own one—or even drive one, just once, along an autumnal Vermont mountain road, en route to a fire-placed inn, with a case of ’85 Canon Saint-Emilion in the trunk, next to a Crouch & Fitzgerald valise stuffed with Thomas Wolfe first editions. I would. These are a few of my favorite things.

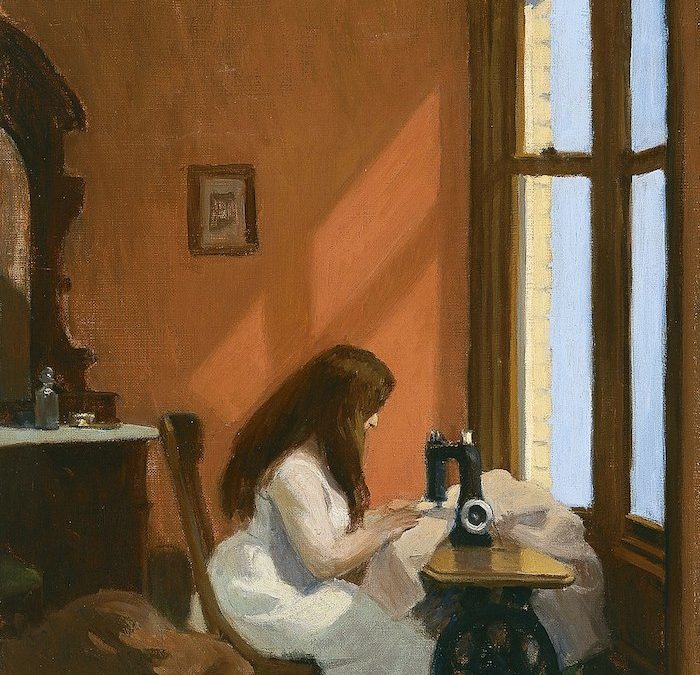

But they do not constitute the good life. I find the good life a little farther off the beaten path, in a world full of unsmiling figures, brooding tenements and shadowy streets—although the sunsets are pretty nice. Edward Hopper could always paint light. Hopper’s light is a corporeal thing, heavy and tangible, illuminating a quiet, unhurried place unbeset by the swarm of the modem species—a place where time has stopped.

My idea of the good life wouldn’t be to own a Hopper; it would be to live in one. Maybe in Gas, with its darkening road to unknown destinations, and its overwhelming sense of stillness in the forest of pines through whose needles wisps a wind making music that cannot be heard in my world. Or High Noon, in which a woman wearing only a bathrobe stands in the front door of a clapboard house. In the fashion of all Hopper’s solitary figures, her mouth is closed; her face is passive and yields no clues. It’s a mask of mystery. Unlike her modern-day counterpart, she feels no need to spill her secrets, to yammer endlessly on daytime television about the bad luck that has befallen her. She is at rest.

This stillness must be what people are trying to find when they spend enormous amounts of money vacationing at remote Caribbean resorts or buy whole islands in the South Pacific. I’ve found it a little closer: In 1978, before a minor-league hockey game, in an art museum in Rochester, New York. In 1992 in an art museum in Cincinnati. In 1973, in a library in Massachusetts, I even held some Hopper etchings. The curator of the collection made me wear gloves, but I felt the calm just the same.

Does my consideration of a Hopper painting feel as good as the night I persuaded my tenth-grade girlfriend to flee her prep school on an interstate bus to meet me in my older brother’s college dorm in Boston, where we fell asleep on the bare wooden floor in front of the fireplace and she slept on her side with her back to me and I awoke to sputtering firelight to find the palm of my right hand resting in the valley of her soft waist between the top of her jeans and the bottom of her ridden-up blue sweater, and it felt as if all of the currents at the heart of the universe were flowing beneath her skin? Does looking at a Hopper feel that good?

My idea of the good life wouldn’t be to own a Hopper; it would be to live in one.

Well, no. But the two have something in common. In the contemplation of both (and that’s more or less what my tryst entailed—contemplation), there is something being stirred and stoked that physical pleasures can’t fuel: the imagination, with its promise of the infinite. Of anything you might want. Just beyond the frame of a Hopper, there’s always something more.

Take the country road in Gas: It’s a road to nowhere in particular, but wherever it’s going, things are probably better there. Or the faceless city in Manhattan Bridge Loop: You’d think it nothing but a cold pile of brick. But I know better. I know that inside the buildings, there is more to be found; there’s the soul of a city. And when I spend time in front of the canvas, I find it.

Or take High Noon. The woman’s bathrobe has fallen open, but shadows demurely cloak her. She is turning her face to the sun. Upstairs, behind waving curtains, her bedroom is dark. There might be someone in it. There might have been someone in it not long ago. There might be someone in it soon. Me, maybe.

You may remain unconvinced. You may find it a preposterous notion that the good life could be made up of windows into a state of mind. You may insist that the good life must comprise the sensory pleasures and the sensual ones. But when your Mondavi Cabernet is drained down to the sediment, your Jag needs new valves and your woman has dismissed you like an empty can of cat food lobbed into the trash, I’ll still have this place where, even if the sun reveals a world that’s haunting and bleak, it’s a sun that never sets.

[Painting via Wikimedia Commons]