Clearly, he comes from good stock.

Interviewed on Canadian television last year, his 87-year-old father was asked, “How do you feel?”

“I feel fine.”

“At what time in life does a man lose his sexual desires?”

“You’ll have to ask somebody older than I am.”

His son was only five when he acquired his first pair of skates. He repeated the third grade, more intent on his wrist shot than on reading, developing it out there in the sub-zero wheat fields, shooting frozen horse buns against the barn door. A mere 14-year-old, working in summer on a Saskatoon construction site with his father’s crew, both his strength and determination were already celebrated. He could pick up 90-pound cement bags in either hand, heaving them easily. Preparing for what he knew lay ahead, he sat at the kitchen table night after night, practicing his autograph.

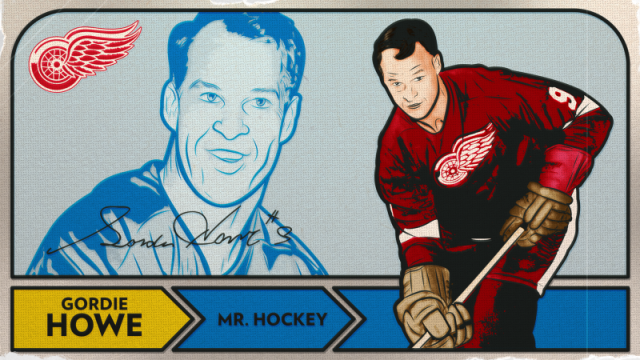

I’m talking about Gordie Howe, born in Floral, Saskatchewan, in 1928, a child of prairie penury, his hockey career spanning 32 active seasons in five decades. The stuff of legend.

Gordie.

For almost as long as I have been a hockey fan, Mr. Elbows has been out there, skating, his stride seemingly effortless. The big guy with the ginger-ale bottle shoulders. To come clean, I didn’t always admire him. But as I grew older and hockey players apparently younger, many of them even younger than my eldest son, he became an especial pleasure to me. Even more, an inspiration. My God, only three years older than me, and still out there, chasing pucks. For middle-aged Canadians, there was hope. In a world of constant and often bewildering change, there was also one shining certitude. Come October, the man for whom time had stopped would be out there, not taking any dirt from anybody. Gordie, Gordie. He became our champion.

Gordie Howe’s amazing career is festooned with records, illuminated by anecdote. Looked at properly, within the third-grade repeater there was a hockey pedagogue longing to leap out.

Item: In 1963, when the traditionally stylish but corner-shy Montreal Canadiens brought up a young behemoth from the minors to police the traffic, he had the audacity to go into a corner with Mr. Elbows. He yanked off his gloves, foolishly threatening to mix it up with Howe.

“In this league, son,” Howe cautioned him, “we don’t really fight. All we do is tug at each other’s sweaters.”

“Certainly, Mr. Howe,” the rookie agreed.

But no sooner did he drop his fists than the old educator creamed him.

Toe Blake, another Canadien who played against Howe, once said, “He was primarily a defensive player when he started, and he’d take your ankles off if you stood in front of the net.”

That was in 1946. Harry Truman was ensconced in the White House. In Ottawa, Prime Minister Mackenzie King, our very own wee Willie, consulted his most trusted advisor nightly—a crystal ball. Everybody was reading Forever Amber. The hot stuff. Bob Feller was back from the war; so were Hank Greenberg and Ted Williams. Jackie Robinson, a black, broke into the lineup of the Montreal Royals. On June 19, Joe Louis knocked out Billy Conn in the eighth round at Yankee Stadium. Eighteen-year-old Gordie Howe, in his first season with the Detroit Red Wings, scored all of seven goals and 15 assists. Thirty-four years later Steve Shutt, who wasn’t even born when Howe was a rookie, reported a different problem in playing against the now silvery-haired legend. “Sure we give him room out there. If you take him into the boards the crowd boos, but they also boo if you let him get around you.”

Which is to say, there were the glory years (more of them than any other athlete in a major sport can count) and the last sad ceremonial season when even the 52-year-old grandfather allowed that he had become poetry in slow motion. But still a fierce advocate for his two hockey-playing sons, Marty and Mark.

“Playing on the same line as your sons,” Maurice Richard once observed, “that’s really something.”

Yes, but when I finally got to interview Howe I asked him if, considering his own legendary abilities, it might have been kinder to encourage his sons to do anything but play hockey.

“Well, once somebody said to Marty, ‘Hey, kid, you’re not as good as your father.’ ‘Who is?’ he replied.”

“When he came flying toward you with the puck on his stick, his eyes were all lit up, flashing and gleaming like a pinball machine. It was terrifying.”

Consider the records, familiar but formidable. Gordie Howe has scored the most assists (1,383) and, of course, played in the most games (2,186). He won the NHL scoring title six times, a record, and was named the most valuable player six times in the NHL and once in the WHA. He has scored more goals than anybody (975-801 in the NHL). His 100th goal, incidentally, was scored on February 17, 1951, against Gerry McNeil of Montreal as the Red Wings beat the Canadiens 2-1 on Maurice Richard Night.

Obloquy.

And a feat charged with significance, because if some of you cut your ideological baby teeth on such trivial questions as whether Stalin was justified in signing a pact with Hitler in 1939, or if FDR threatened the very structure of the republic by running for a precedent-shattering fourth term, or whether Truman needed to drop that bomb on Hiroshima, my Canadian generation came to adolescence fiercely debating who was really numero uno, Gordie Howe or the other No. 9, Maurice “The Rocket” Richard of the Montreal Canadiens.

Out west, where the clapboard main street, adrift in snow, often consisted of no more than a legion hall, a curling club and a Chinese restaurant, the men in their lumberjack jackets—deprived of an NHL team themselves, dependent on radio’s Hockey Night In Canada for the big Saturday night game—rooted for Gordie. One of their own, shoving it to the condescending east. Gordie, who wouldn’t take dirt from anybody, educating the fancy pants frogs with his elbows. Giving them pause, making them throw up snow in the corners.

But in Montreal, elegant Montreal, with its beautiful young women, clean old money and some of the finest restaurants on the continent, we valued élan (that is to say, Richard) above all. For durable Gordie, it appeared the game was a job at which he had undoubtedly learned to excel, but the exploding Rocket, whether he appreciated it or not, was an artist. Moving in over the blue line, he was incomparable. “What I remember most about the Rocket were his eyes,” goalie Glenn Hall once said. “When he came flying toward you with the puck on his stick, his eyes were all lit up, flashing and gleaming like a pinball machine. It was terrifying.”

Seven years older than Howe, Richard played 18 seasons, retiring in 1960. Astonishingly, he never won a scoring championship, coming second to Howe twice and failing two more times by a maddening point. He was voted most valuable player only once. But the one shining record he does hold is a touchstone in the game: Maurice Richard was the first player to score 50 goals in 50 games. That was in 1944-45, in the old six-team league, when anybody scoring 20 goals in a season was considered a star. Toe Blake, once a linemate of the Rocket and a partisan to this day, maintains, “There’s only one thing that counts in this game and that’s the Stanley Cup. How many did Jack Adams win with Gordie and how many did we take with the Rocket?”

The answer to that one is Detroit took four Cups with Gordie and the Canadiens won eight propelled by the Rocket. However, Richard’s supporting cast included, at one time or another, Elmer Lach, Blake, Richard’s brother Henri, Jean Beliveau, Boom Boom Geoffrion, Dickie Moore, Doug Harvey, Butch Bouchard and Jacques Plante. Howe had Sid Abel and Terrible Ted Lindsay playing alongside him and there also was Alex Delvecchio. He was backed up by Red Kelly on defense, either Glenn Hall or Terry Sawchuk in the nets and, for the rest, mostly a number of journeymen. Even so, the Red Wings, led by Gordie Howe, finished first in regular-season play seven times in a row, from 1949 to 1955. They beat the Canadiens in the 1954 Stanley Cup final and again in 1955, although that year the issue was clouded, a seething Richard having been suspended for the series.

“Gordie Howe is the best hockey player I have ever seen,” Beliveau has said. Even Maurice Richard allows, “He was a better all-around player than I was.”

Yes, certainly, but there’s a kicker. A big one.

The Rocket’s younger brother, former Canadien center Henri Richard, has said, “There is no doubt that Gordie was better than Maurice. But build two rinks across from one another. Then put Gordie in one and Maurice in the other, and see which one would be filled.”

Unlike the Rocket, Bobby Hull, Bobby Orr and Guy Lafleur, Howe always lacked one dimension. He couldn’t lift fans out of their seats, hearts thumping, charged with expectation, merely by taking a pass and streaking down the ice. The most capable all-around player the game may ever have known was possibly deficient in only one thing—star quality. But my, oh my, he certainly could get things done. In the one-time rivalry between Detroit and Montreal, two games linger in the mind, but first a few words from Mr. Elbows himself on just how bright that rivalry burned during those halcyon years.

“Hockey’s different today, isn’t it? The animosity is gone. I mean we didn’t play golf with referees and linesmen. Why, in the old days with the Red Wings, I remember once we and the Canadiens were traveling to a game in Detroit on the same train. We were starving, but their car was between ours and the diner, and there was no way we were going to walk through there. We waited until the train stopped in London [Ontario] and we walked around the Canadiens’ car to eat.”

The most capable all-around player the game may ever have known was possibly deficient in only one thing—star quality.

Going into a game in Detroit, against the Canadiens, on October 27, 1963, Howe had 543 goals, one short of the retired Rocket’s then record total of 544. The aroused Canadiens, determined not to allow Howe to score a landmark goal against them, designated Henri Richard his brother’s record keeper, setting his line against Howe’s again and again. But in the third period Howe, who had failed to score in three previous games, made his second shot of the night a good one. He deflected a goalmouth pass past Gump Worsley to tie the record. Howe, then 35, did not score again for two weeks and, lo and behold, the Canadiens came to town once more. And again they put everything into stopping Howe. But, in the second period, with Montreal on the power play, Detroit’s Billy McNeill sailed down the ice with the puck, Howe trailing. As they swept in on the Canadien net, Howe took the puck and flipped a 15-foot shot past Charlie Hodge, breaking the Rocket’s record, one he was to improve on by 257 NHL goals.

Item: In 1960, there was a reporter sufficiently brash to ask Howe when he planned to retire. Blinking, as is his habit, he replied, “I don’t want to retire, because you stay retired for an awfully long time.”

Twenty years later, on June 4, 1980, Howe stepped up to the podium at the Hartford Hilton and reluctantly announced his retirement. “I think I have another half-year in me, but it’s always nice to keep something in reserve.” The one record he was terribly proud of, he added, “is the longevity record.”

Thirty-two years.

And possibly, just possibly, we were unfair to him for most of those years. True, he’s now an institution. Certainly, he won all the glittering prizes. And for years he was recognized wherever he went in Canada. But true veneration always eluded Howe. Even in his glory days he generated more respect, sometimes even grudging at that, than real excitement. Outside of the west, where he ruled supreme, he was generally regarded as the ultimate pro (say, like his good friend of the Detroit years, AI Kaline), but not a player possessed. Like the Rocket.

In good writing, Hemingway once ventured, only the tip of the iceberg shows. Put another way, authentic art doesn’t advertise. Possibly, that was the trouble with Gordie on ice. During his vintage years, you seldom noticed the flash of elbows, only the debris they left behind. He never seemed that fast, but somehow he got there first. He didn’t wind up to shoot, like so many of today’s golfers, but next time the goalie dared to peek, the puck was behind him.

With hindsight, I’m prepared to allow that Gordie may not only have been a better player than the Rocket, but maybe the more complete artist as well. The problem could have been the fans, myself included, who not only wanted art to be done, but wanted to see it being done. We also required it to look hard, not just all in a day’s work.

A career of such magnitude as Gordie Howe’s has certain natural perimeters, obligatory tales that demand to be repeated here. The signing. The injury that all but killed him in his fourth season. The rivalry with the Rocket, already dealt with. The disenchantment with Detroit. Born again Gordie, playing in the WHA with two of his sons. The return to the NHL with the Hartford Whalers. The last ceremonial season, culminating in the great one’s final goal.

History is riddled with might-have-beens. Caesar, anticipating unfavorable winds, could have remained in bed on the 15th of March. That most disgruntled of stringers, Karl Marx, might have gone from contributor to editor of the New York Tribune. Bobby Thomson could have struck out. Similarly, Gordie Howe might have been a New York Ranger. When he was 15, he was invited to the Rangers’ tryout camp in Winnipeg, but they wanted to ship him to Regina, and he didn’t sign because he knew nobody from Saskatoon would be playing there. The Red Wings asked him to join their team in Windsor, Ontario. “They told me there would be a carload of kids I knew, so I signed. I didn’t want to be alone.”

The following season, the Red Wings handed Gordie a $500 bonus and a $1,700 salary to play with their Omaha farm club. (“Twenty-two hundred dollars,” Gordie says. “I earn that much per diem now.”) A year later he was with the Red Wings, signed for a starting salary of $6,000. “After we signed him,” coach Jack Adams said, “he left the office. Later, when I went into the hall, he was still there, looking glum. ‘All right, Gordie, what’s bothering you?’

“‘Well, you promised me a Red Wing jacket, but I don’t have it yet.’”

He got the jacket, he scored a goal in his first game with the Wings, and he was soon playing three, even four-minute shifts on right wing. A fast, effortless skater with a wrist shot said to travel at 110 miles per hour. Then, in a 1950 playoff game with the Toronto Maple Leafs, Howe collided with Leaf captain Teeder Kennedy and fell unconscious to the ice. Howe was rushed to a hospital for emergency surgery. “In the hospital,” Sid Abel recalled, “they opened up Gordie’s skull to relieve the pressure on his brain and the blood shot to the ceiling like a geyser.”

The injury left Howe with a permanent facial tic, and on his return the following season, his teammates dubbed him “Blinky,” a nickname that stuck. Other injuries, over the years, have called for some 400 stitches, mostly in his face. Howe can no longer count how many times his nose has been broken. There also have been broken ribs, a broken wrist, a detached retina and operations on both knees. He retires with seven fewer teeth than he started with.

The glory years with Detroit came to an end in 1971, Howe hanging up his skates after 25 seasons. Once a contender, the team had gone sour. Howe’s arthritic wrist meant that he was playing in constant pain. Hockey, he allowed, was no longer fun. But, alas, the position he took in the Red Wings’ front office (“A pasture job,” his wife Colleen said) proved frustrating, even though it was his first $100,000 job. “They paid me to sit in that office, but they didn’t give me anything to do.”

Then, after two years of retirement, the now 45-year-old Howe bounced back. In 1973, he found true happiness, realizing what he said was a lifelong dream, a chance to play with two of his sons for something called the Houston Aeros of the WHA. The dream was sweetened by a $1-million contract, which called for Howe to play for one season followed by three in management. Furthermore, 19-year-old Marty and 18-year-old Mark were signed for a reputed $400,000 each for four years. A package put together by the formidable Colleen, business manager of the Howe family enterprises.

Howe led the Aeros to the WHA championship; he scored 100 points and was named the league’s most valuable player. Mark was voted rookie of the year. A third son, Murray, later shunned hockey to enter pre-med school at the University of Michigan. Murray, now 20, also writes:

So you eat, and you sleep.

So you walk, and you run.

So you touch, and you hear.

You lead, and you follow.

You mate with the chosen.

But do you live?

Gordie went on to play three more seasons with the Aeros and two with the Whalers, finishing his WHA career with 174 goals and 334 assists. With the demise of that league and the acceptance of the Whalers by the NHL in 1979, Howe decided to play one more year so that the father-and-sons combination could make it into the NHL record books.

It almost didn’t happen, what with Marty being sent down to Springfield. But they finally did play together March 9 in Boston. And then three nights later, out there in Detroit, his Detroit, Gordie finally got to take a shift in the NHL on a line with his two sons, Marty moving up from his natural position on defense. “After that game Gordie could have just walked off,” Colleen said. “‘I’ve done all I ever wanted,’ he told me.”

I caught up with Gordie toward the end of the season, on March 22, when the Whalers came to the Montreal Forum for their last regular-season appearance. Before the game, Gordie Howe jokes abounded among the younger writers in the press box. Scanning the Hartford lineup, noting the presence of Bobby Hull and Dave Keon, both in their 40s, one wag ventured, “If only they put them together on the ice with Howe, we could call it the Geritol Line.”

“When is he going to stop embarrassing himself out there and announce his retirement?”

“If he’s that bad,” a Hartford writer cut in, “why do they allow him so much room out there?”

“Because nobody wants to go into the record books as the kid who crippled old Gordie.”

Going into the game, Hartford’s 72nd of the season, Howe had 14 goals and 23 assists, and there he sat on the bench, blinking away, one of only six Whalers without a helmet. The only one on the bench old enough to remember an NHL wherein salaries were so meager that the goys of winter had to drive beer trucks or work on road construction in the summer.

There were lots of empty seats in the Forum. It was not the usual Saturday night crowd. Many a season ticket holder had yielded his coveted place in the reds to a country cousin, a secretary or an unlucky nephew. Kids were everywhere. Howe, who had scored his 800th NHL goal a long 23 days earlier, jumped over the board for his first shift at 1:27 of the first period, the Forum erupting in sentimental cheers. He did not come on again for another five minutes, this time joining a Hartford power play. Howe took to the ice again with 4½ minutes left in the period, kicking the puck to Jordy Douglas from behind the Montreal net, earning an assist on Douglas’ goal. Not the only listless forward out there, often trailing the play, pacing himself, but his passing still notably crisp, right on target each time, Howe came out six more times in the second period. On his very first shift in the third period, he threw a check at Rejean Houle, sending him flying. Hello, hello, I’m still here. But his second time out, Howe drew a tripping penalty, and the Canadiens scored on their power play. The game, a clinker, ended in a 5-5 tie.

In the locker room, microphones were thrust at a weary Gordie. He was confronted by notebooks. Somebody asked, “Do you plan to retire at the end of the season, Gordie?”

“Not that f—— question again,” Gordie replied.

So somebody else said, “No, certainly not. But could you tell me what your plans are for next year?”

Gordie grinned, appreciative.

A little more than two weeks later, on April 8, the Whalers were back, it having been ordained that these upstarts would be fed to the Canadiens in their first NHL playoff series. This time the Canadiens, in no mood to fiddle, beat the Whalers 6–1. Howe, who didn’t play until the first period was seven minutes old, took his first shift alongside his son Mark. He only appeared twice more in the first period, but in the second he came on again, filling in for the injured Blaine Stoughton on the Whalers’ big line. He was, alas, ineffectual, on for two goals against and hardly touching the puck during a Hartford power play. Consequently, in the third period, he was allowed but four brief shifts. There must have been some satisfaction for him, however, in the fact that Mark Howe was easily the best Whaler on ice, scoring the goal that cost Denis Herron his shutout.

“You can’t be a pauper living out here,” the driver said. “I’ll bet he’s got race horses and everything. There’s only money out here.”

The next night, with Montreal leading 8–3 midway in the third period, the only thing the crowd was still waiting for finally happened. Gordie Howe flipped in a backhander. It was his 68th NHL playoff goal—but his first in a decade. It wasn’t a pretty goal. Neither did it matter much. But it was slipped in there by a 52-year-old grandfather who had scored his first NHL goal in Toronto 34 years earlier when Carl Yastrzemski was seven years old, pot was something you cooked the stew in and Ronald Reagan was just another actor with pretensions. (For the record, that first goal was scored against Turk Broda on October 16, 1946.) “Hartford goal by Gordie Howe,” Michel Lacroix announced over the P.A. system. “Assist, Mark Howe.” The crowd gave Gordie a standing ovation.

Later, in the Whalers’ dressing room, coach Don Blackburn was asked what his team might do differently in Hartford for the third game. “Show up,” he said.

Though the Whalers played their best hockey of the series, they lost in the 29th second of overtime, Yvon Lambert banging in the winning goal for Montreal. In the locker room, everybody wanted to know if this had been Gordie’s last game. “I haven’t made up my mind about when I’m going to retire yet,” he said.

But earlier, in the press box, a Hartford reporter had assured everybody that this was a night in hockey history. April 11, 1980. Gordie Howe’s last game. Whaler director of hockey operations Jack Kelley had told him. “They’ve got a kid they want to bring up. Gordie’s holding him back. The problem is they don’t know what to do with him. I mean, shit, you can’t have Gordie Howe running the goddamn gift shop.”

The triumphant Canadiens stayed overnight in Hartford, and I joined their poker game. Claude Mouton, Claude Ruel, the trainers, the team doctor, Floyd “Busher” Currie, Toe Blake. “Jack Adams always used him too much during the regular season,” Toe said, “so he had nothing left when the playoffs came round.”

“Do you think he was really a dirtier player than most?” I asked.

“Well, you saw the big man yesterday. What did he tell you?”

“He said his elbows had never put anybody in the hospital, but he was there five times.”

Suddenly, everybody was laughing at me. Speak to Donnie Marshall, they said. Or John Ferguson. Still better, ask Lou Fontinato.

When Donnie Marshall was with the Rangers, he was asked what it was like to play against Howe. In reply, he lifted his shirt to reveal a foot-long angry welt across his rib cage. “Second period,” he said.

One night, when Winnipeg Jet general manager John Ferguson was playing with the Canadiens, a frustrated Howe stuck the blade of his stick into his mouth and hooked his tongue for nine stitches.

But Howe’s most notorious altercation was with Ranger defenseman Lou Fontinato in Madison Square Garden in 1959. Frank Udvari, who was the referee, recalled, “The puck had gone into the corner. Howe had collided with Eddie Shack behind the net and lost his balance. He was just getting to his feet when here’s Fontinato at my elbow, trying to get at him.

“‘I want him,’ he said.

“‘Leave him alone, use your head,’ I said.

“‘I want him.’

“‘Be my guest.’”

“They ought to bottle Gordie Howe’s sweat,” King Clancy of the Maple Leafs once said. “It would make a great liniment to rub on hockey players.”

Fontinato charged. Shedding his gloves, Howe seized Fontinato’s jersey at the neck and drove his right fist into his face. “Never in my life had I heard anything like it, except maybe the sound of someone chopping wood,” Udvari said. “THWACK! And all of a sudden Louie’s breathing out of his cheekbone.”

Howe broke Fontinato’s nose, he fractured his cheekbone and knocked out several teeth. Plastic surgeons had to reconstruct his face.

The afternoon before what was to be Howe’s last game, I took a taxi to his house in the suburbs of Hartford. “You can’t be a pauper living out here,” the driver said. “I’ll bet he’s got race horses and everything. There’s only money out here.”

Appropriately enough, the venerable Howe, hockey’s very own King Arthur, lives down a secluded side road in a town called Glastonbury. Outside the large house, set on 15 acres of land, a sign reads HOWE’S CORNER. Inside, a secretary ushered me through the office of Howe Enterprises, a burgeoning concern that holds personal-service contracts with Anheuser-Busch, Chrysler and Colonial Bank. A bespectacled, wary Howe was waiting for me in the sun-filled living room. Prominently displayed on the coffee table was an enormous volume of Ben Shahn reproductions.

“I had no idea,” I said, “that you were an admirer of Ben Shahn.”

“Oh, that. The book. I spoke at a dinner. They presented it to me.”

After all his years in the United States, Howe remains a Canadian citizen. “I can pay taxes here and all the other good things, but I can’t vote.” One of nine children, he added, the family is now spread out like manure. “It would be nice to get together again without having to go to another funeral.”

Sitting with Howe, our dialogue stilted, not really getting anywhere, I remembered how one of the greatest journalists of our time, A. J. Liebling, was once sent a batch of how-to-write books for review by a literary editor, and promptly bounced them back with a curt note: “The only way to write is well and how you do it is your own damn business.” Without being able to put it so succinctly, Howe, possibly, felt the same way about hockey. Furthermore, over the years he had also heard all the questions before and now greeted them with a neat flick of the conversational elbow. So we didn’t get far. But, for the record, Howe said that, in his opinion, today’s hockey talent is bigger and better than ever. Wayne Gretzky reminds him of Sid Abel. “He’s sneaky clever, the puck always seems to be coming back to him. Lafleur is something else. He stays on for two shifts. I don’t mind that, but he doesn’t even breathe heavy.” Sawchuk was the best goalie he ever saw and he never knew a line to compare with Boston’s Kraut Line: Milt Schmidt, Woody Dumart, Bobby Bauer. Howe is still bitter about how his years in Detroit came to an end with that meaningless front-office job. “Hell, you’ve been on the ice for 25 years, there’s little else you learn. I was a pro at 17. Colleen used to answer my fan mail for me, I didn’t have the words. Now it’s better for the kids. They get their basic 12 years of school and then pick a college.”

Trying to surface with a fresh question, I asked him when he planned to retire.

“I can’t say just yet exactly when I’m going to retire, but I’m the one who will make that decision.”

But the next morning, in the Whaler offices, Jack Kelley asked me, “Did he say that?”

“Yes.”

Kelley ruminated. “When’s your deadline?”

“Not until the autumn.”

“He’s retiring at the end of the season.”

Almost two months later, on June 4, Howe made it official. “It’s not easy to retire,” he told reporters in Hartford. “No one teaches you how. I found that out when I tried it the first time. I’m not a quitter. But I will now quit the game of hockey.”

Howe had kept everybody waiting for half an hour after the scheduled start of his 10 a.m. press conference. “As it got close to 10:30, I had the funny suspicion that he had changed his mind again,” Kelley said.

But this time Howe left no doubt in anybody’s mind. “My last retirement was an unhappy one, because I knew I still had some years in me. This is a happy one, because I know it’s time.”

This winter, then, Gordie is not going to be out there, skating. He will be the Whalers’ director of player development. His No. 9 has joined Maurice Richard’s No. 9 in retirement. An ice age has come to an end.

“They ought to bottle Gordie Howe’s sweat,” King Clancy of the Maple Leafs once said. “It would make a great liniment to rub on hockey players.”

Yes. Certainly. But I remember my afternoon at Howe’s Comer with a certain sadness. He knew what was coming, and before I left he insisted that I scan the awards mounted on a hall wall. The Victors Award. The American Academy of Achievement Golden Plate Award. The American Captain of Achievement Award. “I played in all 80 games this year and I got my 15th goal in the last game of the season. Last year I suffered from dizzy spells. My doctor wanted me to quit. But I was determined to play with my boys in the NHL. I don’t think I have the temperament for coaching. I tried it a couple of times and I got so excited, watching the play, I forgot all about line changes.”

But that afternoon only one thing really seemed to animate him. The large Amway flow chart that hung from a stand, dominating the living room. Gordie Howe—one of the greatest players the game has ever known, a Canadian institution at last—Blinky, the third-grade repeater who became a millionaire—today distributes health care, cosmetics, jewelry and gardening materials for Amway.

Offering me a lift back to my hotel in Hartford, Howe led me into his garage. There were cartons, cartons, everywhere, ready for delivery. Cosmetics. Gardening materials. It looked like the back room of a prairie general store.

“I understand you write novels,” he said.

“Yes.”

“There must be a very good market for them. You see them on racks in all the supermarkets now.”

“Right. Tell me, Gordie, do you deliver this stuff yourself?”

“You can earn a lot of money with Amway,” he said, “working out of your own home.”

Say it ain’t so, Gordie.

[Featured Image: Sam Woolley/GMG]