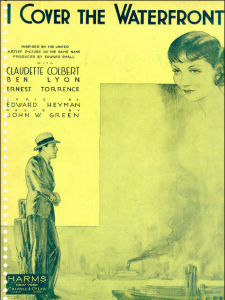

Joyce Wadler got her start at the old New York Post, later wrote for The Washington Post, and was at the New York Times for many years. When she was at the Times would give young reporters Max Miller’s terse and charming 1932 book, I Cover the Waterfront. They made a movie out of Miller’s book staring Claudette Colbert in ’33 and also a song, which became a jazz standard. Miller’s book is sharp in detail, his prose clean and unpretentious as you can see in these three excerpted chapters. Enjoy.—AB

One

He is a cripple, and he moves about the waterfront on a contraption of three wheels. They are too low to be off a bicycle, and the framework is like a skeleton, a skeleton of a vehicle long dead.

The way I happen to know how he makes his living is because I was downstairs in the tugboat office when he wheeled himself to the doorway.

“Hello,” Clarke Andrews said to him.

“Hello,” the cripple answered. “I brought these new ones you wanted to see.”

“Let’s see them, then. Hey, you fellows, come see them. They’re good.”

The cripple brought out a booklet from inside his shirt. He began turning the pages. The characters were plagiarisms from comic strips. The characters were all drawings of comic-strip people undressed.

“How much?” Clarke Andrews asked.

“A dollar’n half.”

“Pretty much but keep on turning.”

“If I keep on turning you’ll not want to buy it. They get better later on.”

“Keep on turning. We’ll buy it all right, won’t we, fellows? We’ll buy it all right.”

“You said you’d buy the photographs and you didn’t.”

“But you asked too damned much for them. Besides they weren’t much good. They were blurred.”

“But you said you’d buy them and you didn’t. You looked at them but you didn’t buy them.”

“We’ll buy this all right. These are good. These are rich. Keep on turning.”

The cripple turned the pages. He turned them slowly, so the men could read the words in the balloons. Perhaps this was the way the cripple had of getting back at men who were not cripples, perhaps this was the way he had of laughing at them by showing them pictures of themselves. Or perhaps again he simply wanted to make a living in the only way he knew. I don’t know. I cannot even guess. All I can say is that when he got through showing the booklet he turned to Andrews and held it out for him to take.

But Andrews didn’t take it. He said, “Hell, that ain’t got half the kick in it you said it had. Hell, a guy can get pictures almost as good as that right in them magazines. Hell.”

The cripple bit his lips but said nothing. Besides, the law, too, was against him. He backed his contraption from the doorway. He swung the wheels around and started to go.

“Here, I’ll buy it,” Olaf Smith said. Olaf is one of the shoreboat operators. He works for Andrews. “Here’s the dollar’n half.”

The cripple held out the booklet and Olaf took it. The cripple wheeled away then, leaving Olaf standing there with the naked purchase in his hand.

Olaf came back to Andrews and handed the booklet to him. “Here, Andrews. Take it home and show it to your kids. I’ve always wanted to give you a present, anyway. You’ve got it coming. You’re such a swell fellow.”

Two

Today I had to deliver a message to a young sailor aboard a destroyer anchored in the harbor. I had to inform him of what perhaps is the deepest news to a man, and I was conscious the while of a primitive curiosity of how he would weather the information.

Our office had received a wire story from Portland that the man’s wife had attempted to kill herself and had succeeded in chloroforming to death her two children.

This, I knew, was the acme of all bad news. In my time I have delivered many verbal messages of death to wives and to husbands. But now I positively had the very worst, and I still wonder why I was not more ashamed of my own personal curiosity.

In sending me out to the vessel, the office, of course, was not being philanthropic. The wire service out of Portland wanted an interview with the sailor, wanted a story on him, wanted to know if he could explain any motive for the double crime. My own paper wanted the story, too. Being the waterfront reporter, I merely was the agent. For I did not know the man.

My shoreboat let me off at the gangway, and I asked the officer of the deck if I could see the sailor.

“A hell of a thing’s happened to his family,” I said. “And I have to tell him.”

“Sure, if it’s real important.”

“It is.”

The officer of the deck summoned an orderly, and the orderly went in search of the sailor, and in time the sailor arrived from below, smiling. From the helm and chevrons on his sleeve I could tell he was a quartermaster first-class, and I felt like God standing there with the power to crunch him. I was a giant with a fly-swatter. For all of his smile he could not get away from me. He was cornered.

The grief on my face was not all natural. Some of it was placed there professionally for the sake of the interview I should obtain from him without his really knowing. And from that moment on I was aware of having been in newspaper work a day too long. I, too, was gone the same as the desk men were gone, the desk men who had sent me out here.

“Does your family live in Portland?” I asked, to make sure.

“Yes.”

“And have you two children?” I gave their names.

“Yes.”

“Then come over here.” I guided the way to the ship’s railing. There we could lean and look down into the water. The bay would be our only audience. And all the time I was acting. I was breaking the news after the formula of the stage. I did not comprehend how I could be so indifferent, or how I could be thinking of my story as much as of him. I was preparing my interview ahead of time, and my face by now must be the face of a hard man. It must be hard, for I am hard. The test came and found me hard.

“Your wife attempted suicide.”

He glanced quickly towards me, as if to catch me delivering a practical joke, almost as if to see if I would break into a laugh. But the reportorial actor in me continued to register sorrow. Convincing sorrow, too, perhaps. For immediately he depended on me for more information, and feeling this dependence I permitted my information to linger awhile. He would have demanded more outright, but I beat him to the words!

“But she’s all right now. She didn’t get by with it. But before trying to kill herself, she did—”

Now for the fly-swatter. Now for the execution. Was my prisoner ready? Was he in the proper suspense. Yes, he was ready. He was waiting. Very well, then let him have it. And watch his expression too. And catch each little word he may say. You’ll need it, waterfront reporter. You’ll need it to write for the desk men. And they’ll need it for Portland. You’re on a job, don’t forget. The shoreboat to send you out here cost money, good money. Let him have it. Let the young man have it now.

“But before trying to kill herself, she did—” And I came down with the swatter. And back in the office my story made the front page, my story carried a head reserved for human-interest stories, and the managing editor said the story “showed the good old stuff.” I know, because he commented on the story in staff meeting. He said the story got down under the surface and had “all the good old sympathy guts to it that I want to see more of around here.”

Three

For washing the city off one’s skin at the end of a day’s work, nothing around here of course quite equals a fast dive into the surf when few people are present on the beach. Many are present at noon, but not at the end of the day, for the summer visitors usually prefer their dips when the sun is at its highest pitch for tanning the Eastern shoulders.

My favorite cove, then, usually is rather deserted near supper-time, and I can dive for all I like without the danger of seeming to be showing off.

The rollers come in regularly, are hushed a bit by a reef, and can be timed to one’s liking. Each seventh roller usually is the largest. It puffs out its blue chest in defiance to its enemy, the beach, which so soon will put an end to all such gallantry.

The roller comes on, begins to show a white curl along the top as though showing its teeth at the sand, and then is the time to strike, and to strike straight for the stomach of the brute.

By opening one’s eyes, then, the under-water world is such a contrast to the upper world that all of the day’s ridiculous transactions are instantly slashed off the register of one’s brain. A few rocks are down there, to be sure, but they are more like under-water benches, and they are upholstered with waving seagrass. And from under the legs of these benches the golden Garibaldi perch poke their surprised heads out to see what is happening, or has happened, and so odd is all this new room to the world-house that one for a time does not really miss the inability to breathe.

But late in the afternoon recently my cove has been having a group of visitors, the same visitors now for five successive evenings. Two women are in the group and two men. And one of the men, the one who appears about my own age, has been doing his swimming almost constantly in the one clear spot for diving. He stays there, swimming about on his back, sometimes floating, sometimes paddling, but always in the way. He seldom leaves the shoreline more than a few yards, and I have to wait for him. He does not dive under the water, nor does he seem much interested in what is down there, the greens and yellows, the abalone shells, and the few Garibaldi.

Frequently I have been tempted to dive in close to him, or under him, just to teach him a few manners. And once when we were both out there and I was trying to get by him for deeper water he swam right into me from a crazy angle.

“Pardon me,” he said, and continued paddling on his back. But I was too annoyed at his awkwardness to answer civilly. I mumbled something and swam on.

Later, about twenty minutes later, when I returned to the sand to go home, the other people were getting ready to go home, too. And I watched them climb the trail leading up the cliff. They were guiding the young man along, the man who was about my own age. For, his eyes being open and as clear as my own, I had not known he was blind, completely blind. And when I open my eyes under water now, and see the room of retreat down there, I feel kind of funny. I feel kind of funny and shaky all over.

[Excerpt courtesy of Skyhorse Publishing; Featured Image: Irma and Paul Milstein Division of United States History, Local History and Genealogy, The New York Public Library. “La Jolla rocks” The New York Public Library Digital Collections]