At three in the morning, coming east across the Bay Bridge in a limousine the size of a cattle truck, a quiet falls over the back seat. It is the last day before John Matuszak goes to Santa Rosa for training camp. More to the point, it is Wednesday. There are three of us in the back—John and me and Donna, the girl he cares for above all others—and suddenly, as if by unspoken agreement, it is time for some quiet thinking and assessment.

We have run out of flaming arrows—matches, Southern Comfort, shot glasses. “Jeez, that’s too bad,” the driver says. He doesn’t sound like it’s too bad.

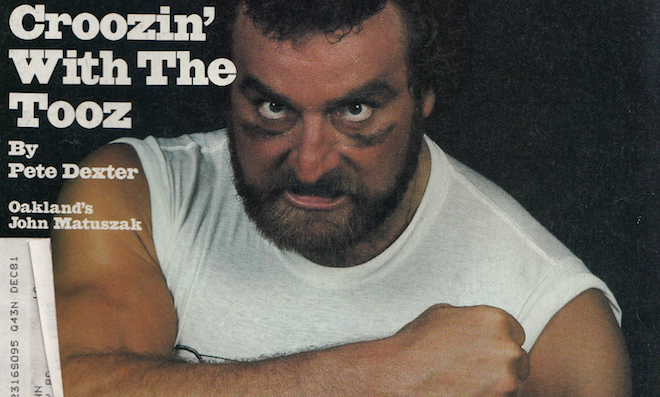

I’m not the first person to wonder what John Matuszak was thinking. Since he came into the National Football League as the first draft pick of 1973—ahead of people like Bert Jones and John Hannah—that question has been on a lot of minds at one time or another.

Matuszak went to Houston in that draft, then to the World Football League, where he played one series of downs before he was handed an injunction returning him to the NFL, then to Kansas City. He was traded from there to Washington where George Allen, whose idea of temptation is a quart of ice cream, cut him in two weeks. Matuszak was on the way to the Canadian Football League when Al Davis flew out from Oakland and offered him a chance to play for the Raiders in 1976.

He has been there since. “It’s the only place I could play,” he said once. “I know my reputation around the league.” The reputation, briefly, is that he still belongs in the straitjacket they used on him when he overdosed on depressants and alcohol in Kansas City.

The truth, though, unless you happen to look at it from a very tight-ass point of view, say, that of most of the coaches in the National Football League, is that while Matuszak has had his share of scrapes, most of them can be put down to growing pains. That and things found hidden in his automobiles. A machete, a .44 magnum, a little dope.

Anyway, all that was before he mellowed….

MILWAUKEE

Sometimes you go in and it’s like you’re Edward R. Murrow. You let go of the doorbell and hear the footsteps. You feel it coming and there’s no place to hide.

The kids are going to be lined up on the couch, youngest to oldest. The little girls will have ribbons in their hair, Skipper the mongrel will be there on the floor and mom will be sitting at the end with an arm around Dale Jr. Trophies over the fireplace and dad is out in the shop, finishing up some woodwork. Why don’t we go see how he’s doing?

You wait at the door, dead certain that unless a sociable way to pass a quart of 151 up and down that couch presents itself, you’re doomed.

But the door opens and it’s Audrey Matuszak, still in the skirt she’d worn to work, talking on the phone. Somebody she has never heard of in New York wants to know if she’s big.

She holds the door while I come in. “Big?” she says. “Why, I never thought of it. I’m 6-5 and 265 … no, that’s about average in the family….” Some days you’re doomed, some days you’re not.

She says the sweetest goodbye you ever heard and cradles the phone against her ear a minute longer. “I shouldn’t have done that, I suppose,” she says, “but sometimes you wonder about New York, don’t you?”

“Yes ma’am, you do.” She smiles and gets me a beer out of the refrigerator. There is an autographed picture of her son on the door. BEST WISHES TO MOM AND DAD, YOU’RE THE GREATEST. JOHN. It is the only evidence on the main floor of the house that he is different from the other children. The trophies, the movie posters are upstairs in the bedrooms.

“I think you’re going to enjoy John,” she says. “He’s just so much fun to be with. He’s out in back if you want to see what’s he’s doing.”

Picture old Ed now, sitting back in a cloud of Lucky Strike smoke, watching the camera roll through the doorway to the backyard where John Matuszak, massive and naked except for bikini swimwear, is sitting on an old blanket, tearing the big toenail off his right foot. He holds it up to the sun, checking both sides.

He looks at the nail, then at the toe. “Toes are tender,” he says.

I take a look at the toenail, then give it back. “That looks like it was a real nice one.”

He nods. “It’s been getting on my nerves, though.”

Matuszak puts the nail next to him on the blanket and leans back to find a new station on the portable radio. “I’ve been on a hot streak,” he says. “It’s hard to explain. I was driving into town Wednesday and suddenly I said ‘Blue Suede Shoes,’ and half a minute later that’s what they played. The same thing happened with ‘Déjà Vu.’ Yeah, that’s a song. You know what I mean, when you’re just tuned with things?”

I think that over. “I always know it just before a dog bites me.”

At the work “dog,” he looks around to make sure his mother is gone. He lowers his voice and points to a pile of freshly turned dirt over by the garden. “They just buried Skipper,” he says. “It really broke them up, they’d had him for years.”

I swear. Skipper. A hot streak of my own. The radio cracks and suddenly Brenda Lee is singing “All Alone Am I.” Matuszak closes his eyes and runs a hand through his hair. “Look at me,” he says, pointing to his arm and shoulder. “Goose bumps. Brenda Lee, 1962. That’s what music does to me. I couldn’t live without music.”

He sings along with Brenda. He tests the toe. He reasons with it. “Well, there’s always a hump out there you’ve got to get over, right?”

The hump is an asphalt hill on the other side of the two-lane highway that runs in front of his parents’ house. The hill angles like a swan’s beak about a quarter of a mile down, then flattens into a dirt road and disappears into a railroad tunnel. The radio has just said it is three o’clock and 105 degrees at Gen. Billy Mitchell airport. The heat off the asphalt makes the tunnel seem to float.

The Tooz is wearing sweat pants now, two plastic jackets, a towel around his neck and a wool stocking cap with the insignia of the Oakland Raiders pulled down over his ears.

“Just sit over there on the fence, stud, and I’ll be right back.” He jogs down the hill, getting smaller and smaller, his body waving in the heat until, at the bottom, he could almost be of this earth. He comes back up, spitting and pounding, growing like a bad dream.

At the top he walks it off, blowing his nose.

He will run the hill three more times before he quits, each time coming up harder than the time before. He is big, even for a pro football player—6-8, 300 pounds and none of it is fat—but you don’t really feel it until you see him tired, and he can feel it, too. Walking back to the house he says, “Well, I kicked the hill’s ass today.”

It is the Fourth of July, so the gym is closed and there is no place to lift weights. Matuszak likes to lift weights. He began when he was 11—other children were making fun of him for being awkward—and it is 19 years later. Sometimes when he’s had a couple of drinks, you see him listening to make sure nobody is doing that now. He lies back down on the blanket and closes his eyes against the sun. “This is a day to be on the beach,” he says. “You know, get your hair just right and walk up and down. See and be seen.

“I’m the kind of guy who’s all or nothing. I mean, if I’m going to go out and get screwed up, I do it all the way. If I’m not, I’m not. People keep telling me I’ve got to change my image. They never say how. Even my friends. Dave Pear said that. I don’t know what that means. I do know that things get distorted. Like, they wrote a story that said I’d torn the plumbing out of the walls at this bar. All that was, me and Pear were playing around in the bathroom and we knocked down the door. It wasn’t even much of a door, and here everybody’s saying I ripped the plumbing out.

“It’s the same thing with the fights. I’m 30 years old, and I’ve been in five fights in my life. The one down in Florida, I was wrong. I hurt somebody and I had to pay for it. I’m sorry it happened. [As a senior at Tampa, Matuszak hit another football player—a flanker—with his elbow during a game of basketball and broke most of the bones on one side of his face.]

“Of course, he didn’t come looking for money until I was drafted first, and he had taken my legs out from under me while I was going up for a shot, and the amount of money I had to pay him [$65,000] was worth more than his face and his body put together, but I’m sorry.”

Wednesday nights. In Oakland they have a saying: “Wednesday is Toozday.”

“This last thing is just ridiculous. [Matuszak is being sued for $1.5 million by three people over an incident at a male strip club in San Francisco. According to what the plaintiffs told the newspapers, Matuszak came in drunk, took the microphone away from the master of ceremonies and chased him off the stage with a chair, then tackled a male stripper and ‘expelled him from the stage,’ and then lay down and fondled himself in front of the audience. The plaintiffs said it was insulting and lewd.]

“Nobody even got hurt. I just walked in and suddenly this little bastard is tackling me. Big people are targets anyway….”

Slowly, as he talks, he lifts his hand over a fly moving across his stomach. The voice never changes. “And then,” he says, “there was this little dumb-ass fly that picked the wrong day to cross the Tooz….” The fly has come all the way up from his leg, across the bathing suit and is halfway across his stomach when the sun goes out. He senses something is wrong and stops, but by then it is too late.

Matuszak picks up everything but the wet spot left on his stomach and holds it in front of his face. “But you can’t sue me,” he says, “you’re a fly.”

He tosses the body into the grass. “When I come home, I try to take it easy,” he says. “I’m mellowing now. I lie in the sun. Run, lift some weights. Wednesday nights I go out.”

Wednesday nights. In Oakland they have a saying: “Wednesday is Toozday.” You might remember it was the Wednesday before the Super Bowl when he pulled a $1,000 fine for drinking on Bourbon Street until the sun came up, causing Philadelphia Eagle coach Dick Vermeil to say, “If he was an Eagle, he’d be on a flight back to Philadelphia right now.”

Causing Matuszak to say, “Why would anybody want to go to Philadelphia in the winter?”

It was a Wednesday night in Kansas City when he mixed Valium and alcohol at training camp and “died” on the way to the hospital. The head coach, Paul Wiggin, who beat on his chest to get his heart going again, would say, “The last time I saw John he was in a straitjacket.” It was a Wednesday when he threw two people through the door of a bar near Oakland. It was a Wednesday he was picked up for drunk driving and lost a truck commercial he had agreed to do.

“All the things you hear about my reputation, just keep this in mind. If it wasn’t for Wednesdays, I’d be clean.”

It’s not Wednesday, but it is the Fourth of July, and before dinner we go out for a quick one at a picnic a couple of miles from his folks’ house.

Autographs, pictures, high school friends with babies hanging on their legs. See and be seen.

Going home, Matuszak stops for a pack of Juicy Fruit gum, so the folks won’t know what we’ve been doing.

By then, Marvin is cooking steaks on the grill, Audrey is setting the kitchen table. Marvin is a supervisor at the power plant. He doesn’t talk much except when he’s got something to say. Sometimes John calls him stud.

After dinner, Marvin and Audrey get dressed to go to church. “You boys have a nice time tonight,” she says.

John takes her in his arms. He says, “Don’t worry about that, good-lookin’.” Marvin just smiles. You’ve got to like Marvin.

We go to 13 bars that night, then to a party. Between bars, he corrects bad driving habits, runs an occasional red light and splashes himself with Polo cologne.

It is about 15 miles north into downtown Milwaukee. Matuszak gives seven and a half miles to the radio and seven and a half miles to other cars. He tells you who is singing, what year they made the records. He corrects drivers and offers advice. Once, he screams, “You dumb —-” through two closed windows at 65 miles an hour and the noise makes the man in the next car jump. He jumps once at the noise and once when he sees Matuszak pointing at him with an arm the size of a side of beef.

“Maybe that isn’t much, shouting ‘You dumb —-’ at somebody,” he says, “but maybe I saved somebody’s life. Maybe next time he’ll remember to signal.” Another car changes lanes and slows in front of us. “What all these people need,” he says, “is a slap across the head.” A minute later he says, “What I don’t need is the lawsuits.”

We go to 13 bars that night, then to a party. Between bars, he corrects bad driving habits, runs an occasional red light and splashes himself with Polo cologne. Before we walk into the last bar—a nightclub where, at two in the morning we are sitting with the five prettiest girls left awake in Wisconsin—he washes my arm with it.

The five girls all mention that John is an orchid, then one of them sees I am feeling left out and hugs my arm. She says, “You smell good, too, only maybe you use a little too much.”

A minute later we are invited to the party. Matuszak says, “What do you think, stud? Let’s go see if we can find some girls.”

It is a quarter to seven when we finally get back to Marvin and Audrey’s. There is a light on in the kitchen. Marvin always gets up early.

“I love my folks,” Matuszak says. “All I want out of all this is to be able to take care of them, move them wherever they want to go. If they want to move anywhere…”

He unwraps a couple of sticks of Juicy Fruit and sprays himself one last time with the cologne, so they will not know.

Marvin knows. That afternoon he smiles. “You boys deserve it,” he says pleasantly.

John is in the backyard, talking to his toe. It is swollen and crusted black. “You want a day off, don’t you?” he says. He chuckles. “Not yet, not yet. Maybe Wednesday.” He moves over to give me part of the blanket. “How you feelin’, buddy?”

After a while he says, “I thought we were going to get lucky last night. I don’t know what happened.” A little later he says, “I guess they couldn’t figure out what to do with the extra girl.”

We lie there a while, thinking about an unfair world. We lie in the sun half an hour and then Matuszak gets up to kick the hill’s ass again. I go inside, sick and hot, to kick a bottle of beer’s ass. His mother is sitting in the kitchen. He dresses warm and heads out of the house, singing “People say I’m crazy….”

Audrey smiles. “John thinks he can sing,” she says. She listens for a minute, making sure. “He can’t.”

It develops Audrey Matuszak keeps scrapbooks. Everything John does goes somewhere. There is a scrapbook for the good things and a scrapbook for the trouble. Counting graduation, cousins, family picnics and publicity shots from the movies, the good one is a shade bigger than the bad one.

We go out on the back steps to look at pictures. John with Ringo Starr and Barbara Bach in his last movie, Caveman. John with his old friends, Kenny Stabler and Ted Hendricks. An article in Esquire. “The girl wrote that John didn’t wear underpants,” Audrey says. “As soon as I saw that I went out and bought him 12 sets.”

She shakes her head and turns pages. Girls hugging him, sitting on him, kissing him. “You wouldn’t believe the girls,” she says. “They crawl all over each other to get near the football players. I don’t know how they are around you…”

“It’s just awful….”

“I don’t know,” she says, “maybe I’m just old-fashioned, but when I was a girl we didn’t chase boys. I mean, this motorcycle-club girl came over to see John last week and everything she said was mother-this or mother-that. I never heard such language from a girl. And then she hit him right in the face. You could hear the crack. I thought she’d broken John’s nose. I don’t know, maybe I’m old-fashioned, but we didn’t do that when I was young.”

John comes back, sweating, blowing his nose in a paper bag. He drinks a quart of apple juice he gets from the refrigerator, he kisses his mother. “How you feelin’, good-lookin’?”

That afternoon, the yard fills with relatives. Three of the girls climb into the swimming pool, one of those that sits on the ground instead of in it. Leaves float on the surface, ants climb on the leaves. The girls sit in old inner tubes while Matuszak runs along the pool wall, and in five minutes he has created a whirlpool. The girls, the bugs and the leaves float in smaller and smaller circles, until finally they all come together in the center.

Later, he invites me outside to toss the shot put while there’s still daylight. The shot is in the garage. An old three-color cat sits in the doorway and bristles as he comes past. “That cat’s been here 12 years,” he says. “She’s let me touch her once.” He brings the shot out, trailing spider webs, and we go behind the garden to throw it around.

Matuszak was the state champion in high school, but for a while we just toss it back and forth—maybe 35 feet—then suddenly he lets it go. The shot carries over my head, over the garden and lands in a pile of freshly dug dirt over by the trees.

He looks at what he has done and covers his eyes. “Skipper,” he says, “I’m sorry.”

THE BAY AREA

“The greatest dog I ever had was Dax. But I wasn’t around enough, and Dax went bad alone. Every time I brought a girl around, Dax wanted to bite her ass off, and that got to be a problem. I mean, he wasn’t kidding around. So I got him another dog, but all that did was give him somebody to practice on.

“Finally, somebody stole them both. Right out of this motel.”

We are sitting at the bar at the Oakland Hilton, where Matuszak stays before training camp opens. He rents an apartment only seasonally.

It is six in the afternoon. He had laid in the sun two hours, lifted weights, had his car washed, gotten license plates—the old ones expired in 1978—signed 60 autographs and then some legal papers to turn himself into a corporation. “I realize I have certain responsibilities,” he says.

The bartender pours him a triple shot of Crown Royal over ice without being told. Before Matuszak had come in, he’d said, “John’s the greatest guy in the world when he isn’t drinking.”

Of course, any bartender who says something like that is unethical, but he was wrong, too. By its nature, drinking involves some narrowing of goals; in fact it can get a lot like sighting down a rifle barrel. I’d seen Matuszak get that narrow look in his eyes a few times, but he’d never pushed anybody or hurt anybody or even picked anybody up and dropped him on his head. A 45-year-old man tried to butt him in the face in San Francisco and he’d walked away. A hundred people punched him in the arms and stomach and he never punched them back. And anybody who can’t appreciate a little confusion in a male strip club is hopeless anyway.

“How do you steal a dog that wants to bite your ass off?” I ask.

“I’ve wondered what that must have looked like,” he says.

Three hours later, on the way across the Bay Bridge, he feels around under the seat for his tapes. The tapes aren’t there. “Somebody stole my music,” he says. “I know who it is, but I didn’t think he had the sand.”

We pass Treasure Island, then Alcatraz. “If the cops ever stop us,” he says, “the plan is, you jump over here and I’ll jump over there, and while we’re jumping around they’ll never figure out who was driving.”

If there is anything in this world I like, it’s having a plan.

The cruise tonight starts high and aims low. First we hit places where nobody uses the bathrooms for taking cocaine. That part doesn’t last long, because there aren’t many places like that in San Francisco. We move through nightclubs, neighborhood bars, punk bars. We are about bottomed out when we run into five maggots sitting on a bicycle stand outside a basement bar where the bartender is a 40-year-old man in a Bo Peep dress.

One of the maggots stops in front of Matuszak to ask for money. He says, “Hey, man, you got some change?” and sticks out his hand.

Matuszak shakes it. He has been doing that all night, signing napkins, posing for Polaroids. “John Matuszak,” he says, “number 72, Oakland.”

The maggot pulls his hand away, that brings the others in closer. “What you got on?” one of them says, smelling. The one who says that has a bottle in back of his leg, where Matuszak can’t see it. I move closer. If John gets his nose cracked again, his mother is going to kill me. The maggot, by the way, smells like a maggot.

We stand there on the sidewalk for a few seconds, everybody staring and smelling, and slowly the one with his hand behind him pulls it out, changes grips and takes a drink of wine.

Suddenly, Matuszak walks through. The maggots get out of the way, then they shout behind us, “Hey, big man. You know any words? Can you talk?”

The bar is exactly as nice inside as it is outside. As soon as we’ve got drinks a lady pimp dances over and asks Matuszak, “Did you come in for a man? Is that what you’re looking for?”

He says, “No, good-lookin’, I’m lookin’ for you.” She goes back to her table, complaining about the quality of people they’ve been letting in lately. “I wish to [goodness] you’d put somebody on the door, Alice,” she says to the bartender. He shrugs.

We have been sitting half an hour talking to Alice when John leans over and whispers. “Don’t look around, and don’t say anything, but every one of those guys over near the door is undercover.” He pulls back a second, looks into my eyes. “Cops,” he says.

And that, involuntarily, triggers the plan. I scream, “Narcos!” and jump into his seat. Matuszak, however, doesn’t jump into mine, so I am sitting in his lap, and the lady pimp comes by. “That’s what I thought,” she says.

“From now on,” he says later, “anything I say, wait two minutes before you look around. Wait two minutes before you do anything.”

At two we are back in Oakland, buying a couple of six-packs to get us back to the Hilton. “I’ve been doing a lot of reading lately,” he says.

I am waiting for him to finish that when three girls in a nine-year-old Dodge stop on the street and roll down their window. It isn’t surprising when he leans in and half a minute later two of them get out of the car and follow him back to his.

“You ride with her so nobody gets lost,” he says. We split up the beer in case somebody does get lost and I get into the Dodge. “Is that really John Matuszak?” the girl says.

“Yes it is. Would you like a beer?”

“There’s an opener in the glove compartment,” she says. “That’s my little sister in there with him.”

I can’t find the opener, so I pull out two bottles, put their caps together and jerk them apart. Both bottles spit foam; neither opens. I am wet and half blinded, and she reaches over and twists the tops off. “Is he as smooth as you are?” she says.

The room doesn’t look like John was expecting guests. There is a chair sitting in the middle of a pile of sheets on his bed, a brassiere on the chair. There is a pair of panties that matches the brassiere hung over the light on the table.

The floor is covered with clothes and magazines. Playboy, Penthouse, High Society. He said he’d been reading. We have a beer. The two girls who had come with Matuszak look around and decide they are hungry. The one who brought me tells them to stick around. “Hey, the writer’s funny. He spills things on himself.”

The girls think they want a pizza anyway. John thinks they want a pizza, too. “Pete,” he says, “why don’t you go with those two so they don’t get lost?” I think of all the things I have heard about Matuszak when he’s been drinking.

I open a fresh beer and sit in a pile of T-shirts on the chair and smile. “What I mean is, maybe you could go with them,” he says. He nods toward the door. I nod toward the door, too.

He says, “You probably ought to go along with them, this time of night in Oakland.”

“Oakland? I’m not going out at night in Oakland.” It takes him 20 minutes to talk me out into the night and then, at the elevator, the girls change their minds anyway. “I’m not leaving her alone with him,” one says. “She’s my sister.”

A minute later, John and I are four beers from all alone in Oakland, California, at quarter to four in the morning. They were there, and then they weren’t. His eyes are six hours squinting down the old barrel and he is a long way past caring that a story is being written.

John Matuszak shrugs. “It must be that extra girl again,” he says. “If we’d had one more, we’d of been all right.”

And two days later we are crossing the bridge back to Oakland in the suddenly quiet limousine the size of a cattle truck. Matuszak has spent the two days getting ready for training camp and five weeks of self-denial.

There was a girl who flew in from Denver with trick underwear, a girl he met at the carwash, a stewardess who turned out to be bald.

When he took a couple of hours off and left his room, somebody broke in and stole his new license plates.

After the stewardess, he’d said, “Sex is all right, stud, but if you want it to be great, you got to be in love.”

We have been to Los Angeles to test microphones for a television commercial and to sign papers for Matuszak’s first starring movie role, as Paul Bunyan. The executive producer of the film is a woman named Allison Caine, and she told me this at least three times: Nobody understands Johnny. They pay him to be outrageous.

We have also washed the car, lifted weights, run, posed for pictures and signed autographs for 200 Boy Scouts at seven in the morning at the airport.

I am wondering if George Allen would have done that when, without warning, Matuszak explodes out of his seat. He makes a noise that sounds like the last thing you might ever hear and falls across the aisle onto Donna, the girl he cares for above all others.

He kisses her mouth, her nose, her breast, her other breast, and buries his head in her dress, making rooting noises.

I smile over at Donna, pat her hand. I smile at Matuszak, too. The new, incorporated, responsible Tooz, on the way to stardom on the silver screen.

He must have been hell before he mellowed.