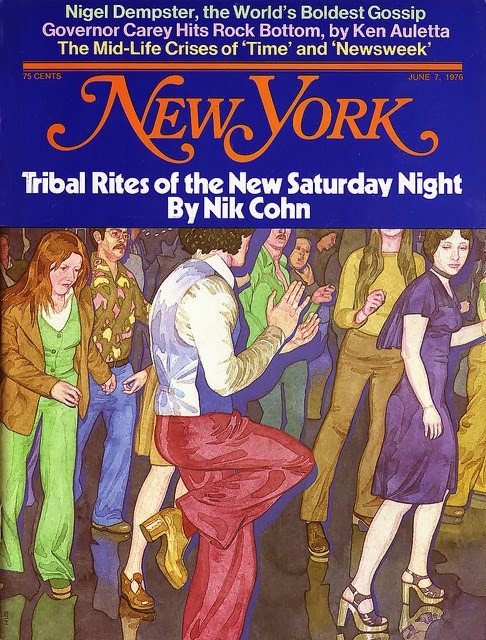

New York magazine is celebrating its 50th anniversary this year and they really pulled out all the stops with this big, fat, sexy coffee table book. It’s really well done and so worth having. Some of New York’s most famous stories are in there, including Nik Cohn’s 1976 feature, “Inside the Tribal Rites of the New Saturday Night,” the basis for Saturday Night Fever. From Mark Rozzo’s excellent 2011 New York Times magazine profile of Cohn:

Without Cohn’s original story, it’s possible that disco would be a dimly remembered fad from the days of the Ford administration: no Bee Gees megahits, no Travolta superstardom, no nostalgic polyester parties for decades ever after. Barry Gibb reportedly once said to Cohn, “It’s all your bloody fault, isn’t it?” He may have been right.

“Saturday Night” would prove to be a blessing and a curse. The story — turned out with the writer’s customary brio — would provide Cohn with a financial cushion and a degree of fame that he still enjoys. But it would forever bind his reputation to work that even he insists was “contaminated.” When the article ran, it was accompanied by the assurance that every improbable, impressionistic word was true. In fact, Cohn made most of it up. After years of mea culpas, he is still queasy about this chapter of his career. It’s his biggest hit, and he cringes every time it gets airplay. The rest of his work, Cohn says, is not even “a wart on the fanny of ‘Saturday Night Fever.’ I’ll always be known for that.”

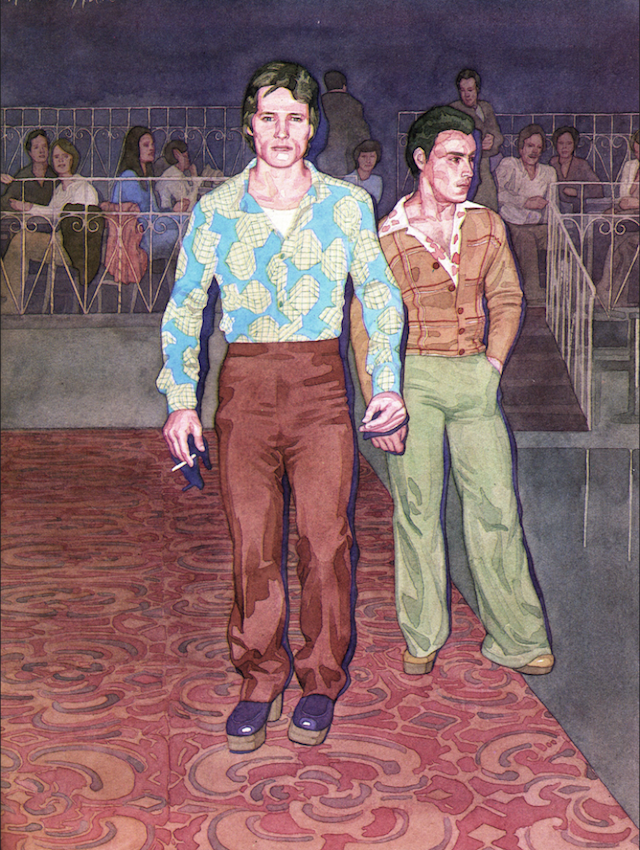

But it wasn’t just Cohn’s prose that made the story come to life, as they were accompanied by James McMullan’s bewitching illustrations. McMullan, who is most famous for his work at Lincoln Center, was a terrific magazine illustrator in the ’70s, a period he details with keen insight in Revealing Illustrations. I visited Jim at his Upper West Side studio recently and we chatted about the famous Saturday Night piece.

Alex Belth: When you accompanied Nik Cohn to a few Brooklyn to research the story did you stick with him in the clubs or go off on your own?

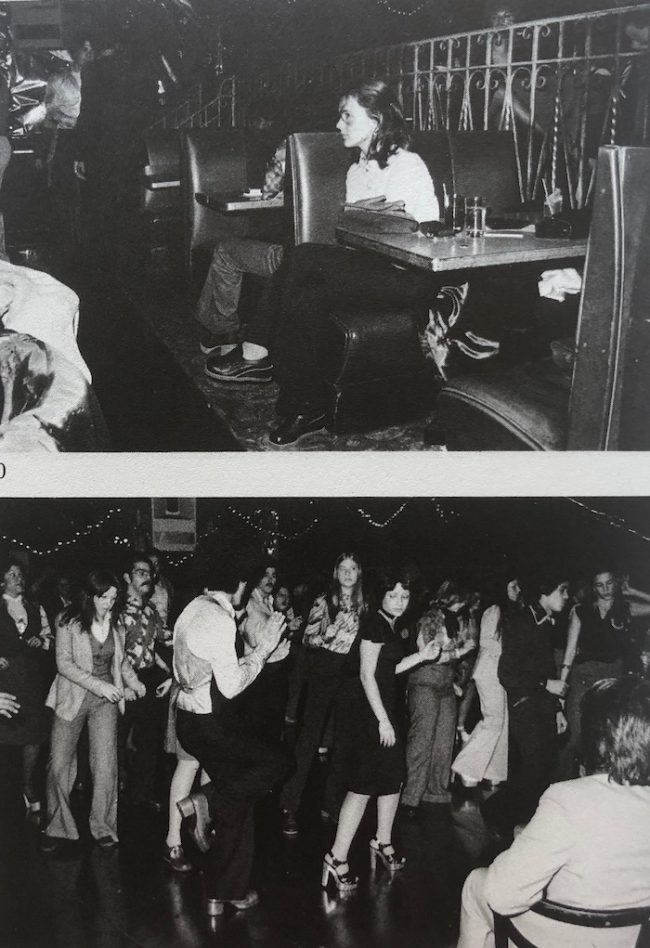

Jim McMullan: I had a car, so I drove us out there. We went to three different clubs and we went twice. He said he went many more times. And yeah, we were separate once we were inside. The first time, I tried to be surreptitious. I didn’t have a flash. I was skulking around, holding my camera low, being as invisible as I could be. Of course, I took my film to the processor and it came back just black with little white dots where the ceiling lights would be. There was nothing. So I realized I had to go back and use a flash. I steeled myself and went to the club manager and said, “I’m from New York magazine and I’m here to take some photographs of the patrons for an article.”

I managed to make myself someone who I’m not: I have every right to be here, I have every right to flash in your face. At first, people were kind of looking, but because I just continued to do it they were like, This guy must have permission. So that’s what I did.

Alex: Did you like the music?

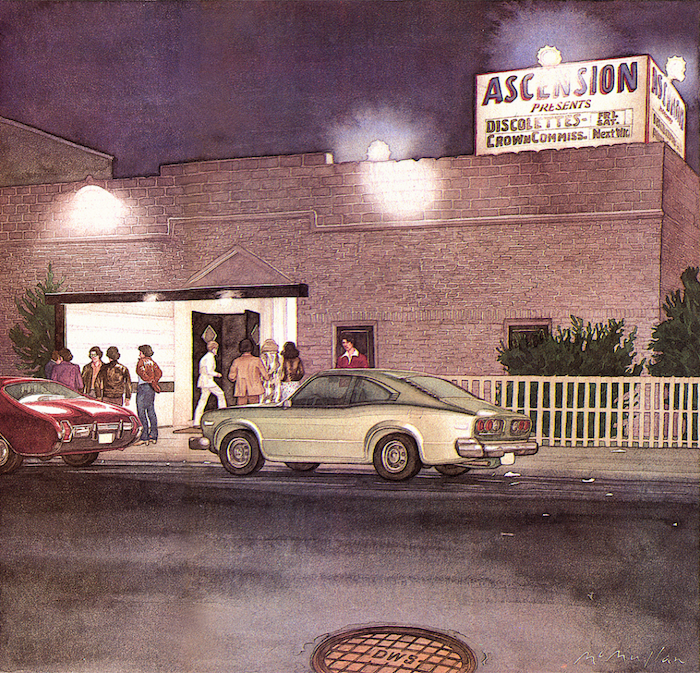

Jim: No, not really. But the psychology of the club was very interesting. Like any situation like that, there were the winners and losers. In the dancing there was so much watching each other. It wasn’t this great performance. People were dancing and there were some really good dancers but there was self-awareness to the whole thing. And also the tackiness of it. I remember one club was basically an Italian dinner club that had been tarted-up with Christmas lights to be a disco.

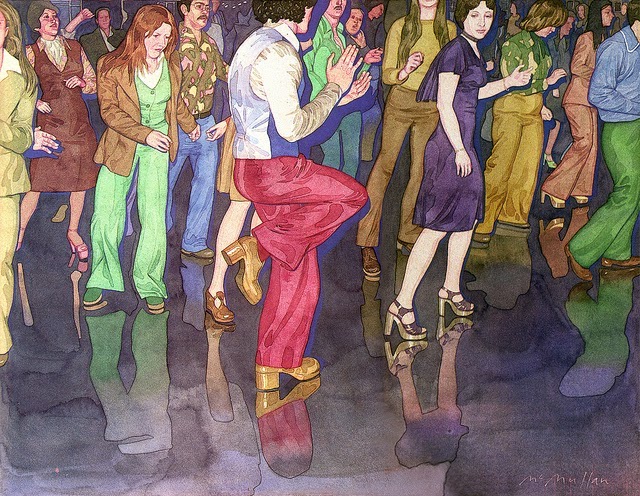

So I get the processed film back and everything is clear as hell. And there were these strange little floating shadows around everything, which is what happens when you use a flash. There is this kind of Halo. I thought, mmm, this is interesting. I began to sketch and say, “How can I make this more dramatic? How can I combine these two pictures into one?” Then I realized, what the hell am I doing? These pictures are incredible the way they are.They were my moments, my moments that I saw, so they already included my point of view. I didn’t want to dilute my experience of those clubs. Because it was a huge moment for me, this somewhat shy guy going into a situation that was alien and in a way threatening and taking those photographs, and then doing the paintings, it was very intense. It wasn’t like a job.

Alex: How long did it take to do the illustrations?

Jim: I did the first painting and it was a more time-consuming process than I had ever had before and sort of unlike any process I had done before because I was really trying to copy the photographs. Accurate isn’t the right word.

Alex: Is this the first time you tried a hyper-realistic style?

Jim: Yeah, I think it is. The halos around the figures sort of flattened everything and brings it to the surface. It wasn’t just realism, I was going for a crystalline quality. I had to replace my usual quality—extemporaneous energy, which his so much of a part of most of my work—with something else. And that became the something else. Freezing the stuff. There was a certain aesthetic that came out of that, and the way I use the color too, to increase the sense of flatness and frozenness. But it really depended on what’s always important to me, which is the intensity of the drawing. Even though it was copying it was extremely intensive copying.

Alex: As opposed to doing it with the projector?

Jim: I used a projector once for an art director who was doing a series of book covers. He said, “Jim, I’m going to insist you use a projector because all the artists who are doing covers for this are using a projector, too.” I was out in Sag Harbor at that point so I called up Paul Davis and asked if I could come over and use his projector. It turned out what the art director wanted but I found it so boring, so boring to be tracing. It’s not a very interesting game. I never projected again. I don’t believe in it. Paul Davis made the point that the only people who could use the projector well were people who could really draw and I agree with that.

With the illustrations for the Saturday Night piece, I wasn’t using a projector, just looking at the photograph and drawing from it. There was a real absorption. I had to understand everything that was going on in the photographs. It was a very intense drawing and painting experience.

Alex: Wait, just so I am clear, you start with a drawing and then you just paint directly on the drawing. Did you ever get tense after finishing a good drawing, worrying that you might screw it up?

Jim: Risk keeps me alive in my work. It’s exciting. I like painting, I like drawing. When I’m really into the work I’m just forging ahead. So, it took me about 3 weeks to finish the first painting—which is the one they ended up using on the cover. I called up Milton Glaser and said, “Come over and look at what I’m doing and let me know if I’m on the right track.” Cause I’d never done anything like it. He looks at the stuff and says, “Keep going, keep going.” He was really behind it. I knew that it was right; I knew that I was onto something. But Milton was thinking about how it served the magazine.

When all the paintings were done he had to convince Clay Felker that they were Okay. Clay looked at them and said, “What are you showing me here?” For Clay, they were too straightforward. They were uninflected moments. “You haven’t done your illustration job, you haven’t pushed it so we understand the point of the picture. Because the picture seems to be about just these people in a club.” I started to defend myself and Milton said, “Jim, go out and wait for me for a minute, I’m going to talk to Clay.” (Laughs.) And when he came out he said, “Everything’s fine.” Clay later came around and was a great champion of the illustrations.

I think all of the paintings took me a couple of months to do. Meanwhile, I don’t know if Nik even started the article by the time I handed them in. So we waited around for Nik. I got so nervous that these paintings I had spent so much time on were never going to be published. But Nik eventually came through.

Alex: Was the response to those pictures immediate?

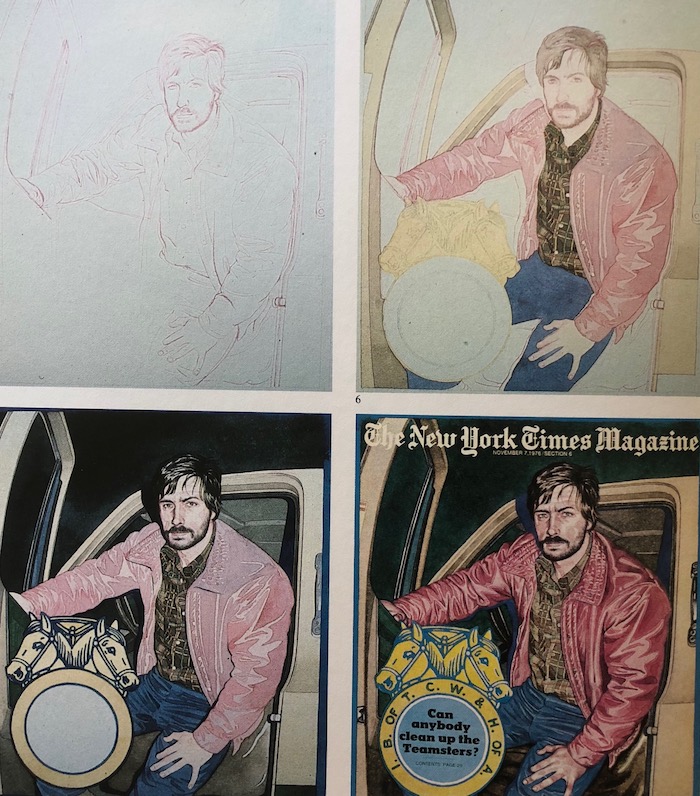

Jim: Oh, man, yeah. The art director for the New York Times magazine called and said, “Jim, those paintings you did for New York, I want something like that.” She made it clear. That was the assignment. Which is how I did the painting on the teamsters. And I got the feeling had I decided to do more of those pictures they certainly would have had commercial appeal. They weren’t really the same as the reconstruction illustrations that I was doing at that time because they were based closely on photos I took out in the world rather than piecing things together from different research, but, I suppose, many people saw them that way. Julian Allen and I were at some point seen as alternatives for this reconstructive illustration but because I never got into it with great enthusiasm and Julian did do it with enthusiasm I was willing to say, You are welcome to that corner of the illustration market-place, I’m not very interested in it.

After I did the job for the Times, I didn’t want to keep doing that kind of drawing. I felt that it was leaving out something fundamental to my work and that was the physical gesture of the hand moving, which is different than copying a gesture. It’s not particularly correct drawing. People think I draw very beautifully and correctly but I’m not sure correctness is right. I make mistakes in drawing but they’re in the service of the psychology of what I’m feeling in the subject. I use a model for the theater posters I do for Lincoln Center. I photograph them. Then I draw from the picture over and over again, and get into it, until it becomes my own. And things change.

[Illustrations via James McMullan]