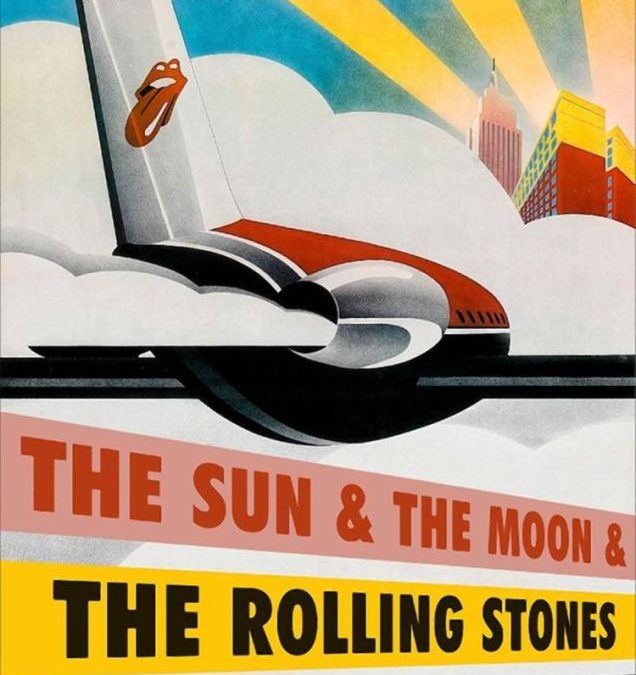

Rich Cohen writes books that are hard to put down. From Tough Jews and The Record Men to his hilarious memoir, Sweet and Low: A Family Story, to the hearty—and heartfelt—appreciation of the 1985 Chicago Bears, Cohen is smart, funny, and above all, entertaining. His latest combines memoir, critical and social analysis and good, old-fashioned reporting and the result is another sure shot. The best book about the Stones is probably The True Adventures of the Rolling Stones by Stanley Booth. Exile on Main Street: A Season in Hell with the Rolling Stones by Robert Greenfield is damn good, too, and The Sun & The Moon & The Rolling Stones deserves on the place next to them on your bookshelf.—AB

Alex: The story of the Stones is really between Mick Jagger and Keith Richards, but originally they were not the focal point of the group, right?

Rich Cohen: It was Brian Jones’s band. Mick tried out and brought Keith with him. When the Rolling Stones were formed, Brian Jones was already kind of famous. According to everybody I’ve spoken to, nobody in England could play slide guitar. They’d all heard it but they didn’t even really know how it was done. And Brian Jones not only could play it—he could play it really well. Keith was really into Chuck Berry, which was considered pop, [not] authentic blues. There was a big fight and Jagger said, “I don’t go in the band without Keith.”

But it was Brian’s vision of the music. He was the best musician. He arranged the songs, he chose the set lists, and he was the one who would talk to the audience. If a reporter called and wanted to talk about the band, it was Brian Jones they talked to. The Stones were his band.

Alex: When did that start to change?

RC: When Andrew Loog Oldman [the band’s manager] told Mick and Keith to start writing. The songs are where the money is. Every time it’s played on the radio, you’re getting money. If you’re not writing the song, you’re like a hired musician. The Stones had some modest hits, and then very quickly—we forget how quickly—they wrote “Satisfaction.” And that was such a huge hit it was the beginning and end of Brian Jones, who famously played “Popeye the Sailor Man” in concert during “Satisfaction.” It was like a “Fuck you, this is shit.”

“Satisfaction” elevated Mick, especially. Because not only was the song a hit, it seemed like a personal statement and branding for Jagger. It made him a figure in a way that “Little Red Rooster” didn’t. He’s the man who smokes the same cigarette as me, and all that.

Q: Were Jagger and Richards natural songwriters?

RC: Jagger and Richards are different songwriters than like Lennon-McCartney, who had the songs just pouring out of them. The Beatles were really organized around the melody, like Irving Berlin and Cole Porter. The Stones were really about the groove. Which is a blues thing. The early Beatles are like almost a ’50s dance band and the Stones were more like a country blues band.

Alex: And their early blues covers are good.

RC: If you listen to an early Stones single like “Little Red Rooster,” it’s a Howlin’ Wolf song and I honestly don’t know which version is better. Not to degrade Howlin’ Wolf at all, because he’s the greatest, but the Rolling Stones’ version is not like a Pat Boone cover. It’s not even like a Beatles song. There’s something really great about it that’s kind of authentic in some weird way. You know, they’ve got a hold of something. Record collectors and aficionados and stuff might dismiss them as fake and white … What’s funny is you’d think that the guys who originally made the music would be pissed off, and feel like they were ripped off. And they were. Some of them were. But a lot of them really liked the Rolling Stones.

Alex: And it took white kids from England to hip white kids in America to the blues.

RC: The joke is, “The longest road from the South Side of Chicago to the North Side of Chicago runs through London.”

Alex: One of the most interesting points of their career came when they released Their Satanic Majesties Request in December 1967, their attempt to ride the Sgt. Pepper’s wave.

RC: By ’67, people started taking acid. The Beatles just rode a tidal wave of right now. I mean [Sgt. Pepper’s] was completely of that moment, so compelling artistically and such a huge hit commercially. It changed everything and everybody felt they had to somehow follow what The Beatles had done, and nobody really knew what to do. Bob Dylan released John Wesley Harding, which was the best response—he went back and just played the guitar. [Their Satanic Majesties Request] is so embarrassing. It bled the ’60s—that part of the ’60s—out of their system. And they said, “Okay, we’re gonna go back to doing what we do.”

Alex: And then six months later they release “Jumpin’ Jack Flash” as a single.

RC: It’s like a forest fire. After a forest fire everything grows, because there’s a lot of dead wood that needs to be cleared. That kind of failure, as painful as it is, will actually clear a lot of shit out that has to be cleared out.

Alex: Then later that year, they release Beggars Banquet and their golden run has begun.

RC: I really like the early Rolling Stones, songs like “Congratulations,” and “Tell Me,” and “The Last Time”—I think that those are up there with any of the other songs. I just think that they were really singles; there was no greater vision. Now, [Guitarist] Mick Taylor was very beautiful and melodic, and that added a whole other element. Producer Jimmy Miller understood how important the groove was. They had kind of lost the groove; they forgot what they were. They’re a blues band, they’re really dependent on finding the groove.

They were almost living in the studio. They were drinking and getting stoned, and doing whatever they were doing. And out of that whole scrum, which reached its ultimate expression with Exile on Main St, the music somehow expressed the vibe of all that hanging out. Once Jagger and Richards stopped hanging out together, the music lost that thing.

Q: They are such opposites, Mick and Keith. You write that Jagger would be happy covering his footprints in the sand, whereas Richards seems liked he’d go down memory lane with you readily.

RC: That’s one thing about Jagger—he’s slippery. He doesn’t want to be gotten. That’s his mystique. He’s smart. He said to me, “What’s going on now is what matters.” He’s never written a book and he will not write a book. And at one point I think somebody gave him an advance, and he returned it. He is not interested in reflecting. Also, he’s not interested in people knowing everything about him. There’s something mysterious and ungraspable about him, just like there is with Bob Dylan.

I think Jagger just realized almost instinctively that when people meet you, the first thing they wanna do is figure you out, and then sort of put you in a drawer and they’re done. Jagger doesn’t let you do that. You can never really categorize him, so he remains interesting.

With Keith, you feel like—I know who he really is. Keith’s probably sitting in his living room listening to some reggae, smoking a joint. And whether or not that’s true, that’s your sense of what he’s doing. What’s Mick Jagger doing right now? I have no fucking idea what he’s doing. That’s what makes the band so great is the sort of tension between the two. It’s all expressed in the music.

Alex: It always seemed Mick had them doing songs that were in fashion, like when they did disco tunes “Miss You” and “Emotional Rescue.”

RC: He was always aware of, commercially, what was hot. The tension is Keith would fight with him, and out of that tension would come this music.

Alex: Keith is seen as more authentic or true than Jagger, especially in the ’70s, keeping everything together.

RC: Jagger was the sober one, and the much more business-minded one. You’ve gotta keep this thing moving forward, or it’s gonna die. There are so many great bands that don’t survive, almost all of them. What they missed was a guy like Jagger, who is like the guy at the party who insists you give him your keys because you’re drunk. And you’re like, “Fuck that guy,” but that guy saved your life. Jagger became an adult. Keith was like—I won’t let you be an adult and have a normal life. I won’t let you enjoy the shit that people normally enjoy. I’m gonna give you a hard time if you get knighted—which anybody would fuckin’ love.

Alex: Yeah, Mick is an easy target.

RC: Even though they’ve had all these problems, they were incredibly close, and deep down are like brothers who can’t really be taken apart from each other no matter what they say to each other. If you go back and watch interviews of Keith, anytime anybody starts ripping Jagger he immediately starts defending him. Which is exactly what you do with your brother.

Alex: Jagger always seemed to have ambitions outside of the band but he never made a memorable solo album.

RC: It’s like your parents—you don’t wanna see them have a good second marriage, you know what I mean? You want them together. And that’s what their manager tried to say to them, which is, “The world wants you together. They want the Rolling Stones. They don’t want Mick Jagger playing with Jeff Beck in Tokyo. Fuck that. You need to be the Rolling Stones, because that’s what people want.”

They’re not as vital as a band as they used to be, but they’re better musicians than they’ve ever been. In the ’60s and ’70s they were not a good band musically—now they’re a great band. That’s partly because they play a lot, and they’re playing at a place where people can hear them, whereas before it just wasn’t as important, you know?

Plus there’s always something sloppy, messed up, and not right about the blues. That’s part of the charm in the blues—it’s about expression. It ain’t perfect. I mean, you could have the greatest guitar player in the world, and he’s not gonna be able to get what Keith Richards gets when he plays sloppy.

Alex: Sometimes it’s interesting to see the choices you made to leave stuff out. You don’t touch on Jagger’s marriage to Bianca because you say it’s boring, and you make a point of not quoting some of Mick’s flowery Sixties ramblings.

RC: Mick Jagger sounding like a hippie idiot because he gave a bunch of hippie-dippy quotes at a time when everybody was giving hippie-dippy quotes is like interviewing a guy the day after he’s lost his virginity, and then holding it against him and quoting him the rest of his life. Let’s give the guy a break, you know what I mean? You’ve just taken acid for the first time in 1967 and said a bunch of stupid shit to a reporter. And you’ll see that shit get quoted again and again, it doesn’t really—to me, it doesn’t signify anything.

Alex: Did your thinking on Altamont change as you wrote this book?

RC: Yeah, I think a little bit. You become more sympathetic to them. I did. Jagger acted unbelievably cool in a way. He didn’t leave. He didn’t stop playing. He believed there would be a full-on riot. He did his best to protect the people who were there and to prevent things from getting completely out of control. And you know, in that situation, knowing that there was a guy up there shooting at me—now whether he was or wasn’t, but that’s what he was told—and to continue on in that case takes a lot of guts. And he never really came forward and talked about it, or told his side of it. But he acted with a lot of courage. The situation was bad because they put their fans in a terrible situation. I don’t think they were smart enough about what was going on in America—they didn’t know about the Hell’s Angels. It was organized too quickly. No one really thought it through. It was the ’60s, so everybody thought everybody would always get along.

Someone asked Mick Taylor, “Was Altamont the end of the ’60s?” He goes, “Yeah. It was December 1969—that was the end of the ’60s.” Ethan Russell—a great photographer who was on the stage—later told Taylor, “You know, when you talk to Americans, they always say that Altamont was this huge deal and it changed everything, you know? And you talk to the Brits, they’re like, ‘What the fuck? It was just a bad show. Something went wrong.’ You know? They never accepted that it was anything symbolic in any way, you know?”

Alex: Taylor contributed so much to those great records but when he wanted to split they just rolled along without him, just like they did, in a way, with Ian Stewart, though Stewart kept playing with them.

RC: The Stones were mad at [Taylor] because he left them in the lurch. You know, they were about to go on tour, and whatever, whatever. You know, he just, one day just quit. And I think that they never really forgot—you know he fucked them over, really. Even though he felt fucked over, he then fucked them over. Ian Stewart’s a whole other thing I don’t really understand, but yeah, I mean, I think that it’s very much is like the dogs bark but the caravan rolls on. You know?

This thing is a machine and it’s going down the track. And if you have a problem, if you wanna get off, you know we’re not stopping, we’re not talking you into it, we’re not remembering you when you’re gone. You’re either here or you’re gone. And that’s enabled them to survive. So it’s like either you’re with it or you’re out of it. If you’re out of it, you’re out of it. Like you never even existed.