The office park is blank and dead. Denver boomed and Denver busted and this is what’s left—a tiny knot of shuttered buildings strung like a browning Christmas wreath around a ruined hillside. Inside, the carpeting is scarred and dirty. The gold leaf on the office doors has flaked away into pointless diphthongs. Wires reach out of the walls, stretching and curling in on themselves and suddenly just stopping in midair, like snakes that have struck once and then frozen. The dead ganglia of communication, gone dumb and twisted. It is a cold place, and dreary. Dan Rather will come here this day to tell the nation about itself.

He arrives on a noon plane, and there’s a buzz that follows him up the Jetway and diffuses swiftly throughout the concourse, seeping into the snack bars and newsstands. He greets a reporter like his richest uncle. He speaks earnestly about a Yankees game he’s just seen, picks up his own luggage, tells the reporter that the reporter’s magazine is “kicking hell” out of its most prominent competitor, thanks P.J. the chauffeur “for being with us today,” talks a little bit about a JFK assassination piece that he is “in the heartwood of right now” and a little bit more about something that happened to him back in the days when he was “as green as money.”

There is one stop to make, at the local CBS affiliate. He visits the crew, compliments one man’s wife on her cinnamon rolls, wanders upstairs to sass the brass, comes back downstairs and, when he discovers that the reporter’s wife recently had a baby, exclaims “Hey, man. You buried the lead.” Congratulations all around. Then he and the reporter and P.J. the chauffeur go rolling off toward the dead office park. On the way through town, he sees Father Guido Sarducci, in full clericals, crossing 13th Street, surrounded by a considerable entourage.

“Hmm,” Rather muses, “he’s got that anchor thing down, doesn’t he?” It is two hours to airtime.

Pope John Paul II is coming to town, which accounts for the presence of both Father Guido and Dan. It also accounts for a significant level of anxiety among the CBS news staff. Denver is fairly agog about the whole matter. The streets are filled with thousands of glowing young Catholics. Downtown, great souvenir tents have been set up wherein the glowing young Catholics can buy John Paul II T-shirts, sweatshirts, sun visors and a new kind of coffee mug on which, when it is filled with a hot beverage, the papal face appears over the Denver skyline. God alone knoweth what He would make of all of this—the Founder, after all, never was much for merchandising, leaving that to His subsequent Vicars—but that’s not what has the CBS people concerned. It is the fact that this pope and this anchorman have something of a history. In point of fact, Karol Wojtyla has not been good for Dan Rather.

On September 11, 1987, Rather went to Miami to cover the last papal visit to these shores. On the same day were the women’s semifinal matches of the United States Open tennis tournament, which CBS had spent a great deal of money to broadcast. Waiting in Miami to begin that night’s newscast, Rather was informed that the second match was running long and might chew into his broadcast. Depending on where you stand on Rather—and almost nobody stands in the middle—he either flew into a fit of pique and stormed off the set or got caught in the middle of bollixed triangular communications between his people, the people at the tennis tournament and the upper echelons at CBS who are supposed to resolve these sorts of things. Whatever happened, the tennis match ran only briefly over, the sports people threw the network down to Miami, and, for six long minutes, there was dead air.

Now, with Dan and the pope together again, the CBS flacks know they are going to hear about Miami and that Miami is going to open up the entire existing corpus of Dan lore: the Gunga Dan foray into Afghanistan; the night Rather said he was mugged by two neatly dressed men who kept asking him “What’s the frequency, Kenneth?”; the wild ride with the Chicago cabdriver who hijacked him in a dispute over the fare; the complete stranger who belted him in the chops at LaGuardia Airport; the week in which he signed off each broadcast by saying “Courage” to a mystified nation; and, finally, the infamous Six Minutes of Black, which George Bush would use like a club on Rather in their famous contretemps a year later. All of these will rise once more, sturdy and restless ghosts, because Dan and the pope are in the same city again.

Rather moves into one of the empty offices now. Someone has sent out for Kentucky Fried Chicken. “This,” says Rather, biting enthusiastically into a chicken leg, “is the glamorous life of network news.” One of the CBS researchers is a bit puzzled over some intricacies of the doctrine of papal infallibility. The reporter, who learned this material once at the peril of his knuckles, helps her out. Dan compliments the reporter and, by extension, the Sisters of St. Joseph. It is ninety minutes to air.

Earlier that afternoon, the police identified the body of Michael Jordan’s father, which they’d fished out of a swamp in South Carolina. There is some brief discussion over whether the murder of Michael Jordan’s father might just trump the pope on that night’s show. “Let’s talk heresy,” suggests Rather. “Does this lead ahead of the pope?” Somewhere in him there is an old city-room instinct quivering. The pope will make a great visual. That is the reason Dan Rather is in Denver at all. But the pope is not a celebrity murder mystery. There is a brief discussion, and it is decided that one does not lead with the dead father of a basketball player at the expense of the pope, not at CBS News, anyway. “It’s ironic,” Dan says. “If there’s one person in the world who could run with the pope worldwide, it’s probably Michael Jordan.” He goes to makeup. It is one hour to air.

His is no longer the matinee idol’s face. He is 62 now, almost a full decade older than ABC’s Peter Jennings and older still than NBC’s Tom Brokaw. There is a weight beneath the eyes, and just the hint of jowliness, like a penumbra, under his chin. The lines cut deep, petroglyphs of a public career that has been harder than even he supposed it would be. In the preceding month, he dodged sniper fire in Bosnia and went to China for an economic summit, and now he’s in Denver covering a pope who has been bad news for him, and they are putting the makeup on him, and Dan Rather is trying very hard not to look tired. To his credit, he succeeds, most of the time. It is forty-five minutes to air.

He is a fullback in a scatback’s world—not quick enough to get out of the way of his own presence. It hangs around him like a shawl too thick for the season.

Afterward, he talks briefly about all of it: Miami and what Bush did with it to him. Again, the talk turns to the reporter’s new baby, and the fried-chicken dinner, and even Father Guido Sarducci. The schmoozing is relentless, but there is a kind of studied formality to it. It is not ironic distance: Dan Rather is the least ironic man alive. His attempts at informality seem curiously bounded by some code of manners that comes from his bones. There is a tension there, fierce and unresolvable, between who he thinks he has to be and who his deepest self says he is. Finally, he smiles, and he pats the reporter’s tape recorder gently. It is thirty minutes to air.

“Well,” he says, “I don’t know what I can do to help you, except to do something to embarrass myself again.”

He is not loose. He does not jangle. He moves only at the hips and the shoulders, all stolid purpose, through the dark lobby and into the heart of the noontime power-grazing at an uptown Manhattan hotel. Heads turn. Voices drop. The air is charged and almost sickly with portent. He is a fullback in a scatback’s world—not quick enough to get out of the way of his own presence. It hangs around him like a shawl too thick for the season.

“I’ve never gotten comfortable with the celebrity side of it,” he says. “I’ve learned to deal with it. I’ve grown at least adequate at dealing with it and, I think, on my better days, better than adequate at it.

“Maybe I’m out of fashion. I don’t know.”

Whatever one may think of him, Dan Rather is larger than life. He looms, figuratively and literally, over the industry of television news. “I’ve worked with Jennings and I’ve worked with Cronkite and I’ve worked with Koppel,” says Tom Bettag, the executive producer of ABC’s Nightline, formerly Rather’s executive producer for five years. “I’m telling you, there’s no comparison.” On the air or off, Rather shakes the very air around him, for good or for ill.

This is what put him in Bosnia as the bullets popped around him. This is also what makes so many of his former colleagues spit nails at the mention of his name. This is what put him in Tiananmen Square hours before the tanks rolled in. This is also what cast him as (at best) Iago in all those books that sprouted like poison mushrooms about the turmoil at CBS News in the 1980s. This has been the making of him. This has also been the unmaking of him. It can be a difficult job being Dan Rather, especially when Dan Rather keeps getting in the way.

For example, in 1990, as more and more American troops began spilling out into the area around the Persian Gulf, Rather turned to Connie Chung, who would become his most improbable coanchor, and said “I’m told that this program is being seen in Saudi Arabia… and I know you would join me in giving our young men and women out there a salute.” Whereupon, with Chung looking as though she’d been hit in the head with a brick, and with his portion of America dropping their jaw into the pot roast, Dan Rather went snappily to his forehead.

Later, though, at the end of a war during which the United States government went to unprecedented lengths to keep Rather and people like him from doing their job, he was most eloquent in his denunciation of the media’s sorry complicity in its own gelding. “When I covered the White House,” Rather told author John MacArthur, “you certainly wouldn’t be able to drink with the big boys if you caved [in]…. Now, read the best papers in the country…. Suck-up coverage is in.” Without the salute, he wouldn’t be Rather. But without the pang of public conscience, he wouldn’t be Rather, either.

“I’m not sure he wants that struggle to go away,” says Bettag. “He has intentionally kept that torment alive.” Other people are not so kind. “I don’t think Dan is evil,” says one former CBS executive. “The problem with Dan is that there is no Dan. I think he makes it up every day.”

Now, he is supposed to be miserable and depressed—when it is not alleged that he is, well, unhinged. The CBS Evening News occasionally noses into second place, but it has been hopelessly behind ABC and Jennings for nearly five years now. He is in the tenth month of the misbegotten anchor partnership with Chung, who, seated next to Rather, forever seems in danger of floating out a window. Some rumors have him sleeping sixteen hours a day on weekends. “I saw him at CBS last year,” says a former colleague. “I wanted to reach over and say ‘What’s wrong, Dan? What’s eating you?’ But, of course, I didn’t.” Author Stephen King has been widely quoted as saying that he watches the CBS Evening News specifically in case Rather freaks completely on the air. This is not the sort of endorsement one wants from the author of The Shining.

In a sense, he did fall out of fashion. The business changed on him in the 1980s. Television news became seriously entangled with the business of television. This came as a particular shock at CBS, where the news division was possessed of a haughty grandeur that would have embarrassed the Avignon papacy. A bloody civil war broke out between the Old Guard, who saw any change as surrender to the cheap and sensational, and the New, who saw their counterparts as a collection of stubborn fogies. The discord lasted almost the entire decade. During this angry time, Dan Rather became the anchorman of the evening news. This put him squarely in the middle of the conflict even as he was trying to define himself as the replacement for the legendary Walter Cronkite. The pressure on him was vast and crushing.

In the end, it was all a battle of toy boats and rubber ducks. The fact is that network news has always been an adjunct of a financial entity that survives through entertainment. At best, it is what the old immigrant priests used to call “conscience money,” the stained-glass-window purchase that supposedly evened things out for all the bookmaking. Only the naive, or the criminally foolish, ever put much reliance on the essential moral conscience of a television network.

For his part, through all the sniping and all the carping, and along the incredible trek through dark weirdness that has been his career—What is the frequency, Kenneth?—Rather shrugs his shoulders and soldiers on. There was some talk that he would, as he inevitably says, take it to the ranch at the end of his last contract, in 1991. However, for all his faults, the one great constant about him is that there is always a story he needs to cover, one more fence line he needs to ride. He is the last of the TV cowboys.

Back in July of last year, Rather was visiting a man named Harold Ludwig, the mayor of La Grange, Missouri. Ludwig was afflicted with a bad case of catfish in the kitchen. This was because Ludwig’s kitchen was afflicted with a bad case of the Mississippi River. Water up to his sternum, Rather walked politely behind the mayor into his home. If the welcome mat hadn’t been five feet underwater, Rather undoubtedly would have wiped his feet. Maybe he did anyway. The two of them waded down the long hallway, past a capsized dining-room table, through a covey of floating coffee cups and into the kitchen.

“You know,” Rather told Mayor Ludwig as a blender floated past him toward Iowa, “you have a nice home here. I’d like to see it at another time.”

He looked far more at ease as a well-mannered houseguest in the middle of the pond in the kitchen than he does now in the Manhattan hotel restaurant, where the air crackles and snaps, and where the heads turn and the voices drop. “In many ways, the Eighties was a great decade for me,” he insists. “Not everything that happened in that decade was terrific to me, but I got to be in Tiananmen Square. I wouldn’t take anything for that.

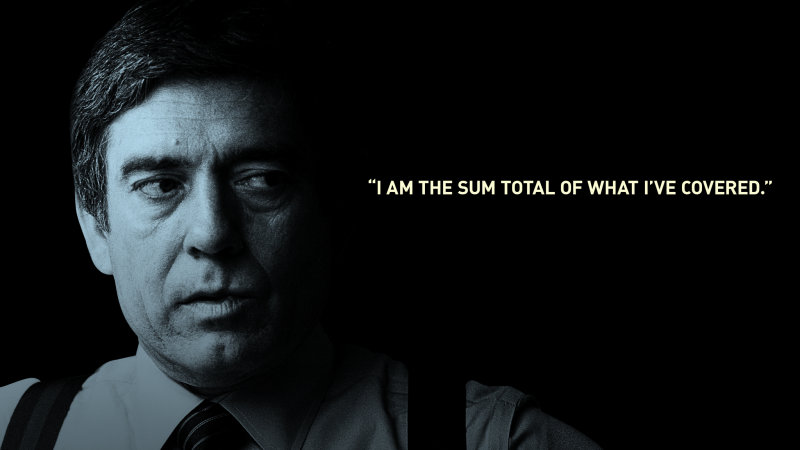

“I am the sum total of what I’ve covered. I don’t have an apology for that. Maybe I care too much. Also, I didn’t come into this game chicken. I didn’t come to CBS to be just another correspondent. I wanted to be a great correspondent. I am still trying to be a great correspondent. And I do believe that my best work is still ahead of me.”

Ultimately, it’s the anchorman’s job that has muddled his legacy more than anything else has, rendering him not a towering figure among CBS correspondents but a hugely curious eccentric. It brought him to New York and into celebrity and all that celebrity entails. It tries to draw him away from the grunts on the battlefields, and from all those ordinary people with catfish in their kitchen. As often as he insists that he loves working in the studio, Rather misses no opportunity to flee what he calls the “hothouse atmosphere” of West 57th Street. If there is a “good” Rather and a “bad” Rather, the good one is walking the levee, polo shirt open at the throat, talking about the sound of shovels scraping on the concrete of a failing dam. His professional conscience is out on the far fence lines of the news.

He is flotsam, blown north to CBS by Hurricane Carla in 1961. Rather was the news director at KHOU in Houston. To cover Carla’s arrival, the 30-year-old Rather lashed himself to a seawall in Galveston and reported the storm’s landfall while looking very much as though he was about to be blown to Cotulla and back. He covered everything as if it were a war. The CBS brass was impressed—even if he did drip Texas like rhinestones from a country picker’s lapels.

The Texas part of him is undeniably genuine, if somewhat cultivated. “I am a Texan both by birth and by choice,” insists Rather, who proves his bona fides in this regard by citing (correctly) Jimmie Dale Gilmore’s rendition of “I’m So Lonesome I Could Cry” as the finest Hank Williams cover of all time.

He grew up in Houston Heights at the tail end of the Depression. His father was an oilman who dug ditches and put down pipe. As a boy, Rather contracted rheumatic fever—its recurrence years later would cause him to be discharged from the Marine Corps—and he was bedridden for most of his adolescence. He was weak and sickly in a culture that was not kind to either condition. “The only thing they could tell you was to go to bed and be still,” he recalls. “For a young boy, that’s hell. l was in bed for almost a year once. l went back to school, and l couldn’t play. l loved sports, and I was reasonably good at them, but I realized how thin I was, and how weak.”

His companion was the radio, and the great crackle of the distant war news. It was a beam he followed all the way through Sam Houston State Teachers College, all the way through his courtship of Jean Goebel from out by Winchester, and all the way from KHOU to New York, where he arrived pure Texan. “The first time l ever laid eyes on Dan, my wife and l invited him to dinner,” says Peter Herford, who worked with Rather both in New York and in Vietnam. “The doorbell rings, and I open the door, and he’s standing there in a sky-blue suit, polyester, with a brown tie, white socks and brown shoes.”

He arrived very much the former marine, all gung ho and parade-ground machismo. He learned quickly that he was being lied to, that the United States military does not always do right in the world and that it often is not honest with the soldiers it sends out to fight.

In 1962, CBS News was many things, but it was not sky-blue polyester suits. CBS owner William Paley once called the division “the jewel in the crown.” Cronkite was on his way from newsreader to American icon. There was an ineffable style to the place. Advanced degrees hung like ivy on the walls. Murrow’s boys knew their way around Savile Row as surely as they did Washington or Moscow. It was a desperately long way from Houston Heights, and Rather fairly hummed with insecurity. For the first time, Rather felt himself pushed to be something he was not.

He tried to fit in. Sometimes his efforts were effective. Sometimes they were simply comical. One legendary story has Rather asking a CBS colleague if he had read Edward Gibbon’s The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire “in the original Latin.” At the same time, he made his bones as a ferocious and indefatigable correspondent. If personally he was marked by the two great news stories of his youth—the Depression and World War II—professionally, he would be shaped by those of the Sixties and Seventies. He was in Dallas when John F. Kennedy was murdered, and he was in the South for the turmoil of the civil-rights movement. And he went to Vietnam.

He arrived very much the former marine, all gung ho and parade-ground machismo. He learned quickly that he was being lied to, that the United States military does not always do right in the world and that it often is not honest with the soldiers it sends out to fight. As much as his personal style was shaken by his arrival in New York, his personal values were shaken in Vietnam. “Of all the trusts I had in Vietnam,” he says, “the one I felt the strongest about not breaking was the trust given by the people who were actually fighting the war.”

He was not the writer that Murrow was, nor did he have the intellectual heft of Eric Sevareid, but for balls-out, shoe-leather reportage, he was their superior in every way. In 1968, at the tumultuous Democratic Convention in Chicago, Rather got flattened by one of Mayor Richard Daley’s security goons. As Cronkite looked on, aghast, Rather piped up from the floor, “Don’t worry, Walter. I’ll answer the bell.” Four years later, some ex-CIA stooges in the employ of the Nixon reelection campaign broke into the Democratic Party’s offices in the Watergate apartment complex in Washington. In so doing, they shot Dan Rather into the stratosphere.

More than anyone in television, he dogged the story, piecing together bits of information and filling in the cracks with informed speculation. The pressure from the White House was grinding. “There were times,” he says, “when Jean Rather and I looked at each other and I said to her ‘We have all the chips on the table here. If I make one mistake, I’m probably finished.’ ” Once, while wandering the country trying to plead his case, Nixon confronted Rather at a broadcasters’ convention in Houston.

“Are you running for something, Mr. Rather?” asked Nixon.

“No, sir, Mr. President,” replied Rather “Are you?”

It was not a marine’s reply to his commander-in-chief, but it was a reporter’s reply to his subject. The person formed by the Great Depression collided with the reporter formed by Vietnam and Watergate. The reporter won this round. Later that summer, however, Rather claimed to find “a touch of majesty” in Nixon’s cheap, alibi-ridden resignation speech. That time, the reporter lost out to Rags Rather’s son. “I so badly didn’t want to believe what was happening that I refused for the longest time to believe what I knew,” Rather says.

By the end of the 1970s, Rather had gone as far as he could as a CBS correspondent, even though 60 Minutes was making him nearly as big a star as Cronkite, who was openly hinting that he would step down. There were some questions about Rather’s image. In November 1980, in Chicago, he got into the wild wrangle over cab fare; the driver took off with Rather hollering out the window. Rather had the cabbie charged with disorderly conduct. In return, the driver accused Rather of ruining his professional reputation. This was not the sort of thing that happened to Walter Cronkite.

Nevertheless, Rather politicked masterfully for Cronkite’s job, playing CBS against Roone Arledge’s ambitious new ABC News operation and totally outmaneuvering Roger Mudd, who had been presumed to be Cronkite’s successor by most of the Old Guard. To Rather, the question was not whether the anchor’s job was a good one for him. It was a simple matter of winning and losing—a Houston Heights bare-knuckle brawl brought to the executive suites of Manhattan: “Someone said, ‘Well, they don’t think you’re anchor material.’ That made me sore. In the context of the time when I came up, there was no way I could be considered the best unless I anchored someone’s evening newscast.” On Valentine’s Day, 1981, Dan Rather signed a ten-year contract that would reportedly pay him $22 million to be the anchorman and managing editor of the CBS Evening News.

It was a pivotal moment. Had he stayed out of the anchor’s chair, he would be revered among CBS correspondents—the hardworking Gehrig to Cronkite’s Ruth. Even now—thirteen years, a platoon of executive producers, myriad troubles and Connie Chung later—all he can say is that he wanted the job mostly because somebody told him he couldn’t have it. It was an awful, final victory for what he thought he should be over what he was. “There’s a disease in him,” says a former colleague. “He’s hooked on it like some sort of heroin. He’s hooked on this damned anchor thing.”

They are making peace on the White House lawn. Yassir Arafat is grinning like someone who just hit the double at Pimlico. Yitzhak Rabin appears to be feeling around to make sure that he still has his watch. Bill Clinton seems to be reviewing the luncheon menu. And, on the CBS News set some yards distant, Dan Rather and Connie Chung are sitting beside each other, and all those people up on the lawn look infinitely more comfortable together than the two of them do.

“We all remember the good old days as being much better than they were. We think they were better, but they weren’t.”

“If a caption writer would put a line under this picture,” says Dan of the scene he’s surveying, “it would be ‘Un-be-liev-a-ble.’”

“Unthinkable,” replies Connie. “One hundred years of hatred wiped out by this picture.” And they look the way they always look—like a prom date arranged by their parents.

Their offices tell as much about them as anything does. Chung’s suite is across 57th Street from the CBS Broadcast Center. It is a loose and funky place; on one bulletin board hangs a list of birthdays of the children of staffers on Eye-to-Eye, Chung’s new show. There is an overwhelming feeling to the place that, at any moment, fifteen people are going to order out for pizza. In her personal office, Chung has a life-size cardboard cutout of her husband, Maury Povich, which seems rather a redundancy. Across the street, Rather’s office is quieter. On the door, in fading gold letters, is the famous quote from Simonides: “Go tell the Spartans, thou who passest by/That here, obedient to their laws, we lie.” A huge family Bible rests on one table, open to the Psalms. It is a long way from Simonides and his dead Spartans to a life-size cardboard Maury Povich.

“I’m actually part of the old crowd because I was here in the early Seventies, when Walter was doing the news,” says Chung. “We all remember the good old days as being much better than they were. We think they were better, but they weren’t.”

There are people who are gloating, enthusiastically and anonymously, over the transparent idiocy of putting these two people together. Even if Rather and Chung were temperamentally and professionally suited to each other—which they are not—a nightly newscast lasts only about twenty minutes, of which the anchor might get six to eight. So, after a decade in which he lost a number of friends, a huge amount of his hard-won credibility and a substantial chunk of his public esteem, Dan Rather is fighting for four minutes a night. Some people see this as his comeuppance for what they perceive to be his role in removing the jewel from the crown.

As late as 1984, the CBS Evening News was still in first place, but in truth, Rather was floundering, searching for a new identity almost weekly. He allied himself closely with Van Gordon Sauter, then an executive vice-president of CBS’s broadcast division, whom most of the CBS News traditionalists point to as the principal vandal of the 1980s. Rather wore sweaters. He began signing off with “Courage.” He became even more of a lightning rod for strange occurrences. Confronted by a persistent interviewer outside of the CBS building—exactly the sort of thing that he had done so well at 60 Minutes—Rather swore into the man’s microphone and then gave him a shove. He later apologized. In the middle of a corporate civil war, Rather’s personal gaffes were exactly what CBS did not need.

It all came to a head in late 1987. CBS embarked on a series of harsh staff cutbacks. Foreign bureaus closed. Budgets shrank. Morale sank like a stone. In many eyes, Rather became the symbol of what was really an inexorable and profit-driven contraction of the network’s news operation. There was a feeling that Rather somehow should have done more than he did to protect the news staff, that he was being far too good a marine.

His face darkens when he is reminded of this, and his tongue pokes into his cheek, which is said to be one of the signs that he is truly angry. He prides himself so deeply on loyalty that this is the most damning accusation of all. “You raised this, I didn’t,” he says, drawing a deep breath. “Show me another practitioner at another network who has stood up for his people more often and at greater risk than I have. I’ve not done it perfectly. I’ve made mistakes. I asked myself what else I could’ve done that I should have done.”

In truth, his lust for this job had trapped him again. His whole upbringing dictated that the boss was the boss, and that you swallowed hard and did what you were told. He had no great gift for self-immolation, and he could no more quit a job than he could fly. However, his stature as a professional lay in telling the powerful to go to hell, and Rather never truly found a way out of this bind.

By the time he got to Miami with the pope in 1987, he had become a far bigger story than anything he could cover. When he was not on the air at the beginning of the September 11 broadcast, Cronkite said he should be fired, and a British newspaper openly questioned his stability.

In January 1988, he set up an interview with then-Vice-President George Bush. The live spot followed a rough piece on the inherent inconsistencies in Bush’s account of his involvement in Iran-Contra. Well briefed by his handlers, Bush turned on Rather, citing the Miami episode specifically but clearly allowing it to suggest everything else that had happened to Rather over the previous decade: “Kenneth” and “Courage” and the great Not Walter as well. Rather blew up in response. It was Houston—“No, Mr. President. Are you?’’—stood on its head.

He has Van Gordon Sauter’s old office now, the one that looks down on the studio and the anchor’s chair. The office is a statement of who he was, who he is, who he thinks he was, who he thinks he is, who he thinks he should be, and who he thinks he should’ve been. It is all of who he has been, every identity that he thinks he has needed, and it is very quiet, hushed the way it would be had one of Simonides’s Spartans been cursed by the gods to come back to life.

Dan Rather was right. That’s the damnable thing about it. Regardless of what you may think of what he did in Miami, CBS has sold itself out to its sports coverage. Delaying the news for a tennis match in 1987 leads inevitably to what happened in 1992, when CBS had a commitment to the baseball playoffs and thus was the only network to miss a presidential debate. And, as events have borne out, Bush was lying his withered hindquarters off about Iran-Contra during their confrontation, and Rather knew it, even if he came off like Goofy Dan, yelling at the vice-president. But Dan Rather was right, damn it. That should count for something.

“Thank you for noticing,” Rather says now, smiling thinly.

His 48 Hours is probably the most underrated show on television, infinitely sharper than any of the other magazine shows despite the fact that CBS has bounced it all over the schedule. He walks up and down a tough street between crack houses, and he looks free and young again, not hunched and old the way he does in the studio, trading clumsy chat with Chung while the world goes by behind him. He looms so large that it is easy to visit upon him the blame for the increased trivialization and corruption of the network news. However, network news has proved fully capable of corrupting itself. NBC goes out and hires Pete Williams, the noxious little dweeb whose job it was during the Gulf war to dole out barefaced nonfacts to the same people who are now paying his check. Meanwhile, Peter Jennings reflects that ABC—which has among its stars a former Nixon apparatchik (Diane Sawyer) and a contributor to The American Spectator (Brit Hume) and which once paid Henry Kissinger a consultancy fee—has been derelict in incorporating conservative viewpoints into its coverage. Whatever Rather’s sins have been, real or imagined, television news sings soprano now because it really has little choice. After all, its news must also entertain.

Recently, Rather has grown outspoken in his criticism of television news. “I was raised in journalism to believe that you had only one client and that was your reader or your listener or your viewer,” he says. “Somewhere along the line, not too long ago, the idea began to take hold that the client was the person that you were covering. Now, I’m saying this with a smile. It’s puzzling to me, and I do lament the change. I didn’t think it was a big deal to ask Bush those questions. I thought he’d have an answer.”

On September 29, 1993, Rather went before a convention of news directors and gave a ringing denunciation of what his business had become. “We should all be ashamed of what we have and have not done, measured against what we could do,” he told them. He cited Murrow. Depending on where you stand on Rather—and nobody stands in the middle—you either applauded or gagged. The next day’s speaker was better received. He was Pete Williams.

Of NBC News.

Dan Rather was right, damn it. That should count for something.

It is airtime.

“Whoo-eee,” says Rather, startling everyone who is crammed into the hallway of the dead office park. “Love that tackle football.”

Outside of the pope and James Jordan, nothing much is going on this day. Rather will do the news standing in front of a window. Unfortunately, there is a man named José outside, washing this window, and he has not yet gotten the word. It is possible that 55 million Americans are going to see Dan Rather do the news with a long squeegee rising and falling behind him. Rather knocks on the window. “Excuse me, sir,” he says. “Thank you for all your help, but could you stop for a minute?” José smiles and comes inside. He will watch Dan do the news from the hallway.

Rather goes up on the balls of his feet. On his face as he stares into the camera is a look very much like the one Marvin Hagler took into the ring for the third round against Thomas Hearns. “Good evening,” Rather says to the nation. José’s face is rapt with wonder. He has done a good job. The window behind Dan is clear, and you can see a long train pulling out of the rail yards below, running south toward Texas. Downtown, the thousands of glowing young Catholics are getting caught in a swiftly moving thunderstorm, ducking into the souvenir tents to get out of the downpour. Dan Rather stands there looking as if he might bust right through the window, but, framed now by the storm, he stays where he is, above all the sacred and the profane, with lightning on his left hand and a rainbow on his right.

[Illustration: Sam Woolley/GMG]