White lightning slams across the sky as the Eastern Airlines 8:00 A.M. shuttle takes off from New York to Washington. In a front aisle seat, a tall, slender woman stares straight ahead through a mask of makeup-black penciled brows, heavy false lashes, orange lipstick, and a black shoulder-length fall made of Korean hair. Her body is covered with Pucci designs of yellow, purple, and pink. Her name, Jacqueline Susann, is a household word; her face confronts the American family on the television screen, in magazines, and on the jackets of books seen on beaches, planes, and buses. The best-selling author, who has made the word “doll” a synonym for pill, opens a small gold box and takes out a pink tablet. “I’m going to take a wakeup pill.” It is uncustomarily early for the Jacqueline Susann $75,000 road show to be under way. In her baritone voice, Jackie explains she decided to take the early shuttle instead of flying to Washington the night before because of her poodle, Josephine. “She’s fifteen, and if I’m away overnight, she has to have a sleepover.” Jacqueline washes down the pill with Binaca, a breath freshener she sucks on through the day, and flips through Harper’s Bazaar.

Beside her is her husband, Irving Mansfield, né Mandelbaum in Brooklyn, thin, with a small, round face that carries an anxious expression although it is usually smiling. Irving was once a press agent for Eddie Cantor, then producer of “Arthur Godfrey’s Talent Scouts,” and now, manager of the campaign designed to milk the resources of Hollywood, Broadway, and Madison Avenue to convert The Love Machine into a commercial fortune.

“Jackie, we wanna be organized,” he says as the plane descends through sheets of rain. Irving carries a bag of Jackie’s dresses and a hatbox full of makeup and hairpieces. In the limousine, Jackie puts on gray bubble sunglasses. “Where’s the schedule, so I can see if I need another wakeup pill?” They check the guest list for a party that evening which will feature a Love Machine Cocktail—crème de cacao, vodka, and Pernod—and a Love Machine Cake decorated with two clasped hands like the jacket of the book. A publicity aide says, “May I suggest that you’ll get everyone sick if you serve that drink.” Irving says, “How about we put a Spanish fly in it, and have the rolls made up like phallic symbols? Ha ha ha. That’s funny, isn’t it?”

They arrive at the Shoreham Hotel, where the American Booksellers Association is holding its annual convention, minutes before a press conference has been scheduled for out-of-town newspapers. Jackie walks in with a demure smile. There are twenty men and women in the suite, and none smiles back. After a period of silence, Dan Green, publicity director for Simon and Schuster, asks the first question: “How does it feel to have another book on the best-seller list?” Jackie talks animatedly, perched on her chair. No one in the room takes any notes. A man in the back asks, “Do you read reviews?” Jackie says, “I’d like to have the critics like me, I’d like to have everybody like what I write. But when my book sells, I know people like the book. That’s the most important thing, because writing is communication.” Jackie describes her writing routine, Irving tells a joke at which no one laughs, even though he adds, “That’s funny, isn’t it?” At the end, Ivan Sandrof of the Worcester Massachusetts Telegram, says, “What do you think is the reason for everybody reading your book, apart from the obvious?”

“What’s the obvious reason?” Jackie says.

“Sex, pure and simple.”

Jackie says it is not sex that sells her books. “I’m a today writer. The novel today has to compete with television and the movies. It has to come alive quickly and be easy to read. When people tell you they couldn’t put the book down, that is good writing.”

“Jackie has succeeded where no one has before in tapping all the modem means of communication in one great campaign—movies, television, newspaper interviews, magazines, commercials, all cleverly bound together.”

The sex in Susann’s books is minimal by contemporary standards. Although a girl is undressed by page three, lovemaking is described only in vague terms. Instead of using naturalistic language, characters employ prudish euphemisms. Men refer to their sexual organs as “Charlie.” Women talk about getting “the curse” every month. Jackie says, “I can’t stand being clinical. You don’t have to say, then he took out his thing and put it in her vagina. For adults, all you have to say is, he took her in his arms.”

Susann writes sex not for the liberated woman but for the one with strong inhibitions. Most of the love in The Love Machine is joyless, violent, and cruel. Robin Stone, the central character, has to be drunk to make it with the actress Maggie Stewart, beats up a prostitute after taking her, and gets involved unknowingly with a transvestite. Amanda, the high-fashion model, goes to bed in a padded bra because she is flat, and later submits to a sweaty comedian who repulses her. A homely girl does “cold cream jobs” on celebrities who ignore her the next morning. This is the kind of sex which probably discourages going out and trying it.

Michael Korda, Jackie’s editor and the editor in chief of Simon and Schuster, feels Jackie’s promotability is the key to her success. Without promotion, he says, the book would probably sell 100,000 copies, “but it wouldn’t have the great impact it does.” Valley of the Dolls sold 356,000 in hard cover and ten million paperback. “Jackie has succeeded where no one has before in tapping all the modem means of communication in one great campaign—movies, television, newspaper interviews, magazines, commercials, all cleverly bound together. Most novelists are not promotable. They don’t go on tours because they wouldn’t know what to do.”

Irving says, “Jackie and I have probably changed the whole book publishing business. For one thing, usually the publisher has a little cocktail party in a dingy restaurant with stale lettuce sandwiches when the book comes out. We had a big swing at El Morocco and we invited everybody—Andy WarhoI, Perle Mesta, Also, we sold the paperback rights before we sold the hardcover rights.” The film rights were purchased for a record sum of one and a half million dollars.

In the Eastern half of the country, critics and interviewers approach Jackie with condescension. Jackie says, “They walk in with the attitude—how dare you be a best seller.” A television reporter in Washington said, “Are you pleased with what you’re leaving behind you in life?” A Detroit newspaperman read Jackie a review which called her writing “trash” and said, “How does that make you feel?” During a Toronto television show, a young woman said, “Don’t you ever wake up in the middle of the night and realize you haven’t done anything that is really artistic?” Jackie said, “You’re sick. Do you wake up and think you’re not Huntley-Brinkley?”

Once she has crossed the Continental Divide, and especially in Los Angeles, the feeling toward Jackie changes. Reporters gush at her, and Susann is called America’s best writer. One man told her his wife had started referring to his sexual organ as “Charlie.” “You’re adding words to our language.”

Jackie is almost uninsultable. A snide question, a bitchy interview, brings out the best in her. She reads vicious reviews and grins, “I think it’ll sell a lot of books.” On the David Frost show, critic John Simon asked Jackie in his echt Central European accent, “Do you think you are writing art or are you writing trash to make a lot of money?” Jackie lurched forward and threw a torrent of ad hominems at Simon: “Is your name Goebbels—you act like a storm trooper.” She called him “Simple Simon,” a joker, a publicity hound—“How many people have even heard of you?”—all the while Simon kept shouting, “That’s not important. Will you just answer the question. What do you think you are writing?” Jackie tried another tangent, saying Simon was “rather nice looking” even though his hair was thin. Simon said, “Cut out all this soft soap. I can smile through my false teeth like you.” Jackie bared her teeth and hit them with her finger. “Look, they’re caps, not false.” Simon kept pressing. Jackie finally said, “Little man, I am telling a story. Now does that make you happy, huh?”

Usually, Jackie succeeds in debilitating her opponents. She watched a young man preparing to have a go at her on Panorama, a Washington television show, sitting on his white toadstool chair picking his teeth. “Don’t do that,” Jackie said, “you’ll hurt your teeth.” Later, she gloated. “That reduced him to a little boy.”

(Jackie is one of those women, like the late Judy Garland, Bette Davis, Edith Piaf, and critic Judith Crist, who are beloved by homosexuals. In Jackie’s case, it is due not only to her strident personality but to the fact that she treats homosexuals with dignity in her books.)

In her travels from city to city, the one publicity tool Jackie has given up is the autograph party. “When you appear at a bookstore, you are at the mercy of any sex maniac who gets in line. They can say, ‘Wanna fuck, baby?’” While promoting Valley of the Dolls, Jackie says, “Beastly weirdos would come up and say, ‘Wanna go to a pot party?’” Irving says, “They’ve said the worst things. I’ve had to acquire the sixth sense of a T-man. In a Detroit bookstore, three guys were standing in a corner. They were daring a friend to go up to Jackie and say; ‘Your book stinks.’ I spotted it a mile off.”

Jackie accepts interviews from all publications, all media, no matter how small or limited their reach, unless she or Irving suspects the writer is out to do a hatchet job. She turned down The Village Voice, columnist Dick Schaap, and Saturday Review. “I tried to turn you down,” Jackie told me. For months, she will give six or more interviews a day, repeating the same stories with unfailing enthusiasm.

“Never in the history of the world has there been a writer with this charisma.”

At the American Booksellers Association in Washington, Jackie has set aside an hour and a half for William Silverman of the Detroit News, who is writing a cover story for his newspaper’s Sunday magazine. He asks Jackie to pose for photographs. “I want something that’s sexy and glamorous, but I don’t want it to be vulgar.” Jackie says, “That’s marvelous.” Irving shakes his head. “The problem is, this is not a glamorous background. There’s no satin, there’s no damask.” Silverman, a grandfather in his sixties who has the shape of a large panda bear, drops to the rug and lies on his stomach, kicking one foot up and, resting his chin on his hand. “Could you be like this, like you were writing?” Jackie obliges, adding, “You know, I write like this every day.” Irving dozes for a while, awakens with a smile and sings, “If you can talk to the animals.” Silverman is asking Jackie how her success has affected her marriage. “When people work with each other, not in competition but together,” she says, “it’s like a dance team.” She jumps up and strikes an arabesque with her white-stockinged legs. “You could say Irving and I are Nureyev and Fonteyn.” She waves her arms in gawky ballet gestures. “We are the Burtons. We are anything that is two people working together.”

When she turns aside, Silverman says to me, “Do you believe that?”

Dan Green interrupts the interview to tell Jackie people are crowded around the Simon and Schuster booth in the exhibit hall, where she is scheduled to autograph copies of her book. Because of a feeble air-conditioning system, the hall is steaming hot, with thin red carpets and silver tinsel hanging from the ceiling. A double line radiates out from the alcove where Jackie is seated. The lines completely block access to the displays of Harper & Row, the New York Graphic Society, Fleet Press Corporation, and Bantam Books. Irving says, “Never in the history of the world has there been a writer with this charisma.” Jerry Kramer of the Green Bay Packers, Lillian Gish, Kurt Vonnegut, Jr., and Tiny Tim also appeared to plug their books but drew scant attention compared to Jackie. The people in line—bookstore owners, salesmen, jobbers, editors, publishing executives, and some reviewers who sat stony-faced during Jackie’s morning press conference—wait for more than two hours, clutching yellow pieces of paper on which they have printed their names so Jackie can write personal messages. “For Isabel Smith. All my best.”

One of the first in line is Lloyd Severe, a supervisor at Martindale’s bookstore in Beverly Hills. “Frankly, this is not exactly my type of book, but my wife wants it.” Asked what accounts for Susann’s popularity, the tall, bald man stretches his lips into a smile. His eyes twinkle behind rimless glasses. “There’s only one word for it. People like thrills.”

Irving, in his yellow, green, and pink Pucci tie and Gucci shoes, never moves more than a few feet from Jackie. He sings, “If we could talk to the animals.”

When Jackie leaves the floor, the Simon and Schuster group say they have given away six hundred books. When they arrive at the suite, the figure has grown to eight hundred. That evening it is one thousand. A bottle of champagne is brought to the room. Michael Korda, a wiry British blond who wears a bright-blue suit with red stitching, a red handkerchief, a black belt with gold metal studs, a blue wide-striped shirt, and blue motorcycle glasses, walks in and kisses Jackie on both cheeks. “Do you think we’ll make number one?” she says softly. “Of course we will,” Korda says. Jackie drinks the champagne in a water glass with ice cubes. Irving makes the toast: “To the first author who’s gonna be back-to-back number one on the best-seller list.”

In the Chatelaine Room of the Mayflower Hotel, fifty bookstore owners, managers, and buyers from department stores have bypassed the Love Machine Cocktail for whiskey or gin. Since publication of her first book, a biography of her poodle called Every Night, Josephine!, Jackie has cultivated friendships with booksellers. She considers some of them among her best friends.

A shout goes up when Jackie appears at the party in a turquoise voile dress. A strawberry blonde book buyer from Oregon grabs her arm and pumps it. “I want to shake the hand of the lady that’s been makin’ me so much money the past two years.” The book buyer, an angular, freckled woman, in a black chiffon dress with ruffles around the scooped neck, says she doesn’t think Love Machine will sell as well as Valley of the Dolls because “it’s an over-again, the same jenner. (Genre?) It’s Jackie’s husband that puts her across with all that Madison Avenue hoopla, and I love it! The pa-toy they speak! (Patois?) It’s just marvelous. I don’t care what’s in the book as long as it sells.”

Irving and Jackie move to a different table for each course—crab cocktail, vichyssoise, beef en brochette, wine and cake. When the Love Machine Cake is wheeled out with seven candles, Jackie carries it around the room. “For a finale, I fall into it.” She and Irving leave just before 10:00 P.M. to catch the last shuttle back to New York. As they settle in the limousine, Irving swivels around. “Jackie, will you stop already with these goddamn books! Ha ha. That’s funny, isn’t it?”

The Mansfields live in a three-room apartment in the Navarro Hotel overlooking Central Park South. The decor is theatrical, with black lamp bases in the shape of human torsos, red shades, ivory linoleum floors, and a large bar. The walls are lined with photographs of Jackie with celebrities, Irving with celebrities, and celebrities who have appeared on television shows Irving has produced. On a late Friday afternoon, just before leaving for California, Jackie is having caviar and imported Russian vodka, straight, with her press agent for The Love Machine, Abby Hirsch, a fashion-conscious young woman who radiates self-assurance and efficiency. Abby’s salary is paid by Simon and Schuster, which guaranteed to spend $75,000 promoting the book, and has spent considerably more.

The Love Machine dominates Simon and Schuster this year. In the reception hall, red and white buttons with the book’s title are pinned to the rubber-tree plants. Michael Korda has written on the walls of his office in blue ink: “Three bottles of Dom Perignon, ’59 or ’61, The Love Machine—50,000 advance. Sixteen ounces of caviar when we reach number one.” There are bets recorded as to when the book would hit the top spot. Korda says the advertising budget for Love Machine is larger than for any book they have published. In addition to Abby, they use a press agent in California, Jay Allen, and a full-time press agent in New York, paid for by Irving.

“Nothing is as dull as a woman without a past. And once you know all the details there is no past. Just a long, dreary confessional.”

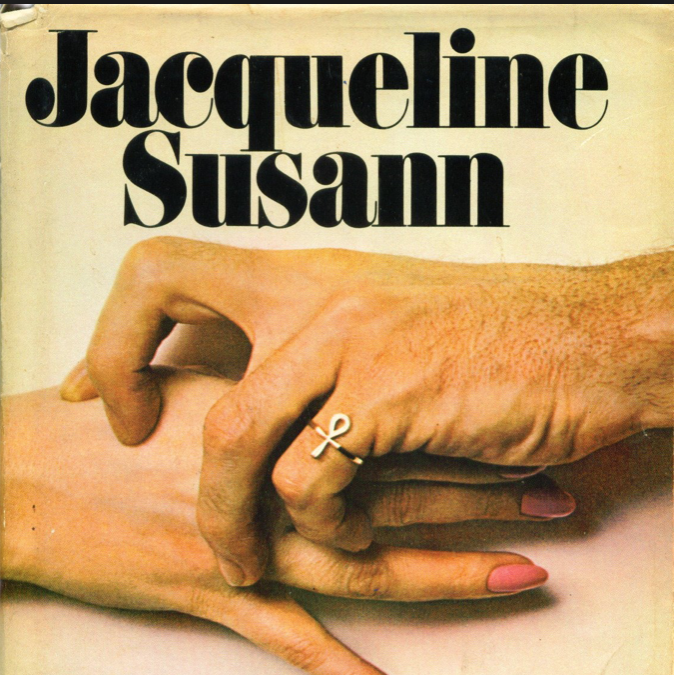

Both Abby and Michael Korda, like Jackie, wear around their necks a gold chain with the ankh, an Egyptian symbol of life, which Jackie made the motif of The Love Machine. She first saw it on Janet Leigh, wearing it in the form of a ring at a party. Janet Leigh gave the ring to Jackie, who had her jeweler make it up into necklaces. She has presented these large gold crosses with a loop on top to John Lennon, the Beatle; to Muriel Slatkin, daughter of the owner of the Beverly Hills Hotel; and, among others, to me. On television, Jackie likes to describe how Cleopatra carried the ankh as a symbol of eternal sex. But it is not Cleopatra of the Nile she conjures up; it is Cleopatra of Twentieth Century Fox. Two New York designers have started production of ankh necklaces, pins, wrist and ankle bracelets, and there is talk of a Love Machine perfume. The Mansfields have avoided these projects. “It’s a little too much,” Irving says. “Jackie’s a writer, an artist. Inside this little breast beats a heart that is not as commercial as people think.”

The Mansfields’ lifestyle has not changed since they struck gold in publishing, because they have always lived conspicuously well. They commute between Central Park South and the Beverly Hills Hotel, where they have had the same suite—at $78 a day—since 1959. Jackie does not cook. In Los Angeles they dine at Chasen’s, in New York at Sardi’s, Danny’s Hide-a-way, “21,” and, if they are feeling informal, P. J. Clarke’s. They are city animals and have no desire for a yacht or a country estate. On Sundays in New York, they like to walk to the out-of-town newspaper stand in Times Square, have breakfast at Nathan’s—two dozen cherrystones for Jackie, two hot dogs for Irving—and go to a movie like The Green Slime.

Like the characters Jackie has created in her books, she and Irving seem to be rootless, tieless. Jackie writes in The Love Machine: “Nothing is as dull as a woman without a past. And once you know all the details there is no past. Just a long, dreary confessional.” Jackie and Irving have sealed off their own past with vague and contradictory references. Jackie often says she was born in 1963, the year her first book was published. When a reporter asked her age, Jackie said, “You could say I’m a young woman in her thirties.” The reporter looked up. Jackie smiled. “Newsweek printed my age—it’s forty-two.” Jackie looks younger than forty-two; her figure is slim and her hairpieces are set in youthful, shoulder-length flips.

I accepted the age of forty-two until I met an actress at a party who said she remembered Jackie from the theater in the late 1930s. When I called other theatrical figures, I found they were reluctant if not terrified to talk of Jackie’s past. One woman said, “Jackie will be furious if this gets out. She doesn’t want the country to know she’s been around all that while. She doesn’t want to shock the country. If I looked as well as she does, I’d be proud. I’d want everyone to know how old I was.”

Programs on file in the Lincoln Center Performing Arts Library show that Jackie appeared in Max Cordon’s production of Clare Boothe’s The Women in 1937, in She Gave Him All She Had, and When We Are Married in 1939; in My Fair Ladies, and Banjo Eyes with Eddie Cantor in 1941, and in Jackpot in 1944. She was not playing child roles. As the reluctant actress put it, “You can’t put two and two together and get forty-two.”

A subject Jackie and Irving never bring up is their son. When questioned, they say the boy is sixteen and in school in Arizona. In Jackie’s novels there are no children (except for an occasional infant), no families living and growing up together. She creates a dream world of stardom, money, and power where personal ambition and lust are the only forces. The hero of The Love Machine, Robin Stone, blazes his way from delivering news on a local television station to controlling the national network. In the process, he is loved by, without loving, a breathtaking, breast-less model, a voluptuous actress, and the blue-blooded wife of the chairman of the network. Although the story is set in the 1960s, there is no mention of Vietnam, the generation gap, racial tensions, urban riots, inflation. The book, like Valley of the Dolls, is an escape hatch from the news. It shoots the reader to a fantasyland where there are no babysitters, no commuter trains, no supermarkets, but at the end of the trip, the reader is psychologically prepared to get off, reassured that there is no place like his double-mortgaged home.

Susann’s characters experience no guilt about sex or anything that might be considered “sin” in the Judeo-Christian tradition. When a girl loses her virginity, or a baby through abortion, she gives it no more thought than if she had lost a tooth. The relationships traced are not marriages but love affairs. Because all the characters have miserable, bathetic fates, the mainline American family can feel its own values have been upheld.

A young man with green eyes and an easy smile is sitting on the cream-colored couch in Jackie’s suite at the Beverly Hills Hotel. “I saw a lot of myself in Robin Stone,” he says. Irving says, “So did Peter Lawford.” The young man, in a voice that has no distinguishing inflection, says, “I’ve learned to hide my feelings and not show emotions ever since I was little.” He turns on a tape recorder. “This is Dick Spangler. My guest on The Forum is Jacqueline Susann. Miss Susann, you’ve been criticized as not being the best writer, although you are the best-selling writer.” Jackie says, “Way back they didn’t think Shakespeare was a good writer. He was the soap opera king of his day. They called Zola a bad writer, a journalistic writer. Everything changes in writing. I think James Joyce is a bore. Ulysses is a bore. In fiction today there is no time to do great exposition on a landscape. Writers like Harold Robbins, Leon Uris, and Irving Wallace have given the novel new life, new excitement. They’re storytellers. That’s the place for the novel today.”

Breakfast is brought in on a gold tray. Jackie drinks iced tea and cuts off pieces of a kosher salami she was given by a television sponsor. She removes the butter from the tray and puts it in her icebox. Irving says, “Would you believe it? A woman as rich as Jackie stealing butter?”

The Beverly Hills Hotel is an island of New York theatrical people transplanted to the glades of Southern California. The building with its pink cupolas rises from a slope of palm trees. From the sliding glass doors of their suite, Jackie and Irving look out on a red-tile patio with rows of geraniums, a green picket fence, and green garden furniture. In the distance, the yellow and white cabanas of the pool stand out from the hibiscus and coconut palms. Through most of June, the landscape is muted by gray haze.

The inescapable fact about Jacqueline Susann is that even those who denounce her have probably read Valley of the Dolls.

Jackie and Irving have been in Beverly Hills for two weeks, visiting bookstores in Monrovia, Pasadena, and Westwood. Jackie has appeared on more than 39 radio and television shows, including a week on the midmorning game show, Hollywood Squares. She has been on television more hours in the past two years than most actors. The only show that has turned her down is Art Linkletter. For Hollywood Squares, she is driven to the NBC studios in Burbank with five costume changes, since a week’s worth of programs are to be taped in one night. In the back of the studio, the stars—Wally Cox, Shirley Jones, Jack Cassidy, Vincent Price—pop in and out of their dressing rooms as if they were playing a slapstick comedy.

“Hey, Vince.”

“I just bought a house on the beach.”

“Look at my new dog.”

On the set, the warm-up man, burly, red-faced, with dandruff on his shoulders, bellows at the audience, “Hello, my name is Ken Williams. I’m from Baltimore. Where are you all from?”

“Eddyville, Iowa.” “Mayville, Tennessee.” “Mt. Eric, North Carolina.” This is Jacqueline Susann country.

Peter Marshall, the emcee, introduces Jackie. “You ladies know all about this guest. She wrote Valley of the Dolls, which sold a couple books, and The Love Machine, which just knocked Portnoy’s Complaint off number one on the best-seller list. Which shows, if you write family, beautiful, sweet things, you’re gonna make a buck.” The audience is cued to laugh. The game is played like ticktacktoe. Each star sits in a separate box of a large orange steel contraption. Two contestants try to earn boxes by picking a star, listening to the star answer a question posed by the emcee, and then deciding whether the star is right. If the contestant is right, he gets the box. The first to win three in a row gets $200 in cash, and possibly luggage, a car, a vacation, or a mink coat. The contestants, chosen from the audience, are all young, bubbly, not overly bright, with no long hair, even on the girls.

There is one black girl, but she is the antithesis of the Afro look. She could be a model for Breck shampoo. A large portion of the questions are based on articles in Ladies’ Home Journal and Woman’s Day. Jackie is asked what Benjamin Franklin used as his pen name for Poor Richard’s Almanac: Richard Benjamin, Richard Small, or Richard Saunders. Jackie says, “I’m going to guess—Richard Saunders.” The contestant says Jackie is wrong. Jackie squeals when told Richard Saunders is right. “You should have trusted me,” she says to the contestant. “One writer with another.” On the last show, when Jackie is introduced in her blinking orange box, she mouths the words, “Hello mother.” Mrs. Susann watches the program every morning in Philadelphia.

They finish just after 11:00 P.M., and the producers, directors, and several of the stars drive to the home of Mary Markham, an independent producer and talent coordinator, on Beverly Drive. It is a lavish house of excessive symmetry. There is a fake fire blazing in the den, where Jack Cassidy is playing pool. Mary’s dog, a white animal she says is a “cockapoo—a cross between a cocker spaniel and a poodle,” is lurching through the house bumping into furniture. Three men begin playing a dice game called “Canoga” over the long, sunken bar. Jackie is the first of the women to join, throwing dollar bills into the pile. She wins the first two games, and claims the cash pot with a cold smile. Irving sits on the couch saying, “No, no!” as the cockapoo laps at his face. Cassidy confides in Jackie that he wants to write a book. Jackie says, “You should. I think any good actor is a good writer, because he is able to mimic life.”

Jacqueline sets many scenes of The Love Machine in the pink and green Polo Lounge of the Beverly Hills Hotel. During the day, the theatrical crowd, who greet each other with cries of “Marvelous,” pronounced “mah-velous,” is filled out with wealthy women whose daughters are always married in the hotel’s grand ballroom. In the ladies’ lounge, a blonde girl who looks to be nineteen is curled on a couch, sucking her thumb. Her mother is stroking the girl. “I’ve ordered those nice chicken pancakes. We don’t want them to get cold.”

In the Polo Lounge, Jackie is seated on a green banquette in front of a trellis with plastic ivy. She has been giving interviews for several hours, and is eating a hamburger and a glass of water as part of her meat and water diet, which she describes in detail to each reporter. She devotes an hour to People Today magazine, another to the Long Beach Independent-Press-Telegram, and then sees a young reporter from the Los Angeles Herald Examiner. When asked if she expected her books to be so successful, Jackie says, “I came up the hard way in acting, so with writing, I was going to start right at the top. I had always written for myself—stories, poems, I had a play produced on Broadway (Lovely Me in 1945). When I saw people reading my first book, Josephine, I would think, there’s someone reading the baby. When I saw people reading Valley, I would think, they have very good taste.”

In the evening, Jackie is a guest on the Steve Allen Show, taped in the Hollywood Video Center on Vine Street. The sidewalk of Vine, like that of Hollywood Boulevard, is pink inlaid with gold stars bearing the names of actors. Jackie is shown to a spartan dressing room with a couch and a director’s chair. A young man with a beard walks in and asks her to sign a release. Looking at herself in the mirror, combing the Korean hair, she says, “Is this an AFTRA contract?” The young man frowns, “I’m an AFTRA actress. I don’t go on a show without getting paid.”

Jackie and Irving watch the beginning of the program on a monitor. “It’s the Steve Allen Show, with Jacqueline Susann….” A stagehand comes for Jackie. She stands, pulls up her white stockings, straightens her Pucci dress, and waves, “See ya.” When she appears on the monitor, Irving says, “She’s just radiant, isn’t she? Even when the show is terrible.” Steve Allen invites members of the audience to ask Jackie questions. As on all her West Coast radio and television appearances, the audience asks how she learned to write, what is her technique. What they mean is: If you can do it, why can’t I? Jackie says her father, a portrait painter, taught her to study people’s faces and voices. She does some sloppy imitations of Zsa Zsa Gabor and Tallulah Bankhead. Jackie is asked to play a running-jumping game with a girl swimming champion and a black comedian. After she hears the rules, she says, “I’ll watch.”

As the show ends, Bob Shayne, the twenty-eight-year-old talent coordinator, says to me, “I hope you’re not going to be as kind to her as we were. We had no intention of giving her such a plug. We had review sheets all ready for Steve. We were dying to plant someone in the audience to ask a leading question. I read the other book she wrote. She can NOT write.”

The inescapable fact about Jacqueline Susann is that even those who denounce her have probably read Valley of the Dolls. According to statistics kept by Publishers’ Weekly, more people have bought that novel than any other published in America in the twentieth century. She is a national phenomenon, and we are stuck with her. There is a built-in audience of ten million for every book she turns out. She is as compulsive about writing as the legendary British popular novelist who kept a rigid schedule of writing five hours every day. If during that time he finished a novel, he would type, “end,” insert a new page and type the title of the next book. Jackie has already written a first draft of a new novel to be called The Big Man, about a girl with a dominating, magnetic father. She writes the first draft in the period between the time she finishes a novel and the day it is published and she embarks on the promotion tour. “Then I don’t return to an empty typewriter.”

Even after the film rights of The Love Machine were sold for a million and a half dollars, even after the book had hit number one, Jackie continued to plug it as if she were an unknown author. “Maybe it’s my bag, but I feel I have to keep going around and doing it,” She was autographing books for Higbee’s in Cleveland when she learned Love Machine had made number one. Her immediate response was, “We’ve gotta keep it up there.” Irving says that with Jackie, staying number one is a matter of pride. “Simon and Schuster wanted us to hold off publication for a month because Portnoy’s Complaint was so hot. But Jackie said no. She wanted the title shot. She’s a natural going competitor.”

Irving has taped on the wall of their creamy bathroom in the Beverly Hills Hotel a cardboard facsimile of the New York Times Best Seller List of June 22, the first week Love Machine was number one. “It’s great to watch when you’re on the head,” Jackie says. “It makes you relax. It’s good for the soul.”

Irving looks up from his copy of Variety. “That’s funny, isn’t it?”