It is a hot Los Angeles afternoon, sun beating down on the city, burning through the blanket of thick, brown smog lying on top of the basin. But here on Sunset Plaza Drive where Jim Brown’s house sits at the highest point of this rise, the air is clear. Brown’s house with its spectacular 180-degree view—from the downtown skyscrapers to the East, to the beaches of Santa Monica to the West—is a common note in articles about Jim Brown. Interviews are conducted right here. “You are in my home,” he says. “That puts you at a disadvantage.”

Even now, 21 years later, still looking for the edge.

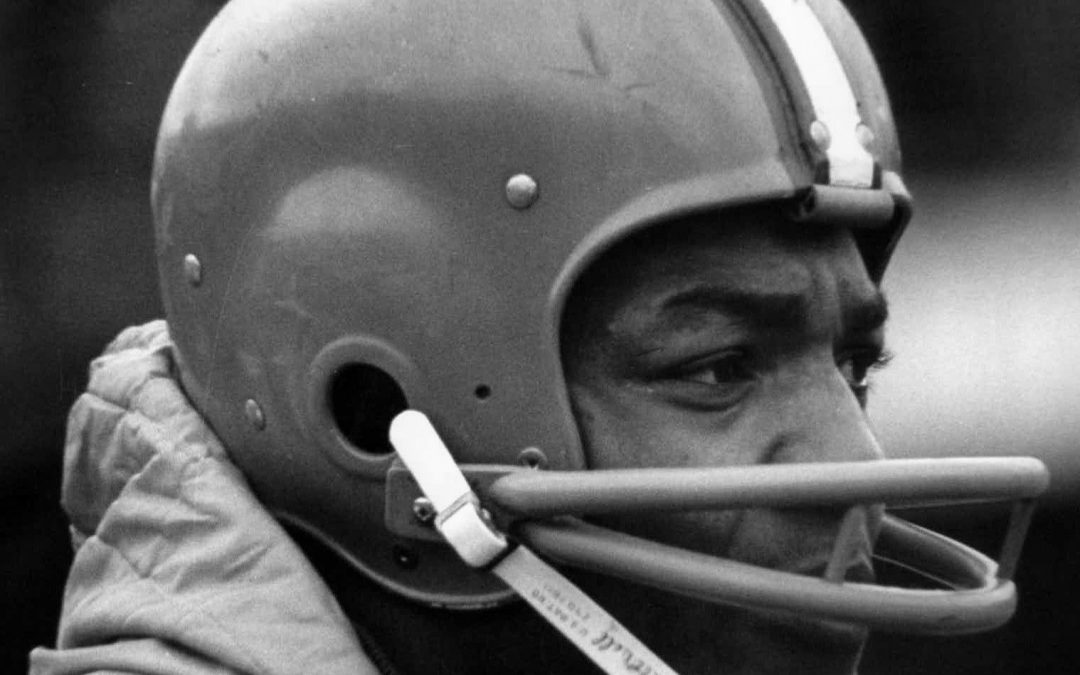

For nine seasons from 1957, his first year with the Cleveland Browns, through 1965, when he abruptly retired, Brown played football exactly the way he wanted to. If he disagreed with the calisthenics his coaches prescribed, he didn’t do them. If he believed he knew the game better than his head coach, he gave his lineman his own set of instructions. “If I score a touchdown,” he would tell them, “nobody will care. If I don’t, I’ll take the heat.”

No other running back has come close to duplicating his accomplishments. Certainly nobody has matched his 5.2 yards per carry, or his average 104.3 yards per game. And though Walter Payton has surpassed Brown’s career yardage (12,312) it took him 18 more games to do it. Starting this season, he still lagged behind Brown in touchdowns scored, 126-109.

When Brown left the game, that too was on his own terms—age 30, to become a movie star. “I don’t want you to think I didn’t enjoy the sport,” he says. “I just understood it for what it was.”

Since then, he has played the rest of his life by the same rules, calling his own shots, as much as any man can. “I have an option,” he says in a rather long-winded speech, “I’ve always had an option, you must understand. If I became a pawn of society and said the things I was supposed to say as most of your superstars do today, I would be rich and I would be given false popularity.

“But when history comes down, that ain’t nothing. I am a free man within a society. I love that. I love that over money, over being popular. I don’t want to be Michael Jackson. Whew, I wouldn’t trade places with Michael for a million dollars. I don’t think Michael knows what he’s doing. I think he’s lost. I don’t think he has a point of view, you know? I think you have to have a point of view.”

It is an odd remark, in light of whom he has chosen to compare himself to. But figuring Brown’s mind is like trying to figure his next move with the ball. “What I’m saying,” he concludes, “is I just want to be normal.”

He has a looming presence. Though he will deny that he was, or is today, an angry man, the sight of him as a player fueled that belief. Six-feet-two, 230 pounds, a body of rolled steel, a dark and expressionless face, chiseled to show the hard edges, his features seem to proclaim that no matter what, this man stands alone.

The size and the muscle are still there. And when you rise up to greet him, and reach for his outstretched hand, glimpse the polite smile, you are aware only of a deep sense of disquiet. He is a different man.

He has arrived late for this appointment, hurrying in the front door with a pretty doll-like girl trailing behind. Both look slightly damp. He is wearing black nylon shorts and a matching windbreaker zipped halfway up. There is no shirt underneath. The two have just finished their daily workout at the Sports Connection in West Hollywood, where Brown first encountered her months before when she was working as the club receptionist.

“Meet Debra,” he says and disappears.

Debra Clark in her tights, all 90 pounds of her, looks like a stick figure, though obviously superbly conditioned. Her long, thick, black hair is pulled back in a ponytail to show off a startlingly beautiful face. She will turn 22 the following week but looks no more than 15. Later, Brown gruffly concedes he will probably marry her, “in the next few months,” praising her as “extremely bright and sensitive.” But when he is asked how she spells her first name, he shrugs and yells, “Hey, Deb! How do you spell your name?”

Ten days later Debra’s name is spelled out in newspapers across the country. In the middle of the night, Debra phoned the police for help, having locked herself in a bedroom at Brown’s home, armed with a .44-caliber revolver. According to Clark, Brown had been drinking and accused her of having paid too much attention to male patrons at the Sports Connection earlier that day. She said Brown had pummeled and kicked her in a jealous rage.

“It’s very simple,” he says. “I don’t like inequities. I don’t like being a second-class citizen. I want to be a full part of any society I live in. So that’s always going to drive me. The fact that I’m black in a white society.”

Clark, who wound up with a scratch under one eye, a bruised arm and a possible cracked rib, identified herself as Brown’s fiancee and said they had planned to be married the following day, her birthday. Brown was arrested at his home and spent three hours in jail until he was able to post $5,000 bail and was released. Three days later, Clark walked into the Hollywood police station and said she did not want to press charges.

Brown himself had little to say about it. “Being who I am, one telephone call creates a thing across the country,” he said over the phone one night in soft, mellow tones. “As a people event, it was nothing. As a media event it was something else.”

But surely, he was told, something had happened; Debra had felt compelled to phone the police. “It’s the fear that goes on in minds because of me,” he said. “I am not going to give a defense. We are still living our lives.”

With that, he put Debra on the phone. “Hello,” said a small voice. Brown took the phone back and laughed. “I don’t know what that proved,” he said. “That voice could have been anybody’s.”

Asked if he had a quick temper, Brown replied, “I’m probably a very patient person in most cases.”

Brown has been in the news frequently since he left the football field. In 1965 he was accused by an 18-year-old girl of slapping her and forcing her to have sex. He was found innocent.

Four years later he was accused of assaulting a West Hollywood man after a minor traffic accident. He was acquitted. He was not acquitted of beating up a golf partner during an argument over placement of a ball on the green. He was fined $500 and served a day in jail.

Then, 22 months ago, in a sensationalized and widely publicized case, a schoolteacher who was a friend claimed Brown beat and raped her when she refused to engage in sex with him and another woman. “What exactly happened in that last case?” I asked him at his house.

“You must have read about it in the papers,” he replied, looking amused, “or I don’t think you would have come here.”

Although the woman had clearly been beaten, the charges of rape, sexual battery and assault were dismissed after the teacher gave confused and inconsistent testimony.

“I’m very vulnerable,” Jim Brown said. “I don’t have much chance if someone wants to get me.”

Brown presents himself as hardened to the realities of life, but he seems as sensitive as a wallflower to any perceived slight. He is often imagined as a man filled with a private inner fury, the way he played, the way he quit, the way he lives; consider his scrapes with the law. But Brown just laughs and says of anyone who thinks that, “Maybe your mentality wouldn’t be high enough to conceive what I am saying.”

He is sitting by his pool, protected by the shade of an umbrella poking out of a round glass table, leaning back in his chair. There is a silence. Brown waits, amused. He has been through this before. Okay, if not anger, then what?

“It’s very simple,” he says. “I don’t like inequities. I don’t like being a second-class citizen. I want to be a full part of any society I live in. So that’s always going to drive me. The fact that I’m black in a white society.”

Only Brown, of course, knows the racial trouble he’s seen. But more than most black youngsters growing up, he was offered the advantages of privileged white society. He spent the first eight years of his life in St. Simons, Georgia, under the care of his great-grandmother and his grandmother. His mother sent for him then, and brought him to the well-to-do community of Manhasset, Long Island, New York, where she worked as a cleaning woman.

Brown offers two conflicting views on life in Manhasset. On the one hand he says, “I had to deal with racism ever since I was born. Sports was an area that was more progressive than others. You never could have been a nuclear scientist because grade-school teachers would say don’t even bother taking those kinds of courses ’cause they’re not going to do you any good anyway. So what I had to do was set a standard that was a little higher.”

On the other hand, he says, “At Manhasset everything that was done for me is why I’m here now. I was taught about education, I was taught about fairness, given a chance to excel, encouraged to run for student-body president. I was given a confidence that I ordinarily wouldn’t have had. These people were the finest people I ever met in my life.”

Brown so excelled he received 40 scholarship offers from colleges. And here he ran into problems. At Manhasset he had come under the paternal eye of a group of local boosters, including a lawyer named Ken Molloy. Molloy wanted Brown to go to his alma mater, Syracuse, but Syracuse had shown no interest in Brown. So Molloy, unknown to Brown, raised enough money to finance his first year, after securing the school’s unenthusiastic word that, yes, if Brown were that good, a scholarship might later be made available.

“At the time Syracuse didn’t want any black athletes up there,” says Molloy, now a New York State Supreme Court justice. “But I didn’t know that. I put the kid in the mouth of a cannon.”

The enigma of Jim Brown is compounded by a side of him that receives far less publicity than his run-ins with the law.

Brown vividly remembers that first year. “They tried everything they could to discourage me,” he says. “I had to just fight. Hard. Probably an observer would see that and say this guy is angry. But all I was doing was fighting to overcome the cynicism and the doubts and the tests and intimidation that were put on me.”

Brown wanted to quit. But Ray Collins, the superintendent from Manhasset High, drove to Syracuse and persuaded him to stay. “It was the only time I doubted myself in my life,” Brown says. “And they almost had me. But when I stayed, and went from fifth-string to all-American, I said to myself never again in my life will I let anybody tell me what I can’t do. And that was the start of a certain attitude. But it was close.”

There is always the sense around Brown that you are dealing with a sleeping lion, that at any moment the most careless gesture might wake him up. And his wrath. Brown carries with him an element of intimidation, invisible yet palpable, as if he were armed and ready to explode. It was this emotional fission that ran him into the end zone and, at times, afoul of the law, but never once in anyone’s memory did he lose control of it on a field of play. On that field, Brown kept a steely hold on his emotions.

“He was always a gentleman,” says Sam Huff, the fabled Giant linebacker. “No matter how hard I hit him. In fact, on an especially good tackle, he would often compliment me.”

Molloy remembers a lacrosse game at Syracuse during which an opposing player baited Brown with racial epithets. Brown did not respond. “A lot of teams tried to get Jimmy enraged, hoping to provoke a fight as a ploy to get him thrown out of the game,” Molloy says. “I never once saw him lose his cool.”

But off the field he was never so predictable. One of Brown’s longtime friends, contacted for an interview, says, “I don’t know. It would make me nervous. I might say something that would offend Jim, without my meaning to. Frankly, I’ve always had this insecurity with him.”

“Daddy, will you fix my bike?” four-year-old Kimberly snuggles up to her dad. Brown’s only marriage produced three children, none of whom he is close to. “You feel funny going back,” he says. Kimberly came along when he was living with her mother, Kim Jones, a young black woman whom he met roller skating at Venice Beach. Brown says that after the split with Kim, he was not allowed to see his daughter for two years. Then last December she was brought to the house; she has been there ever since.

“Her mother’s now filing for custody or something,” Brown says. “She said I took Kim out of school. She lied and said I stole Kim. But how can you steal someone when your phone number hasn’t changed since 1968, the address is the same and she’s here?” He pauses. “My front door is generally open.”

He says this with resignation. Not everybody is going to play by the inflexible rules he has set for himself. “What stands out about Jim is his highly tuned sense of fairness,” Ken Molloy says. “He’s made a fine art of it. And this I think is what precipitates a lot of other things. He’s like a cat in a jungle, always looking for things.”

“Oh, that Walter,” says Brown with a smile. “You watch the heart of Payton. The heart is unbelievable. But Walter couldn’t jump in my face right now and throw me off the balcony.”

If this is Brown’s failing—an honorable, honest man making his way in a dishonest world, as he would seem to have you believe—it is offset by an even greater failing: his history of lashing out at victims who have done him wrong. Whatever the circumstances of those cases recorded on police blotters, women have borne the bruises and, at least publicly, Brown never expresses regret or suggests that maybe he was out of line. When speaking of the Debra incident, all he musters is indignation that “The police had a helicopter circling over my house, can you imagine?”

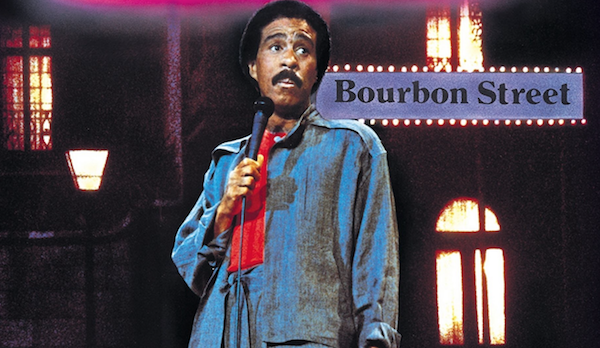

Jim Brown’s vision of how things must be was also violated by his once close friend Richard Pryor. “Richard fooled me,” Brown says. “I’d known him as a person who would come into his life, usually when he was in trouble. I was foolish enough to think he really cared about me.”

Brown maintains he was trying to get Pryor into a hospital shortly before the comedian accidentally set himself on fire while free-basing cocaine. “At the time he had hired detectives to check on what his wife was doing, he was free-basing, he had guns around. I almost got him in the hospital, but he didn’t show up. And I think that very night was when he lit himself. He called for me in the hospital.”

Brown says he took over Pryor’s affairs. “People wanted the combination to his safe, I kept that from happening. With his feeble hand I got him to write a check so his family could have money for the house. I worked closely with the doctors. I kept one of his daughters at my house I dealt with all of his ex-wives, I mean everything you could think of.”

Nor long after his recovery, Pryor started a film company, Indigo Productions, funded by Columbia Pictures and Pryor asked Brown to run it. They made one film, Richard Pryor; Here and Now, and then according to Brown, Pryor went off to Africa. “When he came back, he said he wanted his company back. He said, ‘If you’re here, I won’t be here.’ So I just got my little stuff and left. He wrote me a strange letter. Said something about ‘differences of opinion, but if you ever need me…’” Brown’s voice trails off and he laughs.

“I feel sadness. There’s no animosity,” he says. “See, I never depend on anybody anyway. I thought Richard cared about me. But he didn’t care about anybody else. I knew he didn’t care about his kids, I knew he didn’t care about his wife. I knew he didn’t care about anybody. But, shit, he suckered me.”

When contacted for this article, Pryor would only issue a statement saying, “Jim Brown without a doubt was the greatest football player ever in life. Other than that I do not wish to comment on anything he said about me or Indigo.”

But in an interview with Essence magazine last spring, Pryor said, “He was a bully. And there was a point when I had to say, ‘All you can do is kill me, but you can’t be the president of my company, because I’m not going to take anymore of this shit.’ I got his nurse out of the sand—financially, anyway—a piece of money, $400,000. That ain’t chicken feed, you know.”

Today Brown is trying to start his own film production company that would make low-budget movies aimed at the black market. “You very seldom see anything in the movies about black people that’s across the board,” he says. “You never see the rich ones, the educated ones, the poor ones, we only see the ones who are crying the blues or singin’ and dancin’.” At the moment, he is getting ready to direct a movie called Slam Dunk, which, he says, “is like Romeo and Juliet for rich blacks.”

The enigma of Jim Brown is compounded by a side of him that receives far less publicity than his run-ins with the law. “Most of my work through the years has been related to the economic development of black people; I seldom do anything based on just making money for me,” he says.

Once, long ago, according to Ken Molloy, Brown asked him, “What can I ever do to repay you?” Molloy says he replied, “Help a kid like I helped you.” Years later, the two were playing tennis at the Port Washington Tennis Academy. Molloy was surprised to find that Brown knew the head pro, Bob Binns, a black man. “How do you know each other?” Molloy later asked Binns. “I grew up in Cleveland and Jim was of help to me,” Binns said simply.

Football hardly figures in Brown’s life today. His house, modestly furnished, lacks any memorabilia at all.” I don’t have trophies, I just don’t want ’em.” Sometimes he’ll turn on a football game, but rarely will he stick around for the finish. “I like performances, not games,” he declares.

But those performances never add up to his own. “I never think of myself as the best,” Brown says. “I think of myself as someone who performed the best in history. It’s not even close.”

And Walter Payton?

“Oh, that Walter,” says Brown with a smile. “You watch the heart of Payton. The heart is unbelievable. But Walter couldn’t jump in my face right now and throw me off the balcony.”

At age 50, Brown has already walked out on two careers. When he was 30, he simply failed to report to camp. “Although it was a good life,” he says, “I couldn’t take it too seriously. And I definitely did not want to get to a point where an owner didn’t want me anymore. That would take my self-esteem away.”

By then he was making The Dirty Dozen and in the midst of launching a film career. But that eventually ended, too. “I went out of style” is how he explains that one. “Now blacks only seem to be able to sing, dance, tell jokes and be in poverty.”

Jim Brown, once the man who so masterfully zigzagged across a field of play, leaving everyone in his wake, now seems a somewhat askew Don Quixote, forever flailing his sword at the windmills of injustice in his own life.

The football field that showcased his great talent was clearly outlined in white chalk, a measured 100 yards long. The windmills in the distance go on forever.

[Photo Credit: Malcolm W. Emmons via Wikimedia Commons]