In the candlelit quiet of Jim Brown’s living room, the unkillable Tee Rogers stands up and tells the hardboys that he is tired of all the death. Tee Rogers, the granddaddy of L.A. gangsters, whose resume reads, founder and chief rocker of the West Coast P. Stone Nation; shot four times, stabbed twice; beat up, sent up, but at no time shut up, tells the b-boys and Muslims gathered in this room that he can’t bear the tide of blood in the gutter. “God didn’t mean for black people to live this way,” he cries. “This is Los Angeles, land of liquid sunshine, of manifest milk and honey — God didn’t mean for me to be down on my knees that day, holding my dead homey in my arms.”

“Speak on it, brother,” came the collective reply susurrating around the room.

In his pretty African-print suit and matching hat, Tee Rogers bangs his fists together, bending into his rhetoric. “With all my cars, and all my diamonds, and all the power that I thought I possessed, I couldn’t bring that young boy back from the dead. l held him in my arms, his brains running like an egg all down the sidewalk, and all the king’s horses, and all the king’s men couldn’t put him back together again.”

An ex-Crip named Twilight stands up, much moved. He cradles his infant daughter to him; there is a terrible exhaustion in his voice. “I feel so hopeless sometimes. I’ve seen too much, and I can’t stop the memories. They come back on me strong in the night.”

A brief silence ensues, in which everyone is suddenly thrown back on his own stark memories. Meanwhile, sprawled on a couch at the head of the room, the top of his black sweatsuit unzipped, the greatest running back who ever lived weighs the density of the moment, and lets the silence play out for several seconds. When Jim Brown speaks, his voice is surpassingly gentle.

“What else is in your heart tonight, brother?”

Twilight, a young man with his own wounds to look to, clasps his child tightly. “I’m worried full-time about my baby, man. There’s too much bullets out there.”

If the South Bronx is America’s version of Beirut, then South Los Angeles is our Kuwait City. Something is always burning on the corner of Crenshaw and Imperial, and if it isn’t quite as spectacular as an oil-well fire, it’s no less inextinguishable. An entire generation has gone up in smoke, hundreds and thousands of kids hurling themselves onto the blaze of this thing they call gang-banging. No one knows for sure who started it or why, or who’s ahead in the body count. What people do know is that the 20-year firefight between Crips and Bloods has sucked all the oxygen out of the atmosphere, and installed the funeral service as a boy’s central rite of passage.

“What I see in South L.A. is a nation unto itself, a nation at civil war,” says Jim Brown, staring down in the direction of that disquieted place. He is leaning on the railing of his handsome terrace at the crest of the Hollywood Hills, from which vantage he can see the entire sprawl of the city as it slithers on its belly toward the valley. “And like all civil wars, this one ain’t nothing but wasteful, just tearing the hearts out of black people. Not,” he adds. “that any of my neighbors up here would care.”

From his heady perch atop Millionaire Mountain, it is not immediately clear why Brown himself should care. He certainly has enough problems of his own: a recent $70,000 judgment in back alimony against him; the loss of custody of his 8-year-old daughter, Kim, whom he hasn’t seen in a year; a career stuck in neutral since his demise as a film star 20 years ago; and an ongoing hassle with the L.A. county sheriff that has cost Brown a bundle in time and money, and more dearly still in reputation. His is not, you should understand, the standard profile of a philanthropist.

Indeed, the day this visitor dropped in on Brown. his 30-year-old Mercedes wouldn’t start. Elsewhere, one noticed encroaching signs of shabbiness: the broken basketball rim in the front driveway; the peeled plaster and jerry-rigged lighting in the upstairs bathroom. Here, evidently, was a life in need of its own repairs. How was it that Brown could afford to tend to other people’s woes?

Because, if for no other reason than pure self-interest, he can’t afford not to. After two decades of stumbling around in the dark, flitting from one failed venture to the next, Brown thinks he has finally hit upon both his calling and his main chance and has pushed all his chips in on it. His project, a “thing that’s been lurking on the other side of my mind for years,” he says, “always just out of reach,’” is called the Amer-I-Can Program, and what it purports to do is nothing short of miraculous: to teach gang kids and convicts everything they didn’t learn at home or at school — and all this in a 60- or 90-hour course.

“I’d go down to [South L.A.], or into the prisons, and see all these young brothers with heart and energy, and I’d ask myself, ‘What’s missing? What’s the one thing that’s holding each of them back?’ ” says Brown, explaining the program’s genesis. The answer, he lets out after a theatrical pause, “is life-management skills. I mean the most basic, fundamental things, like how to speak and think clearly. How to go out and present yourself for a job interview, or go about getting yourself some training. How to set up a savings account. How to handle problems with your girl. I’m talking top-to-bottom stuff that you and I take for granted. but without which these brothers ain’t going anywhere but down.”

“l tell them, ‘You ain’t in the joint because of what someone else did, brother,’ ” says Brown. “Don’t talk to me about the-white-man-this, my-mamma-that. It’s all on you, man, the whole nine yards.”

Marching into some of the toughest jails in California, Brown and his instructors, many of them ex-cons and former gang-bangers themselves, sit down with groups of 20 or 30 trainees, and painstakingly work through a slender green manual. Some of the chapter titles are “I Think, Therefore I Am;” “Conditioning Yourself For Success;” and “We All Fit In and Have a Place.” The program, as you can probably gather, goes whole hog on the homilies, and the first preachment is about responsibility.

“l tell them, ‘You ain’t in the joint because of what someone else did, brother,’ ” says Brown. “Don’t talk to me about the-white-man-this, my-mamma-that. It’s all on you, man, the whole nine yards. Now the question is, are you willing to take responsibility for your life and whatever becomes of it? Are you willing now to live up to your responsibilities to your family and to your community? If so, then and only then can we do business, gentlemen.”

“Responsibility” and “self-determination” are the buzzwords of Brown’s world view. He was preaching them in the ’60s, when blacks ignored him in their “stampede,” as he puts it, toward integration, and he’s still pushing them now, as the bell tolls for the Civil Rights Act. What the words signify is that blacks have been on a wild goose chase for 30 years; that, instead of civil rights, they ought to have been pursuing economic rights — the right to rebuild their own communities. the right to pursue their own fiscal destiny.

“Integration as a goal was the worst kind of joke,” Brown sneers. “All that time, all that energy that went into getting it. For what? So that I can go and live next to [L.A. police chief] Daryl Gates? When what we should have been saying is, No, we’ll stay right where we are, thank you, but we will take your liberal money, yes. We’ll use it to build our own schools and our own hospitals, and we’ll live in our own tidy neighborhoods, just like the Koreans and the Jews do. We might have wound up with a little less political power, but we would have had something way more important—buying power. And that’s the only power that means diddly in this country.”

Which is precisely what he’s trying to drill into his trainees. Sure, he says, there’s crack and there’s homelessness and a yawning abyss for black kids—but there’s also money to be made out there. Money for the kid who’s properly motivated (Chapter 2), has his priorities straight (Chapter 10), and can express himself clearly (Chapter 9). For that kind of kid, Brown insists, the sky’s the limit.

And whether or not he’s right, Brown at long last has an audience. Nothing has more enraged him than being ignored, and in the ’60s and ’70s, when he had so much to say, none of his people were paying heed. The field was crowded with both leaders and false prophets—Malcolm X, Martin Luther King, Huey Newton, Eldridge Cleaver—and Brown, who spoke softly and with considerable care, couldn’t be heard above the din. Bitter experience has taught him to turn up the volume, if only to be heard above the machine-gun fire, but what he has in growing numbers is a flock: rapt respectful kids who imbibe his every word. And what he’s preaching isn’t radical Marxism but meat-and-potatoes capitalism, the quarter-pound variety.

“Whenever anyone starts talking about Mother Africa, I just laugh in their face. I tell them, I’ve been to Africa, brother, and believe me, you don’t want to live there. It’s hot, and it’s backward, and there ain’t no McDonald’s there. No, this is still the greatest country on earth. Why? Because no one owns it. It’s perpetually up for grabs, and anyone can own as much of it as they’re willing to create, with their labor and their spirit and their imagination. And those things, my kids have in large supply.”

So far as their labor and spirit are concerned, some of them are about to get the chance to prove it. Next month, 20 graduates of the Amer-I-Can program, all former members of the Grape St. Crips, are off to San Diego to begin working on the construction of a new prison facility. The National Detention Corporation is an outfit building private, for-profit jails all over the country, and Brown has a contract to furnish it with labor. The 20 kids he’s sending down to San Diego will earn between $13 and $24 an hour, apprenticing as sheetrockers and window glaziers. By the summer, an additional 30 graduates are to be dispatched to other sites (in California alone, an estimated 65,000 jail cells are needed by the year 2000). with more to follow as the work demands.

Another track open for trainees is to become trainers, or “facilitators,” as Brown calls them. Amer-I-Can, three years old now, is firmly entrenched in most of California’s penitentiaries and Brown is negotiating with the states of New York and Ohio to bring the program in.

And there is a need for it in other kinds of places, as Brown is finding out. Gene Jackson, the operations manager of Nicholson Gardens, the largest and most notorious housing project in Los Angeles, recently contracted for the program as a preventive measure. “The gang activity in Nicholson is unbelievable,” reports Jackson. “One drive-by shooting last Sunday, another one on Tuesday. Kid in a phone booth just blown to shreds. But on the kids in the program, there’s been a powerful effect; its antigang message really gets through to them somehow.”

There is also talk now of teaching it in inner-city high schools in L.A., particularly to juniors and seniors. Wherever the program goes, people will be needed to coordinate and teach it, which means jobs for Brown’s graduates.

“See, that’s the thing that black leaders in this country have never understood. These kids aren’t interested in equality or integration, or any of that other crap we fought for in the ’60s. They’re interested in jobs, man, that’s the great emancipator. To them, everything else don’t add up to [expletive].”

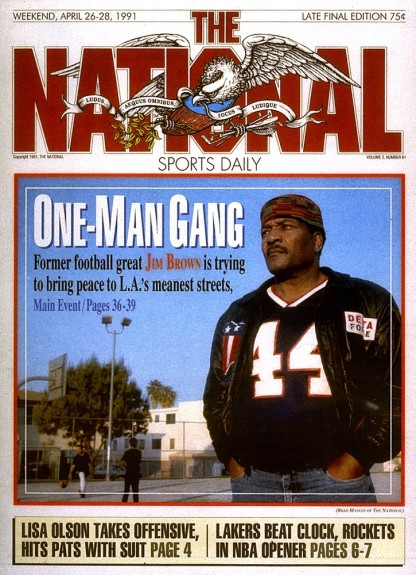

Whatever their first impressions are of Brown, it’s a sure bet none of his trainees are nodding off on him. At 55, the man is as big and hard as the bald mountains off Highway 1. The body, all 6 foot 2 and 235 pounds of it, looks precisely as it did 30 years ago: swooping, explosive, immense through the back and shoulders. The face, however, once insuperably handsome, has taken on the marks of his personality. Stony, and deeply furrowed beneath the eyes and nose. there isn’t a glimmer of anything like laughter in it. Almost always expressionless, it is nonetheless terribly expressive: of fatigue, and impatience, and most of all, rage — rage on a high boil, with the lid clamped tight. It is a face to which you immediately defer, or risk the consequences.

Only one kid. to Brown’s recollection, has chanced it so far. “A young gang-banger, one of Tee’s friends, came up to my house for a meeting one night. He had a couple of beers in him, and maybe something else besides, and was getting a little wild with me, so I gave the brother a chance to exercise his aggressions. We went out into the hallway, and I said, ’OK. I’m the ball-carrier, you’re the defender: Tackle me.’ Well, he comes on, drives his shoulder into me pretty hard. But with my free arm, I picked him up by the waist, slammed him onto his back, and sat down smack on top of him. As I remember, he seemed to calm down a lot after that.”

If that isn’t exactly the model of modern pedagogy, well, these aren’t exactly model students. “The kids I work with aren’t just tough, they’re warriors — they literally fear nothing. That’s why l understand them so well, I’m a warrior, too. Being a warrior means resisting till your last ounce of strength, but it also means respecting a fellow warrior. For me, that meant respecting people like Sam Huff on the field, and people like Malcolm [X] and Paul Robeson off of it. For these kids, it means respecting me not because I’m Jim Brown, but because I’m big enough to defend myself against anything they got.”

Anything, that is, except their hardware. Brown holds two kinds of meetings at his house. There is the organizational sit-down with key people in the program. Then, far less frequently, there is a kind of summit between sects of Crips and Bloods, in which Brown tries to use his influence as a venerated warrior to stop the killing when it’s out of hand. At these parleys, his security people (dark-suited members of Rev. Louis Farrakhan’s Fruit of Islam) have all they can do just to confiscate the guns at the door. Uzis, 9mm semi-autos, and the crowd-killing Mac-10s line the walls of Brown’s long foyer.

“Man, it gets tense enough in here, believe me, without the guns,” says Brown “The stare-downs, the back-and-forth between these boys. They’re so wired to blow that one little insult—hell, one perceived insult—could set something off that it’d take the National Guard to put out.”

To spend any time at all with Jim Brown is to realize he is a man without a city. In South L.A., he is conspicuously misplaced, a superstar among gangsters. In North L.A. he is equally misplaced, a gangster among superstars.

Which raises a fundamental question. How do you take kids so steeped in the culture of violence and sell them on the virtues of a job hanging sheetrock? Put another way, if a kid’s been “bangin’ and slangin” (doing crimes, selling crack) for serious money, where’s the glory in making $14 an hour?

“First of all, we need to make a radical alteration in your perception of gang-bangers,” says Tee Rogers, who, plump and droll, looks like Sugar Bear in the old Sugar Smacks commercials, and who, woken out of a dead sleep at four in the morning, could win a one-on-one debate with Jesse Jackson cold. “Only prime-time players like me made Mercedes money. The rest of them are down there scratching for that five-and-dime nut. They’re thrilled with $14 an hour, it’s got that $3.35 at Burger King all beat to death. Plus, they don’t have to kill anybody for it.”

Fair enough. But even in this bloody age, how long before the boomlet in jail building gives out, and a lot of these kids find themselves right back where they started—unemployed, uneducated, and trailing a rap sheet besides?

“I’ll tell you what I tell my trainees,” says Brown. “This ain’t the Job Corps, friend, I’m not here to babysit anyone. The goal of this program is self-determination. The six weeks of training, that first job glazing windows—those are just steps, man, stages along the path to success. We put our people on that road, and we support them down the line with our love and our friendship. But the rest is up to them.

To spend any time at all with Jim Brown is to realize he is a man without a city. In South L.A., he is conspicuously misplaced, a superstar among gangsters. In North L.A.—the L.A. of Spago, and Madonna, and $7 million houses—he is equally misplaced, a gangster among superstars. He has citizenship in both places, and is fluent in both dialects. But at night, when you really find out who your neighbors are, Jim Brown is alone in his yellowing kitchen.

For a while, he had it both ways. He made some bad movies, threw some great parties, and was as apt to compete with Frank Sinatra as Fred (The Hammer) Williamson for an 18-year-old blonde who looked 20. But at some point, the scripts stopped coming, trouble with the sheriff started, and Brown suddenly found himself a conspicuous outsider in the ultimate insider’s town. Rather than leave, he holed up, and is holed up still, a huge, stubborn bird in his gilded cage.

So odious is the history of his arrests to him that it is the one thing Brown will not talk about. Raise it, and his eyes irradiate, charging the atoms between you and him. But, dismissing the matter with a sneer, he cannot dismiss the harm it has done him. And whether or not he has been persecuted for “being black and outspoken,” as he alleges in his book, Out of Bounds, some of that harm has unquestionably been of his own making.

“The one time [Magic Johnson] ever showed any heart, the people turned on him fast, and he couldn’t deal with that. He needs the adoration too much. He’d rather be loved than be honest.”

One of Brown’s self-admitted “weaknesses” is his propensity for slapping women. Another is his habit of getting into screaming matches with them, alarming neighbors who summon the cops. Whatever else Brown was doing the night he was arrested for throwing a woman named Eva Bohn- Chin off his balcony, he was certainly slapping her and screaming at her. He beat that rap and several others, but he didn’t skate on charges that he punched a golf buddy over a ball placement. That bit of pique cost him a day in jail and $500, and chipped away at what little luster his legend retained. And if North and South L.A. have anything in common, it is that in both places, one’s legend is merely everything.

Having made the least of his legend, Brown chafes at the mention of people like Magic Johnson and Michael Jordan, black superstars who have made the most of theirs. Their salaries befuddle him, their political silence infuriates him, but what really seems to burn him is their popularity. Like Brown, they have been indescribably brilliant; unlike Brown, they have also been beloved. And so, Brown, who wants so much to be seen and heard, is ignored by all but a handful of street kids, while Magic and Jordan, who have nothing particularly to say, are consulted like magi.

“I’m as capable of doing weak and shameful things as anyone else, but one thing I cannot do is lie,” sneers Brown. “If I could, I’d be living right next door to Magic, who hasn’t told the truth since he popped off about [former L.A. Lakers coach Paul] Westhead eight years ago. The one time he ever showed any heart, the people turned on him fast, and he couldn’t deal with that. He needs the adoration too much. He’d rather be loved than be honest.

“Same thing with Michael. Strictly out for his, and to hell with his people. No consciousness of who he is, or what his history is. Both he and Magic are modern-day versions of the old mulatto slaves who, because they had three or four little drops of white blood in their system, got preferential treatment. Nothing new there. Isn’t it a characteristic of the house nigger to want to be just like his master?”

The conversation goes on, and more and more blacks wander into the line of fire. “Michael Jackson! What the hell has he ever done for black people? There ain’t a worse white man alive than Michael goddamn Jackson.” Spike Lee: “I mean, I just don’t get it about him. Has he made anything worth watching? Has he said anything worth repeating? Not so’s I’ve noticed.” Walter Payton: “Compared to me, Walter isn’t Sweetness, he’s Sadness. He never dominated the game, never even won a rushing title. He just hung around long enough to pick up a bunch of yards.”

Clearly, politics is no longer the issue; fame is. While new icons bubble up every 15 minutes, Jim Brown looks on from his patio, glowering. He has, he says, all but been written out of history by “people who tried to deny what I had done, who played with the statistics to prove that someone else was better.”

The phone still rings, but none of the callers inquires about him. Instead, they want to know his take on Bo Jackson, or what he thinks Barry Sanders would run for on a grass field. And patiently, Jim Brown delivers up quotes, partly because it pleases him still to be asked, but also because if he didn’t, the phone might stop ringing. And in 55 years of hard yards and hard cuts, that might be the hardest cut of all. Because although there is finally work that consumes him (he estimates he puts in 60 hours a week on the Amer-I-can program), an old yearning throbs inside him. He is right when he says that, as a rule, you have to choose between being honest and being loved; you cannot have it both ways in America.

But, having been the exception to so many rules by sheer dint of greatness, it hurts Brown not to have been an exception to this one, too. No one, however angry, wants to be unloved, and in his warrior heart, Brown bleeds for not having been cherished. Isolation is a grievous price to pay.

There is a videotape he has of a speech Bob Knight made, introducing Brown to an Indiana audience. Knight, clearly winging it, rattles on a while about Brown’s brilliance as a ballplayer. And then, out of the blue, he says something quite stirring, and unwittingly prescient about Brown. He says Jim Brown was one of the five most courageous men he’d ever met, because “in nine brutal years in the NFL, he never once ran out of bounds. No matter the pain, no matter the game, he never once ducked a hit.” Brown, watching the tape, is unabashedly moved, and it is not hard to see why. At last, someone understands what it is like to be Jim Brown, straining for every yard against phenomenal resistance, no little of it his own.

[Photo Credit: Lizzie Chen/LBJ Library/Wikimedia Commons]