New York

Given the nature of movie imagery, which is strong, persistent, and sometimes indelible, we may be pardoned if we think of Lauren Bacall as a woman who combines steely independence with a sassy, unflinching social ease. Except, of course, she won’t pardon us because, dammit, we really should know better than to confuse the real person with the performing persona.

The one up there is Lauren Bacall, a Hollywood invention whose presence, a critic once observed, lends new meaning to the term Bitch Goddess. The one down here thinks of herself as Betty Bacall, gets the shakes making an entrance alone in a room full of people, turns to jelly at the sight of such sentimental monuments as the Arch of Triumph, longs for a man to lean on, and assesses her temperament as vulnerable and romantic. Also, she’s scared.

All but the last detail has been gleaned from her forthcoming book, which, naturally enough is the source of her apprehension. Mind you, it is not the critics who worry her. Convinced that film and stage critics don’t know beans about the art of acting, Bacall is nearly as certain that book reviewers are equally at sea about the craft of writing.

In any event, she plans to avoid the reviews, having found that praise and blame are usually bestowed for equally invalid reasons. But what is she going to do about this feeling that she is, metaphorically speaking, naked to the world? Her long, bony fingers carving arabesques in the air, little gold rings glinting in the lights of lamps lit against the violent dusk, she tries to explain:

“When I turned the book in, I really did have postpartum depression. I really felt I had given up my child. Certainly, I’d given up my life. Now suddenly a lot of people are going to know much more about me than I ever thought they would. And I’m not going to know which ones know.

“And there are people who are not going to like what I say and people who don’t think I can write and people who still aren’t convinced that I did it myself and people who are not going to approve of things that I’ve written about various people. I know that’s going to happen.” There is scarcely a beat between this fit of uncertainty and a classic Bacallian method of dealing with opinions she does not value. “Well, what the hell. I can’t do anything about that.”

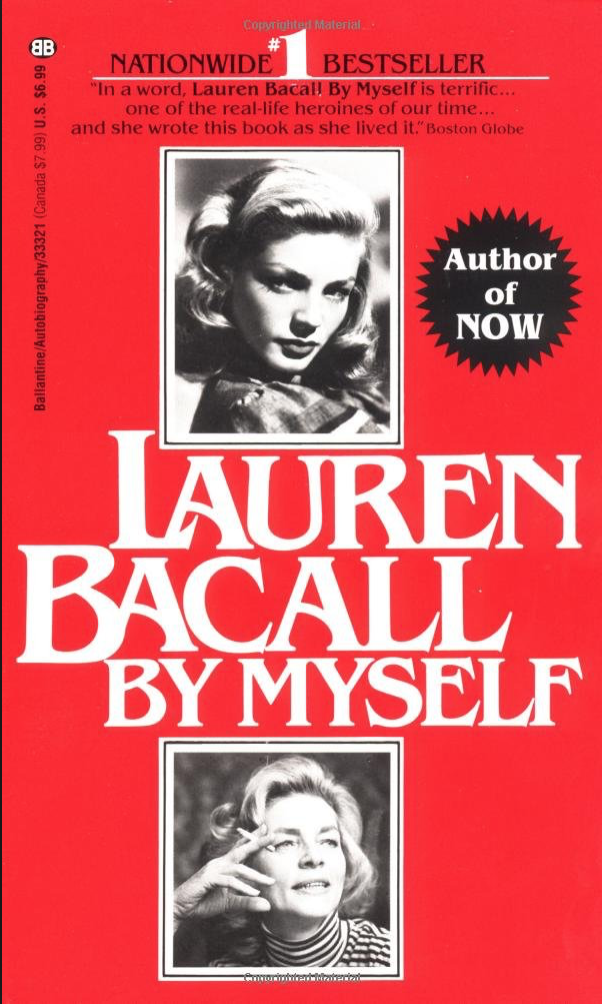

The book is called Lauren Bacall By Myself, and even a casual prowl of its pages can leave no doubt that Bacall had hardly any help. She wrote it between acting engagements over a three-year period, by hand on yellow legal pads, mostly in a series of temporarily empty offices at Alfred A. Knopf that proved to be the only distraction-free place she could find. It is all Bacall, including the sentences that don’t parse, the feverish dashes that replace conventional punctuation, and the tendency to describe emotion in terms that echo the movie clichés of yesteryear: “When we looked at each other, trumpets sounded, rockets went off.”

“How can anyone be happy in this world? You have to be an idiot to be happy.”

She tells us about Betty Jane Perske, a nice, sheltered Jewish girl from New York who cried at movies, who worshiped Bette Davis, and who, at twenty, was transformed into a movie siren in her very first film, To Have and Have Not. She tells us about the near-idyllic marriage to Humphrey Bogart, cruelly ended by cancer. She tells us about the near-marriage to Frank Sinatra, aborted by Sinatra’s mercurial disposition and his apparent incapacity to deal with any human relationship as a grownup. (“Don’t tell me,” he would demand. “Suggest.”) She tells us of the eight-year union with Jason Robards, done in by drink and his need to wander. She tells us she was spoiled, selfish and self-absorbed. She tells us nothing more piercing than a single line memorializing her young Hollywood days and her twelve years with Bogart: “Whenever I hear the word happy now, I think of then.”

When the sentence is read back to Bacall, she looks suspicious and faintly menacing. She is under the impression that she has been especially revealing and is wary about questions that seem designed to carry any point out of the shallows where much of her book dwells. Finally, she says: “I have not been happy in the full sense of happy. Number one, I think that anyone who has any brain at all—how can anyone be happy in this world? You have to be an idiot to be happy.

“But I think certainly then I had the world by the tail. I was nineteen years old. I was in love with a wonderful man who was in love with me. I had made a big hit in a film. I had everything anyone could possibly dream of, more than I ever dreamed I would have at once.

“I certainly have not had anything comparable to that feeling since. I’ve had rewarding moments. I love my kids. I have terrific friends. I have a lot of pluses in my life. But to say that I myself have been happy? I’ve had moments of feeling happy, but that’s all. I’ve had nothing for long.”

Publishers have been trying for years to put Bacall in print. “I’ve been asked to write books about myself and Bogie, which I always said I would never do, and books with pictures and coffee-table books and blah-blah-blah.” Knopf’s editor-in-chief, Robert Gottlieb, succeeded where others had failed for a number of reasons. Chief among them, says Bacall, is that “he did not want anything cheap. He did not want anything sensational. And he wanted it to be about me. Bogie was part of my life, but he was not all of my life. Most people wanted only that. I said I would not do it. I’m not out to make a buck on my marriage and my first husband and on his fame and on his legend. That was twelve years of my life. I’ve lived a few more than twelve years.”

Bacall will make a bounteous buck indeed out of her life story, but it’s no use asking her for details. At Knopf, which ordered up a handsome first printing of 100,000 copies, it is already seen as “a million-dollar book” based on sales of reprint rights. The English, the Swedes, the French and the Italians have bought it; Family Circle here and The Daily Telegraph in London each paid better than $100,000 for excerpts. a nice piece of change for a woman who is no stranger to thrift. An inquiry about profits brings from her a frosty reply: “It’s been sold in many places. I don’t intend to discuss figures. I haven’t gotten rich from the book yet. I hope I will, but I haven’t.”

Her blue eyes have turned cool, glacially neutral. She fingers one of several gold chains on her brown sweater and glances at the dog sprawled across her skirt in blissful sleep. He is Blenheim, a Cavalier King Charles spaniel, and they love one another. Outside the tall, uncurtained windows lies Central Park, a stretch of sere and wintry brown, and beyond that the silhouetted skyline of New York’s Upper East Side. For eighteen years, Bacall has owned an apartment in the Dakota, a prestigious, venerable West Side building with soaring ceilings, three-inch-thick mahogany doors, and immense rooms, each with a brilliantly embellished fireplace.

We are in the library, perfumed by the narcissus growing in a bowl on the coffee table and artfully cluttered. The place is a tribute to decades of exploring the world’s antique shops. Bacall doesn’t collect things, she collects collections: little brass boxes, oil paintings of cats and dogs, Ashanti gold weights, pearl-inlaid furniture. Lately seized with a passion for early American quilts, she has acquired enough to cover all the beds in four bedrooms, to change them seasonally, and to decorate the rooms of the weekend place she acquired a year ago in Amagansett, on the eastern end of Long Island. She buys them compulsively and in quantity and won’t even guess how many she owns. Genuinely appalled, she begins to enumerate the objects she can’t resist: “Faience, pewter, good old furniture—you name it, I buy it. It’s awful.”

When she is not worried that an effort is underway to extract information that she’s not prepared to surrender, Bacall is a quite cozy, likable woman with a modest gift for self-mockery and a tendency to offer up details no one has thought of soliciting.

“I can see where my face could be improved. But I also feel your life is in your face. Now, I’m going to sound awfully silly if two years from now I go and have a facelift. I’m fighting it. I may lose, but I’m fighting it.”

Cracking and consuming walnuts out of a silver bowl, she glumly reveals that she is struggling with eight unwanted pounds. Not readily apparent under the folds of her gathered brown skirt, the extra weight arrived after a successful course with Smokenders during which she cured her addiction to nicotine and took up candy bars. For the first time in her life as a naturally slender person, she is having trouble slimming down.

Then there is the matter of the natural erosions of time and the way in which Americans culturally deal with them. Bacall has strong opinions on the subject, and they come roaring out:

“This country drives me up the wall with that attitude about age. That everyone has got to have a facelift is so depressing. One must not have a line. To see those pictures of Betty Ford side by side, you just want to cut your throat. I mean—what is it? We’re all convinced we must look young. Madness. Sad.

“I can see where my face could be improved. But I also feel your life is in your face. Now, I’m going to sound awfully silly if two years from now I go and have a facelift. I’m fighting it. I may lose, but I’m fighting it. People tell me, ‘Why not It’s part of your business. You should have a little thing done here and a little thing there.’ Half the people I meet think I’ve had one anyway. After thirty-two, if you look good, you have got to have had cosmetic surgery.”

Lauren Bacall is fifty-four and she looks good. There’s little point in asking her about the rewards of maturity—she has no talent for introspection. If anything, the years have given her more things to be indignant about. She is angry about a movie business that in general has no interest in stories that might reflect the lives of women who are no longer young. She doesn’t think much of the new Hollywood, deploring the disappearance of the old studio system—“the good times,” which she devoutly believed fostered an unmatchable range of talented stars and creative people. As for many of the new performers now rated as stars, “Ten years from now they will never be heard of again. Everyone is a star for two minutes.”

Since Bacall’s great long-running hit in the 1970 Broadway musical Applause, she has worked less than she would have liked. She has a role as a fanatic nutrition expert in the new Robert Altman film Health, to be shot in Florida this winter, and the prospect genuinely excites her. But opportunities of that sort are rare. She turns down scripts regularly. “I’ve been sent an average of two or three plays a year lately—one worse than the other. They’re awful. It’s all well and good to do things for money if occasionally you have to, but not a film that’s going to come back to haunt you and certainly not a play that you have to do eight times a week. I couldn’t bear it.”

Work is important to her, perhaps, she muses, the most important thing in her life. She is not ruling out other essentials. Bacall is a woman who likes and needs male companionship, but the possibilities for permanence seem dim. During a two-year stay in England, for the London run of Applause and then the filming of Murder on the Orient Express, she fell in love with a married Englishman. They had a “happy” six-month relationship that came to a “devastating” end. And that’s all anybody needs to know about that affair.

Now she leans back in her chair and calmly confronts a future alone. “I think it is very possible that I will spend the rest of my life by myself, just because the averages are not necessarily in my favor. I had it terrific once and that’s it. How many chances do you get?

“I’m not desperate about it at all. I just feel that I don’t want to waste my time and that I really want to spend my life doing what I want to do. I don’t want to give myself away. I don’t want to go to cocktail parties any more. I could spend all of my time going out, because the whole world would have you decorating their living rooms.”

Actually, as a resident and available star, Bacall is on everybody’s party list, and her face or name seems to turn up in the columns for at least one big New York event a week. But she insists she avoids most of the big bashes. “I don’t want to dissipate my energies. I would like to focus on my friends, my work, my children.”

There are three children—two Bogarts and one Robards. Bacall is pleased with them. “I think they have all turned into very good people. I don’t take credit for that. I think you can give your kids everything, and they can turn out badly. I think they must finally take some of the responsibility.”

Steven Bogart, married and the father of a son, went back to school after six years as a dropout—“a late bloomer like his father”; he is graduating from the University of Hartford in May, and will work in some aspect of television news. Her daughter, Leslie, is a nurse. Her youngest. Sam, is seventeen and in his last year in high school, and with any luck will be the third generation of Robardses in the acting profession.

“He’s been around Jason a lot in rehearsal, he’s been on tour with Jason and with me, so he knows an actor’s life is hard work. I would never point any kid of mine in that direction because I just think it’s too tough a life. But, by God, in Sam’s case, I just know he’ll make it.”

She took Sam off for a Christmas visit in London, a little breather for her before a bone-crushing, fifteen-city tour on behalf of By Myself. London has special appeal for her, and she looks back on her two-year stay with something like longing. “It is quieter, it is cleaner; it has more to do with yesterday than with today. There’s no question that it’s easier there. And that’s why I left.” There were, after all, today and tomorrow to be faced. Besides, she knows very well it’s not supposed to be easy.