I remember Lee as he himself—were he able to remember anything now, God rest his soul—would have wanted to be remembered. Of this I am certain. Why, it was just two years ago when we huddled together in our booth at the Russian Tea Room, laughing and gossiping and slurping borscht, for what seemed like three and a half hours. Not that anyone was counting. When you were around Lee, time stood still. He was that way. “This is faaabulous,” said Lee that day, as he probably said every day, in that very warm and special whine of his. But that’s the kind of man he was. By man, of course, I mean giant, although I am sure he could wear a 40 Regular with negligible alterations. But I digress…

Lee, we hardly ye. Though you’re gone, I’ll be seeing you in all the old familiar places that this heart of mine embraces all day through. Mostly, however, I’ll be seeing you in the first scarlet banquette beyond the bar, nested beneath—and looking very much like—the brass samovar and the tinsel garland and the flowers. And I say this with all due respect, because I know that it is exactly the way you would take it. That day was pure Lee, and by Lee, of course, I mean Mr. Showmanship, the grandfather of glitter, the sultan of schmaltz, Wisconsin’s favorite son, Wladziu Valentino Liberace. In that moment, the Russian Tea Room was abuzz, his name on everyone’s lips. But then New York was his Easter egg that month, as he prepared for his second record-breaking Radio City concert series.

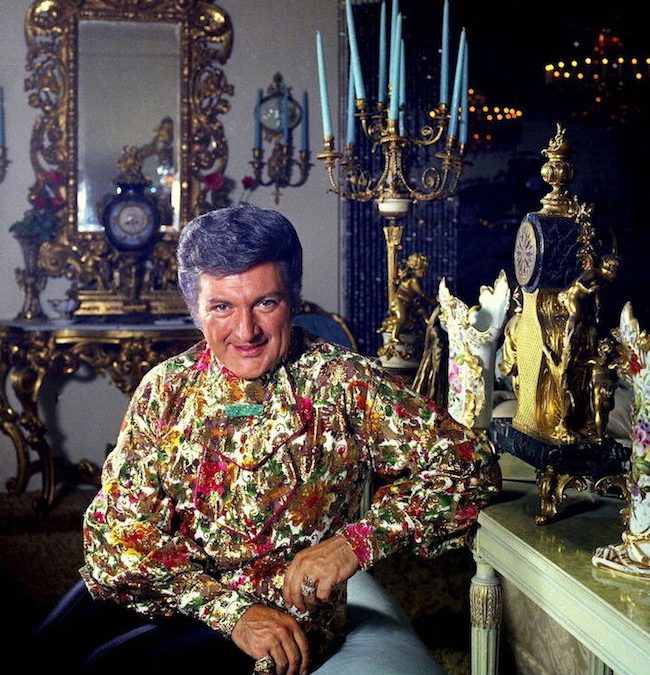

The Lee I knew looked as natty as a boulevardier, in a vanilla double-breasted sport coat with turquoise slacks, tie, and handkerchief. He had brought with him–because a man of this stature cannot just go out alone, you understand—a publicity yenta who kept talking about “killa Bloody Marys” and a sturdy, bronzed and bejeweled young man with highlighted hair named Cary-James. Onstage, Cary occasionally played Lee’s “chauffeur,” the one who peeled off Lee’s fabulous furs and, feigning a hernia, lugged them into the wings.

I remember once asking Lee—it was that very day, in fact—to name his favorite fur. Lee winked at me, as he was wont to do, and mewed, “The newest one! Always the newest one!” Oh, how we laughed. We also spoke of his rings and how he had to glue them to his fingers before performances. He did this to prevent fans from pulling the rings off when they shook his hand. “You’d be surprised how often they try,” Lee told me, adding, “Even if they grabbed one and ran like hell, they’d never get out the door.” Cary said, “But people think they can really get away with it, to have a piece of you.” It was the publicity hen who then, I think, put it best: “One thing about, you, Lee, is that fans are not content to just see you across the room—they want to touch you.” We all quietly contemplated that for a moment.

What an appetite for life that man had. But for now, let’s limit it to food. “I’m eatin’ bread like it’s goin’ out of style,” he mused that afternoon. I will always remember the way he ate bread, and this is something I’ve never told anyone. So meticulous was he that after buttering his pumpernickel, he would take the greasy knife and use it to pick up every crumb from the tablecloth. He would then slather the crumbs back onto his bread and gobble it down, repeating the process throughout the meal. I remember thinking, Here is a man who savors—who luxuriates, if you will.

I can still hear him ordering his lunch: “Would hot borscht be considered an appetizer?” he asked one of the waiters, who nodded and suggested sour cream on the side. “I like it in the middle,” Lee proclaimed. “Then, for an entrée, what am I gonna have? Oh! I love chicken Kiev. The butter oozes out?” he inquired. The waiter assured him that it was so. “All right, I’ll have that! And how ’bout a little ratatouille too? Gee I sound like a horn.” Such was his playfulness with language.

The child in Lee, as you can see, was irrepressible. When I mentioned his turn as guest villain on the old Batman TV series, he grew euphoric. “Oh God, I loved that,” he said.

And wasn’t that exactly like Lee? I think it was. A restaurateur in his own right (his pasta palace, Tivoli Gardens, adjacent to his personal museum, is Las Vegas personified, if not more so), Lee was a man who knew his way around a griddle. “I’m an experimenter,” he said to me in a sweet revelatory moment. “I take a basic recipe and I add to it.” That could have been his philosophy of show business, but alas, we were still talking culinary commerce. Recipes for Liberace Lasagne and Liberace Sticky Buns were included in his book The Wonderful Private World of Liberace, and I don’t mind telling you that both are delish, as Lee so often put it. As he himself wrote: “You should serve my sticky buns while they are still warm… Believe me, there’ll be none left over.” How right he was.

It is no wonder that people were drawn to him, as if he were a shaman. And never were they rebuffed, even when they may have deserved it. There was the furtive approach of Joe Raposo, one of the legends of the business, who wrote songs for Sesame Street. “Oh yes, all that good stuff,” said Lee, perhaps a little too patronizingly, or so I thought. “Mr. Liberace, you’re the sweetest man in the world,” Raposo said. “We have many friends in common, and they always speak of you with such love.” “Aw,” said Lee, which was typical of him, “that’s nice.”

Later, the incomparable Miss Eartha Kitt, in an orange turban, slithered over from another booth, and much hugging ensued. “This gentleman and I used to walk up and down Fifth Avenue at five o’clock in the morning,” she purred, incomparably. “He pointed out the jewelry in the windows of Tiffany’s and Cartier’s and never bought me a thing!”

“Never!” echoed Lee. “But we were great lookers, weren’t we? So how’ve you been? Whatcha doin’, whatcha doin’? Tell me.”

“Getting ready to go to Europe,” she replied. “Where are all your jewels today?”

“I put ’em in the vault.”

“I’m still waiting for you to buy me one of those things,” Miss Kitt persisted, pointing to the lone opal ring he wore that day.

“I know,” said Lee, sighing. “Cheapo, cheapo.”

It should be noted that Lee’s New York was really not all that different from your New York or my New York. He may have been holed up that month in a Trump Tower apartment, but Donald Trump was paying. No, Lee’s pleasures were the simpler things—and isn’t that so telling? “There are so many sights in New York that you could only see here,” he would say, profoundly. He rhapsodized over visiting the kitchen of Balducci’s. “Everything I admired, I wound up with a carton of,” he marveled. Of some hookers he’d seen soliciting outdoors, he crowed delightedly: “They wear nothing!” And so enamored was he of the Pathmark supermarket near Chinatown that he boasted of filling three shopping carts whenever he stopped in.

“You know, I found the cutest thing at Pathmark,” he practically squealed at one point. “It’s a rabbit holding a carrot, and when you squeeze the carrot, it plays ‘Easter Parade.’ Soooo cute. They’re only eight ninety-nine, but they look like FAO Schwarz. I mean, they’re faaabulous. I want to buy one for everybody, but they’re completely out of stock. I told ’em to reorder.” (I would later learn that he called such bestowals “happy-happys.”)

The child in Lee, as you can see, was irrepressible. When I mentioned his turn as guest villain on the old Batman TV series, he grew euphoric. “Oh God, I loved that,” he said. “I played a dual role, you know. Two brothers: one was the pianist Chandell, whom I did as an exaggerated Liberace, if that’s possible. Very exaggerated. The twin was a gangster, so I played him as Edward G. Robinson. I’d be puffin’ on cigars and using a gravelly voice.” He growled a little here.

“You know, it’s in my contract that I’m not allowed to go to the bathroom. I’m gonna get some of those Depends, so that when I have to go to the bathroom, I can sit still and let my shorts turn to jelly.”

I would be remiss not to recall Lee’s views on professional wrestling. By coincidence, that very week he was to climb into the ring at Madison Square Garden to dance with the Rockettes in Wrestlemania. The prospect made him giddy. Lee told me, “Forget Carnegie Hall, forget Radio City, forget the Royal Command Performance—if my mother were alive today, she would say, ‘Son, you finally made it!’ She was such a wrestling fan, I can’t tell you. This sweet lady who was so proper and so elegant and never said a nasty word in public would sit there in front of the TV and scream, ‘Kill the bastard, the dirty son of a bitch!’ I’d say, ‘Mom! I’ve never heard those words come out of your mouth!’ She’d grit her teeth and scratch at the upholstery and swear some more. I’d say, ‘C’mon, Mom, it’s all fake!’ She’d holler, ‘Don’t you say that! Look at that blood—it’s real!’ Oh, if she could be here today.”

None of this is meant to suggest that Lee and I didn’t share serious times in the hours we knew each other. I remember how unsettled he looked when I asked whether he had ever been burned by wax drippings from his candelabra. “I was forced to go electric” was all he said, and I respected him for it. On the subject of overexposure, he became self-conscious and slightly abrupt. “In the late fifties, I was on TV ten times a week,” he said gravely. “I got the hell out of the country and went to London and my career was like brand-new again. There is such a thing as staying too long at the fair, you know?”

For some reason—and I will forever be grateful for this—I got around to asking him about the afterlife. “Actually, I’m sort of in reverse,” he confided: “I feel like I’ve lived before. Sometimes when I put on a period costume I seem to know just how to manipulate it, how to put it on. I favor those past eras, which some of my homes reflect. Like the Napoleonic time and the Victorian time. I love imagining I lived in those days.” He added, portentously, “The future is something that is less understandable.”

What happened minutes later will remain perhaps my most haunting memory of Lee. Another aide arrived, bearing dozens of cards for him to sign that would be sent with flowers to friends. Lee wearily drew a long breath and began to write LlBERACE LOVE on every card. “I do have a life of my own,” he softly grumped. “Nobody seems to know it but me. You know, it’s in my contract that I’m not allowed to go to the bathroom. I’m gonna get some of those Depends, so that when I have to go to the bathroom, I can sit still and let my shorts turn to jelly.”

Then he laughed fabulously, and wondered aloud, “Say, who’s payin’ for all these flowers, anyway?” But that was Lee all over.

[Photo Credit: Allan Warren c/o Wikimedia Commons]