At this time of year, at this time of morning, it was still dark. A small crescent moon hung in the Indiana sky and, beneath it, four helicopters balanced, as if some fantastic throbbing mobile had been constructed for the occasion. The citizens stood in a field of corn stubble across the road, and, closer to the prison itself, reporters and photographers crunched back and forth across gravel. A garden of satellite dishes bloomed in the parking lot. And inside the yellow police tape, much closer to the prison, mysterious-looking men in black fedoras and big overcoats clustered, their garb and secrecy setting them apart from any other crowd. Black limousines slid back and forth across the entrance.

Mike Tyson was still in the Indiana Youth Center, a medium-security prison outside Indianapolis. He’d been there for three years, doing famous time for raping Desiree Washington, an eighteen-year-old contestant in the 1991 Miss Black America pageant. Many predictions of his self-destruction had been fulfilled with that act—George Foreman had long ago warned, “He needs to be sheltered like you would shelter a lion or a tiger. You lock him up, except when you want him to come out and jump through a few hoops”—and for three years a nation had been smug in its revulsion.

But now, the only athlete ever to have been imprisoned in the heat of his career was about to step from behind those walls to reclaim lost time, and that same nation—the world, even—had come to see how he’d do it. Fascination replaced disgust, many times over.

Three years in prison, while he stewed in bitterness, might even have made him dangerous in ways beyond his previous flamboyance.

Even before his crime, he’d been a strange melding of melodrama and malevolence, more a presence than an athlete. His appetite for subjugation, which had been illegally satisfied behind closed hotel doors, was also the basis of his $70 million career. In his last full year of boxing, people paid $16 million to watch him consume the weak. What he’d done to Desiree Washington was horrible, of course, but it could also be seen as a failure to discriminate, a momentary inability to distinguish between teenage girls and heavyweight contenders. On his release, whether or not he’d been forgiven, he had perhaps become more interesting than ever.

Three years in prison, while he stewed in bitterness, might even have made him dangerous in ways beyond his previous flamboyance. Three years ripped right out of him, when it is time that is always the principal factor of wealth and achievement in an athlete’s young life. That lost time denied him earning power, and maybe his place in boxing history. He had been stubbornly unrepentant in prison, so it didn’t seem likely he’d forgive the debt. All the powers of the media were trained upon him this cold morning: What was he like? What would he do? How did he plan to make us pay?

One open question was, what was he worth? It was a tough calculation. He was already 28 years old on the day he was freed, and nobody knew if he could still fight. By most reviews, he had already been fading by the time he went to jail. His aura of invincibility, so impressive and effortless in his youth, had become a clunking and largely artificial apparatus. He’d been beaten by James “Buster” Douglas in Tokyo in 1990, and had fought two difficult fights with the otherwise unimpressive Razor Ruddock in 1991, leaving all those one-round knockouts of his early career, all those titles, to be reconsidered. Still, even behind bars, he was the most exciting heavyweight in the world. And all this attention at his release demonstrated some kind of demand for his services, or maybe just for his personality.

If he remained a little enigmatic, or at least contradictory, in this exile, there wasn’t that much concern about his future, not really.

There were, naturally, some people under that Indiana moon who wondered if he had any value as an athlete at all, whether time had changed or diminished him to the point where he no longer had a promotional utility. The sporadic reports that had come out of the prison in the three years past had Tyson reading cartons of Communist literature and taking instruction in the Muslim religion, which was probably not good news for the game. One interview he did put him at such odds with his former boxing persona that you might well have guessed he was planning to enter a far less secular line of work. He said he had been “wrong and disrespectful” to dehumanize his opponents, and he was sorry he had ever said he would make Tyrell Biggs cry like a girl or that he would make Razor Ruddock his girlfriend. “I will appreciate their forgiveness,” he said. Also, he wanted “to see the great libraries” once he got out.

It was an interesting idea, that Tyson had devoted himself to some kind of intellectual and moral development, though it was clear he would only do so on his own terms. He surprised Maya Angelou on a visit when he recited her poetry back at her. Yet he could not pass the GED exam that might have shortened his sentence. He told interviewers he was reading Malcolm X, but he got into a jail-yard beef with a corrections officer. He had another con put broad likenesses of Arthur Ashe and Mao Zedong on his arms, but he refused to apologize for the rape, an act of contrition that also would have sprung him early.

If he remained a little enigmatic, or at least contradictory, in this exile, there wasn’t that much concern about his future, not really. His self-styled rehabilitation was not going to lead him to a life of good works. As a property who could generate millions of dollars for each appearance, the quality of the appearances notwithstanding, he was not going to be allowed to do anything beyond boxing. The economic imperative that such earning power represents overrides personal considerations (if, indeed, he had any) every time. There can be no resisting such opportunity.

Still, opportunities take many shapes; Tyson’s was in the form of that most American of ideas, the second act. Such rebirths are consistently doomed, but nevertheless popular. Who isn’t intrigued by a fresh start? Themes of redemption and recovery are very popular in a 12-step society such as ours, and though we like our heroes fallen, we also enjoy their comebacks. Even if it had been more or less predetermined that Tyson would reenter the fray, it was still going to be interesting to watch him do it.

Outside the prison on March 25, 1995, dawn began to break. There was a glint of sunshine on the coiled razor wire. You imagined some bustle inside as the most prominent member of the prison population gathered his belongings (all those books!) and made his farewells. But you couldn’t really know what was happening behind those walls. More black limousines slid back and forth across the prison entrance, disgorging more mysterious people. Everybody crunched back and forth on the gravel. It seemed you could actually watch time pass, the water towers beginning to leave their marks on the flat farmland. Standing at a window, Tyson may have enjoyed that same tracery of shadow, 1,095 times.

How would he make us pay for this, this interruption of life? This subtraction of it? Or, more cynically: Who would collect the tolls? The greatest intrigue on this cold morning was not whether he would fight or not, but whom he’d end up back in the ring with. His old promoter, Don King? The kid co-managers, John Horne and Rory Holloway? Would he return to his roots, reach back to the Catskills days and hire his former trainer Kevin Rooney to train him? Or would some wild-card promoter—and they all came to Plainfield, Indiana, to make their pitch, from convicted embezzler Harold Smith to former car salesman Butch Lewis—romance him away from all of that?

“At least half a dozen people, maybe more, think they have a chance to manage or promote Mike once he gets out.”

The media had gathered to watch, as if for white smoke from the Vatican, for clues as to the direction of Tyson’s future, investing this pseudodrama with significance of their own creation. The rumors in the weeks before his release were of such a conflicting variety that you almost had to lay them to some mischief on Tyson’s part. Butch Lewis said, “At least half a dozen people, maybe more, think they have a chance to manage or promote Mike once he gets out.” Bill Cayton, who had once managed him along with the late Jimmy Jacobs—Cayton was the remaining link to Tyson’s greatness—thought Tyson might want to go back to the Cus D’Amato era and retain Rooney, the Cus disciple who had trained him until 1988, when King got ahold of him and ousted the entire Catskills crew. Cayton believed that Tyson, from his jail cell, had made overtures to that effect, even though Rooney was then suing the fighter for $10 million for breach of contract.

Opinions elsewhere stressed the importance of Tyson’s getting a fresh start, the kind America likes, with fresh management. These opinions had been especially popular among alternate managers. If King hadn’t been the architect of Tyson’s ruin, the thinking went, he had at least been its landlord. What Tyson really needed was … Harold Smith, or Rock Newman, or Butch Lewis, or Bill Cayton. You could just ask them.

Tyson had entertained most all of them at prison, inspiring rumors of all manner of scenarios for his release. The King crowd had been similarly relentless in its courting of Tyson and would be presumed to have the inside track; still, there was a sense that Tyson was playing all sides from within those walls. It gave rise to much intrigue and not a little harrumphing from the King bunch.

Horne, a Tyson buddy who’d been installed as a sort of translator for the much older King, addressed the issue: “Every time somebody goes to Indiana to see Mike in prison, they come out swearing to God and to everybody else that they got him. When you’re behind bars, you’ll come out of your cell to see a jackrabbit if it came to see you.”

King, all the time insisting that Tyson would return to the fold and it would be business as usual, seemed more nervous about Tyson’s religious conversion than the possibility of a managerial change.

An insider who’d noted the strange stream of visitors to this prison more or less confirmed that. “Mike likes company,” he said. “It helps pass the time.”

Anyway, he said, it wasn’t like King didn’t understand his man. “No one is better in the world at getting into a fighter’s psyche.” It probably didn’t hurt that King was covering all bases, dropping by a Los Angeles auto dealer to pick up a $300,000 turbocharged Bentley as a gift for Tyson.

Religion was a wild card, though; King had overseen Tyson’s conversion from Catholicism to his own Baptist religion in a Cleveland church, and news that Tyson had converted again, to Islam, was not exactly a confirmation of the status quo. This spreading of religious wings was a small show of independence that, grown any larger, endangered their relationship. What was Tyson doing with a religious advisor, Muhammad Sideeq? Hadn’t there been a great heavyweight champion before whose religious awakening had heralded his passing into the control of Muslim management?

King, all the time insisting that Tyson would return to the fold and it would be business as usual, seemed more nervous about Tyson’s religious conversion than the possibility of a managerial change. His office debunked reports that the first thing Tyson intended to do out of prison was visit a mosque. For some reason, this became a persistent issue, as if any evidence of worship established a chink in their relationship. All these guys in their fedoras and bowties, they were worrisome to King. “Muslims,” he told everybody who asked, “make good visitors, too.”

At 6:00 A.M., among the odd comings and goings in the dimness of a Saturday morning, King himself produced a small excitement by climbing out of one of the black limousines and, with his minions Horne and Holloway, disappearing into the prison’s visitors’ center. It couldn’t have been unexpected, but there nevertheless was a thrill among the crowd as it hit home: The battle for Tyson’s life, maybe even his soul, had been no contest, a laydown.

Then, at 6:20 A.M., in the loneliness of a Hoosier countryside on a day that was turning gorgeous, a tall man holding his black leather overcoat open like a drape exploded from the door, and the same entourage that had entered before, but grown by one, rumbled through and into the waiting limousine. And that was that. Tyson, whose white skullcap reflected all the available light, was in the middle of the moving huddle, and it was impossible not to realize—a quickly arriving idea—that he was leaving jail with the same men who had delivered him there.

Postscript

It’s hard to imagine now, but even as recently as the ’90s, heavyweight boxing was an important sport in this country. Its popularity was certainly fitful once Muhammad Ali finally departed the scene, but whoever was champion at the time still commanded a good deal of attention. And none more than Tyson, who exploded onto the sport as this precocious predator, just blowing everybody up in a youthful and mindless aggression. Even after he got beat by Buster Douglas and was exposed as a one-trick bully, and especially after he raped a young woman and did prison time, he remained fascinating to the public. Maybe he wasn’t going to pan out as a heavyweight legend, but he was going to be fun to watch, self-destruction just around the corner. So it seemed obvious to me that his comeback, which probably wasn’t going to be important on its athletic merits, would at least be interesting. Don King, a tremendous horde of sycophants, a mewling cable company and complicit casinos—there wouldn’t be this much greed in action until the banking industry discovered the principles of the boxing business. There just had to be a story that would arise out of this cynical and largely demeaning exercise (I mean, Peter McNeeley?). Now, I didn’t know when I began the book that it would end in such a decisive moment of shame and humiliation. That was just a bonus.

Since each fight in this comeback was essentially a magazine piece, it didn’t take a lot of art to string them together in book form. But it wasn’t just an anthology either. The players provided all the narrative arc I needed, but still, there was definitely a narrative arc. I could see the larger story taking shape, fight by fight, tragedy looming all the while. Again, I could never have imagined it would arrive so abruptly. But I knew, I just knew, this wasn’t going to end well.

I never thought Tyson was a horrible person, even when he was doing horrible things. I thought he was more of a con man than boxer (although he was exciting enough there for a while). And I thought if he could somehow survive these violent and destructive impulses, which were obviously pathological but also heightened by youth and immaturity, he might one day become, well, even less horrible. And I think that’s what we’re seeing today. Maybe he’s wiser, I don’t know, but he’s certainly older and all those wild and unpredictable urges have been scaled down. I guess it’s interesting to see him trotted out for his one-man shows—here’s this guy that seemed to make our world quite a bit less safe, now talking about family picnics. And I’m glad he’s survived. But, man, for a while there, it was quite exciting, if a little unnerving, having him around.—Richard Hoffer

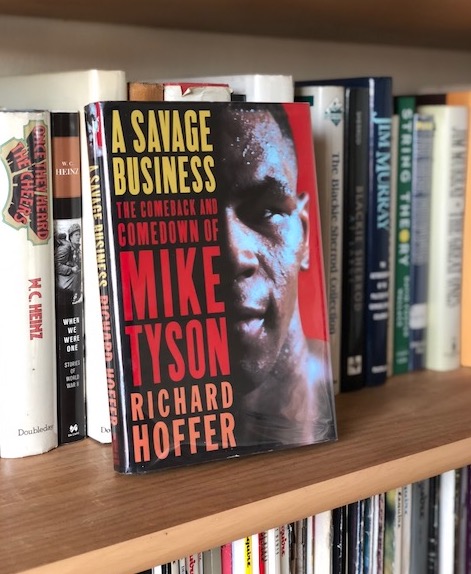

[Photo Credit: AB]