Arthur Miller is slouched in the drafty rehearsal hall on the top door of the New Amsterdam Theatre, on 42nd Street. Miller is tired to his bones. He lifts his round, black-framed glasses and rubs his eyes with his big, thick worker’s hands, over and over, and wonders if this play, this Death of a Salesman, this “poem,” as he has been calling it, will ever come alive. Right now it is as poetic as pea soup.

It is January or 1949, Miller knows that his play, as he says, breaks “every rule in the book,” that it is “special.” Stylistically, it is dreamy, floating out of real and remembered time; its themes are grandly ambitious, audacious. It aspires to Tragedy, though its hero is a lumpy loser. It is also what Miller calls a “social play,” a grand indictment of the American dream of success—a judgment that has been simmering in him since the Crash rudely woke everyone up. Miller has been under pressure from certain backers to turn the work into “a perfectly normal realistic little play,” and one has even taken his money out of the show. Miller is, at 33, a self-assured young man, but he is worried. Only four years have passed since his first New York play, The Man Who Had All the Luck, closed after four performances. All My Sons, which he wrote after he got his confidence back, was a success last year, but that play was a more conventional melodrama. He “seriously doubted” that Elia Kazan would want to take a chance on directing the new one.

“My romance with the audience lasted through 1949 only,” he says, and he is not smiling.

And now, for what have they both taken the chance? How can they tell if the play works or not when their lead actor is practically sleeping through rehearsals? Lee J. Cobb, who plays Willy Loman, has taken weeks to learn his part; he has been sluggish at every rehearsal, “sitting there,” as Miller remembers, ‘like a big tub.” If this goes on much longer, audiences will think that Miller’s poem is about the tragedy of narcolepsy. This is the first run-through Miller has watched.

Suddenly—Miller is not sure when it happened—Cobb, the slumbering giant has stirred himself. He is acting, beautifully. And by the middle of the second act Miller breaks down, “simply weeping,” as he recalls, “overwhelmed with grief, and with the exhilaration of knowing that all of us had done this thing, had given it life and made it fly.”

So Miller is assured, but he still has no idea how seismically people will be moved; this incident is the merest foreshadowing of what is to come. On opening night after the show, the playwright watches the audience leave the theater. They are dazed, saucer-eyed, as if they have all just seen a spook. One of these people is Bernard Gimbel, of Gimbel Brothers. Gimbel looks at Miller, tries to talk but can’t. “Utterly speechless,” as Miller recalls, “he Just kept walking, fell into his limousine, and rode away” (and, the next morning, sent a memo to every executive that no one was to be fired because he was growing old).

“I had no idea people would take it so goddamned personally,” Miller says now, in his raspy, Brooklyn-accented voice. He smiles suddenly—it is a wonderful smile, ear to ear, but unexpected on that chiseled face, like seeing a Mount Rushmore profile start to grin. “I was quite shocked. You know, ‘craft’ has two meanings, and one of them is ‘sinister.’ When people came out staggering, I felt… guilty about it.”

Thirty-four eventful years have passed since the crumpled, clownish, dumb salesman shuffled across the stage of the Morosco and won his creator a Pulitzer, a New York Drama Critics Circle Award, and an instant place in the pantheon of great living American playwrights. Miller had spoken to a national anxiety, had shown theatergoers their secret selves. Even the loftier critics—the ones who, like Eric Bentley, did not agree that Miller had written the great American tragedy, who charged Miller with abstracting the causes of Willy’s misery to the Success Myth, with writing a “social play”—had to concede the power of Salesman. Willy, wrote Mary McCarthy, “is a capitalized Human Being without being anyone, a suffering animal who commands a helpless pity.” Still, she said, “Death of a Salesman is the only play of the new American School that can be said to touch home.” Says Richard Gilman, who has been no fan of Miller’s on many other occasions, “You have no idea how deadly the theater was then. Miller and [Tennessee] Williams brought it to life.”

None of Miller’s other work has been as explosive, as embraced as Death of a Salesman—“My romance with the audience lasted through 1949 only,” he says, and he is not smiling; other plays have been more moderately reviewed. But he has continued to be the country’s most public—through his turbulent marriage to Marilyn Monroe, his refusal to name Communist-party members before the House Committee on Un-American Activities—and most durable playwright. Death of a Salesman has been translated into 29 languages and is required reading in high schools and colleges. In Europe, where his plays are hugely popular, professional touring companies have performed them continually for 30 years. Salesman is currently being staged by three European companies, and a London production was a long-running hit in 1980. In Australia recently, Salesman broke all box-office records for the country’s largest theater. The Crucible, Miller’s 1953 drama about the Salem witchcraft trials (and, by implication, the McCarthy inquisitions), was a hit two years ago in Peking, where audiences found ready parallels to the Cultural Revolution. Salesman, with an alI-Chinese cast, will play there this spring.

Miller, who is now 67, has been less successful, however, closer to home. The American Clock, his 1980 play about a Depression family, was panned by most critics when it opened on Broadway; The Archbishops Ceiling, about a dissident writer in an East European country, never made it to New York from its Kennedy Center run; The Creation of the World and Other Business, Miller’s Broadway comedy about the Book of Genesis, got skewered by every single critic. And 2 by A.M., a duo of one-acters at the Long Wharf last fall, got, as Miller put it, “really blasted out of the water” by reviewers. Nonetheless, next month Miller will try again for a welcome in the city that made him famous: A revival of A View From the Bridge will open at the Ambassador on February 3.

The original version of A View From the Bridge, a one-act play starring Van Heflin and Eileen Heckart, opened to moderate reviews on Broadway in 1955. It is the last of Miller’s early works—the last before his 1956 marriage to Monroe and his eight-year absence from the stage.

The play is echt Miller, complete with a little man as its tragic protagonist, a carefully observed New York patois (“Them guys don’t think of nobody but theirself”), preoccupations with man as a social creature, with the wages of guilt, with the sin of selfishness. Eddie Carbone, “as good a man as he had to be,” is a 40-year-old longshoreman living in the Red Hook slum section of Brooklyn with his wife and his orphaned teenage niece, Catherine, who adores him. Eddie adores Catherine as well, perhaps too much: Possessive, protective, he winces when he sees her in high heels, and warns her not to “wiggle” when she walks. All his dreams focus on Catherine’s making it as a secretary in a law firm. Instead, his wife’s two cousins, illegal immigrants, arrive from Sicily to stay with the Carbones and work on the docks, and Catherine promptly falls in love with the unmarried one, blond, pretty Rodolpho. After a scene in which the drunken Eddie, frothing with anger. kisses Catherine on the lips and then, in an attempt to prove to Catherine that her fiancé “ain’t right,” kisses him on the lips (out-of-town audiences still gasp at this), Eddie breaks the ultimate Red Hook taboo: He calls the immigration office and informs on the Sicilians. From that point Eddie is a walking dead man. Destroyed as a man, Eddie ordains his own death by getting into a fight he cannot win. “What kills Eddie Carbone,” Miller has written, “is nothing visible or heard, but the built-in conscience of the community whose existence he has menaced by betraying it.”

In a sense, all you really need to know about Arthur Miller is that he was thirteen in 1929, that the Depression hit his Brooklyn family smack in the face.

Miller modeled his play on Greek tragedy, using a narrator as the chorus, honing the plot to what he calls “a clear, clean line of… catastrophe.” The allusions to the ancient form seem obvious now, but the spareness of A View From the Bridge serves it well. The play is urgent, airless, and creepy from the start; you know that a downfall is imminent. As the play begins, says Miller, “the knives are being sharpened.”

The full-length Bridge, directed by Peter Brook, had a long London run: in 1965 Ulu Grosbard’s production helped launch the careers of Robert Duvall, Jon Voight and Susan Anspach. This version, with Tony Lo Bianco, Rose Gregorio, and John Marley, has already had an encouraging history. The Times gave it a rave when it opened last year at the Long Wharf, and audiences in Fort Lauderdale, where it has been running for several weeks, have given it standing ovations. “And the average age there is deceased,” says Miller, who is thrilled. “They usually spend second acts getting into their wheelchairs.”

In a sense, all you really need to know about Arthur Miller is that he was thirteen in 1929, that the Depression hit his Brooklyn family smack in the face. He watched the Bank of the United States close, watched the crowds of people standing at its brass gates, unable to get their money out, and knew the world was no longer a snug or predictable place. “No one,” he has said, “could escape that disaster.” Before the crash, he read Tom Swift and The Rover Boys, horsed around in Central Park; after it, he delivered rolls from 4:30 in the morning until school started. At seventeen, he was at work in an automobile-parts warehouse in Manhattan.

When the stock market collapsed, the family moved from a roomy, airy house to what Miller calls a “six-room shack.” He has always been sketchy, protective about his past; his sweet-tempered father lost all his money and became a salesman, but, says Miller, retained his dignity. The families in his works, however, are riven by hard times. Fathers are often shattered by the Crash; mothers become desperate, clinging to the son to “light up the world. That kind of a family,” he says, “is built on ever rising expectations—this year we’ll buy a house, next year we’ll buy a car. When the bottom fell out you really didn’t have anything. One of the myths about the Depression was that it brought everyone closer together, when it actually made everyone more voracious. Jesus Christ, there was anxiety.”

When the trauma of the Depression does not figure explicitly in Miller’s work—as it does in The Price and The American Clock—its presence is felt, just under the surface. Miller was made a grown-up by it overnight, and watched the grown-ups become children. The imperative of behaving honorably, responsibly, pervades all his work; so does maintaining a moral authority in the wake of disaster, a contempt for the System, the need to sacrifice the self for the greater good, to survive crises, spirit intact, and to prevail against despair.

The years have softened Miller, sanded down the sharp edges. He is not, by nature, a modest man.

Miller’s “kindergarten maxims,” as one critic calls them, have hardly won him the affection of the critics, some of whom have gotten downright wicked in their reviews of late. Watching The Creation of the World and Other Business, Stanley Kauffman wrote, “is like going to the funeral of a man you wish you could have liked more.”

What the critics disdain as moralizing arises from Miner’s attempts to explore real problems. “I am very old in the theater,” says Miller. “The last writer who I can honestly say influenced me was Eugene O’Neill—I’ll never forget seeing Iceman; I thought, ‘This is pretty great stuff. This is real grown-up theater.’ I have a problem with theater that is basically jokey. And I don’t like things that are adventitious, that come out of left field. I like to think there’s a process to life, a procedure we can’t describe but that exists, under the sidewalk.”

In Miller, this high seriousness has sometimes teetered into a kind of puffy self-importance. He is often described by those who have known him as a solemn, even priggish man—a reputation that wasn’t discouraged in the past by his carrying on in print rather windily about his own work (“Time is moving—we have a world to make”), or, sometimes, by the work itself, some of which was baldly preachy. In Marilyn (a book Miller detests; he still does not speak to its author), Norman Mailer gives this naughty, nasty sketch of the Miller of the fifties: “He … spoke in leftist simples. … His idea of himself after Salesman had become immense…. He was sufficiently pontifical to become the first Jewish Pope, he puffed upon his pipe as if it were the bowl of the Beyond.” A neighbor remembers a dinner party at Miller’s at which the host began the story of his life at cocktails and by dinnertime, hours later, “had only gotten as far as the bus trip from Brooklyn to the University of Michigan.” Miller was renowned for making cast members listen while he read the entire play aloud; even Harold Clurman, Miller’s friend and the director of several of his plays, once wrote that he tended “to expatiate to the acting company too elaborately, sometimes too intellectually, on the motivations of his writing.” Actors, he added, “are seldom stimulated as actors by this sort of exegesis.”

The years have softened Miller, sanded down the sharp edges. He is not, by nature, a modest man; “Arthur is a marvelous and extremely important writer, and the person who knows that better than anyone is Arthur,” says his friend the producer Robert Whitehead. But he is also funny and engaging and enthusiastic, and his grin is luminous. “He gets funnier as he gets older,” says Whitehead. “He sees the ridiculous and the tragic more, the highly comic quality of life.” “I think what has happened,” says Miller. “is that I’ve become less and less interested in making an arraignment and more and more interested in the balance of forces. We’re always patching ourselves together; life is a matter of exchanging one half-truth for another. We have to struggle, to absorb, the terrible impact of ambiguity.”

He is fond of anecdotes about people and things turned inside out; the critic who gave a scorching review to a play of his and years later congratulated him on its revival: an old Communist chum who has gotten rich in oil. ”I’ve been in conflicts so many times,” he says, “when points were battled to the death, and then the person is in front of you years later and you can’t remember what it was that was so goddamned important. We all change places; as you get older, you realize that this life is a minuet. We’re all in this dance together. Thera’s an absurdity to it; you have to laugh.”

Miller and his third wife, photographer Inge Morath, live on a hillside in Roxbury, Connecticut, in a big eighteenth-century white frame farmhouse (bought while he was married to Monroe, but not much lived in then; she didn’t cotton to the country). He takes a Brooklyn boy’s pride in playing the landowner, clomping around in work boots and a burly sweater and baggy pants, to point out the stand of trees he planted, the well just dug. The house is low-ceilinged, snug, filled with Month’s pictures, drawings and sculptures by Alexander Calder, their friend Robert Osborn, and their only child, Rebecca, a pretty Yale junior of whom he is hugely proud. “I’m told she has a really remarkable line for someone her age. She’s been selling her stuff, and not for peanuts.”

He and Morath have been married for twenty years; they have, by all accounts, a fine marriage. Austrian-born Morath is a merry, birdlike, phenomenally energetic woman (she taught herself Russian several years ago and has recently conquered Chinese), a foil to Miller’s restraint. “I left you money for the week,” he tells her as he goes off on a trip. “Goody, goody,” she says. The two are also successful collaborators—on three text-and-picture books—and traveling companions. They will both go to China this spring for Salesman.

Though “whole days go by where I don’t do anything,” Miller tries to write every day for five or six hours in the squat, one-room studio he built for himself some yards away from the house, it is plain, a little fusty inside. A few warpy books slouch against one another on the bookcase, together with a row of thick spiral notebooks filled with notes and diaries. A small Greek mask of tragedy hangs above his desk; on it are pages of a script for a new play—a “full-length, big” one he doesn’t want to discuss—crammed with scribblings and crossed-out lines. “And this isn’t even messy yet,” he says. I review endlessly. Sometimes I talk out the parts—I can wear my voice out doing it—and sometimes I just hear them in my head.”

“It sounds absurd now, but a lot of people were excited by the idea of a national theater company.”

Miller proudly points out that he is lucky to have friends who “have no connection to the arts at all—carpenters, businessmen, a pilot. They’re the evidence, not the commentators.” But he and Morath are also charter members of what a neighbor calls “the Martha’s Vineyard winter set”: They see the Styrons, Philip Roth, a handful of painters and writers. “These are my friends, we get together,” says Miller. “But I have no sense of intellectual community, none at all. It’s a habit of aloneness. I’ve really perfected it now.” Miller envies Lanford Wilson his creative home at the Circle Rep; the last time Miller tried to make a nest in the theater was when he, Kazan, and Whitehead helped create the Lincoln Center Repertory Company, and he is still sour about its failure. “It sounds absurd now, but a lot of people were excited by the idea of a national theater company. I thought we could get it to where it would be a real jumping kind of a place.” In gloomier moments, he conducts monologues on a longtime obsession, the disintegration of serious commercial theater in favor of high-priced soap-bubble entertainment. “I tried to do something about this years ago, when I was on the council of the Dramatists’ Guild. I had a meeting about it. I went over like a bomb. Mr. Shubert had a face like a wooden Indian. Now it’s all Dreamgirls.”

He is also a skilled carpenter. His house and apartment are stocked with tables and chairs and benches he has made. (“Tools, tools! All he wants for presents are tools!” says Morath.) The hobby, which he took up when he was six years old, suits him. Like his plays, the furniture is sturdy, well made, serves a purpose; like many of his heroes, Miller needs to work with his hands. Willy Loman, whose real skill is not as a salesman but as a carpenter, dreams of moving to the country and building a house there, “ ’cause I got so many fine tools, all I’d need was a little lumber and some peace of mind.”

The two public, theatrical events of Miller’s life came side by side, in one year, 1956: He appeared before the House Committee on Un-American Activities and became the husband of Marilyn Monroe. The events seem wholly incongruous—Miller playing the lover and Miller playing the man of conscience. In fact, in both his five-year marriage and his appearance he was doing, as he perceived it, his Duty, Both, in a way, are morality tales.

Miller was called before the publicity-giddy committee to explain why he had been denied a passport two years earlier. He appeared and answered their questions but did not name names. At that point, the committee was sheer farce. Its members offered Miller a deal: If its chairman could pose with Monroe, Miller might be let off the hook. “They were so incompetent,” says Miller, “like dancing elephants. They thought they were hot stuff, TV interrogators. It was awful, awful. I couldn’t remember half of what they asked me about, and I had no idea what questions were coming next. I was really sweating it out. I didn’t want to go to jail. But I didn’t think I had a choice. If I was working for a company and needed a paycheck I might have felt differently. But I was always fatalistic about being able to earn a living, as long as I had a pencil.”

Awful, yes—but Miller did have Monroe, whom he would marry only weeks later. Their courtship made Miller almost as famous as she; he became the hero of a romantic comedy, the owl to her pussycat. Some years later, while Miller was president of pen, a Nigerian poet who had been sentenced to death for insurrection came to his attention. With the help of an English go-between, Miller wrote a letter to Major General Yakubu Gowon arguing the poet’s case. Gowon read the letter and asked, “Was this the man who married Marilyn Monroe?” The Englishman nodded. “Do you think,” the general said, “that he would write me a personal note?” Miller did; the prisoner was released.

Miller tells this story apropos of something else; he does not speak of Monroe directly, not even to friends. He did, however, tell the story of their marriage in After the Fall, the explicitly autobiographical play produced two years after Monroe’s death (and directed by Kazan, whom Miller had forgiven for being a friendly witness). Jason Robards Jr. was Quentin, a lawyer; Barbara Loden, in a blond wig, doing an eerie imitation of Monroe’s flannel-soft, purry voice, was Maggie, the sweet, self-destructive singer who had been “chewed and spat out by a long line of grinning men.” It amounted to a racking confession, following Quentin as he pries pill bottles loose from Maggie’s hands, becomes her flunky, tries to “save” her, despairs. Except for The Misfits, Miller got almost no work done during the five years he was married to Monroe: he once said, “It was all I could do to take care of her.”

Miller was accused of sullying Monroe’s image, of exploiting her hair-raising anguish. Miller feels that this judgment tainted the reception of the play even before it opened, that the play has never been analyzed with a cool critical eye. “What people forget,” he says levelly, is that I stayed with Marilyn longer than anyone in her entire life. Anyone. I was with her for five years. She was,” he says, “a part of my life.” He discharged his responsibility, he was a good husband, “It is not a part of my life now,” he says, glancing out a window, “except when some stupid jerk says something about it.” He walks to the kitchen to wash a coffee cup. The subject is closed.

It is dusk and Miller is driving to Manhattan, where he will meet with a friend to show her the speech he has written on Vietnam, which he will deliver to a group of journalists in California (he has written the talk from notes he kept during the war; the pages are single-spaced, neatly typed, dated).

Miller, a fellow traveler a hundred years ago, says he hates to talk politics, but his conversation always circles around to it sooner or later. “Vietnam was the first war ever fought by Americans that wasn’t apocalyptic. No one believed we were making the world safe for the four freedoms.”

Miller’s war with the critics has made him cranky but resigned. He grumbles for a while—“I haven’t felt I’ve had any critical base since Clurman died. It embitters you to a degree”—then regroups. “Let’s face it, I write pretty damned good parts for actors, and the plays offer directors challenges. So even the plays that have been condemned have a life here and abroad. And I don’t live very badly. I’ve raised a lot of kids [he has a son and daughter by his first wife]. I never had to go to work in a paper-bag factory.”

Miller misses his turn to the Major Deegan and finds himself driving around the Van Cortlandt Park area of the Bronx. He has never been in this part of the city before. “Who would ever know this was here?” he says. He points to a row of brick and stucco houses side by side, bacon strips of lawn in front, their roofs tinged bright blue-green. “Now those, those were built in the thirties. See those roofs? Copper.” He seems pleased; Willy Loman could have lived in one of these houses, or Joe Keller, in All My Sons, with a huge Magnavox radio in the corner and Collier’s on the coffee table. After the Crash, Miller grew up in a house like this in the Midwood section of Brooklyn. He went back there some years ago, trailed by a film craw shooting a documentary on his life. “God, you can’t go home again. The whole neighborhood had changed: It’s mostly Italian now—they keep it nicer than we did—and there’s a Puerto Rican F.B.I. agent living in my house. No one remembered me. Finally, I hear this little voice calling, ‘Arthur? Arthur? Is that you?’ It was a lady I used to know, but it took me a long time to recognize her, to peel the mask of age off her face. She said. ‘Arthur! I knew you’d come back!’” And the playwright, who has, in a way, never left, throws back his head and laughs.

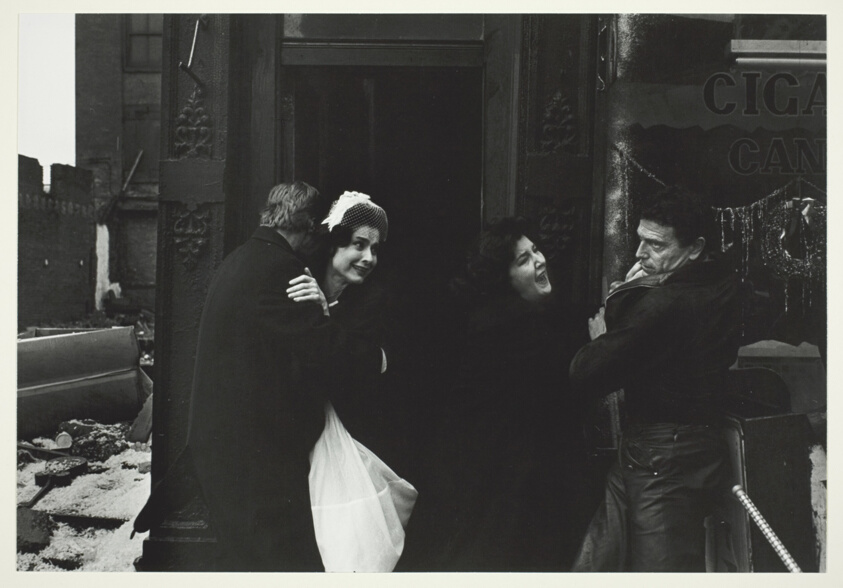

[Photo Credit: Inge Morath c/o The Art Institute of Chicago]