I was 22 years old and the first woman ever to cover sports for the Fort Worth Star-Telegram. Up until then, my assignments had been small-time: high school games and features on father-daughter doubles teams and Hacky Sack demonstrations. But now it was late September, and my editor wanted me to interview Mr. October about what it was like not to make the playoffs.

I’d heard the stories: the tales of women who felt forced to make a stand at the clubhouse door; of the way you’re supposed to never look down at your notepad, or a player might think you’re snagging a glimpse at his crotch; about how you’ve always got to be prepared with a one-liner, even if it means worrying more about snappy comebacks than snappy stories.

Dressed in a pair of virgin white flats, I trudged through the Arlington Stadium tunnel—a conglomeration of dirt and spit and sunflower seeds, caked to the walkway like 10,000-year-old bat guano at Carlsbad Caverns—dreading the task before me. It would be the last day ever for those white shoes—and my first of many covering professional sports.

And there I was at the big red clubhouse door, dented and bashed in anger so many times it conjured up an image of stone-washed hemoglobin. I pushed open the door and gazed into the visitors’ locker room, a big square chamber with locker cubicles lining its perimeter and tables and chairs scattered around the center. I walked over to the only Angel who didn’t yet have on some form of clothing. Mr. October, known to be Mr. Horse’s Heinie on occasion, was watching a college football game in a chair in the middle of it all—naked. I remember being scared because I hadn’t known how the locker room was going to look or smell or who or what I would have to wade through—literally and figuratively—to find this man.

It was mostly worn, ectoplasm-green indoor-outdoor carpeting—and stares. But on top of it being my first foray behind the red door, I was scared because of who I was interviewing: a superstar with a surly streak. I fully expected trouble. This was baptism by back draft, not fire.

But I couldn’t back out. In many ways, I had made a career choice when I walked through that locker room door.

“May I talk to you?” I asked Reggie, as everyone watched and listened.

He did not answer.

“Can I talk to you for a minute,” I said. Or at least that’s what I thought I said. I might have actually said, “Can we talk about how your face looks like one of those ear-shaped potato chips that the lady from the Lay’s factory brings on The Tonight Show once a year?”

Because his reaction to my question was to begin raising his voice to say, “There’s no time.”

“Is she supposed to be here?” he demanded. “You can’t be in here now.”

He still didn’t answer my question directly.

“Are you going to talk to me or not?” I asked.

A simple no would have sufficed. But instead, the man who is an idol to thousands of children launched into a verbal tirade loudly insulting my intelligence and shouting for someone to remove me from the clubhouse.

Here I was in my white flats, some fresh-out-of-college madras plaid skirt, one of those ridiculous spiked hairdos with tails we all wore back then, and probably enough add-a-beads to shame any Alpha Chi.

And there was Reggie, in nothing but sanitary socks.

His voice was growing louder. Mine, firmer.

Now almost everyone had stopped watching football and was watching me and Reggie. “Is she supposed to be here?” he demanded. “You can’t be in here now.”

“Are you going to talk to me or not?” I asked one more time interrupting.

He wouldn’t answer.

“All right, heck with it then,” I said. I spun around and walked out—past the staring faces, through the red door, down the 10,000-year-old bat-guano tunnel—and emerged into the dugout and the light of the real world, where I was nothing but a kid reporter who didn’t get the story. It was the last time I would ever try to interview Reggie. And it was my first failure covering sports. But it wouldn’t be my last.

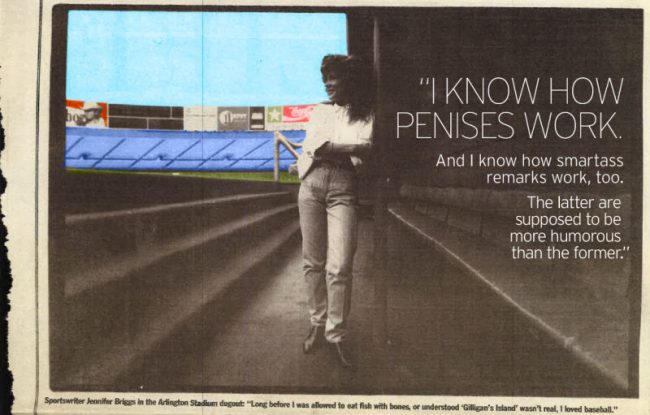

Long before I was allowed to eat fish with bones, could go all night without peeing in my bed, or understood Gilligan’s Island wasn’t real, I loved baseball. It’s the reason I’m a sportswriter, and I learned it from my dad. Back then, almost 30 years ago, passion for the national pastime was an heirloom fathers passed to their sons. But a little girl with blonde pin curls somehow slipped into the line of succession. I don’t have a radio talk show yet, but I now make my living writing about sports—at the moment, mostly the Texas Rangers. Covering major league baseball fulltime is my goal.

I’ve wanted to write stories about baseball since I was 10 years old—to write words so good that people would read them twice.

Career ladders are never cushy for anybody, man or woman, unless of course your dad is president of GM or GE or whatever Nation’s Bank is called this week. My dad was a buyer for Better Monkey Grip Rubber Company, and I’m not complaining. But the road has been anything but smooth. Family trips in an eggshell-white Impala to see the cousins in Plainview took fewer rough turns.

I’ve wanted to write stories about baseball since I was 10 years old—to write words so good that people would read them twice. I used to write Dallas Cowboys columns in blue Crayola on a Big Chief tablet in the part of my sister’s walk-in closet I had designated as the press box. Bell bottoms hung over my head as I berated Tom Landry for not getting rid of Mike Clark or praised Roger Staubach the way little kids now get all slobbery over Nolan Ryan.

I never told my friends. I always won the big awards in elementary school, went to football games, and performed in talent shows. What kind of a goob would they take me for if they knew? But after getting home from school, I’d quickly skip back to the sports section of the evening Star-Telegram to compare my work to that of the pros. Sometimes I’d turn the sound down on the TV and try to do baseball play-by-play, too. I can look back now and see I was sunk early, my heart hopelessly immersed in a severely codependent relationship with a kids’ game played by grown-ups.

It began when I was 3 and my daddy took me to Turnpike Stadium—now Arlington Stadium—to see the old minor-league Spurs. We lived in Arlington, about five miles from the ball park. He carried me to the back of the outfield wall and climbed the slatted boards with his right arm and clutched me in his left. Then he held my head over the top of the wall in center. And there, not 1,000 days after I had emerged from the darkness of the womb, hundreds of bright light bulbs made me squint as I watched the first half-inning of my life, the last three outs of a Spurs game.

All I remember is green and light and the security of my daddy’s arms.

There were nights in the stands, too, where, just so I could enjoy the game more, my daddy patiently tried to teach the basics of scoring to a child not yet versed in addition.

We were a middle-class family of four with one kid just a few years from college and another a few years from kindergarten. We never wanted for anything we really needed, but my parents, raised in the Depression, were cautious about spending.

Buying ball tickets to as many games as my dad and I wanted to see was out of the question, so we climbed the wall in the late innings or sat in those free grassy spots behind the Cyclone fence.

There were nights in the stands, too, where, just so I could enjoy the game more, my daddy patiently tried to teach the basics of scoring to a child not yet versed in addition.

One night in the stands, I had my Helen-Keller-at-the-well experience. Suddenly it all made sense: the way the numbers went across in a line on a scoreboard, what the three numbers at the end of the nine meant, even why the shortstop didn’t have a bag. “He just doesn’t” was suddenly sufficient and I knew a grown-up secret, like writing checks, making babies, or reading words.

My daddy and I saw our first major-league game together on Opening Night here in 1972. Some summers we went to 20 games; others we went to about 56.

Sometimes we’d just watch any game on the TV. Other summer nights we sat on the back porch and listened to the Rangers on the radio. If my mom made us go to Wyatt’s for supper, my father would wear his primitive Walkman through the serving line, once scaring the meat lady by hollering, “Dadgum Toby Harrah!” when she asked if he’d like brown gravy or cream.

He’d pull me out of school at lunch once a year to go to the spring baseball luncheon and take me to games early so I could collect autographs. The balls with the signatures still sit on my mantel, most reading like the tombstones of major-league also-rans.

When I was 14, I heard from a friend that the Rangers would soon be hiring ball girls. The rumor was bogus, but it planted an idea. I began a one-kid campaign to institute ball girls at Arlington Stadium as well as to become the first.

I wrote management repeatedly. The executive types weren’t too hot on the idea. So when I was about 16, I wrote every major-league club with ball girls and asked about the pros and cons. I sent copies of their responses to the Rangers’ front office. I corresponded with them for another two years before the call finally came.

They were trying ball girls.

They picked three—Cindy, because she was a perky cheerleader at the University of Texas at Arlington; Jamie, because she had modeling experience; and me, because I was a pest.

We shagged foul balls, but in retrospect, I guess we were more decorative than functional. They used to have us dance to the “Cotton-Eyed Joe” in the seventh inning, and for a while we shook pom-poms during rallies—acts I now, as a baseball purist, consider heresy. But hey, I was the center of attention on a baseball field; I could sell out for that.

The next year, I was booted because I couldn’t do back flips.

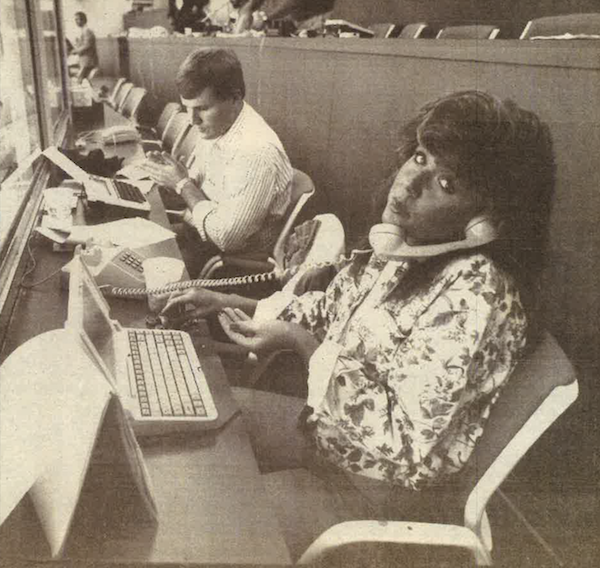

But by then I had gotten to know the sportswriters and broadcasters, and the Star-Telegram offered me a job—in sports—typing in scores and answering the phone.

I dropped my plans to go to the University of Texas and study broadcasting. I had enough natural talent, I felt certain, that with one high heel in the door, I could work my way into a writer’s job—maybe even someday cover baseball.

The realities of the corporate world and the attitudes of Texas high school and college coaches quickly clouded my idealistic vision of a quick ascent from 18-year-old ball-girl phenom to big-league ace baseball writer.

You see, folks in the world of sports weren’t used to working with a “fee-male.” And you know, they all say that word so well.

I started out in the office, taking scores on the phone and taking heat from the guys. Writing this the other night, tears filled my eyes, and I got that precry phlegm in my throat. I was surprised to realize that some of the wounds still hurt.

It wasn’t Reggie or pro-locker-room banter.

It was an area high school coach who routinely tried to get me to drop by his house when his wife was out of town; when I refused for the third time, he refused to provide any more than perfunctory answers to my story questions.

I have complained little through the years because the last thing I ever wanted to do was to single myself out from the guys. I didn’t want to be branded as some woman on a crusade.

It was when all the guys were inside doing interviews, and I was standing in the rain, makeup peeling, outside the high school locker room at Fort Worth’s Farrington Field, waiting beneath the six-foot-long “No Women” sign for the players to come to the doorway. It was walking into the football locker room at the University of Texas in Austin and having a large man with burnt-orange pants and dark white face pick me up by my underarms and deposit me outside the door.

God, I hate making a scene.

I have complained little through the years because the last thing I ever wanted to do was to single myself out from the guys. I didn’t want to be branded as some woman on a crusade. I’ve never been on any campaign to debunk the myth that testicles are somehow inherent to a full understanding of balls. I just wanted to cover sports.

But much of the early abuse came from the place I least expected it—my own paper.

Like a lot of kids starting out, I’d do office work all week and help cover games on the weekends—anything for a chance to prove my worth as a sportswriter. During my first four years at the Star-Telegram I took one day off to model at an auto show and five days off to get married. Those years were perhaps the most trying. There was a sports editor who would stop by every time he saw me eating, stare at me, and say in all seriousness, “Jenn, if you get fat, we won’t love you no more.” I could see my worth resided within the confines of a B cup and size six jeans. I wanted to cry each time he said that.

The guys screamed at me and demanded to know if I was “on the rag” when I was surly; yet they could scream and be surly at me all they wanted.

“Jenn,” he asked, “do you want to be treated like an 18-year-old kid or a woman?”

One editor in the chain of sports command kept trying to get me to check into the Worthington Hotel with him after work. Another superior had his assistant let me off early so he could be waiting for me in the parking lot.

He said he wanted to talk. I got in the car.

“Jenn,” he asked, “do you want to be treated like an 18-year-old kid or a woman?”

At first, I thought he meant on the job. He meant on the bed.

I never went near a bedroom with any of them, but I told him “a woman” because I didn’t know how answering “18” to this loaded question would affect my precarious career.

I was quite confused. My most innocent comments were greeted with sexual innuendo. I’m no wimp; I can take a lot. I know people make sexual comments to one another, and they are not always inappropriate. But this was something else.

All the culprits are either long gone or have actually apologized, saying they just didn’t know better at the time.

But how was I supposed to do my job with all that crap going on? I had to think as much about how to handle the next unwanted advance or suggestive quip as I did trying to figure the Mavericks’ averages.

Some readers had similar problems accepting a woman. I can’t remember the number of times I’ve picked up the phone in the sports department, answered some trivia question, and, when the answer didn’t win the guy a bar bet, had the caller demand, “Put a man on this phone.” Some simply called me a “stupid bitch” and hung up.

I know they don’t know what they’re talking about. But the remarks still hurt.

For years I was hopelessly mired in phone answering and score taking, watching as others in similar positions moved up and on. Once, after they’d let me try my hand at writing for a year or so, editors told me I’d never make a writer. I was creative and funny, but I just couldn’t write, they’d concluded. So I didn’t write. For eight months, the editors refused to assign me any stories.

I was close to giving up. I seriously considered taking a job as a researcher for a law firm.

But one thing kept me in sports: I got a Rangers media pass every year. It was the lonely thread that tied me to my game.

In the arbitrary world of newspaper politics, the arrival of a new sports editor breathed life into my career. I began investigating the pay-for-play scandals of the Southwest Conference. I broke several stories, one of which won a national award for investigative sports reporting.

I remember hiding in a tree outside a North Dallas bank waiting for an SMU running back because we had heard this was where he picked up his money. Then there was the time we had a story about an SWC coach paying players, and I appeared one morning at the school where he was an assistant. Tipped off to my presence, the coach broke into a near run when I headed toward him in the hall. He ran into a dark office where I found him hiding under the desk.

Hey, this is pretty cool, I thought. When you’ve got dirt on them, all the condescending good-ol’-boy stuff goes out the window.

I was actually in charge.

An SMU booster threatened to have my legs broken—and I was delighted. That’s something he’d say to anyone, I realized.

While all this was going on, I began helping out with Dallas Cowboys sidebar articles and weekend coverage of the Rangers. I helped cover the team for the Associated Press.

And I was entering the peak of a seven-year stint as the masked wrestling columnist Betty Ann Stout—Fort Worth’s equivalent of Joe Bob Briggs—whose unofficial duties included opening appliance stores, riding elephants when the circus came to town, and acting as rodeo Grand Marshal on the backs of large, hoofed animals.

Oh sure, little stuff happened, like the time one of the Oakland A’s made a big point of standing next to me naked in the middle of the clubhouse or one of the Los Angeles Raiders chucked a set of shoulder pads at my butt.

Then there was the occasion Rangers manager Doug Rader spat corn on me after I asked a dumb question. Of course, Rader would have spat corn at anybody.

The players didn’t know I’d grown up with games or that my best friends had usually been crude guys or that I could open a beer bottle with my incisors or that I liked to fish as much as they did.

By then, I had become accustomed to the nudity and byplay of the locker room. I’ve always considered the real hurdle of all this to be players’ perception of me, not suppressing my thoughts. Before a team got used to me, there might be some giggling each time someone made a smart remark or cursed loud enough to get you kicked out of the Watauga Dairy Queen.

The players didn’t know I’d grown up with games or that my best friends had usually been crude guys or that I could open a beer bottle with my incisors or that I liked to fish as much as they did. They didn’t know, and it made me feel awkward that they didn’t know that this stuff really didn’t bother me outside of the fact that I felt obligated to respond with a remark, which took away from my ability to do my job.

I was nervous the first time I entered the Rangers locker room, about seven years ago. Not about naked bodies or about crude remarks but about how they would think I felt—and how I intended to respond with confidence, no matter what happened.

So I stepped down the tunnel from the dugout to the clubhouse and peered around the open door.

The first thing I saw was four guys in a big shower.

Because of my vantage point, it appeared I would have to walk through the shower, through the four wet, naked men, to get to the actual locker-room area. I retreated back behind the door before anyone could see me.

God, I can’t believe someone didn’t warn me, I thought. And what if someone saw me in this state of trepidation? It was critical no one smelled fear or I’d lose respect from the get-go.

Maybe I didn’t belong here. Maybe I’d never fit in. Maybe I should write news or features because I’ll never have the fortitude it takes to stay on your toes with one-liners and be tough enough to handle this.

Maybe McDonald’s was hiring. But I had a deadline. I had to go in.

I wasn’t afraid of naked men. I was afraid of the unknown. A few feet in, I realized a hall ran in front of the showers. You take a right turn before you have to walk straight into the naked men and the soap.

The first Ranger I interviewed was drying his stomach with a towel. Before I could utter a word, he said, “Wait, let me rub it, it will get hard.”

Nudity rarely bothered me, but I prefer never to see Nolan Ryan in anything but Ranger white or blue jeans.

That seemed like such a dumb thing to say. I mean, I know how penises work. And I know how smartass remarks work, too. The latter are supposed to be more humorous than the former, though adulthood has taught me different.

I’ll always remember that no one else laughed, for whatever reason, and that made me feel good.

So I went about my business. I asked my question; he answered.

I should have told him how sad it was that he had to rub his own.

Nudity rarely bothered me, but I prefer never to see Nolan Ryan in anything but Ranger white or blue jeans. I have no idea why, except that Nolan Ryan and my daddy are my heroes, and I just have no need of seeing either one of their white heinies.

About 1986, there was a college football convention in Dallas. There were reporters all around the lobby of the downtown Hyatt, waiting for coaches to arrive after a golf game. I was leaning against a post, waiting for Grant Teaff, holding a notepad. That’s when a security guard came up to me to ask why I was there. I told him. He told me I had to leave unless I was staying at the hotel. He could not allow me to bother the guests.

I explained again that I was a sportswriter waiting for Grant Teaff and pointed out other reporters, all men, around the lobby. He said I was loitering. I refused to leave. He said he would have me thrown out physically.

“Do you think I am a prostitute?” I asked.

“That’s possible,” he replied. “I don’t have any idea what you’re up to.”

Mortified, I pondered my attire (a baggy smock top and pants). We both approached the front desk, where the clerk sided with the guard, saying I could remain for 10 more minutes, but only if I stayed out of the central lobby and remained “mobile.” No sitting or leaning. Each time I stopped pacing, the clerk and guard started toward me. I’d had enough. Once I stopped and they looked up, so I started spinning around in circles.

When the coveted Rangers beat came open, I was passed over. My dream of covering professional baseball seemed further away than ever.

That did it; now they were ready to call the police. I went home and called my sports editor. He got an apology from the Hyatt; I got suspected of prostitution while waiting in a hotel lobby for Grant Teaff.

About 1987, I got crossways with the sports editor. I ended up covering minor events full time, even doing the dreaded office score-taking work again. At the same time, my marriage began taking ugly, unspeakable turns. I began to wonder, what had I done with the last seven years of my life? Had all that I’d put up with just been for nothing?

When the coveted Rangers beat came open, I was passed over. My dream of covering professional baseball seemed further away than ever. And I didn’t want to go back to putting up full-time with condescending high school and college coaches and jerks guarding locker room doors.

I began experiencing panic attacks and became practically addicted to the anti-anxiety drug Xanax, buying it from bartenders and acquaintances when my prescriptions ran dry. My face broke out. And I gained 40 pounds.

Good God, all I had wanted to do was cover sports. The bouncing, wide-eyed ball girl who wanted to write about baseball more than anything was gone, abandoned in increments on football fields, at locker room doors, in editors’ offices, and on barstools. I had become a sweating mass of raw nerve endings.

I felt like a cancer victim who was finally ready to give up the fight because it meant giving up the pain and humiliation.

The dream was dead.

I went to features.

They gave me all the weird stories. They knew I could write even the most boring stuff into something of interest. But I learned to do news as well. I wrote about civil rights issues and roamed through abandoned warehouses alone in search of skinheads.

Yet all the time I was still dreaming up stories to get me to the ball park. A feature on the woman who washes the Rangers’ clothes was not out of the question. A three-part series on Ruth Ryan, spouse of Nolan, turned into a delightful three-week chore that included stops at the Ryans’ ranch in Alvin and the stadium.

I had started wandering longingly over to the sports department, just to talk about baseball. More than two years ago, I told the sports editor I wanted to return to sports. And I wanted to cover the Rangers someday.

I concluded my sports hiatus last year with a stint on a special projects news team, collaborating with another reporter on a series about Fort Worth’s high infant-mortality rate. We won some awards, and I gained some confidence and perspective. When you’ve interviewed a 17-year-old mother whose daughter was stillborn for lack of prenatal care, how tough can it be to talk to a young pitcher who’s lost to the Angels for lack of run support?

It was time to go back to the dream. I asked for—and received—a transfer back to sports.

In my three years away, I’d shed a husband, a house, a lot of weight, and a collection of unhealthy habits. I began bicycling and training for a marathon. Fueled by my own version of a life-affirming experience, I felt as though I was taking back 10 years of my life.

I was ready once again to be the greatest sportswriter who ever lived.

I was in the visiting clubhouse waiting to interview one of the Oakland A’s this year when one of the players called, “Here, pussy”—as though he were calling a cat. But of course, he hadn’t lost Fluffy; he’d found a woman in his locker room.

It doesn’t make me angry anymore; it just seems silly and absurd. But some paranoia lingers. Sometimes I’m kind of quiet in a group interview, and I have this feeling other reporters will think it’s because I’m a dumb ol’ girl.

Sometimes I will request an interview at someone’s house, and my peers act as though it’s weird. But how can you really profile a guy if you haven’t seen his coffee table or the junk stuck to his fridge?

I’m a general assignment sports reporter now, which means I do whatever they ask of me. My aim as a writer is to make the people I cover seem human to the readers. You can’t do this without asking about their dogs and their mom and what bugs them even worse than dropping the soap in the shower. It seems logical to me. I mean, we know a guy is probably happy to be a number-one draft choice, but what makes him real is how he is like or unlike us. It’s the way we measure all people, the Homo sapiens equivalent of sniffing butts by the fire hydrant.

But I don’t think it seems very logical to some of the other reporters. Sometimes I will request an interview at someone’s house, and my peers act as though it’s weird. But how can you really profile a guy if you haven’t seen his coffee table or the junk stuck to his fridge?

Sometimes before the game when everyone is milling about, I go sit around the corner in equipment manager Joe Macko’s office and visit for a while just so I don’t wear out my welcome in the room o’ nakedness. Some nights I walk out the back door where all the wives are waiting, and they stare at me strangely, as though they think I’m the woman Cosmo warned them about or something.

After a long game, while standing in the middle of the clubhouse waiting for someone to appear, I sometimes gaze off in one direction, the way you stare when you’re bored and become transfixed on an object until your eyes cross and you snap back into the reality of car payments and cellulite. I was doing that one recent day when a wet, naked body walked into my trance. It might as well have been a water cooler. I had to remind myself that I should probably look away.

That’s another thing that has changed. I really want to be as unobtrusive as possible, so I will turn away from someone who is dressing or, if I have the time, wait until he has put his shorts on before I approach. I’ve been around long enough now that if they see me turn away, they probably know it isn’t because I’m scared or intimidated. I like to think I’ve earned a little respect.

The Mavericks pose an entirely different set of problems. I’d actually never been in an NBA locker room until last winter. Then, just as I walked in the door, it struck me that I was five feet, three inches tall—about the height of an NBA crotch.

Point guards became my instant favorites for those early post-shower interviews. It is one thing not to look at your notepad, but another not to be able to look straight ahead without a big clothesline of boy parts.

James Donaldson was the very tallest, and I almost always waited until he had some small piece of fabric on before I walked back there. If necessity of deadlines or getting to someone before another reporter called for it, sure, I’d talk to Oral Roberts’s 900-foot Jesus naked, no matter where the crotch fell.

But you try to walk a fine line.

The Mavericks were a delight to be around even when pissed off. The Rangers treat me like anyone else who wanders in.

Oh sure, they may actually think I’m an idiot. But there’s a strange sort of comfort in feeling that if they think I’m an idiot, it’s probably not because I’m a woman but because I’m just acting like an idiot.

The most puzzled responses to my job come from the friends and acquaintances in my personal life. Kids at the tanning salon want to know if I date the players. Friends at Bible study ask if the players are mean to me. And then there’s the guy—almost any guy in any bar in town—who subjects me to a sports-trivia quiz during the usual getting-acquainted foreplay.

It usually goes about like this:

Leaking testosterone and reeking of beer, a Jethro Bodin-esque character sidles up and asks what I do.

“A sportswriter, huh? So do you know about sports?” (I’m serious, they really ask this.)

“Hey, if you know so much about sports,” he continues, “let’s see if you can answer this question: Who was the last NFL running back to also play quarterback in an even-numbered Super Bowl?”

I falter, and he complains, “Hey, I thought you said you knew sports.”

Lately I’ve just started saying I’m a secretary at Wolfe’s Nursery. But unfortunately, in north Arlington, this seems to be an enviable attribute on a par with big Dallas hair and coaching shorts as after-five wear.

And of course, women everywhere want to know about that great walled fortress of wet boy flesh, the locker room.

And you won’t believe this, and I swear it’s true: the immediate response of three women who don’t even like sports outside of bungee jumping at Baja is, “You’ve seen Ro Blackman naked?”

We’re sitting around the salon one day making bets on when the rest of the country will catch on that Ross Perot is a weasel when someone says he finished ahead of Bush and Clinton in another poll. Cindy, who is dabbing brown goop on my roots, figures this is like when the seniors get all reactionary and vote in the ugliest girl for homecoming queen, and it just might happen on a bigger scale.

Donna doesn’t like politics, so she asks what it is I do for the paper again. Donna doesn’t like newspapers either. Donna is a good argument for euthanasia.

The immediate response is curiosity: Do I get to go in the locker room?

Well, yeah.

So you’ve been in the Mavericks locker room? Yeah.

And you won’t believe this, and I swear it’s true: the immediate response of three women who don’t even like sports outside of bungee jumping at Baja is, “You’ve seen Ro Blackman naked?”

Well, I guess I had; I wasn’t sure.

I’m sure he’s been naked in the room where I was at some time. But the point is that you don’t even think much about people being naked after a while, and unless you have some peculiar reason for remembering, you don’t know who you have seen naked because they all kind of waltz in and out of the shower naked, just one wet butt covered with soap film after another.

I tried to explain that it is probably a lot like being a male gynecologist: the daily procession of personal parts becomes so routine that it ceases to be of anything but professional interest.

Yet I wonder. When men gather at bars and golf courses and any of the other traditional salt licks for male bonding, do they ask the gynecologist what Mrs. Holcombe’s hooters look like? Do they want to know if it’s hard for him to keep his professionalism with his hand inserted in some babe’s bodily cavity—and whether it’s scary?

I doubt it.

Donna persists.

“I can’t believe you are not in love with these men,” she says, biting her cuticle. I try to explain, which is difficult because Donna and I are on different sexual wavelengths. But then Donna likes the men she meets at Baja.

If I did ever fall hopelessly head over heels for one of these men, it would not be because I had noticed a pterodactyl-size penis, but for the same reasons I’d fall for anyone else.

Like many people, Donna, who should have been named Brittany, just can’t accept this.

“OK, you mean you’ve talked to Troy Aikman, and you didn’t notice what a hunk he is?”

“Well, I have talked to Troy Aikman,” I say, and one woman bites down hard on her blow-dryer and rolls her eyes as though she’s just gotten the high school quarterback in spin-the-bottle.

Actually, I tell them, one of the most peculiar side effects of my job is that it seems to run off men in personal relationships. Oh sure, at first they think it’s pretty cool that you’re the only person at a party who can remember Neil Lomax’s name or that you can name all the Rangers managers in 18 seconds—with a shot in your mouth.

The dirty little secret I’ve discovered is how little men know about sports, since this is what men are supposed to know more about than women.

But that’s while they are still trying to maneuver you quickly into bed. During this phase of courtship, most men would be reassuring Lassie that her role as a dog star doesn’t matter that they just like her nice, shiny coat.

For most of the guys who hang around for more than three dates, my job suddenly becomes a problem. Apparently a guy has to be awfully secure not to be intimidated by my frequent trips into locker rooms (as though I’m doing comparative shopping) or by my knowing a good bit about sports.

I can’t tell you the bizarre arguments I’ve had with a few of these creeps who keep suggesting I become a teacher. Or go back to feature writing. Or maybe into public relations. One even said, “You know you don’t have to do this work,” in a tone that sounded like Sting telling Roxanne she didn’t have to put on the red light.

The dirty little secret I’ve discovered is how little men know about sports, since this is what men are supposed to know more about than women. Most of the men I’ve dated certainly don’t know about the social fraying of America or why it might be at all amusing that a guy named Fujimori is in charge of Peru, so you’d certainly hope they knew some inane facts about NFL rushers. All most know how to do is bitch about the Cowboys and Mavericks and Rangers—about their (a) record, (b) salaries, (c) coach or manager—and praise the “kick-butt” barbecue they make before watching 18 hours of football on Sundays. That’s before they tell me I don’t have any business in the locker room.

I have assimilated to a large degree but probably never will completely.

I can’t understand the idiots who call the sports department and want to talk to a man on the phone instead of me—or some guy who goes out of his way to spit Niblets on me. But I can understand the athletes being naturally uncertain what to make of women, of me.

Many of the women they’re around—other than the reasonably stable ones like their wives and mothers—are groupies. I understand that uniforms—unless they say, “Eb, your man who wears the star” on the lapel—are a great aphrodisiac in contemporary culture. I admit, some days even the UPS guy looks awful good.

Yet anyone who gets self-worth through random sex with a professional athlete is not exactly MENSA material. So you’ve got all these big-haired babes who think the electoral college is a beauty school, ready to hoist their miniskirts for the first athlete who comes along. And then you’ve got this woman who comes in to interview them, maybe with big hair and a short skirt too, depending on the humidity and what’s off at the cleaners that day.

So why are they going to think the reporter is any different at first? Logic says they might not. So I remain cautious, probably overly cautious, about appearances.

If I ever dread talking to players now, it is not because I feel that I don’t belong there. It is because it doesn’t seem that any reporter should be there.

For instance, there are things I might say to a friend or even a casual coworker that I wouldn’t think a thing about, but I stop short of saying such things to the players. Like the other night when I was interviewing Kenny Rogers after the game, and I just happened to notice he had really healthy-looking hair. The hamster in my mental Wonderwheel never seems to stop running, so my mind keeps a lot of thoughts going at once. So while I’m asking him about his family’s strawberry farm, I’m wondering if eggs have given him this nice, shiny coat or if he uses his wife’s conditioner, and if so, what is it?

I almost said matter-of-factly, “You know, Kenny, you’ve got a fine head of hair.” I stopped myself because he might not take it right. He might not understand that I meant its thickness and shine were enviable.

There are a lot of times I want to compliment a player or make a personal observation, just because it’s my nature, but my nature has to change for a moment because I don’t want anyone to get the wrong impression about my intentions.

If I ever dread talking to players now, it is not because I feel that I don’t belong there. It is because it doesn’t seem that any reporter should be there.

One of the most sickening feelings I get is when I have to go interview some pitcher who’s been shelled or some guy who is struggling at the free throw line or a coach who is on the verge of not being a coach. I hate to invade their pain and their anger and sometimes even their happiness. What does it really matter if the rest of the world knows? I think about what it would be like to have them asking me every day, “Well, how about that really thrown-together graph there at the top?” or “You wrote a good piece, Jenn, but then your headline writers let you down at the end; what does that feel like?” or “You haven’t written any good stories in the last month. Can the slump be permanent?”

Man, I’d hate them.

No less than two or three times a home stand, the feeling hits again—almost always as I walk down that tunnel from the upper deck that spits you out in back of home plate. It’s just before batting practice, about 4:30 p.m. The TCBY people are pouring half gallons of yogurt stuff into the soft-serve machines; a guy is sweeping up peanuts in three-quarter time. I think how cool it is to watch a stadium yawn to life. Last night’s trash still blows, even though people are sweeping all over the place. It reminds me of a debutante waking up in last night’s party dress, reeking of beer.

About two yards down, I see legs behind the batting cage. Someone has come out early for batting practice. In a few more feet, the torsos appear and the warm breeze melts around my face. Near the field, I can see it is Al Newman and somebody. Always Al Newman, and he’s always smiling because he’s kind of happy to be here too.

The grass spreads out in the shape of a precious gem, and there are fans here and there who have come to see batting practice just because it’s relaxing. Then it hits me: My job means I get to be around this game and write about it. And it’s OK to spit your sunflower seed hulls on the floor. I head down the steps, past the seats where I couldn’t even afford to sit when I was a kid, open heaven’s gate, and walk onto the field.

Sometimes I take a seat in the dugout, where a few of the guys are filtering in, grabbing bats and bubble gum. For a minute, before I start to work, I smell the bubble gum in the breeze and look at the kids leaning over the dugout and the boys of summer in it.

And every once in a while I think about slatted billboards and a daddy’s arms.

The other night, there were two girls in the clubhouse after the game. They were reporters and looked young enough to remind me of my old days—except they weren’t wearing white flats.

No one did or said anything off-color. But there were a few giggles. And a few guys maybe flounced around a little more just for brief amusement. Quite normal, nothing harmful.

I mentioned this to someone later.

I noted being in the middle of the room when a player came out of the shower, spotted me, and turned around and went back in. A few minutes later he came back out wearing a towel.

By now I wouldn’t really notice if he’d worn a towel or hadn’t. But it struck me that something had changed: that my presence was no longer cause for flouncing; that I’d somehow earned this strange sign of courtesy and respect.

“Jenn,” my friend told me, “I guess you rate a towel now.”

[Featured Image: Jim Cooke; original photo by Scogin Mayo]