Observe, please, the human skeleton, 208 bones perfectly wrought and arranged; the feet built on blocks, the shinbones like a Doric column. Imagine an engineer being told to come up with the vertebral column from scratch. After years, he might produce a primitive facsimile, only to hear the utterly mad suggestion: Okay, now lay a nerve cord of a million wires through the column, immune to injury from any movement. Everywhere the eye goes over the skeleton, there is a new composition: the voluting Ionic thigh, Corinthian capitals, Gothic buttresses, baroque portals. While high above, the skull roof arches like the cupola of a Renaissance cathedral, the repository of a brain that has taken all this frozen music to the bottom of the ocean, to the moon, and to a pro football field—the most antithetical place on earth for the aesthetic appreciation of 208 bones.

After nine years in the NFL, Joey Browner of the Vikings is a scholar of the terrain and a rapt listener to the skeleton, the latter being rather noisy right now and animated in his mind. It is Monday morning, and all over the land the bill is being presented to some large, tough men for playing so fearlessly with the equation of mass times velocity; only the backup quarterback bullets out of bed on recovery day. The rest will gimp, hobble, or crawl to the bathroom, where contusions are counted like scattered coins, and broken noses, ballooned with mucus and blood, feel like massive ice floes. Browner unpacks each leg from the bed as if they were rare glassware, then stands up. The feet and calves throb from the turf. The precious knees have no complaint. The thigh is still properly Ionic. The vertebral column whimpers for a moment. Not a bad Monday, he figures, until he tries to raise his right arm.

The bathroom mirror tells him it’s still of a piece. It’s partially numb, the hand is hard to close, and the upper arm feels as if it’s been set upon by the tiny teeth of small fish. Pain is a personal insult—and not good for business; he knows the politics of injury in the NFL. Annoyed, his mind caroms through the fog of plays from the day before, finally stops on a helmet, sunlit and scratched, a blur with a wicked angle that ripped into his upper arm like a piece of space junk in orbit. He rubs dipjajong—an Oriental balm—on the point of impact, dresses slowly, then slides into an expensive massage chair as he begins to decompress to a background tape of Chopin nocturnes, quieting and ruminative, perfect for firing off Zen bolts of self-healing concentration to his arm.

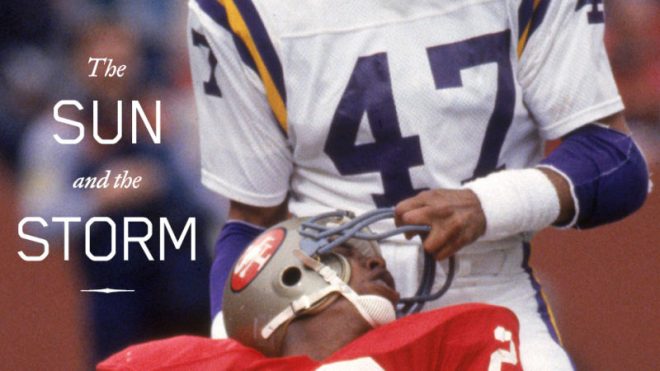

By the next morning, after re-creating his Monday damage probe, he appears more worried about his garden of collard greens and flower bed of perennials; given the shape of his arm, most of hypochondriacal America would now be envisioning amputation. That is what Browner would like to do, so eager is he to conceal the injury, so confident is he that he could play with one and a half arms. At six three, 230 pounds, he is a diligent smasher of cupolas, who has made more than one thousand tackles in his career. He is the first $1 million safety in NFL history; a six-time All-Pro; and a two-time conscriptee to the all-Madden team, an honor given out to those who have no aversion to dirt, blood, and freeway collision.

His only peer is Ronnie Lott, with whom he played at USC. Lott put the safety position on the map, invested it with identity, separated it from the slugging linebackers and the butterfly cornerbacks. It is the new glamour position in the NFL, due in part to CBS’s John Madden, a joyful and precise bone counter who always knows where the wreckage will lie. With schedule parity, the outlawing of the spear, the clothesline, and the chop block, with excessive holding, and so many tinkerings to increase scoring, pro football veered toward the static on TV. Madden, it’s clear, wanted to bring some good old whomp back to the game, and he found his men in players like Lott and Browner. Now the cameras are sensitive to the work of safeties, the blackjacks of the defensive secondary.

“If you want to find out if you can handle being hit by Ronnie Lott, here’s what you do. Grab a football, throw it in the air, and have your best friend belt you with a baseball bat. No shoulder pads. No helmet.”

Of all hitters, they have the best of it: time and space for fierce acceleration, usually brutal angles, and wide receivers who come to them like scraps of meat being tossed into a kennel. Lott delineates their predatory zest in his book, Total Impact, saying that during a hit, “my eyes close, roll back into my head … snot sprays out of my nostrils, covering my mouth and cheeks.” His ears ring, his brain goes blank, and he gasps for air. He goes on to broaden the picture: “If you want to find out if you can handle being hit by Ronnie Lott, here’s what you do. Grab a football, throw it in the air, and have your best friend belt you with a baseball bat. No shoulder pads. No helmet. Just you, your best friend, and the biggest Louisville Slugger you can find.”

Like medical students, pro players do not often dwell on the reality of the vivisection room, so Lott is an exception, a brilliant emoter with a legitimate portfolio, but still a man who has a lot of pages to fill with body parts and brute-man evocations. Browner has no marquee to live up to—except on the field. He is a star, though not easily accessible in media-tranquil Minnesota, distant from the hype apparatus on both coasts, part of a team that always seems to avoid the glory portioned to it annually in preseason forecasts.

Tuesdays are black days at a losing team’s quarters, soft on the body and miserable for the mind. It is the day when coaches slap cassettes of failure into machines, vanish, then emerge with performances graded, carefully selecting their scapegoats. Good humor is bankrupt. On this Tuesday, Viking coach Jerry Burns looks much like Livia in I, Claudius, who in so many words scorches her gladiators, saying: “There will be plenty of money for the living and a decent burial for the dead. But if you let me down again, I’ll break you, I’ll send the lot of you to the mines of New Media.” Browner smiles at the notion. “That’s it—pro football,” he says. “You don’t need me.”

“No tears like Lott?” he is asked.

“No tears,” he says. “I guess I don’t have much of a waterworks.”

“No snot?”

He laughs: “He must have some nose.”

“What’s total impact?”

“Like a train speeding up your spinal cord and coming out your ear. When it’s bad.”

“When it’s good?”

“When you’re the train. Going through ’em and then coming out and feeling like all their organs are hanging off the engine.”

“You need rage for that?”

“Oh, yeah,” he says. “The real kind. No chemicals.”

“Chemicals? Like amphetamines?”

“Well, I don’t know that,” he says, shifting in his chair. “Just let’s say that you can run into some abnormal folks out there. I keep an eye on the droolers.”

“Your rage, then?”

“From pure hitting,” he says. “Controlled by years of Zen study. I’m like the sun and storm, which moves through bamboo. Hollow on the inside, hard and bright on the outside. Dumb rage chains you up. But I got a lot of bad sky if I gotta go with a moment.”

“Ever make the perfect hit?”

“I’ve been looking for it for years.”

“What would it feel like?”

“It would feel like you’ve launched a wide receiver so far he’s splashed and blinkin’ like a number on the scoreboard. That’s what you’re after mostly.”

There is no dramaturgy with Browner, just a monotone voice, a somnolent gaze that seems uninterested in cheerful coexistence.

“Sounds terrible.”

“It’s the game,” he says, coolly. “If you can’t go to stud anymore, you’re gone.”

“I get the picture.”

“How can you?” he asks, with a tight grin. “You’d have to put on the gear for the real picture.”

There is no dramaturgy with Browner, just a monotone voice, a somnolent gaze that seems uninterested in cheerful coexistence. Or, perhaps, he is a model of stately calm. His natural bent is to listen. He does come close to the psychological sketch work of Dr. Arnold Mandell, a psychiatrist with the San Diego Chargers some years back who visited the dark corners of a football player’s mind. Now in Florida, Mandell says: “Take quarterbacks: two dominant types who succeed—the arrogant limit-testers and the hyperreligious with the calm of a believer. Wide receivers: quite interested in their own welfare; they strive for elegance, being pretty, the stuff of actors. Defensive backs: very smart, given to loneliness, alienation; they hate structure, destroy without conscience, especially safeties.”

Is that right? “I don’t know,” says Joey. “But it’s not good for business if you care for a second whether blood is bubbling out of a guy’s mouth.” Highlighted by cornices of high bone, his eyes are cold and pale, like those of a leopard, an animal whose biomechanics he has studied and will often watch in wildlife films before a game. An all-purpose predator with, a quick pounce, no wasted motion, the leopard can go up a tree for a monkey (“just like going up for a wide receiver”) or move out from behind a bush with a brutal rush of energy (“just what you need for those warthog running backs”). The mind tries for the image of him moving like a projectile, so massive and quick, hurling into muscle and bone. It eludes, and there are only aftermaths, unrelated to Browner. Kansas City quarterback Steve DeBerg served up the horrors in a reprise of hits he has taken: his elbow spurting blood so badly that his mother thought the hitter used a screwdriver; a shot to the throat that left him whispering and forced him to wear a voice box on his mask for the next six games; and this memorable encounter with Tampa Bay’s Lee Roy Selmon: “Lee Roy squared up on me. The first thing that hit the ground was the back of my head. I was blind in my left eye for more than a half hour—and I didn’t even know it. I went to the team doctor and he held up two fingers. I couldn’t see the left sides of the fingers—the side Selmon had come from. I sat on the bench for a quarter.”

Browner offers to bring you closer to the moment of impact. He puts some tape into the machine and turns off the lights. The figures up on the screen are black and white, flying about like bats in a silent, horrific dream. Suddenly, there is Christian Okoye, of the Chiefs, six one, 260 pounds, a frightful excrescence from the gene pool, rocketing into the secondary, with Joey meeting him point blank—and then wobbling off of him like a blown tire. “Boooom!” he says. “A head full of flies. For me. I learned. You don’t hit Okoye. He hits you. You have to put a meltdown on him. First the upper body, then slide to the waist, then down to the legs—and pray for the cavalry.” Another snapshot, a wide receiver climbing for the ball, with Browner firing toward him. “Whaaack!” he says. “There goes his helmet. There goes the ball. And his heart. Sometimes. You hope.” The receiver sprawls on the ground, his legs kicking. Browner looks down at him. Without taunting or joy, more like a man admiring a fresco. “I’m looking at his eyes dilating,” he says. “Just looking at the artwork. The trouble is, on the next play I could be the painting.” Can he see fear in receivers?

“You don’t see much in their eyes,” he says. “They’re con men, pickpockets.”

“Hits don’t bother them?”

“Sure, but you tell it in their aura. When you’re ready to strike, you’re impeding it, and you can tell if it’s weak, strong, or out there just to be out there.”

“So they do have fear?”

“Maybe for a play or two. You can’t count on it. They may be runnin’ a game on you. Just keep putting meat on meat until something gives. But a guy like Jerry Rice, he’ll keep comin’ at you, even if you’ve left him without a head on the last play.”

“The film seems eerie without sound.”

“That’s how it is out there. You don’t hear. You’re in another zone.”

“So why not pad helmets? That’s been suggested by some critics.”

“Are you kidding?” he says. “Sound sells in the living rooms. Puts backsides in BarcaLoungers for hours. The sound of violence, man. Without it, the NFL would be a Japanese tea ceremony.”

The sound, though, is just the aural rumor of conflict, much like the echo of considerable ram horn after a territorial sorting-out high up in the mountain rocks. NFL Films, the official conveyer of sensory tease, tries mightily to bottle the ingredient, catching the thwack of ricocheting helmets, the seismic crash of plastic pads, and every reaction to pain from gasp to groan. Network coverage has to settle for what enters the living room as a strangulated muffle. But in the end, the sound becomes commonplace, with the hardcore voyeur, rapidly inured in these times, wondering: What is it really like down there? It has the same dulling result as special effects in movies; more is never enough, and he knows there is more. Like Browner says: “Whatever a fan thinks he’s seeing or hearing has to be multiplied a hundred times—and they should imagine themselves in the middle of all this with an injury that would keep them home from work in real life for a couple of weeks.”

What they are not seeing, hearing—and feeling—is the hitting and acceleration of 250-pound packages: kinetic energy, result of the mass times speed equation. “Kinetic energy,” says Mandell, “is the force that dents cars on collision.” He recalls the first hit he ever saw on the sidelines with the Chargers. “My nervous system,” he says, “never really recovered until close to the end of the game. The running back was down on his back. His mouth was twitching. His eyes were closed. Our linebacker was down, too, holding his shoulder and whimpering quietly. I asked him at half time what the hit felt like. He said: ‘It felt warm all over.’” TV production, fortunately, can’t produce Mandell’s response. But there still remains the infant potential of virtual reality, the last technological stop for the transmission of visceral sensation. What a rich market there: the semireality of a nose tackle, chop-shopped like an old bus; the psychotic rush of a defensive end; the Cuisinarted quarterback; and most thrilling of all, the wide receiver in an entrechat, so high, so phosphorescent, suddenly erased like a single firefly in a dark wood.

Quite a relief, too, for play-by-play and color men, no longer having to match pallid language with picture and sound. Just a knowing line: “Well, we don’t have to tell you about that hit, you’re all rubbing your spleens out there, aren’t you, eh?” But for now, faced with such a deep vein of images, they try hard to support them with frenetic language that, on just one series of plays, can soar with flights of caroming analysis. War by other means? Iambic pentameter of human motion? The mysterioso of playbooks, equal to pro football as quark physics? For years they played with the edges of what’s going on below as if it might be joined with a 7-Eleven stickup or the national murder rate. It is Pete Gent’s suspicion (the ex-Cowboy and author of North Dallas Forty) that the NFL intruded heavily on descriptions of violence, as it has with the more killer-ape philosophies of certain coaches. If so, it is a censorship of nicety, an NFL public relations device to obscure its primary gravity-choreographed violence.

Admittedly, it is not easy to control a game that is inherently destructive to the body.

But claw and tooth are fast gaining in the language in the booth, as if the networks are saying, Well, for all these millions, why should we struggle for euphemism during a head sapping? Incapable of delicate evasion, John Madden was the pioneer. Ever since, the veld has grown louder in decibel and candid depiction. Thus, we now have Dan Dierdorf on Monday Night Football, part troll, part Enrico Fermi of line play and Mother Teresa during the interlude of injury (caring isn’t out—not yet). There’s Joe Theismann of ESPN—few better with physicality, especially with the root-canal work done on quarterbacks. Even the benignity of Frank Gifford seems on the verge of collapse. He blurted recently: “People have to understand today it’s a violent, vicious game.” All that remains to complete the push toward veracity is the addition of Mike Ditka to the corps. He said in a recent interview: “I love to see people hit people. Fair, square, within the rules of the game. If people don’t like it, they shouldn’t watch.”

Big Mike seems to be playing fast and loose with TV ratings—the grenade on the head of the pin. Or is he? He’s not all Homo erectus, he knows the show biz fastened heavily to the dreadful physics of the game. “Violence is what the NFL sells,” Jon Morris of the Bears, a fifteen-year veteran, once said. “They say they don’t, but they do.” The NFL hates the V-word; socially, it’s a hot button more than ever. Like drugs, violence carries with it the threat of reform from explainers who dog the content of movies and TV for sources as to why we are nearly the most violent society on earth. Pete Rozelle was quick to respond when John Underwood wrote a superb series in Sports Illustrated on NFL brutality a decade back. He condemned the series, calling it irresponsible, though some wits thought he did so only because Underwood explored the possibility of padding helmets.

Admittedly, it is not easy to control a game that is inherently destructive to the body. Tip the rules to the defense, and you have nothing more than gang war; move them too far toward the offense, and you have mostly conflict without resistance. Part of the NFL dilemma is in its struggle between illusion and reality; it wants to stir the blood without you really absorbing that it is blood. It also luxuriates in its image of the American war game, strives to be the perfect metaphor for Clausewitz’s ponderings about real war tactics (circa 1819, i.e., stint on blood and you lose). The warrior ethic is central to the game, and no coach or player can succeed without astute attention to the precise fashioning of a warrior mentality (loss of self), defined by Ernie Barnes, formerly of the Colts and Chargers, as “the aggressive nature that knows no safety zones.”

Whatever normal is, sustaining that degree of pure aggression for sixteen, seventeen Sundays each season (military officers will tell you it’s not attainable regularly in real combat) can’t be part of it. “It’s a war in every sense of the word,” wrote Jack Tatum of the Raiders in They Call Me Assassin. Tatum, maybe the preeminent hitter of all time, broke the neck of receiver Darryl Stingley, putting him in a wheelchair for life; by most opinions, it was a legal hit. He elaborated: “Those hours before a game are lonely and tough. I think about, even fear, what can happen.” If a merciless intimidator like Tatum could have fear about himself and others, it becomes plain that before each game players must find a room down a dark and distant hall not reachable by ordinary minds.

So how do they get there, free from fear for body and performance? “When I went to the Colts,” says Barnes, “and saw giant stars like Gino Marchetti and Big Daddy Lipscomb throwing up before a game, I knew this was serious shit, and I had to get where they were living in their heads.” Job security, more money, and artificial vendettas flamed by coaches and the press can help to a limited point. So can acute memory selection, the combing of the mind for enraging moments. With the Lions, Alex Karras took the memory of his father dying and leaving the family poor; the anger of his having to choose football over drama school because of money kept him sufficiently lethal. If there is no moment, one has to be imagined. “I had to think of stuff,” said Jean Fugett of the Cowboys. The guy opposite him had to become the man who “raped my mother.”

But for years, the most effective path to the room was the use of amphetamines. Hardly a book by an ex-player can be opened without finding talk about speed. Fran Tarkenton cites the use of “all sorts” of uppers, especially by defensive linemen seeking “the final plateau of endurance and competitive zeal.” Johnny Sample of the Jets said they ate them “like candy.” Tom Bass even wrote a poem about “the man” (speed), a crutch he depended on more than his playbook. Dave Meggysey observed that the “violent and brutal” player on television is merely “a synthetic product.” Bernie Parrish of the Browns outlined how he was up to fifteen five-milligram tablets before each game, “in the never-ending search for the magic elixir.” The NFL evaded reality, just as it would do with the proliferation of cocaine and steroids in the Eighties.

The authority on speed and pro football is Dr. Mandell, an internationally respected psychiatrist when he broke the silence. He joined the Chargers at the behest of owner Gene Klein and found a netherland of drugs, mainly speed. One player told him “the difference between a star and a superstar was a superdose.” Mandell tried to wean the players off speed and to circumvent the use of dangerous street product. He began by counseling and prescribing slowly diminishing doses, the way you handle most habits. When the NFL found out, it banned him from the Chargers. Mandell went public with his findings, telling of widespread drug use, of how he had proposed urine tests and was rebuffed. The NFL went after his license, he says, and the upshot was that after a fifteen-day hearing—with Dr. Jonas Salk as one of his character witnesses—he was put on five-year probation; he resigned his post at the University of California–San Diego, where he had helped set up the medical school.

“Large doses of amphetamines,” he says now, “induce pre-psychotic paranoid rage.”

“What’s that mean?” he is asked.

“The killer of presidents,” he says.

“How would this show up on the field?”

“One long temper tantrum,” he says. “Late hits, kicks to the body and head, overkill mauling of the quarterback.”

“How about before a game?”

“Aberrant behavior. When I first got up close in a dressing room, it was like being in another world. Lockers being torn apart. Players staring catatonically into mirrors. I was afraid to go to the center of the room for fear of bumping one of them.”

“Is speed still in use?”

“I don’t know,” he says. “I’d be surprised if it wasn’t, especially among older players who have seen and heard it all and find it hard to get it up. Speed opened the door for cocaine. After speed, cocaine mellows you down.” He pauses, says thoughtfully: “The game exacts a terrible toll on players.”

Joey Browner is asked: “At what age would you take your pension?”

“At forty-five,” he says.

“The earliest age, right?”

“Yeah.”

“Should the NFL fund a longevity study for players?”

“Certainly.”

“Are they interested in the well-being of players? Long term or short term?”

“Short term.”

“Any physical disabilities?”

“Can’t write a long time with my right hand. This finger here [forefinger] can’t go back. It goes numb.”

“How hard will the transition be from football?”

“I’ll miss the hitting,” he says.

“If someone told you that you might be losing ten to twenty years on your life, would you do it again?”

“Wouldn’t think twice. It’s a powerful thing in me.”

“They say an NFL player of seven years takes 130,000 full-speed hits. Sound right?”

“Easy. And I remember every one.”

Browner was answering modified questions put to 440 ex-players during a 1988 Los Angeles Times survey. Seventy-eight percent of the players said they had disabilities, 60 percent said the NFL was not interested in their well-being, and 78 percent wanted a longevity study. Browner was with the majority on each question. What jolted the most was that pro football players (66 percent of them) seem to be certain they are dying before their time, and that 55 percent would play again, regardless. The early death rate has long been a whisper, without scientific foundation. “We’re now trying to get to the bottom of this idea,” says Dr. Sherry Baron, who recently began a study for the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. “From the replies we get, a lot of players are nervous out there.”

“The owners will simply not recognize the degenerative nature of injuries.”

The Jobs Rated Almanac seemed to put the NFL player near the coal miner when it ranked 250 occupations for work environment. Judged on stress, outlook, physical demands, security, and income, the NFL player rose out of the bottom 10 only in income. With good reason. The life is awful if you care to look past the glory and the money; disability underwriters, when they don’t back off altogether, approach the pro as they would a career bridge jumper. Randy Burke (former Colt), age thirty-two when he replied to the Times survey, catches the life, commenting on concussions: “I can talk clearly, but ever since football my words get stuck together. I don’t know what to expect next.” And Pete Gent says: “I went to an orthopedic surgeon, and he told me I had the skeleton of a seventy-year-old man.”

Pro football players will do anything to keep taking the next step. As it is noted in Ecclesiastes, There is a season—one time, baby. To that end, they will balloon up or sharpen bodies to murderous specification (steroids), and few are the ones who will resist the Novocain and the long needles of muscle-freeing, tissue-rotting cortisone. Whatever it takes to keep the life. A recent report from Ball State University reveals the brevity and psychic pain: One out of three players leaves because of injury; 40 percent have financial difficulties, and one of three is divorced within six months; many remember the anxiety of career separation setting in within hours of knowing it was over.

What happens to so many of them? They land on the desk of Miki Yaras, the curator of “the horror shop” for the NFL Players Association. It is her job to battle for disability benefits from the pension fund, overseen by three reps from her side, three from the owners. For some bizarre reason, perhaps out of a deep imprinting of loyalty and team, players come to her thinking the game will be there for them when they leave it; it isn’t, and their resentment with coaches, team doctors, and ego-sick owners rises. Her war for benefits is often long and bitter, outlined against a blizzard of psychiatric and medical paperwork for and against. She has seen it all: from the young player, depressed and hypertensive, who tried to hurtle his wheelchair in front of a truck (the team doctor removed the wrong cartilage from his knee) to the forty-year-old who can’t bend over to play with his children, from the drinkers of battery acid to the ex-Cowboy found wandering on the desert.

“It’s very difficult to qualify,” Yaras says. “The owners will simply not recognize the degenerative nature of injuries. The plan is well overfunded. It could afford temporary relief to many more than it does. I even have a quadriplegic. The doctor for the owners wrote that ‘his brain is intact, and he can move his arm; someday he’ll be able to work.’ They think selling pencils out of an iron lung is an occupation.”

On Saturday, Joey Browner begins to feel the gathering sound of Sunday, bloody Sunday. He goes to his dojo for his work on iaido, an art of Japanese swordsmanship—not like karate, just exact, ceremonial patterns of cutting designed to put the mind out there on the dangerous edge of things. He can’t work the long katana now because, after thirty needles in his arm a couple of days before, it was found that he had nerve damage. So, wearing a robe, he merely extends the katana, his gaze fixed on the dancing beams of the blade, making you think of twinkling spinal lights. What does he see? The heads of clever, arrogant running backs? Who knows? He’s looking and he sees what he sees. And after a half hour you can almost catch in his eyes the rush of the leopard toward cover behind the bush where he can already view the whole terrible beauty of the game, just a pure expression of gunshot hits, all of it for the crowd that wants to feel its own alphaness, for the crowd that hears no screams other than its own, and isn’t it all so natural, he thinks, a connective to prehistoric hunting bands and as instinctually human as the impulse to go down and look at the bright, pounding sea.

This story appears in Football: Great Writing about the National Sport.