There were some hard miles on that bus, and harder ones on the man behind the wheel. His name was Oscar Charleston, which probably means nothing to you, as wrong as that is. He was managing the Philadelphia Stars then, trying to sustain the dignity of the Negro leagues in the late 1940s as black ballplayers left daily for the moneyed embrace of the white teams that had disdained them for so long. Part of his job was hard-nosing the kids who remained into playing the game right, and part of it was passing down the lore of the line drives he’d bashed, the catches he’d made, and the night he’d spent rattling the cell door in a Cuban jail. His players called him Charlie, and when it was his turn to drive the team’s red, white, and blue bus, it was like having Ty Cobb at the wheel. Of course the players never said so, because sportswriters and white folks were always calling him the black Ty Cobb and Charlie hated it.

While Cobb counted the millions he’d made on Coca-Cola stock, Charlie bounced around on cramped, stinking buses until he, like their engines, burned out. The Stars would play in Chicago on Sunday afternoon, then hightail it back to Philly so they could use Shibe Park on Monday, when the big leaguers were off. So they drove through the long night, with Charlie peering at the rain and lightning, wondering which was louder, the thunder or the racket his players were making.

When he could take no more, he glanced back at Wilmer Harris and Stanley Glenn, a pitcher and a catcher, earnest young men who always stayed close to him, eager to absorb whatever lessons he dispensed. “Watch this,” he said, yanking the lever that opened the bus door. Then he leaned as far as he could toward the cacophonous darkness, one hand barely on the wheel, and glowered the way only he could glower.

“Hey, you up there!” he shouted. “Quit making so damn much noise!”

The bus turned as quiet as a tomb. “I bet there wasn’t one player hardly breathing,” Glenn says. The Stars were a strait-laced bunch—“the Saints,” some called them with a sneer—and they weren’t inclined to test whatever higher power might be in charge. But Charlie was different from them, and everybody else for that matter. And when the thunder boomed louder still in response to his demand, he proclaimed his defiance with a laugh. If it didn’t kill him, it couldn’t stop him.

On my plaque they said I was versatile. They said I “hit well over .300 most years.” Most years. Like saying Joe Louis was a pretty good fighter. —OSCAR CHARLESTON in Cobb, a play by Lee Blessing

The words are the product of a writer’s imagination, but the inspiration for them was as real as the bile Charleston must have choked on every time his skin color was held against him, every time he was told he couldn’t play where he belonged. Bigotry handed him a one-way ticket to obscurity. Even when he went into the Hall of Fame, in 1976, he was overlooked. How could it have been otherwise when there were big names, white names—Bob Lemon, Robin Roberts—going in with him? Besides, the general public had been conditioned to think only of Satchel Paige and Josh Gibson, if it thought of Negro leaguers at all.

Satch and Josh had swept into Cooperstown after its walls of intolerance crumbled five years earlier, and a myth sprang up around them that made it impossible to imagine anyone having paved the way for them. But Oscar Charleston did. He played so long ago that even Double Duty Radcliffe, who was 103 when he died in 2005, said, “He was before my time.”

“If Oscar Charleston isn’t the greatest baseball player in the world, then I’m no judge of baseball talent.”

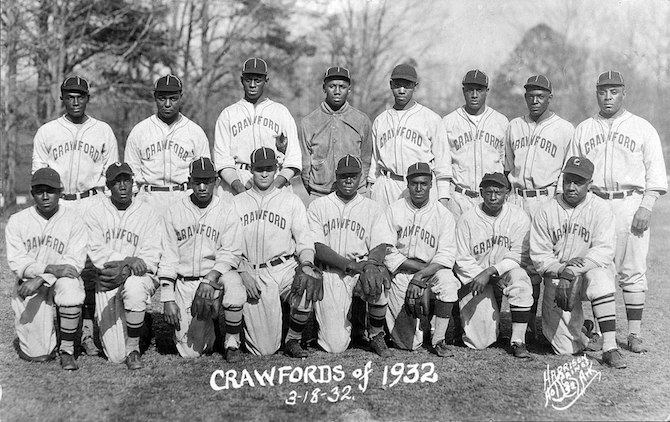

Double Duty exaggerated, of course, for the two of them were teammates on the 1932 Pittsburgh Crawfords. Yet by then Charleston had spent most of two decades as the reigning icon in black baseball. No matter what he did for the Grays—and he played first base, batted third, and managed what became the greatest Negro leagues team ever—there was always an old-timer around to say you should have seen him when he was really Oscar Charleston.

Starting in 1915 he turned centerfield into an art gallery on behalf of the Indianapolis ABCs, New York Lincoln Stars, Hilldale Daisies, and three kinds of Giants: Chicago American, St. Louis, and Harrisburg. His vagabond life was inspired by the disposable nature of the era’s contracts and the wisdom of another black baseball pioneer, Pop Lloyd, who said, famously: “Wherever the money was, I was.” At every stop, including Cuba in the winter, Charleston hung great catches as if they were paintings. He played shallow the way Tris Speaker did and Willie Mays would, but when he went back for a ball, legend says he performed acrobatics that have eluded everyone else in the position’s history, leaping, spinning, making catches behind his back. Yet his showmanship was founded on fundamentals that compensated for what was, at best, an ordinary throwing arm. Never would artistry interfere with winning.

And never, until Charleston moved on to the Homestead Grays in 1930 and declared himself too old and slow for the position, would a team of his put anyone else in center. Fellow centerfielder Cool Papa Bell, mesmerized by the sight of Charleston playing so close that he could almost shake hands with the second baseman, imitated the icon who became his manager on the Crawfords. And Gentleman Dave Malarcher, who patrolled the outfield with Charleston in Indianapolis, once said, “People asked me, ‘Why are you playing so close to the right field foul line?’ What they didn’t know was that Oscar played all three fields. I just made sure of the balls down the line, and all the foul ones too.” But when Charleston broke in with Indianapolis, he thought he was a pitcher. Maybe it was symptomatic of what Stanley Glen says, affectionately: “Oscar was left-handed, and he acted like a left-hander. You know, a little crazy.” Charleston was an Indianapolis kid, the seventh of eleven children born to an African American woman and a Sioux father who was a construction worker and, the story goes, a jockey. Oscar had enlisted in the Army at the end of the eighth grade, at age fifteen, and now, after four years and an infantry tour in the Philippines, he was playing for the team that once employed him as a batboy.

Maybe his days as a pitcher were done as soon as the ABCs saw him track a fly ball, just lower his head and not look up again until his internal radar had guided him to the spot where it came down. Or maybe the end came when the ABCs saw him booming baseballs to faraway places. It was a time when every team, black or white, was hunting for its own Babe Ruth, and here was another reformed southpaw pitcher who had the bat and the build: a hair under six feet tall, 190 pounds and getting bigger, with spindly legs and a chest-o’-drawers torso.

If, as historian James A. Riley suggests, Charleston never matched the Babe’s power, he was easily the black equivalent of Rogers Hornsby, who batted over .400 three times in one four-year stretch. Of course, he was faster than Hornsby and almost anyone else—the Army clocked him at 23 seconds in the 220-yard dash—and he was capable of dragging a bunt, stealing a base, and cutting the glove off your hand with his spikes if a throw happened to beat him. However you choose to look at Charleston, slugger or slasher, he raised enough hell with his bat to launch a thousand stories.

He hit the triple that gave the ABCs black baseball’s unofficial championship in 1916. He won, or tied for, five home run titles. In his best year, 1921, The Baseball Encyclopedia says he batted .434 with fourteen doubles, eleven triples, fifteen homers, and thirty-four stolen bases in sixty league games. That fall he had five homers in five games against a team of major league (i.e., white) barnstormers. Then he roared off to Cuba, where he batted .471. Even when he was calling himself an antique, he rang up a .372 average for the Crawfords in 1933, as if to remind the future Hall of Famers he was managing—Josh and Satch, Cool Papa and Judy Johnson—that he was made of the same stuff they were.

Teammates and opponents stampeded to proclaim his greatness. One of the few still standing, Buck O’Neil, the eternal flame of the Negro leagues, testifies that, as Double Duty Radcliffe put it, “a better player never drew breath.” Of the departed, Newt Allen, the Kansas City Monarchs’ second baseman, swore that Charleston hit the ball so hard, “he’d knock the glove off you.” Dizzy Dean, who faced him while barnstorming in the 1930s, described pitching to Charleston as a throw-it-and-duck proposition. Ted Page, a splendid Crawfords outfielder, told historian John B. Holway that Charleston introduced himself to the great Walter Johnson before an exhibition game by saying, “Mr. Johnson, I’ve done heard about your fast ball, and I’m gonna hit it out of here.” In Page’s account, which may qualify as legend become fact, a home run was indeed what Charleston hit. To win the game, naturally.

But all that is mere preamble to the proclamation that John McGraw issued from the game’s intellectual mountaintop: “If Oscar Charleston isn’t the greatest baseball player in the world, then I’m no judge of baseball talent.”

Decades later Bill James could hear the echo of McGraw’s endorsement as he set to work on his engaging, argumentative Historical Baseball Abstract. Swept up in the list-making orgy that defines contemporary culture, James wanted to rate the top hundred players ever. If he generated controversy by including a player who was a mystery to “a lot of very knowledgeable baseball fans,” he says, so much the better.

Numbers had to be crunched—James without statistics would be like Hendrix without his guitar—and other people’s lists had to be studied. But when it came to Negro leaguers, everything changed, because there weren’t always game stories and box scores to substantiate the players’ greatness. “When we went to New York, Chicago, Washington DC, they’d write up our games in the newspapers,” says ninety-three-year-old Andrew Porter, a victim of Charleston’s terrible swift bat when he pitched for the Baltimore Elite Giants. “But during the week we’d be out playing in small places, and you wouldn’t know nothing about it.”

So the list became for James a matter of the heart and the gut. “You wind up making a lot of assumptions,” he says. But at every turn, he found more praise for Charleston from men who had seen him play, men who knew his greatness to be the cold, hard truth. “There was a scout for the Cardinals, I think his name was Bohlen—he’d scouted for them for many years—and at the end of his career he said the three greatest players he’d ever seen were Cobb, Ruth, and Charleston,” James says. “He wasn’t hyping Charleston, he was just looking back, and he seemed so reasonable, so straightforward, that I said, ‘I’m willing to believe.’ ”

Thus did James anoint Charleston the fourth greatest player ever. Only the Babe, Honus Wagner, and Willie Mays are ahead of him, in that order. And—how Charlie would have loved this—Cobb is one place behind him. Then you have Mickey Mantle, Ted Williams, WalterJohnson, Josh Gibson, and Stan Musial. James expected at least one roaring good argument about Charleston’s presence in such august company. Instead, all he got was this: “stunned silence.”

Oscar Charleston deserves better.

Even when he was horsing around, you could sense the brute in him, the anger lurking just beneath the surface. It was there when he wrestled Gibson before games, supposedly for fun, two powerful men sweating and grunting and tossing each other around on the ball fields that both served and betrayed them.

Charleston was past his physical prime by this point, and he was giving away fifteen years to Josh, but damned if he’d let it show. “Must have been like two water buffaloes hooking up,” says Hall of Famer Monte Irvin, who heard all about it when he was a young Newark Eagle. A decade or more later, when Gibson was dead and Charlie was still full of the devil, he would playfully snatch up Stanley Glenn—“and I was six foot two and weighed 225 pounds,” Glenn says. The louder his young catcher squawked, the more Charlie laughed. It wasn’t always a pleasant sound. “You never knew when he was angry,” says Mahlon Duckett, the Philadelphia Stars’ second baseman throughout the forties. “They tell me in the old days, he could be laughing and knock you out.”

Charleston used his fists on everybody who crossed him regardless of pigmentation, on the field or off, as if breaking a nose or knocking out teeth gave him not just satisfaction but also sustenance.

Maybe that’s why the Crawfords’ Ted Page paid attention to Charleston’s eyes; he knew they wouldn’t deceive him. “Vicious eyes, steel-gray, like a cat,” Page said in Holway’s book Blackball Stars. To look into them was to see a man worth steering clear of in a fight, “a cold-blooded son of a gun.”

Charleston used his fists on everybody who crossed him regardless of pigmentation, on the field or off, as if breaking a nose or knocking out teeth gave him not just satisfaction but also sustenance. The smart ones backed down, the way professional wrestler Jim Londos, the Stone Cold Steve Austin of his day, did when Charleston threatened to throw him off a train for making too much noise. But at least one Ku Klux Klansman failed to get the message about discretion being the better part of valor, and, according to Cool Papa Bell, Charleston yanked the hood off his head and made him run like a scalded dog.

Laughing all the way, Charleston teed off on opponents, teammates, umpires, even the owner of the Hilldale Daisies. In all the accounts of Charleston’s battles, the closest thing to a recorded loss is when Oliver Marcelle, the Atlantic City Bacharach Giants’ hyper-violent third baseman, supposedly clubbed him over the head with a bat. That is one story, however, that Buck O’Neil is quick to shoot down in his autobiography, I Was Right on Time. “Oscar,” he says, “had a stoplight nailed to his chest.”

Still, Charleston was the fastest gun in the West, and challengers came from every direction, even the grandstand. One Saturday afternoon in Havana in 1924, Charleston was playing for the powerhouse Santa Clara team when he stole third base and carved up a Cuban infielder with one of his spikes-high slides. As the poor devil lay bleeding in the dirt like a Hemingway bullfighter, a uniformed Cuban soldier charged out of the stands and jumped Charleston from behind. Charleston shook off the cheap shot, then used the soldier for a punching bag until the cops showed up. They dragged Charleston off to the calabozo for the cell-door-rattling night he told his young Philadelphia Stars about a quarter century later.

“Jim Murray had a line about Frank Robinson and how he played the game the way the great ones played it, out of hate,” Bill James says. “I don’t know that Oscar was filled with hate, but there was a lot of anger in him.”

Charleston might have been scarred by the racism in his boyhood Indianapolis. “At that time,” says Riley, the historian, “there was more Klan activity in Indiana than there was in the South.” Something ugly might have happened in the Army too. But no anger-management specialist is needed to track down the most likely source of what drove him: Here was a proud man confronted daily by the fact that the world beyond the Negro leagues would never know just how great he was. He would never face Ty Cobb on the diamond, never find out once and for all if Cobb shouldn’t have been called the white Oscar Charleston.

The only reported instance of Cobb’s playing against blacks comes from the autumn of 1910, when he toured Cuba with the Detroit Tigers. He batted .370—he also got thrown out stealing by a Negro leagues catcher named Bruce Petway—and then he swore off interracial ball. So it took playwright Lee Blessing to conjure up a meeting between that snapping-turtle racist and Charleston, in Cobb. “Were you any good?” Cobb asks, as if word never reached him. “Better’n you,” Charleston replies.

It’s the only possible answer, for Charleston was locked in eternal competition with a legend who was his mirror image in everything except race and fame: played center field, batted left-handed, took no prisoners on the bases, even managed, and did it all furiously. Forever overlooked, Charleston had the right to be angry. But the Negro leaguers still with us hesitate to say so. And those who do say so are quickly negated by testimony that follows O’Neil’s benevolent template: “Charlie? No, Charlie wasn’t angry.”

Yet one afternoon in 2003, as O’Neil walked among the life-sized statues in Kansas City’s soulful Negro Leagues Baseball Museum, the awe he felt all those years ago returned to lower his guard. Double Duty Radcliffe, traveling by wheelchair, had joined him, and their eyes settled on Charleston’s defiant bronze presence.

“Look at that neck,” O’Neil said, and smiled appreciatively at what its thickness portended. “He’d knock you out the way.” And Duty said, “I seen him knock two fellas out in Indianapolis. Knocked ’em cold.”

They made the violence seem matter-of-fact, gave it the same ritual quality as a ballplayer’s knocking dirt from his spikes with a bat. But anger as ritual becomes something deeper, more profound. Better, perhaps, to call what drove Charleston an abiding rage.

The scrapbook’s yellowed pages are crumbling around the edges. The museum provides white cotton gloves for handling the book on those rare occasions that it comes out from under lock and key, but the gloves do only so much. The rest is left to fate, like the legacy of the man who kept the book.

Charleston gathered his clippings with little regard for their dates or the names of the newspapers they appeared in. His overriding interest, it seems, lay in stories that proclaimed him CHARLESTON THE GREAT in the States and EL FAMOSO PLAYER CHARLESTON in Cuba. But here and there are glimpses of something deeper than vanity. His obsession with Cobb surfaces repeatedly; one story wonders how much Charleston is worth if the Georgia Peach makes thirty thousand dollars a year. In an engagingly literate if disingenuous letter to the Pittsburgh Courier’s sports editor, Charleston writes about “[elevating] Negro Athletics to the place we would have them be” while claiming that umpires jobbed his Harrisburg team. And he takes special care to chronicle the way his brawl in Havana inspired cartoons, essays apologizing for the Cuban soldier’s “wicked attack,” and a public collection to buy him a gold watch (price: $82.50).

In the midst of all that, one clipping seems almost as if it came from somebody else: “Miss Jane B. Howard of Harrisburg, Pa., was quietly married to Oscar Charleston Thursday noon at the residence of Mr. and Mrs. Percy Richards, 3305 Lawton Ave.”

The story goes on to say that Charleston would be playing for St. Louis come spring, so the year must have been 1921. His wife was an elementary school teacher and the daughter of Harrisburg’s most prominent African Methodist minister, Martin Luther Blalock. She was well-read, knew much about culture and travel, and in time—she lived until a few weeks past her hundredth birthday in 1993—she became the Blalock family’s cornerstone. All of which makes her marriage to a divorced, brawling ballplayer three years her junior that much more puzzling. But Janie never did any explaining. “She was from an age,” says her niece Elizabeth Overton, “when you didn’t tell your business.”

It was no secret, however, that she had known tragedy before she met Charleston. Her first husband had died on their honeymoon, the victim of a flu that swept Cuba. “Our Janie was a widow,” Overton says. “Maybe that’s why she considered Charleston more than she would have.”

They made a striking couple, especially in photos in which they are dressed for winter, Oscar in a topcoat and fedora, Janie with a cloche pulled snug over her ears. She was pretty and petite, barely five feet tall but hardly shy. “She’d set anybody straight,” Overton says. One of the few secrets Janie shared was that she took Oscar to Sunday school, much to the amusement of his teammates. Not that they saw much of her. “She didn’t mix well,” Double Duty Radcliffe said. But she was with Charleston in Harrisburg for four seasons, and she accompanied him to Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, Cuba, and even a managing job in Toledo, until her father died in 1942 and she went home to care for her mother, home for good.

Janie never had children, and once she returned to Harrisburg, though she and Oscar didn’t divorce, there was no husband by her side. How much she saw of him thereafter is lost to time, but when he died of a heart attack in Philadelphia on October 5, 1954, nine days shy of fifty-eight, there was one last sign that he never stopped loving her: He willed her all his earthly possessions. And she turned right around and gave them to his sister, who had cared for him at the end.

It was an act of integrity, just as Oscar’s had been. To think anything else would be as wrong as to assume the worst because Janie never set out pictures of him. “You want pictures to last,” her niece says, “you keep them in the dark.”

Restless, always restless. At the plate he kept wagging that big bat until he found a pitch to demolish. Everywhere else he just kept moving. He worked security at Philadelphia’s Quartermaster Depot during World War II and ran the depot’s mixed-race ball club. He helped Branch Rickey seek out black talent for the Brooklyn Dodgers, and legend says it was Charleston who steered Roy Campanella their way. He tossed baggage for the Pennsylvania Railroad, and he umpired too. Unable or maybe plain unwilling to slow down, he signed up for a second season of managing the Indianapolis Clowns weeks before he died. When the guys who had played for him on the Philadelphia Stars went to his viewing in South Philly’s biggest hall, what they saw, Stanley Glenn says, was pure Charlie: “He looked like he was going to jump out of there and say hello to you.”

To this day, the last of the Stars can hear him barking at their best left-hander for throwing a “balloony pitch” and bitching at hitters who didn’t take every extra base in sight. They remember, too, a morning departure for a road trip when Charlie ordered whoever was driving the bus to pull out just as the left-hander ambled around the corner.

“But you said we were leaving at eight,” the players said. “It’s only five till.”

“Next time he’ll be early,” Charlie said.

There was only one way in Charlie’s world: his way. Time and again he let the Stars know it, but never so memorably as the night he picked up a bat to pinch-hit in an exhibition game. He was past fifty, and the lights in the park barely deserved the name, but he still bludgeoned a shot to right-center field. “It would have been [an inside-the-park] home run for anybody else,” Mahlon Duckett says. “Charlie fell out at third base.” And there the Stars assumed he would stay until somebody got a hit. But when the next batter flied to center, Charlie tagged up and broke for home, just the way he had in the old days. “I said, ‘What’s he doing?’ ” Duckett recalls.

He was doing what he always did when a throw beat him by ten feet. He was lowering his head and plowing into the catcher, and he wasn’t worrying that the catcher still had his mask on. Hell, Charlie probably relished it, even when his head hit the mask. The catcher dropped as if he’d been shot, and the ball skittered away, and the man who had risked his bull neck for a single run in a game that meant nothing left a message for all who would follow unaware: Tell them Oscar Charleston was here.

[Photo Credit: Harrison Studio, 1932 via Wikimedia Commons. Featured in the picture: Standing: Benny Jones, L.D. Livingston, Satchel Paige, Josh Gibson, Ray Williams, Walter Cannady, Cy Perkins, Oscar Charleston. Kneeling: Sam Streeter, Chester Williams, Harry Williams, Harry Kincannon, Henry Spearman, Jimmie Crutchfield, Bobby Williams, Ted “Double Duty” Radcliffe.]