It is a second-generation nickname. So many of them are these days. Young Glenn Rivers once wore a Julius Erving T-shirt to a basketball camp, for instance, and Rivers has been “Doc” all the way from Proviso East High School in Chicago to the Atlanta Hawks of the NBA. So, when Dwayne Alonzo Washington became a basketball star in Brooklyn by playing a herky-jerky style from the backcourt, he got his ungainly self called Pearl. After all, even in the late 1970’s, Earl Monroe’s bop still rang loud in New York ears.

Nicknames are the game’s informal heraldry, easily traced both forward and back. Very likely, there already are new X’s and Mailmen beginning their careers somewhere on the planet. In the other direction, you can trace the turns the game has taken, good and bad. There are the ones that never got out: the Goat, the ’Copter, the Fly.

Pearl idolized the Fly, a wild-style Brooklyn kid formally named James Williams. The Fly is half-dead twice-over now. He is half-dead from having been shot, and he is half-dead from living in a Bed-Stuy crackhouse where he survives on popsicles and curdled dreams.

It is the rare nickname that comes to a happy conclusion. It was a Brownsville player named Lloyd Free who brought World to the world, and Pearl idolized World, too. “That was the best part,” Washington says. “Just the competing. I loved to watch World B. Free when he played in Brooklyn. I loved to guard him. I wanted to see what he had. I wanted to see what I had.”

For a time, anyway, you could follow Pearl in either direction. You could follow him back through the game’s history and lore. It was said that Washington was playing for Boys High one night, and that he scored eight points in a row, and that he passed the opposing bench and told the other team’s coach, “Hey, yo. You better call a timeout.” It is wholly irrelevant that the incident is the purest moonshine. The point is, the same story is told in the Midwest concerning Oscar Robertson. That it was incorporated into Pearl’s legend so early on led you back through time to the Big O, and it seemed to lead forward past Pearl himself and toward future generations.

“I fulfilled my dream,” he insists. But he has not fulfilled his legend, which some people find far less forgivable.

By all practical measures, Pearl Washington has succeeded far beyond the vast majority of people who decide to make a living out of basketball. He was a star at Boys High and at Syracuse. He signed a big contract and he played in the NBA. He moved his family out of Brooklyn and onto Long Island. “I fulfilled my dream,” he insists. But he has not fulfilled his legend, which some people find far less forgivable. That became clear on the day that he lost his nickname—lost it for good among the only people to whom it truly had purchase, lost it among the people who play the game.

At Syracuse, people jived him about his chronic weight problem, and about his odd build. His shoulders slope at such a radical angle that they seem to begin at the base of his skull. He always has been bottom-heavy. He is so oddly cantilevered that, in full height, he projects an aspect somewhere between Groucho Marx and an albatross building up speed before takeoff. Some of his teammates in college laughingly called him “Olivehead.” When it mattered, though, when the game was on the line, he was still Pearl.

That changed one day in 1986. Darryl Dawkins looked over the New Jersey Nets’ rookie point guard at practice that day. Dawkins is a man of estimable good humor, whose wit is sharper than his competitive edge and infinitely more accurate than his jump shot. He looked at Dwayne Washington and he didn’t see a Pearl. He didn’t see Groucho or an albatross, either.

“Hey, Pearl,” Dawkins hollered. “Y’all floppin’ around out there, and you got no neck at all. You’re a seal, man.”

That was the beginning of the end for Pearl. He’d fall to the floor, and some Net would tell him, “Wipe the seal oil off those shoes.” If he showed up late for the bus, he’d be greeted by his teammates clapping their hands at arm’s length and barking uproariously.

It was not purely ridicule; it was not vicious enough for that, and Pearl took it with good grace. However, it was a way for the other players to tell Dwayne that he’d lost his rights to the nickname—and, indeed, a good portion of his identity—and that he had been disconnected form that continuum into which his early success had placed him. His personal coat of arms had fallen off the wall and shattered.

Beware any legend that has a B-side.

It was there that the slide began, the one that has taken Dwayne Washington from the top of his profession to the chilly armories of the Continental Basketball Association. His old nickname has been both mirror and yardstick. In it, he could watch the slide as it happened, and the world could measure the slide by the nickname’s heady standards. By 1986, Washington had been dispatched to the expansion Miami Heat. On one California road trip, a member of the Heat’s coaching staff suggested that head coach Ron Rothstein might take a look along the shoreline near some fish-processing plants. Every day, the canneries spread chum on the water and the seals came in to feast. Rothstein looked at the seals waddling along the rocks, thought about his point guard, and nearly fell laughing into the Pacific.

Dwayne Washington is a San Jose Jammer now, trying to get back to the NBA on $520 a week and $22 a day meal money. He seems also to be trying to come to grips again with who Pearl is, and what he was supposed to become. The lore now has his motel room awash in pizza boxes. He says that there is no more truth to that than there was to the story about the opposing coach and the timeout, but both of them have equal currency in the public mind. Beware any legend that has a B-side.

“I mean, what’s Pearl?” he asks, late on a cold night in Albany. “Who is the guy? Is he a guy who hits halfcourt shots? Is he the guy who goes between his legs, or is he a guy who makes that little play when the game is on the line? Is he a winner? I mean, Pearl, will you always be a winner?”

The Washington Street Armory here is a lifer. It was built in 1884 and thus has seen one war, two world wars, a police action, and a conflict. It is done up in government-red, government-green, government-gray, and the other grim colors with which the New Deal painted over the Great Depression. It smells sweetly of wood and old varnish. The visitors locker room contains 23 lockers, all of which are roughly the same shade of gray-green as the mildew in the sink. The room also contains the building’s fusebox, which looks worn and rather ominous.

The Albany Patroons have beaten the San Jose Jammers, 148-136, much to the delight of the Patroon advertisers who include Hot Dog Charlie’s (“Since 1922”) and the Miller Paint Decorating Center (“Since 1937”). Dwayne Washington has scored 22 points and handed out eight assists, and when he floundered into a near-fight with Albany guard Steve Shurina, it wasn’t Dwayne Washington that the fans heckled from the ratty old bleachers.

“Pearl, that’s an offensive foul anyway, you big dummy!”

Shurina and Washington are contemporaries. The former was a St. John’s substitute when the latter was a star at Syracuse. Consequently, they rarely played against each other.

“I remember Willie Glass,” Washington says later, “but who was that other guy from St. John’s?” That is where he is now, scrapping for another chance among the scrubs of his youth. He is 26 years old. He seems like the oldest man on the floor.

“It’s like you go from a position where everybody wants you to a place where nobody wants you,” he explains. “If it was somebody else, somebody with low esteem, maybe they don’t handle it as well. Maybe they pick up a gun. I don’t know.” Looking up, he sees the gray-green lockers, and the gray-green sink, and the tangled mess of a fusebox. Dwayne Washington shakes his head.

“I mean, it can’t get any lower than this, right?”

He was born on January 6, 1964, the youngest child of a laborer named George Washington. Shortly after Dwayne was born, the elder Washington’s knees went out, forcing him onto permanent disability. The nominal head of the family became the eldest son, George, JR., whom everybody called Beaver. Dwayne came to look at Beaver as a surrogate father. When Beaver played ball, so did Dwayne. As his younger brother’s skills blossomed, Beaver became his de facto agent. Thus began the marketing of Pearl Washington, 15 years after Dwayne was born.

It quickly became clear that the only was to get to Pearl was to go through Beaver. That was who the colleges contacted. “Beaver was very interested in Dwayne,” recalls Brendan Malone, an assistant with the Detroit Pistons who recruited Dwayne for Syracuse. “It was like dealing with Dwayne’s dad.”

His first year at Syracuse was a wonder and a delight. He hit a halfcourt shot to beat Boston College, and he ran off the floor before the ball touched nylon. He had a marvelous Big East tournament, personally burying Villanova and then, in the championship, scoring 36 points against Georgetown and chuckling as he did it. At one point, with the game at dagger’s length, he went to the line. Georgetown’s Freddie Brown stood three feet away from him, yapping in his ear. Washington looked over at the press table with a Do-You-Believe-This-Turkey? Grin on his face, hooked a thumb in Brown’s direction, and calmly sank the free throw. Madison Square Garden fell out entirely.

Truth be told, that season was the high point of his career. He played two more years at Syracuse, but they were vague and dissatisfying ones. There were never any more moments like that one against Georgetown. In 1986, he tried to go on the length of the floor against St. John’s to win the Big East championship and Walter Berry blocked his shot. By the time he declared he would enter the NBA draft early, many Syracuse fans were openly in favor of the move, preferring a young tyro named Sherman Douglas to Pearl, who seemed to them now to be old and in the way.

Few people knew that Washington had played his college career in considerable personal turmoil. He had fathered a child by his high school girlfriend, and his brother had fallen into bad trouble. Everyone in New York knew that Beaver earned his living in mysterious ways. “Look,” says one coach who became familiar with the situation “here’s a guy who was never at home, was always ‘at work’ and he worked out of his car. What does that tell you?”

On June 27, 1984, three months after Pearl had finished up his splendid freshman season at Syracuse, a man named Anthony Carter was beaten to death with a baseball bat on a street in Brooklyn. Police laid the blame for the killing to an internal dispute involving a drug-dealing gang called the Wild Bunch. Three men were arrested and charged with Carter’s murder. One of them was Beaver Washington, who was later released on bail.

The Nets selected Pearl as the 13thplayer picked for the 1986 draft. Agents trooped to Brooklyn to talk to Beaver about Pearl. The brothers chose a New York lawyer named Don Cronson, who negotiated a shoe contract for Pearl with the Avia company. Avia had wanted Len Bias but, as one of the last acts of his life, Bias had signed with Reebok. Avia still wanted a flashy East Coast name, however, and gave Washington a five-year deal worth $125,000 per year. They had bought the nickname as much as anything else. And after Bias was wheeled, dead, out of Washington Hall at the University of Maryland, it seemed Avia had gotten the better part of the deal.

That was the backdrop out of which Dwayne Washington came to camp with the Nets. His weight had ballooned from a barely tolerable 215 to a flatly grotesque 228. Dave Wohl, then the Nets coach, was completely at a loss. “We did everything,” Wohl says. “We yelled at him and we patted him on the butt. We fined him by the pound for being overweight, and we offered hum bonuses by the pound if he lost weight. Every button that you can push on a guy, we pushed on Dwayne.”

His game descended into sluggish mediocrity. His greatest gift always had been his ability to take smaller guards for rough rides into the lane, crushing them close to the basket. There never had been a need to develop a jump shot. Now, the guards were bigger and quicker, and, often, Pearl found himself caught in the lane with nowhere to go. He occasionally wound up rolling on the floor, looking mournfully at outbound transition. Thus did he come to he attention of Darryl Dawkins’ singular muse.

“In the beginning of the exhibition season, he was going up against kids that nobody had ever heard of, and they were just destroying Dwayne,” Wohl says. “He saw for the first time that he didn’t have that physical advantage any more.”

It began to be said that Washington was lazy, and that he was uncoachable. Wohl believes that to be too simple an explanation. “He really is a good guy,” Wohl says. “I really got on him and he never sulked, never talked back in anger, never tried to be disruptive. He was never the kind of guy you’d get rid of just because he’s a bad guy. It was never like that.”

“I hear a lot that I was so far ahead of my competition when I was in high school that I didn’t have to work, but that’s not true,” Washington says.

“I can’t have an opinion on why he is where he is,” says Sherman Douglas of the Miami Heat. “I just know that when I first saw him, he was the greatest point gaurd I ever saw.”

He was caught in a bad spiral. He was never in condition so he was always hurt, and because he was always hurt, he was never in condition. In 1986-87, he played only 72 games, and averaged 8.6 points. The following season, he played four fewer games and averaged 9.3. The Nets finally gave up on him, letting Miami take him in the 1988 expansion draft. Ironically, he was reunited there with Wohl, now an assistant coach with the Heat.

This may have been his last, great opportunity. The Heat were a mess, even by expansion standards. “Everything was lined up for him here,” says Wohl. “It was a club with no veterans, and he had his size and strength. We didn’t sign Rory Sparrow until the end of camp. All he needed was one good hard year here and he could’ve been set for life. He couldn’t do it. And if he couldn’t do it here, I don’t think he could do it anywhere.”

Again, Washington was injured. Again, he was overweight. He played only 54 games, averaging 7.6 points. He played one magnificent game against the Lakers in the Forum. That is what sticks in the minds of the people in Miami. That, and the bizarre hooley he found himself in with Armon Gilliam, then of the Phoenix Suns. The two fought on the court, and Gilliam charged after Washington in the Miami locker room. Washington had been on the way to the shower and he ran out of the locker room naked. “Get me a baseball bat!” Dwayne Washington screamed, bringing his plight into eerie symmetry with that of his brother.

It was shortly after this that Ron Rothstein looked at the seals and nearly guffawed away on the westerly tides. Washington was finished in Miami unless he brought himself to camp this season in the best shape of his life and made the team on his own. There was no chance of that.

“He found it extremely difficult to do it, night after night.” Wohl says. “He’s never pushed himself around the court. He’s always been overweight, and he’s never seen it as a problem. I’m convinced that, after three or four years of this, he just is what he is.”

Finally, last fall, the Heat cut him adrift. They were going to go with a younger, quicker point guard, a hungry kid who had lit up the summer leagues. A rookie named Sherman Douglas. “I can’t have an opinion on why he is where he is,” says Sherman Douglas of the Miami Heat. “I just know that when I first saw him, he was the greatest point guard I ever saw.”

“You know,” muses Dwayne Washington of the San Jose Jammers, smiling enigmatically, “Sherman never liked me. Never did at all.”

The oddest thing is that nearly everybody else does. Dave Wohl confesses affection for him, as does Eric Musselman, for whom Washington began his CBA career in Rapid City, South Dakota. “I’m not kidding,” says Musselman. “If there’s one guy I’d like to see make it back to the NBA, it’s Dwayne. When he first came in, I was really, really wary of the guy, of what kind of person he’d be. But, now, I don’t think he’d hurt a fly. He’s just a really nice guy.”

At first, he wasn’t going to go to the CBA at all. After failed tryouts in San Antonio and Milwaukee, Washington retreated to his Miami apartment. “For about a week, every day, I sat down for about a half-hour and just thought about should I go or not,” he says. “It was really hard. It was the first time in my life that I really thought about something like that. I just sat in my bedroom and thought about it.”

There were compelling reasons for him to play. If nothing else, his Avia contract was valid only as long as he played professional basketball, and it still had one more year to run. He could cost himself $125,000 by not playing at all. Later, he and Cronson would discover that Avia was reluctant to pay Dwayne Washington of the Continental Basketball Association. Avia paid for the Pearl, and they by God wanted the Pearl. The two parties are currently in litigation over the issue, but it shows how deeply the nickname could bite in both directions.

“What do come people want?” he says. “Do they want the Pearl? It’s so strange because, you know, here I am, in this situation, and people are still yelling ‘Pearl, do something great!’ That was more or less when I was younger.”

He went first to Rapid City, but he turned an ankle after six minutes of his first game, and he sat out long enough for the team to suspect him of malingering. He was traded for a third-round CBA draft pick—chump change, really—to the bottom, at least as far as basketball in the continental United States is concerned.

In a very curious way, he is back to being the Pearl again. The CBA is perilously short on a lot of things, including charisma. A player who was once a college star, and, before that, a New York City legend, is a rare commodity. Nobody in the CBA calls him a seal.

“I fulfilled my dream I played in the NBA. A lot of people never get close to that dream. My dream was to get to the NBA. I don’t know if people dream of being a star in the NBA. I don’t remember if I did.”

“Hey, we’ve even heard of the Pearl out there,” jokes Cory Russell, the 39-year-old Chuck Daily wannabe who coaches the Jammers. “He’s a star in college, and three years later, he’s a gentleman who desperately wants a fair chance. The people in San Jose just love him. I mean, hey, he’s the Pearl. They just take him for what he is right now. If it doesn’t work out for him, I think he’s at peace with that. He doesn’t carry any extra baggage. He’s just got a nice nickname, that’s all.”

He does what he’s told. He makes the plane on time. Nobody claps. Nobody barks. He carries the medical bag without having to be asked. He hangs with his teammates, as motley a crew as he’s ever played with. It includes people like Torgeir Bryn, the greatest Norwegian center in the history of Southwest Texas State.

Dwayne Washington’s personal life is still somewhat chaotic, although, on Jan. 31, after a trial lasting nearly a month, Beaver and his co-defendants—including the one who had delayed the trial because he was facing charges in three other murders—were acquitted of all charges in connection with the death of Anthony Carter. “They never had any evidence,” argues Dwayne. “So they delayed it as long as they could so they could go out and get some. My brother’s OK, though. He can handle it.”

He has fallen somewhat out of touch with his family. Moving three times in as many moths will do that. His car is in storage in Miami, and his life is largely in boxes there.

He insists that he is still trying to get back into the NBA. To that end, Russell has become the latest in a long line of coaches dedicated to the task of trying to get Dwayne Washington into shape. He has put him on a strict diet, something not easily done on the CBA’s Hold-The-Pickle-Hold-The-Lettuce per diem. Further, the Jammers play a hard, up-tempo style that forces Washington to run every second he is on the floor. He’s down to 215 again. It is widely believed that no NBA team will touch him until he is verifiably below 200 pounds. It’s been a long time.

“There’s always a risk in a guy like him,” admits Russell. “You think, ‘Why isn’t he in the NVA, and is there something I don’t know about him?’ I sense that that’s something of a burden for him. He’s OK about it, or as OK as a guy can be.”

“I’m going to give it all I can at this point right now, because if it doesn’t happen, there’s nothing I can do about it,” Dwayne Washington says. “The way I feel, when I was up there, I fulfilled my dream I played in the NBA. A lot of people never get close to that dream. My dream was to get to the NBA. I don’t know if people dream of being a star in the NBA. I don’t remember if I did.”

That would sound like simple rationalizing if it didn’t ring so true. It just might be that Washington’s failure as an NBA basketball player was not a failure of talent or a failure of nerve, but a simple failure of ambition. “When he says that all he wanted to do was get there, I think he may be telling the truth,” says Dave Wohl. “Maybe he just wanted to get there to prove that he could, but he wasn’t driven to stay there. If that was his goal, then he attained it.”

It is popularly supposed that Washington is now simply playing to collect on his show contract. There seems to be no great desire on the part of any NBA team to take another chance on him. Which may be where the nickname ends, too far along the heraldic line to be a Fly, but not far enough to be a World. A quirky sidelight. A minor character, interesting in his way. The Pearl, playing out of a dead man’s shoe contract in the gyms of last resort.

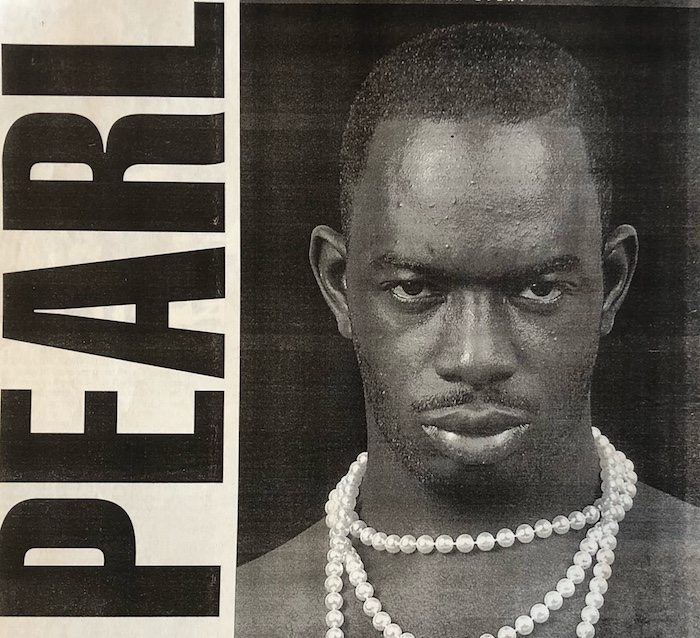

[Photo Credit: Bags]