They are slow this day at the baggage counter at the Seattle airport, and the players—up too early for the flight after a game the night before, anxious to get on with it, to get to the hotel so they can practice and then sleep—are waiting a little restlessly. An old lady and a young boy spot them. The boy is bashful, but the lady is not. She is quick and fearless, with a good first step for autographs. First Cowens. Then Bird. Then Tiny. Then she stops, looks around. Her eye picks up Pete Maravich—Pistol Pete. There is a quick vote in the chambers of her mind, and then she rejects him and moves on to M. L. Carr. Maravich is not unaware of this.

“It’s nice to be a star, isn’t it?” he says to Cowens.

Cowens nods.

“Touching, isn’t it?” says Maravich.

The Celtics are the Celtics again, the once and perhaps future champions, and they have the Rookie, and the excitement is palpable. The Celtics are special anyway, the only basketball team with a genuine tradition. They even look like their past, the uniforms curiously unfashionable, the green sneakers cut too high, the pants cut too long, making the players look heavy and dumpy—a touch of yesteryear. On the road the crowd comes early to the games, and the people—not just little kids and teenagers but grown men and women—throng around the Celtics basket, wanting to be near the Rookie, hoping to see, even in the warmup, something singular. The Rookie is aware of this, but he withholds his touch, even his look. He wills his eyes not to see them. He is comfortable within himself only as a basketball player, never as a showman, and so he is deliberately restrained. There will be nothing flamboyant in the warmup. It is as if he is determined not to gratify them, until the allotted 48 minutes of basketball. Then he will delight them, but only if it serves his game, and that of his teammates.

“Don’t give up on me,” says Maravich. “I’m coming around, I’m coming around. I know I am. I know I can do it.”

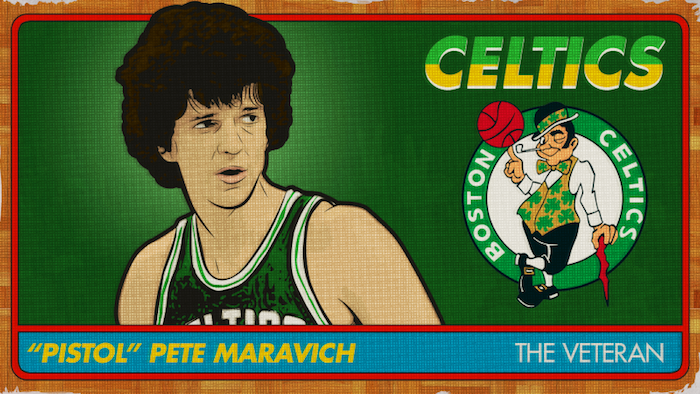

In the warmup drill, the Veteran who started the season as one of several players who made as much as the Rookie, until he was waived by the Utah Jazz, shows more panache. There is to even the simplest drill a style; nothing about him was ever ordinary, his signature was on everything he did, and though he was once the autograph, now the crowd barely sees him. It is looking for the Rookie, not the Veteran. There is a sense of instant replay about all this, for the Veteran was once the Rookie. People turned out for him, not his team, and they marveled at him and were often (regrettably) oblivious to the game and, more, to his teammates. Now all that is gone, and he is holding on by a thin thread. He is this night preparing for his fourth game with the Celtics, playing, in his own words, “like a donkey among thoroughbreds.”

Though he draws an estimated $180,000 a year from the Jazz, and reportedly will for 10 more years, he is the lowest-paid player on the Celtic team, “the only player on the team,” says coach Bill Fitch, “who makes less money than I do.” It is by no means clear that he can help the Celtics who want him in particular for the playoff games to come, who hope that some of the magic and touch remain. Nor is it sure that he will last the season. His pride, not his bank account, is at stake now. Ten seasons to go at $180,000 or not, he is in the twilight of his career, his knee in doubt, his speed questionable, his skills perhaps eroding. Above all, after a bitter early season in Salt Lake City when management engaged in a cold war with him, he is in terrible condition, unable to play at peak intensity for more than a few minutes at a time. Pete Maravich, who was once more powerful than his coaches everywhere he played, is vulnerable on this team—and he knows it. At practice early in the week on this road trip he does not play well. He is easily winded. Lesser players have blown by him. After practice Fitch comes over to him, shaking his head. Disapproval is thinly veiled, for Fitch is not a man to hide his feelings; it is his style to push his players, to zing them, to keep them just a little unsettled. “You’re disappointed in me, aren’t you?” Maravich says.

“Yes,” says Fitch, “I am. I can’t believe what kind of shape you’re in. I just don’t understand it.”

“Don’t give up on me,” says Maravich. “I’m coming around, I’m coming around. I know I am. I know I can do it.”

“I hope so,” says Fitch.

He had fallen on hard times, after his electric presence helped build the Omni in Atlanta and brought people to a football stadium in New Orleans. It was bad enough at New Orleans, a poorly run, struggling franchise, uncommonly stupid in its disposing of draft choices (not just too many high choices for him, but two firsts for an aging Gail Goodrich). Maravich was blamed for the team’s troubles as he had been before, with teammates openly criticizing him. But New Orleans was home, a city he loved. When the franchise failed, it moved this past year to Salt Lake City, and became the Utah Jazz. The Utah Jazz. Even the name is a contradiction, like naming a team, the Los Angeles Nordiques or the Seattle Suns.

The change of cities, as well as a change of coaches, had made his position different. Suddenly much of his leverage was gone. In New Orleans he was a local monument, in Salt Lake City an aging superstar. The coach was Tom Nissalke, not known for his love of superstars. And those who knew them both were not optimistic about their relationship and the clash of egos. The Jazz, with Maravich playing, had started badly. The record was 2–18, and Nissalke had decided that it was all over, that the team had to be rebuilt and the most basic way to start was to move Maravich. He decided to bench him completely. Maravich would not play for Utah, and the Jazz’s signals—to Maravich, to his lawyers and to other teams in the league—would have no ambivalence. As far as Nissalke was concerned, Maravich was dead. He became on official NBA stat sheets “Maravich-DNP,” as in Maravich-Did Not Play, the league’s version of a non-person. His confidence dropped. One day a Salt Lake City reporter asked what was wrong. Maravich took the reporter, placed him on the court as if he were a defender, and practiced going around him a few times. “See, I’ve still got my moves,” he said. Fans in other cities were underwhelmed by a Jazz lineup without Maravich. One night in San Diego, as Maravich sat on the bench in a wasted game, season-ticket holders seated across from the Jazz bench chanted: “Send the hostage in.”

What they remembered, of course, were not legendary games and rivalries, or playoff games, the Jazz against the Rockets, or the Jazz against the Celtics. They remembered the moves. All of them. None ever patented, because each move was an original, never seen before, never seen again. They were exciting, always so quick, as if Maravich himself did not know what he was doing until he had done it and then it was too late. Not just behind-the-back passes, and passes that were parts of acrobatic spinning reverses, passes, it was said, that were often too good for some of his teammates—but moves invented on the spot, moves that were ends unto themselves. Nothing in his repertoire was ever Xeroxed.

Everyone had his favorite Maravich Move Story. One writer remembers Maravich driving against a defender, the defender arms up, poised to block a shot, Maravich faking slightly, then flipping the ball above him and bouncing it off his head into the basket, as a driving seal might have done. Hot Rod Hundley remembers Maravich on a fastbreak with men on both wings, pushing the ball hard on the last dribble, flipping it in front of him with his right hand, as if to pass left, and then, with no break, suddenly slapping it with his right hand to the player on his right. When he was called for a travel, he yelled at the ref, “How can you call it a travel when you’ve never even seen it done before?”

If his moves seemed to take something away from the game, if they did not so much lead to anything as they simply dazzled, then on many occasions, given the Jazz, given the Hawks, they were better than the game. In those years, on those teams, when too little was really at stake, an original that excited was worth one that backfired. So his game was brilliant, but it was marked also by mistakes. When he joined the Celtics, the first thing Bill Fitch said was: “Pete, I’ve always had one problem with your game.”

“Yeah, I know,” said Maravich. “The turnovers.”

The worst thing that can happen to a basketball player in the NBA, Bill Walton has said, is to be the best player on a losing team.

It is no small irony that the consummate showman comes to the Celtics now, his skills waning, for his game has always tantalized purists. Red Auerbach always coveted him. “It took Red 10 years to get me,” Maravich says. Ten years ago, when Maravich—the highest scorer in college history—was averaging 45 points a game in his senior year, Auerbach said he was the best passer in the college game, perhaps the best in all basketball. Portland coach Jack Ramsay, the purist’s purist, has always been intrigued by Maravich because he knows the game and sees the court, the highest Ramsay accolade. But because his talents were never displayed in the right setting, the questions that hung over all his years in the pros remain unanswered: Was he flashy and showy because, in fact, that was the way he was? Or was he that way because he did not play with the great forwards and centers? Could he blend in? For not everyone who played with him was fond of Maravich—they often liked him personally, but they feared him amid the power he had, a power that reached into management, and they often felt that despite what he said about wanting to play a team game, the hardest thing for him to do was give up the ball.

Now Maravich arrives at the moment Bird ascends. A star is born; a star descends. Bird appears with such similar credentials that the comparisons are inevitable, a dazzling passer, a white fix for what some think is an endangered game. Boston loves Larry Bird; CBS loves him even more. It is a moment to reflect on the style and character and luck of both men, for the story of Pete Maravich, much of it poignant, so much of it unfulfilled, tells something about the game, expanded and promoted beyond acceptable limits; it also tells something about society’s materialism, and it illuminates, not just Maravich’s career, but Bird’s as well.

Bird, to outsiders, particularly in the media, is a troubling figure. He is good, very good with his teammates (and other basketball players), but he is reserved and suspicious, almost surly on intrusions from others—reporters, fans, hucksters. They are people outside his world, they invade his privacy and touch on the painful past, they mean trouble. They do not get his world right. But worst of all, every line that they write, every image that they project on a tube, separates him that much more from his teammates and thus the game. For all the hype, the talk of matchups, the Bird versus the Magic Man, see it on CBS (Magic loved the hype, loved the show biz; Bird hated it—forwards, after all, do not match up against guards), he plays remarkably pure, fundamental, indeed economic basketball. It is basketball made elegant by dint of such rare eyesight—Fitch calls him “Kodak” for the way he instantly photographs the court—great hands, intuitive intelligence, and moves so rare, at once practiced and spontaneous. He had signed a huge contract, $650,000 a year, so he is not just a basketball player, but a highly commercial one, and yet his true covenant is with his teammates and with the game. If the fans are his beneficiaries, all the better, but he is not there for their amusement. He is there to play basketball and to win. His skills must enhance the game, not the box office. So he is hyped and yet resistant to hype. His disdain for hoopla, which is seen by the press as the attitude of someone spoiled, may in fact be the reflection of someone as yet unspoiled; what seems about him corrupted may in fact be something quite uncorrupted. He is the rarest of contemporary athletic products, something better than advertised. He is also very lucky; he came to a franchise with the richest tradition of team play, a new owner, a new coach and a new Cowens, headed back toward winning anyway.

Maravich was never so lucky. He comes to the latter part of his career with his value as a basketball player still in question. The worst thing that can happen to a basketball player in the NBA, Bill Walton has said, is to be the best player on a losing team. Then the player will always be known around the league as a loser. Which is the story of Maravich, who now so desperately wants a ring.

From his college days on, there has been an irresistible temptation to take the brilliance of his game, and rather than discipline it, rather than make it fit a team concept, to exaggerate instead the already exaggerated qualities, to exploit not the gifts, the quickness, the eye, the skill of the hands, even the fearlessness, but the showmanship. Maravich was the creation, both victim and beneficiary, of modem sports married to modem media. In cities with dubious basketball constituencies, he was the show. Basketball was riot just a sport—the camera had helped change that—it was theater as well; there were arenas to be built, tickets to be sold, commercials to be filmed, products to be hyped, ratings to be boosted. He liked this but was smart enough to be aware of the dangers—that it was pulling him away from the most important thing, winning basketball. But given the legal structure of the league, the nature of the teams he played with, the temptation of the money he was offered, he was, in the end, unable to do anything about it.

In professional basketball at its best, a gifted and egocentric athlete gives up a share of his own game, and thus his own ego, perhaps 30 per cent of that which has set him apart from all the other talented young men, and he does this to make other players better. It is like asking a fine writer to give up, at the height of his career, a by-line. In Maravich’s case, what should have been sacrificed somehow was not. He was bent from what he should have been to what he became by the pressures of contemporary society. But he had nothing to be ashamed of; so, after all, were most of the league’s owners.

At LSU, a school with a weak program, he was the team. Worse, he was coached by his father, a man obsessed by Pete, in whose dreams Pete had come to live. (Press Maravich’s pro record: 1945–46, Youngstown, 31 games, 5.6 avg.; 1946–47, Pittsburgh, 51 games, 4.6 avg.) There were the scenes: Press coaching at North Carolina State, the game over, the fans gone home and Press’ little boy Pete coming out to practice for three and four hours, already showing those moves, dribbling two balls at once in circles, Press at LSU pushing his boy to shoot instead of pass. Press telling reporters, when Pete was compared to the legendary Bob Cousy, that Cousy never saw the day he had moves like Pete. For Press, consciously or unconsciously, gloried in Pete’s achievements and his reflected fame. A white flashy superstar, sure to be overpaid, would have enough trouble coming into the NBA. It would be even harder for Pete Maravich. He had spent three years playing for his father, a man who, on the court, had always indulged him. Where Press had gone, Pete had gone, and later where Pete went, Press went—father and son with identities too close for the good of either.

If LSU was not a healthy experience, then he was even less fortunate in the pros. In 1970, he was the third pick in the richest draft of a decade. Detroit picked first and took Bob Lanier; the old San Diego Rockets, picking second, took Rudy Tomjanovich. Atlanta (on a pick from the San Francisco Warriors) was third, Boston fourth. Atlanta was then a fine team— well-knit, well-balanced—of exceptional if not flashy players, remarkable role players: Bill Bridges as a power forward, Lou Hudson to play small forward or guard, Joe Caldwell as a defensive specialist, Walt Hazzard as one of the premier ballhandlers in the game. The Hawks were 48–34 the year before Maravich came aboard. They had played brilliantly in destroying Chicago in the playoffs before losing to Los Angeles. The players were very good and intelligent, and they were then paid roughly $30,000 to $40,000 a year. The fault with the franchise lay not with the players but the fans, who did not at that time accept a predominantly black starting team (at home one white player was often started over a black just to make the home folks feel a little better). Atlanta, which did not need a flashy guard on the court, needed a flashy white superstar for the gate. It chose Maravich. Boston then chose Cowens.

Even playing on a weak franchise, there were special days, matchups of sweet delight. He loved to play against Wilt Chamberlain, for if you were an inventive showman guard, Wilt was a wondrous challenge.

Maravich signed with the Hawks for $1.9 million for five years, one of the first big salaries. His arrival, the size of the contract, and the racial connotation therein tore that team apart. Caldwell demanded to be paid $1 more a year than Maravich, then jumped to the ABA. Within a year and a half, both Hazzard and Bridges were gone, and the team was no longer the same, no longer cohesive. Maravich was caught in the middle of something at once racial and commercial. Atlanta was not committed to winning basketball, but to a white superstar. His teammates, who had played for each other instead of the camera, were not amused. The record slipped to 36–46 each of his first two years. A fine piece of machinery was destroyed. It was a difficult time for him. He underwent constant stress, and there were varying illnesses, including a case of Bell’s palsy, a kind of facial paralysis. One day he found that his right eyelid simply would not close and the entire right side of his face was paralyzed. It was, his friends thought, almost surely an attack of nerves. It lasted 16 days, but it reflected some of the tension within.

Eventually, he was accepted by his teammates, first by Lou Hudson, a gracious and generous man. Later, he became close to Herm Gilliam, a black guard. The partial acceptance was important; he was, after all, a white player in a black world. The sport he played was becoming black, the ambiance of the locker room and the airplanes was black. Above all, the style he had created was derivative, not of whites but blacks. He was no scrappy-take-the-charge white guard. His game was in the mold of black artists, where the doing was as important as the done. He had studied Globetrotter films. It was, thought his friend Gilliam, as if Pete sometimes wished he were black, that it would all be easier and less schizophrenic then. Late at night, out with some black teammates, getting a little drunk on beer, it would show. (Getting drunk on beer amused the blacks. It was such a white thing to do.) When he was drinking, Maravich would often talk about how he wanted to be like them, but he knew they didn’t like him. Which was not true. In some ways they did like him, though the differences in salaries, in acclaim and in ink—plus the fact that the ball always seemed to be his—did not make it easy.

Even playing on a weak franchise, there were special days, matchups of sweet delight. He loved to play against Wilt Chamberlain, for if you were an inventive showman guard, Wilt was a wondrous challenge. Maravich liked to keep up a running dialogue:

“How high can you jump, Wilt?”

“Fourteen feet, boy.”

“Well, Wilt, my layup goes 14 feet, one inch and I’m going to dinner off you tonight.”

“You do, boy, and your head is going to be sore from the balls I bat down.”

On Maravich’s first drive that night, Wilt swatted the ball 16 rows into the seats. But Maravich adjusted, and soon the layups did seem to travel just one inch above Wilt’s outstretched hand. It was not in him, as he might easily have done, to shoot a little higher. It was important to taunt, as well as score. Then he and Gilliam developed an additional Wilt Teaser. They noticed that as they drove for layups, Wilt would key himself for the defensive move by crouching, timing his spring to their first movement of ascent. They decided they would fool Wilt; they would not, as a thousand coaches had taught, as nature itself demanded, jump to shoot, but instead would shoot quickly, while flat-footed on the court. It deprived Wilt of his alarm signal, and this enraged the big man. He would roar down the court after Maravich and Gilliam, “You little shits, I’m going to get you.”

There were finally some better days in Atlanta. Cotton Fitzsimmons arrived, a coach with an ego worthy of Maravich, perhaps the coach Pete should have had in college. A battle of nerves had ensued, and Fitzsimmons, Napoleon to some of the Hawks, had partially tamed Maravich. But Fitzsimmons’ arrival had signaled something else: Atlanta was about to become serious about basketball, and this was a team mired in the middle of the standings. The Hawks needed to trade, to get draft choices, and they had only two marketable players—Hudson and Maravich. Since New Orleans’ was just coming into the league, and since Maravich was a hometown boy, the temptation was irresistible. Maravich would go to New Orleans.

The Jazz wanted him so badly that they mortgaged their future—two 2 first-round draft choices, a second, other benefits. New Orleans wanted him because he could sell tickets; basketball had been born to many people there when he had arrived. As a college boy he had had his greatest moments in Louisiana. It was also the worst thing that could have happened to him. Bad enough starting with an expansion team, but the very price of the trade helped guarantee that the Jazz would remain weak; they were selling their souls, and his as well. All this ensured that he would remain the star with a marginal franchise, and it would be showmanship basketball again rather than creative but disciplined basketball.

He had often talked with his teammates, first at Atlanta and then New Orleans, about his future, about how desperately he wanted to be with a winner. As he played at New Orleans—brilliant, original, frustrated—his hunger grew. His second contract, for close to $400,000 a year, was up at the end of 1977. He often talked of playing out his contract and signing with one of the two teams that could afford him, New York or Los Angeles. Los Angeles had Kareem. Maravich often talked of playing with Kareem. Every great passing guard in the league dreamed of playing with Kareem, so much more appreciated by players than by fans. After this year’s all-star game, Kermit Washington of the Blazers came back to his team and told his teammates how Magic Johnson had always hung around Kareem, had never let him out of his sight, as if afraid of losing him; and Lionel Hollins, remembering the glory days in Portland with Walton, smiled and said, “Yes, if I had Kareem, I wouldn’t let him out of my sight either.”

Maravich talked with Gilliam about going to Los Angeles. But Gilliam, better schooled in the hardships of life, told him to forget it, the money at New Orleans would always be too great. No way you can get away. “My friend,” Gilliam had said, “they will not let you get away. You are the franchise.” Which was true, he was a prisoner of his skills and his showmanship. Other teams were interested, but the compensation would be so heavy, you had to destroy something. Was he really worth that much? So in 1977 he signed what was then a record-breaking contract—five years at $700,000 per—more even than Kareem was making. He thought about it a long time, but he decided in the end that he was not free, his value was so great that the compensation would be too high. He was a prince, not a movable serf. “To go anywhere good,” he said, “they have to give up too much. So they’re scared.” Then he added with a mild edge of bitterness, “You’re only free as your skills diminish.”

Both Boston and Philadelphia have impressive records, but they were, by midseason, considered suspect in their backcourts, not so much for day-to-day play—they both had enough to defeat most teams—but for the playoffs, when matchups become more important. (Seattle, for example, inhaled Washington’s backcourt in last year’s championship series.) Maravich was suddenly available. If he could come off the bench when the team was stalled and create that missing movement, then it would be worth signing him. He wanted to be with a winner, to get, in his word, a ring. And to shake the idea that he is a loser. That was a sensitive point. When he talked about his days with New Orleans, the statistics came quickly: “We were 93 and 92 when I was healthy, and when I was hurt, 15 and 46.”

Ask who knows the statistics in this league. The players know, that’s who.

The fixation with the ring, which was genuine, was not just a fixation with a championship and a desire for professional bauble, but an awareness of what his career has not been. “A stepchild of the American imagination,” former teammate Rich Kelley once called him.

He was relieved, he said, not to be the center of attention. The less exposure the better. There was, nonetheless, in the first few days at Boston, a fascination with him, even as he was trying to blend into his new, more anonymous incarnation; In those first few days, talking about the fuss made over him, he told John Schulian of The Chicago Sun-Times, “I wish I’d changed my name when I came here. I wish nobody knew me.” He was far more interested in gaining the respect of his new teammates. He was pleased one day when he had gotten on the team bus before a Portland game, wearing a skier’s knit hat, which had made him look ridiculous, thinner and more vulnerable, exaggerating, in particular, the nose. It lacked only an icicle hanging from it. He was not just a waif among athletes, but a cold waif, and they had teased him, “Petey! Petey!” And they were right. He did not look like a Pete, or a Pistol Pete, but a little lost Petey. He, knowing the effect, had clowned for them, flashing an idiot’s grin to go with the hat. A happy moment in his new home.

There were moments on the bench during the game when he would stare at Bird, a look that fixed Bird, as if he were trying to see inside another man. He was good about Bird. “The classic forward of the eighties,” he said, and one was reminded that 10 years ago when he had come in the league he had predicted that in a few years forwards and centers would have moves like his. And only then would he talk of how good and how rare it was to play with basketball players who had the exact same sense of the court that he did. The same ESP, in his phrase. When it happened, you did not have to explain, both of you just knew. There had been a couple of preseason games with Julius Erving, when the Doctor had briefly sampled the waters in Atlanta. Maravich remembered that they had divined each other’s moves. No one had suggested anything. “You didn’t have to say: ‘If they overplay, you go back door.’ ” It had been sheer pleasure. Fourteen assists. Or something like that.

He did not seek out interviews, but if reporters wanted to see him, he was agreeable; he was comfortable with this reporter. He did not complain about literary injustices inflicted upon him. He was gracious about it. Later he sought this reporter out, while the latter was eating lunch with Bob Ryan, a sportswriter for The Boston Globe. “Hey,” he said to the reporter. “You won a Pulitzer prize.”

“They wanted the best for you, Pete,” Ryan said. “They wanted Walter Lippmann, but they found out he was dead.” Maravich seemed pleased. It was as if the story would be better because the writer had the ring that Maravich coveted.

His talk always came back to the ring. If he had been with the Celtics for 10 years, he said, he would have two rings, maybe more. A reporter remembered what Gilliam had said: “He wants to play with a winner. Oh, does Pete want to play with a winner!” There remained a poignancy to him, the $700,000 underdog. It was as if everything had always gone a little wrong in his career—the wrong teams at the wrong times, Maybe the wrong teammates. In Seattle Hot Rod Hundley, noticing his newly frizzed hair, which somehow made him look even frailer, had asked about it; and Maravich had answered, ‘I couldn’t even get that right.”

The fixation with the ring, which was genuine, was not just a fixation with a championship and a desire for professional bauble, but an awareness of what his career has not been. “A stepchild of the American imagination,” former teammate Rich Kelley once called him. Not a bad summation for a 10-year career, which did fire the American imagination, sell tickets, sell soft drinks, sell sneakers—and somehow failed more than it succeeded. Nissalke may have had this in mind when he said, “We had such a hard time explaining to Pete and his people that he had almost no market value, that no one wanted him, or at least was willing to pick up the salary. You know, they just wouldn’t believe it.”

This is a closely knit team and there is a fear among the players that one of the lesser players, Eric Fernsten or Jeff Judkins, will be cut for Maravich. Fitch does not want to add Maravich at the price of team unity. If Maravich works out, Fitch intends to rotate Don Chaney, Fernsten, Judkins and Maravich on and off the five-game injured reserve list. The real question is: Can he help?

In one early game against Detroit, he carne in and gave the Celtics an immediate boost. Now the Celtics are on a key Western trip of five games; the most important is a nationally televised game against Seattle. Against Phoenix—a sound team with a strong backcourt, Paul Westphal and Don Buse—Maravich plays in the second quarter. His frizzed hair makes him look all the more like a street urchin who has wandered in to play with the big boys. He seems slow and tentative on the court. It is not a good night for Boston, which blows a nine-point lead in the final two minutes. At the end, Maravich is not playing.

Two nights later in Portland, against a struggling team, Maravich comes in for 13 minutes, but is more awkward than against Phoenix. He is open for shots and then hesitates before passing the ball off. On the sideline, Fitch, frustrated, is yelling, “Pete! Pete! Be decisive! Be decisive!” Pete Maravich, son of Press Maravich, is being told in his 31st year on this planet to be decisive.

It does not bode well. No one is quite sure what the problem is—his bad knee, his bad condition, his uncertainty about his role. There have always been defensive flaws in the past, but with Cowens behind him, perhaps Boston can afford the flaws for the trade-off on offense. But is the gap too wide? Is it too late to get in shape?

Boston enters Seattle for the biggest game of the trip. The night before this game, Fitch, a film nut, watches the replay of Dennis Johnson’s last-second three-pointer that led to Seattle’s double-overtime win over Boston in their last meeting. As he sees DJ hit, he curses the Boston timekeeper. “It would never have happened in Madison Square Garden,” he says. “They have a great timer there.”

The fixation with the ring, which was genuine, was not just a fixation with a championship and a desire for professional bauble, but an awareness of what his career has not been.

It is a marvelous game, a promise of playoff games to come. For Boston, the toughest matchup is in the backcourt. Seattle, with Johnson, Gus Williams and Fred Brown, has the best backcourt in the league. In the first quarter, DJ and Williams share 27 of Seattle’s 33 points. It becomes clear Maravich will not play today. Fitch shifts M. L. Carr to guard, and plays an injured Gerald Henderson instead of Maravich. Seattle is simply too quick and too strong, the game too important and too close for him to play. Boston leads 108–103 with two minutes left, but blows it, 109–108.

It is a bad omen for Maravich. If he is to be of value, it must be in games like this. After the game, the reporters gather for the tribal rituals, surrounding Fitch, M. L. Carr and Bird. Maravich is off to the side, dressing by himself. I am talking with him, and we are joined by Rich O’Connor, a basketball player turned writer. O’Connor has always been fascinated by Maravich. They talk about the game, and O’Connor asks Maravich how he feels about the Celtics. Maravich says he loves it, the idea that everything is for the team, for the Celtics. It is a wonderful atmosphere, he says, free of the burden of statistics.

“I hate statistics,” says O’Connor. “I think they should never keep them. They ruin the game.”

“No,” says Maravich. “No, what they should do is give you your opponent’s stats. That and nothing more. What your guy did against you.”

And with that he dressed slowly and made his way to the bus, untouched by the crowd.

[Feature Image: Sam Woolley/FMG]