Electric sound rushes out of the Gray Manse in Lake Mahopac, New York, splitting the still, winter air. On weeknights, carloads of teenagers from sleepy towns in upstate Putnam County follow the road around the lake and park in the driveway, drinking beer and listening. Some of them get up the nerve to walk past the marble columns into the three-story mansion, and come bolting out, laughing and squealing details of the strange world inside.

The Gray Manse, once the summer estate of a marine welding executive, is home, rehearsal hall, and recreation center for Rhinoceros, a year-old rock group that consists of seven musicians, two equipment managers, a road manager, a rotating pool of young women, and a friend called Lan, a young man who makes clothes, cuts hair, and cooks. Two of the band members are rehearsing in the basement. The rest of the house, at five in the evening, is waking up and having breakfast. John Finley, a short, toothy figure with coarse blond hair that makes two or three waves before dropping to his shoulders, rides down the grand staircase in a moving chair. The rooms on the bottom floor are high-ceilinged, lavish period settings from the nineteenth century, like an antique suite at the Metropolitan Museum with all the velvet ropes down. John, in sky-blue pants and a purple and blue poncho, is swallowed up by the colors and textures: blue oriental carpets, gold-encrusted statues, stuffed elk, Victorian furniture, and candelabra.

On the upper floors, the rock group has been able to impose its own milieu—candles, frankincense, psychedelic posters, and Indian silks thrown over the fluted lampshades. There are stereo and television sets in every room, all playing at top volume. In the front bedroom, Alan Gerber, twenty-one, is lying on a pink silk spread listening to Thelonious Monk.

When John comes upstairs with a bowl of cereal and milk, he puts on a gospel record, Run, Sinner, Run, by the Davis Sisters. “Nothing moves me as much as gospel music,” he says.

Across the hall, Danny and Steve Weis, brothers, are watching Land of the Giants on television and listening to Judy Collins on the stereo. Danny, twenty, is the pivotal sexual force of the group. He is tall and haughty, with ice-blue eyes, a pouting mouth, and a head of long, flaxen hair that is layered, teased, permanent-waved, ratted, and sprayed until it has acquired the consistency of cat’s fur. Steve, seventeen, is dark-haired and so thin—110 pounds on a six-foot, one-inch frame—that when he stands on stage in skin-tight black pants, he looks like a Vogue model photographed with a distorting lens.

A blast of organ sound rises from the basement, drowning out all the records and television sets. Michael Fonfara has turned his amplifier all the way up and is jamming on the keyboard in the high register. Danny says to his brother, “Let’s go down and join him.” Billy Mundi and Doug Hastings, who are married and don’t live in the main house, have arrived, and the band is soon assembled.

Danny, on lead guitar, rips into a new song and moves around the room, pulling after him the red umbilical cord that ties him to the amplifier. He stands in front of Doug, and they stare into each other’s eyes, moving and nodding in unison until—sync—they are playing in sync, not looking at each other’s hands on the guitars, only the eyes. Danny turns to his brother, Steve, on bass guitar, pulling him into the rhythm—sync. Then he walks to Billy on the drums, catching his eyes and matching up with him. Then Michael on organ, Alan on piano, John singing at the microphone, until everyone in the room is pitching the same way, nodding at each other, and the air is steaming with this communion.

At this moment, which the musicians call “magic” or “holy,” they experience intimations of transcendence of self. Alan describes it: “When we’re really getting it together, playing, we’re all at peace together. You’re not even you anymore. You don’t have to contend with the hangups that Alan has. All of a sudden, you’re part of something that seven people are feeling. The music is crashing all around you, but you’re at peace, in the center of it.” Beyond the ear-bruising electric pounding is a state where, John says, “You cease to be. You’re just a vessel, the instrument of your soul. The music is playing you.” The group works for that transcendence every time they play. They reach it for moments, during certain songs, but the complete experience is rare. “When we play a set that has it throughout, everybody walks off like this.” John folds his hands in prayer. “It makes us happier than anything in life.”

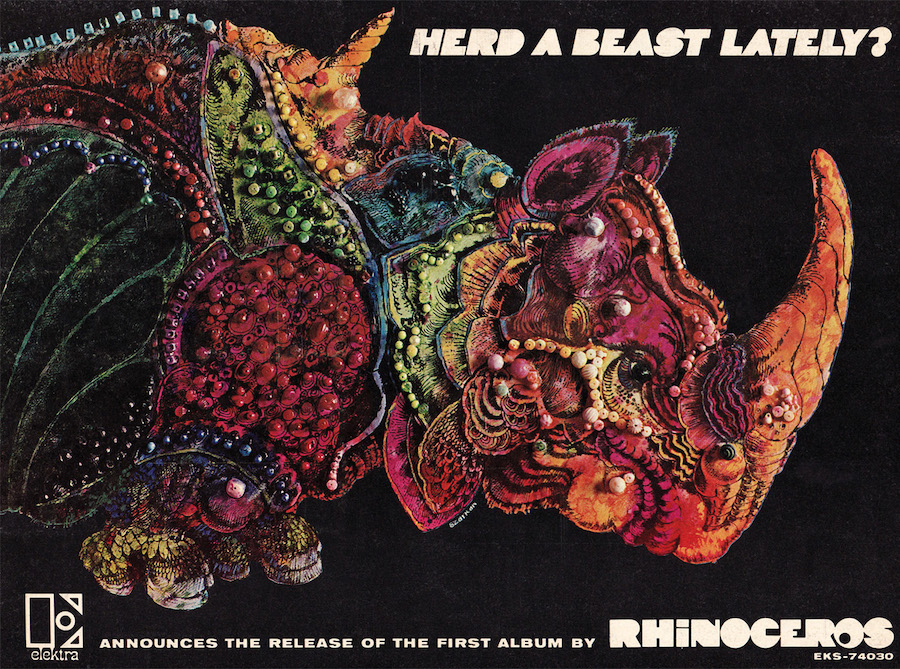

Rhinoceros, a coalition of rock veterans who have served their time in different bands, is past the scuffling stage that young rock groups go through—playing at college dances, auditioning on off-nights at coffee houses, dragging demonstration tapes from record company to record company. With an album out on Elektra and a single, Apricot Brandy, which is 47 on the national charts with a red bullet meaning WATCH-IT, Rhinoceros is able to demand enough money for performances to keep the ten-man entourage living high in Mahopac. They rehearse during the week, travel and play on weekends, and, if popularity grows, will make a new album every eight to nine months.

It is the hair, of course. The hair brands them—outsider, alien.

When the band rehearses until the early hours of the morning, the current groupies, who go by exotic names like Pandora, Nico, and Honey, have the run of the Gray Manse. They gather on the second-floor landing, trade scarves, blouses, hair rollers, and fish stories about the rock stars they have slept with. The groupies are part of a network of girls across the country who make a life of pursuing rock musicians. They live together, work on and off in discotheques and clubs, clothing stores and record companies, leaving the job for any musician who will take them home for a few days.

Honey claims to be the ex-girlfriend of Jimi Hendrix—the supreme phallic symbol of hard rock. She is telling the other girls, “Jim Morrison wants me to come live with him, and Mick Jagger is sending me a ticket to London….” Pandora, a rougey blonde wearing a feather and sequin costume, has just been hired as a Playboy bunny. Smiling, empty-eyed, she says, “They want me for centerfold.”

The groupies dress each other up in see-through blouses, golden chains, and furs, and descend the stairs to the basement. No one in the band acknowledges their entrance. They leave after a half-hour and take a two-hour communal bath. Like a mini-harem, the girls amuse each other and stay apart from the band, until it’s time to go to sleep. They raid the downstairs kitchen, find nothing but Wonder bread, cereal, giant jars of peanut butter and jelly, and king-size cartons of milk. Once in a while, someone in the house will make soup or a stew, but the normal daily diet is cereal and sandwiches. The girls settle for Puffed Rice with powdered sugar, and decide to explore the glassed-in sun porch of the mansion. Among the wicker and chintz furniture is an old Victrola with a cabinet full of 78 records. Honey takes one out, cranks up the machine, and places the heavy, cylindrical needle down. As the pounding of Rhinoceros rattles all the glass, George M. Cohan begins to sing in a scratchy, distant voice: “My girl May, she meets me every day, in fact we used to go to school together….”

One of Howard Johnson’s orange and blue installations comes into focus on the New Jersey Turnpike, halfway between New York and Philadelphia. Four of the Rhinoceros trek across the parking lot in their blazing colored silks, leathers, fringes, tassels, and flying hair. They are greeted by whistles and catcalls from a group of truck drivers. Alan turns to John, who is wearing a neon-orange T-shirt and suede vest, his blond curls bouncing and his eyes puffed up and pink from sleep. “You look like a depraved chick.”

The band drives in two rented cars, collecting receipts at every tollbooth, gas station, and highway eatery. Danny Hannagan and Burt Schraeder, the equipment men, drive the instruments and amplifiers, together worth more than $10,000, in a rented Avis truck with giant Rhino posters on the sides. When they fly, they call a special airline service that packs the equipment and hustles it through terminals. Hopefully, the baggage, Danny, and Burt arrive at the concert hall several hours ahead of the group, so that when the band walks in, everything is set up to play.

In Philadelphia, the first car stops at a gas station for directions. Doug rolls down the window to talk to the attendants in the glassed office, but before he can open his mouth, one of the mechanics yells, “Naaaaaa,” and gives them the finger with his grease-blackened hand. “Naaaaa, dirty punks, naaaaaa.”

Every time it happens, the group is taken by surprise. “What’s with that guy? Jee-sus. I wish we had a long stick with a boxing glove at the end of it, so we could just let him have it.”

It is the hair, of course. The hair brands them—outsider, alien. There are two attitudes people take toward the band. One is a castrating, motherly kind of amusement: “Boys will be boys, aren’t they cute in their little costumes.” The chef at the Mahopac Diner where the band often eats keeps their picture on the counter, feeds them and clucks over their bony frames. The other attitude is more common: “Naaaaaa, ya dirty punk.” John Finley was once waiting to pay the cashier in a Boston restaurant when a florid-faced Irishman turned on him: “You’re obnoxious, you creep. Braahhh!” Never, except in hippie districts of big cities, do people look at the band members simply as other people. Rock musicians have built this moat between themselves and the rest of the world with a stylized look—shoulder-length hair is the chief ingredient—that represents a deeper, inner separation.

Playing rock is a means of living out a definition of the good life that defies the American dream: never have a steady job, keep crazy hours, get stoned, play music, draw constant attention, and, if you do all these things well, make lots of money. The band members look at ads in the magazines—see the gray-haired couple in the rowboat, the happy wife is handing her happy husband a worm for his fishing rod. If you squirrel away now for the future, you can retire at sixty and have a cottage on a lake. The reasoning behind this scene—years of working, saving, putting off, sacrificing—has no meaning to rock musicians, and to an increasing number of young people who listen with puzzlement to job recruiters on the campus, talking of pensions and sick pay and medical benefits. They know people their own age who have bypassed the corporation jobs and are living at the rainbow’s end of the work ethic—the mansion on Lake Mahopac. If young people can live in Big Sur, or Florida, or the Catskills, without saving for forty years at the Dime Savings Bank, what does this mean to people who have gone the other way, postponed their desires, worked at dehumanizing jobs? It means, to some of them, that maybe what they did was all unnecessary. Is it surprising that the man in Boston is moved to rage when he sees John Finley with his long curls and wallet full of money?

None of the Rhinos, who range from seventeen to twenty-six, has ever had a regular job, nine to five, or even a part-time job. With the exception of Billy, who is an ex-Hell’s Angel from East Los Angeles, they all come from middle-class families. Their fathers are insurance salesmen, engineers, shoe retailers, who made sure their sons didn’t starve until they were making their living through rock. Billy was out on his own at eighteen. “It was either music or a white-collar job,” Billy thought. So he started playing rock and studying music at UCLA.

Each Tuesday, the band members get $70 in cash. Their manager pays the rent on the house in Mahopac, which is $400 a month in the winter but jumps to $1,700 a month in the summer. The manager also pays for car rentals, musical equipment and maintenance, and expenses on the road. As the band’s album, Rhinoceros, climbs up the charts, they can demand higher prices for live performances. But it is difficult for the album to catch on until the band moves around the country, stirring up interest. The two feed each other.

In the early stages, they are lucky to break even. If they earn $1,000 a night, the manager and booking agent each take 15 percent off the top. After hotels, meals, and transportation costs, there is perhaps $100 to be split seven ways. Rhinoceros is beginning to command $2,000 to $3,000 a night. Blood, Sweat and Tears, whose album was number one in the country, could ask $7,000 to $10,000. Supergroups like the Doors can earn $50,000 including a percentage of the gate.

Inside the Rhino car, Philadelphia looks gray. The people on the streets seem bloodless. They look inside the Rhino car and their eyes pop, they do double-takes. At the Franklin Motor Inn, the boys pair off, two to a room. The television sets snap on instantly and stay on until the band checks out. Michael and Danny set up colored candles and start incense burning on charcoal.

At 8:00 P.M., after eating steaks and shrimp, both the consistency of rubber, in the motel restaurant, they drive to the Electric Factory. The place is a psychedelic barn with a circus theme—swings, slides, funny-house mirrors, Dayglo-painted benches, and a hot-dog stand. In the dressing room, John starts to write the set, deciding what numbers to play in what order. Everyone except John and Doug, who meditates for a half hour before playing, is stoned, pacing, anxious to get on stage. They file out past benches of teenager’s in shetland sweaters and respectable haircuts, tune up, and are on.

Danny’s costume is a long, Western-style black leather jacket and a black bowler hat. With his pale skin and yellow-white hair sticking out in points from under the hat, he looks like a spook—one of those skeletons in top hat and tails that dance through children’s cartoons. Danny bends at the knees, straight-backed, and starts the band into Apricot Brandy.

“I learned from being married that you have to get all the sex thing out of your system, because the music is so tied up with sex that it’s a real struggle, even if you’re married, not to go after it.”

The sound of Rhinoceros is hard white rhythm ’n’ blues, with country, funk, and gospel influence. When the group first made recordings, John says, “We listened to the tapes and they sounded just like a rhinoceros. The bass and drums sounded lumbering and fat.” He hits his fists on his knees. “Choonka, choonka, choonka! Like a big animal going through the mud.” Rhinoceros never plays a song the same way twice; the performance varies with the group’s emotions. On stage, Danny moves around to each player, yelling, “Oh yeah, go!” Alan pitches forward over the piano, and when he sings, his soft features pinch up around his aquiline nose, giving him the pained, sour look of an ascetic Jew. Doug, with his happy face and ringlets of brown hair, arches his body against the guitar. Michael plays the organ half-standing against a high stool. He wears pink goggles and an Indian mirror cloth shirt unbuttoned to show his olive skin. John directs the show, talking to the audience, banging on a cowbell.

John is soaking when he comes off stage. He pulls off his shirt, and a blonde wearing a tweed skirt that barely covers her plump bottom starts massaging his shoulders. Girls are twittering about the dressing room, and a student from Temple University is interviewing the band with a cassette recorder.

During the second set, the band begins to feel magic rising. Everyone is synced together, drawing out songs with improvisations. At the end of a walloping chorus, Danny is jumping off the floor, guitar and all. John is bouncing like a dude, knees apart, head thrown back. The frenzy reaches the audience, making them wriggle and squirm. Song spills into song, until they arrive at Monster. It begins with strange, whirring noises and chords that build to a kind of electronic doomsday. John and Alan sway, their chins up, bodies dangling. Strobe lights flicker, faster and faster. When the music explodes, John is frozen in attitude, his head all the way back, his hands flayed apart in the air. It is as if he is suspended in a wind machine, at the still point, and the entire band is there.

It is snowing outside, at 1:30 A.M. The band hurries back to the hotel with a newly acquired flock of groupies. There is a lot of knocking on doors, tromping from room to room, smoking, drinking from a flask of Seagram’s apricot brandy, and watching television until the last station in Philadelphia goes dark at 4:30 A.M. Many of the groupies encourage rock stars to add whipping to their sexual encounters. One groupie called Ruby, an emaciated blonde with hooded black eyes on a vacant moon-shaped face, gave a young musician two sleeping pills, and the next thing he knew, he was tied with scarves to the four corners of the bed. Ruby, in black boots and a leather dress, was hitting him, just enough to sting, with the edge of a belt. “I flashed on it,” the musician said later. “I thought I’d take the trip, see what it was like.” The next day he tied Ruby up, “and she seemed to dig it.” That night he threw her out. “Groupies love to be treated like dirt.”

Michael says, “Most of the girls Rhinoceros has been meeting lately are interested in getting into whipping. You know, you take off your belt and kind of tease them with it, and then you start doing it harder.” John comments, “Whipping and bondage are symbols of the mental games that go on between us anyway—the possessiveness, the emotional sadism. There’s some of that in all of us.”

There is some of the groupie in almost every girl who watches a rock singer in leather pants and metal hardware, snapping his body and making a sound so loud it is very near pain. Only a small number, though, live out their desires to be possessed by rock artists. A San Francisco groupie made her compulsion explicit by having a gold ring put in her nose. The band members claim to dislike groupies, and pass them around like cigarettes. But groupies flourish in all the big cities because rock stars need them. They don’t bring wives or girlfriends with them on the road, because, they say, “the chick and the band end up fighting for the guy’s attention and loyalty.”

In Philadelphia, Billy and Roger Di Fiori, the road manager, pass up the girls for a Roy Rogers movie and the wrestling matches. They sit in their room all day, flipping the dials and gabbing at each other in Mad magazine talk. Billy is twenty-six, the oldest in the band, and has taken on the role of ringmaster, group therapist, and policeman. He came to Rhinoceros from the Mothers of Invention, which was the last stop on a train of rock groups: Buffalo Springfield, Thor ’n’ Shield, The Elysium Senate, Skip ’n’ Flip, The Medallions, and Ross Dietrick and the Four Peppers. One of the top drummers in the industry (he once worked three months as a timpanist in the Los Angeles Philharmonic), he is in high demand as a studio musician. Most people are frightened when they first see Billy—a round, grizzly-haired figure with a big stomach and bird legs. During a month on the road, Billy never wore anything but a pair of purple and blue striped pants with calico patches, a T-shirt, and a green cap, which no one is allowed to touch. When he climbs on stage, the T-shirt rides up and the pants slip down, showing the cleavage of his behind.

But Billy is the only one of Rhinoceros who finished college—a B.A. in music from UCLA. He learned bass drum in high school, when he still had other interests, like riding with the Hell’s Angels motorcycle gang. “I still have to get in a fight once in a while. When I joined this band they were afraid I’d either punch them in the mouth or light them on fire. I use that to keep them in line.” Billy complains that Rhinoceros has the problems common to every band with teenager’s in it. “All the kids have the mentality of a sixteen-year-old. They left home to make good and impress their parents that they were doing something.” Billy bawls out the band for yelling foul words in the hotel corridors, for belching into the microphones on stage, for setting off firecrackers in the parking lot, and for fighting over petty matters and ruining performances. “I’m willing to put as much time into this band as everybody else,” he says. “But after it’s all over, I want to go to Juilliard, to finish what I need for a master’s degree so I can teach music in high school. I want to get my own band of men. I want to become the John Cage, Stravinsky, Beethoven, Wagner, and everybody else rolled into one for this era, for this time.”

Among the thinkers of the band—Billy, Alan, and John—there is a conviction that rock is the primary musical expression of this time. Electricity, rockets, exploding neutrons, and instant communications caught up with popular music in the early 1950s, when gingerbread tunes like How Much is that Doggie in the Window? were bumped off the Hit Parade by Sh-Boom and Bill Haley and the Comets, whose Rock Around the Clock and Shake, Rattle and Roll cemented the phrase, “rock ’n’ roll.” Rosemary Clooney, Eddie Fisher, and Teresa Brewer faded quickly, rock dug in, and in the early 1960s, the whole way of popular dancing changed. The Lindy, the symmetrical one, two, back step, that had held through the first decade of rock, suddenly fragmented into the twist, the frug, the monkey, the string of dances named after animals and primitive sounds in which there is no touching between partners, only spasmodic jerking.

Alan contrasts rock songs with the symphonies of Beethoven and Mozart. “In Beethoven’s time, they had an hour to develop a work. Life wasn’t so—snap snap.” He pops his fingers. “The pace was more relaxed, and society was more ordered. Today, you have a three-minute song, it’s fast and loud, it sounds like the world around us. You go up on top of a skyscraper and look down at the city and what do you feel? Cha-cha Bohnng! a-Bohnng-a, bam Bam! Tchong tchong. That’s what you hear in rock.”

Over the door to the Electric Factory, Ben Franklin, who started it all with his kite and key, looks down his cardboard nose through pre-hippie wire-frame glasses. Saturday night, John has written a set that Danny doesn’t like. John wants to sing a number they haven’t done in a while, “because if we really get it on, we’ll kill the audience, and we’ll get it on us too.”

Danny says the song needs work. “Why can’t we do You’re My Girl?”

John says, “I’m sick of it.”

“Look, man, I playa lot of songs I’m tired of.”

“Yeah, but I’m the one that’s gotta get the song on vocally.”

Mike and Steve side with Danny. Doug and Alan are with John. Danny’s face is twitching. “I can see everybody getting uptight. Let’s stop it right here.” He cuts the air with his hand.

John stomps out, slamming the door. Steve throws a cigarette pack after him. Outside, John is raging. He crumples the paper on which he wrote the set. He hurls a record against the wall and steams back in. “I don’t know what to do. I don’t know how to write the set.”

Danny says, “It’s your uptightness that’s the root of the problem.”

“Okay, I’m uptight. Leave me alone.”

They are ten minutes late for the stage call. The scrubbed kids who paid three dollars to get into the Factory are talking and giggling in their seats. Danny goes back to the dressing room. “Are you ready?” John nods, weakly.

The set begins—the same songs as the night before, but they are dead. When it is over, the band walks off solemnly, straight back to the dressing room, no chatting or fooling with the chickies. The feeling between them is tangible, sexual, as between lovers who have seen a quarrel blow up over nothing and burn out, leaving them close and bittersweet.

Billy speaks first. “What went wrong is that we had a teenage quarrel.”

Danny sighs. “I just wanna forget about it.” His stomach is knotted up and cramped, and he needs to get the paregoric out of the car.

“You shouldn’t let John bug you,” Billy says. “John digs bugging people, isn’t that right?” John nods. Billy says, “When John gets uptight, let him tear his hair—when he does that, he’s getting rid of it. He sits in here writing a song, or a poem, because that’s what a set is, and you guys say you don’t wanna play it. He’s hurt, and I don’t blame him. I’d be pissed too.”

The door swings open. Two freckled boys wearing Western hats and kerchiefs announce, in little pubescent voices, “We’re from the Free Press. Can we talk to you?” Half the band walks out, and the two boys sit down. “What are your names?” Silence. “I’m Alan.” “I’m John.” And then, this great grizzly man who has ridden with the Hell’s Angels and groveled with the Mothers of Invention says, sweetly, “I’m Billy.”

“Any good group that can stick together can make it.” Paul Rothchild, a producer at Elektra Records, noticed in the fall of 1967 that a number of groups were breaking up and many others were having internal difficulties. He began wondering what would happen if he took one from this group, one from that, and put the best musicians together. Would it work?

Rothchild called every talented musician he knew and invited him to Los Angeles. His vision was of a supergroup of superstars, who would hammer a new approach to white rhythm ’n’ blues. He sent plane tickets to thirty, and on November 30, they began showing up at his house in Laurel Canyon. Alan Gerber flew out from Chicago. John Finley, who had recently quit Jon and Lee and the Checkmates, then the top group in Canada, walked into the white living room with its hardwood floor, fieldstone fireplace, and giant swimming pool visible in back, looked around at fifteen people he had never seen before and said to himself, “We’re gonna be a group?” John sat in the most distant corner and didn’t say a word. Neither did Doug Hastings, who had come down from Seattle where he was playing with the Daily Flash. Rothchild passed a guitar to a young man from Oklahoma and said, “Play.” Alan recalls, “It was great. Then he passed it to another guy, and he was great too. I was so spaced out that when they passed it to me, I said, groovy, and sang my songs.”

The boys stayed for several months at the Sandy Koufax Tropicana Motel, rehearsing at a rented theater. “We would jam in shifts,” John said. “It was dog eat dog.” Rothchild listened to the sessions, discouraged some people, brought in others, including Danny Weis and Jerry Penrod from the Iron Butterfly, Michael Fonfara from the Electric Flag, and Billy Mundi from the Mothers. By March, Rothchild decided the group was complete at seven members.

The name, Rhinoceros, came from Alan. It is his favorite animal. When the group played for the first time at the Kaleidoscope in Los Angeles, the sound was so loud and heavy that the name seemed natural. Two months later they went into the recording studio for eight days and made an album. Most rock groups spend close to a month in the studio, recording a few parts at a time and then dubbing voice and additional parts over that. The only way Rhinoceros wanted to record was live, all together, standing in a circle and playing into a cluster of mikes—one feeding back to them, the others recording.

Before the album was made, Elektra had spent $50,000 on the group, paying their room, board, and transportation, equipment rentals, rehearsal costs, and then buying out old contracts for three of them. The expense of making, promoting, and distributing the album raised the total to $80,000. By spring of this year, Rhinoceros had sold 100,000 albums. Not until they sell a quarter of a million will the band have written off its debt to Elektra and begin to earn money from the record.

In the fall of 1968, they decided to move to New York to build their reputation; there were more playing opportunities for the group there than in any other part of the country. The band lived in the cozily decaying Chelsea Hotel in New York for a few months, then found the house in Mahopac. About that time, Jerry, who was playing bass, started having fits of despair. One night in a town on Long Island, the band had a blowup before going on stage. When it was time to play, Jerry had disappeared. From information that has trickled back, the band says, Jerry “went straight—cut his hair, went back to art school in California, and moved back with his parents.” Danny’s brother, Steve, who had been working as equipment manager and had casually learned Jerry’s parts, was asked to take his place.

“It comes down to which one you want more, your freedom or their approval. I enjoy dressing and being who I am. It means more to me than going in that restaurant. I don’t need them.”

If no one else quits, Rhinoceros will be an unusual case. Even the most successful groups have been unable to hold together beyond a few years: the Mamas and Papas, Cream, Big Brother and the Holding Company, the Lovin’ Spoonful, Love, Traffic, the Byrds, the Buffalo Springfield. The list of casualties runs on, and the cause of death is almost always personal squabbles. Danny Weis quit the Iron Butterfly because of a fierce battle with the organist. “I can’t even remember the reason now,” Danny said. “Oh yes, he resented me playing leads more often than him.” After that Danny gathered a group that was to be called Nirvana, but before they could get off the ground, Danny fought with the bass player and the group disintegrated. The musicians wander, forming new groups, or becoming studio musicians, producers, or single artists.

Jac Holzman, president of Elektra, whose production is 70 percent rock, says it is difficult for a group to stay together more than a year after a record is released unless they see a steady increase in public acceptance. “The group hangs together by a string. It’s one gigantic holding action until the miracle happens.”

When success does come, it is a rare group that can stay on the road for more than three years. Holzman says, “Working on the road in dismal locations is demeaning, exhausting, and disheartening. Something has to be done to find better situations for musicians to play. Otherwise, no group can take the pressure of road performances.”

Friday morning at eleven o’clock, when the band is due to leave Mahopac, is the time everyone decides to do laundry. Alan discovers another rip in the only pair of jeans he wears. “Lan, could you do a fast patch job? If I don’t have my pants, I’ll feel insecure.”

Danny bounds up the stairs. “Cunnilingus, everyone.”

“Cunnilingus,” John calls from his room.

John has finished packing, and is staring out the window at the snowbound road. When John is feeling down, objects look ominous and distorted. He broods and wonders, “Why haven’t I ever been able to make it with a chick?” John is twenty-four, and the longest relationship he has had with a girl lasted three weeks. He drives the sixty miles to New York with the band every Sunday to go to The Scene, a rock club where groupies hang out, but rarely brings the girls back to Mahopac. “I don’t want to have to deal with them the next day.” He raps his fists against the glass. “Why is it that I reject people? Why do I insist on feeling alone and being alone?”

John is not the only one in the group who is, as they put it, “going through changes.” Danny also has been forced to look at himself with some care. Since he joined his first rock group at twelve, Danny has always had to be the star. With Rhinoceros, the stress was on playing together, rather than separately to the fans. Danny was called down, and made to realize, he says, “that I’d been on an ego trip for eighteen years, and that I didn’t really want to be the fancy lead guitar player whom all the chicks drooled over. When that happened, I stopped wearing all my satin clothes with lace and silks. I started listening to others in the band.”

Danny, like the others, learned music when he was very young. His father, John Weis, was a country-western guitarist who played with Spade Cooley and Tex Williams. His mother sang, and the whole family played at churches and naval training bases around San Diego. Danny was an honor student at high school, but left home at seventeen when his group, the Iron Butterfly, was offered a chance to play at a club in Hollywood. “We got $40 a week and lived in a room above the club that had no bed, no heat, and smelled awful.” He met a girl, twenty-five, who was a trapeze artist and stunt woman, moved in with her and got married at eighteen. The marriage ended two years later.

“Being married to a musician is tough on a chick,” Danny says, “You sit at home every night by yourself while your husband is surrounded by chicks who throw themselves at him. I learned from being married that you have to get all the sex thing out of your system, because the music is so tied up with sex that it’s a real struggle, even if you’re married, not to go after it.”

The language, the argot of rock is grounded in sexuality. The instrument is your “axe.” What you play on it are “licks” and “chops.” If two players get into competition, they “fight each other with their axes.” A band gets on stage to “get it on,” “put it together,” “be together.” If you “dig” something, you “flash on it,” “turn on,” “get into it.” Something serious is “heavy,” something relaxed is “laid back.” A girl is never called a girl, she is always a “chick.” The male is a “cat.” They manage to express a fairly wide range of feelings with a vocabulary so narrow that when John tried to explain a subtle relationship, he stopped in frustration. “This is terrible. My grasp of English is slipping away.”

The communication between band and audience is as physical as it is aural. Steve says, “I know certain lines on the guitar that, if I’m interested in a chick, I can look straight at her and do it to her. This one line starts high on the neck of the guitar and goes down to the lowest part, fast. It’s like a slap in the crotch.” When Mike works on the organ, he is thinking of making love. “The beat does it to me.” And Danny says he gets so sexually and emotionally excited that, “I’ve come on stage lots of times, just from the music, and it’s unbelievable. Sometimes I fall off the stage, and other times, I cry, right up there.” Jimi Hendrix, feeling the same surges, set fire to his guitar. Jim Morrison of the Doors sang Touch Me and then is alleged to have exposed himself on a Florida stage.

After a set, the band waits for girls to approach them. “You’ve made the first move by playing. It’s up to them to take you up on it.” Steve knows musicians who by the time they were seventeen had more experience with sex, drugs, and drink than many men have in a lifetime. One started sniffing glue at eleven and, by fifteen, had tried marijuana, speed, LSD, barbiturates, mescaline, opium, hashish, and every kind of trip chemically possible in the drug culture. He had also had groupies in combinations of two and three. Steve’s own father had died when the boy was fourteen, and Steve was shunted from school to school as a problem child. When he paid attention, he gave evidence of brilliant perception, but, he says, he was stoned almost every day he went to class. At sixteen, he convinced his mother to let him go to Hollywood to live with his brother Danny and his wife. Danny, then eighteen, became Steve’s legal guardian.

All of the band members believe they will have to get out of the atmosphere of drugs and sex some day. Danny tried meditation with the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, but found that “that way of life doesn’t go with rock ’n’ roll.” The boys’ view of the future barely stretches beyond six months. When asked what he would like to be doing in ten years, Alan was silent.

“Well … the most important thing for me is, I just wanna go off and live in the country, in the woods, and find peace with myself. I wanna write and play my music. And I won’t be smoking dope. I’ll be eating health foods.” Doug, in his soft, composed voice, says, “It’s impossible for me to say what I’ll be doing when I’m forty. I think you can have a good life doing anything in the world, if you want it badly enough and don’t cop out to your paranoias.”

Danny says he will play guitar the rest of his life. He watched his father, who was “the best guitar player there was,” become an insurance salesman to support his family. “It killed him. I saw him die from it. He wanted to play music and he had to sell insurance. I knew I could never do that. I said to myself, fuck it, I don’t care if I starve. I’m gonna play music until I die.”

Friday night in Schenectady, the marquee in front of the Holiday Inn says, “Happy Birthday Peggy.” Watching television in his room, Danny picks up the electric guitar and tries to get Michael’s attention. The guitar is barely audible when not plugged in, but after several minutes of crazy whirling runs, Mike turns his head away from The High Chaparral and drawls, “You’re insaaaaaane.”

When the guitar is plugged into an electric amplifier, it works like this: the musician plucks the strings, causing them to vibrate. The vibrations are picked up by a set of small magnets under the strings and sent as electric impulses through a cord to the amplifier. The amplifier magnifies the impulses, converts them back to musical sounds, and feeds them out a speaker. Each guitarist uses a separate amplifier, and will use two or three in a large hall to make the sound louder and fuller. Michael’s Hammond organ needs a special Leslie organ amplifier and several mikes in front of it. Alan plays a Rocky Mountain Instruments electric piano which has its own amplifier. The vocal parts and drums are not amplified, but carried directly over a public-address system. Most bands amplify themselves up to the point of distortion. It is always different to hear a group live than to hear them on records, because the volume transforms the experience. Even between numbers, there is a constant electric buzz. “It’s security,” John says. “The louder you are, the more confident you feel, especially in a strange place.”

Schenectady, a depressed industrial town in central New York, is not only strange but grim. The job is at the Aerodrome, a warehouse converted into a seedy psychedelic nightclub. Girls with troubled complexions, wearing cheap hairpieces and elephant pants, flail about by themselves on the dance floor. In the room that Rhinoceros must share with a local group called The Pumpkin, John begins to write the set. The band’s repertoire is twenty-five songs, all but two of which are their own compositions. The lyrics are simplistic, juvenile, with the limited scope of 1950s rock—I love her, need her, miss her—but with none or the existential wit of the Beatles’ simple songs. (But then, in their early years, when the Beatles were the age of Rhinoceros, their subject matter was not much more sophisticated: “I Wanna Be Your Man,” “I Want to Hold Your Hand,” “I Saw Her Standing There,” “All My Loving.”)

While all the members of Rhinoceros have agile minds, none of them reads anything at all. Four had extensive training in classical music. Michael taught piano at age twelve, and Alan was composing chamber music at Chicago Musical College when he quit to join the band. But they don’t read. It’s as if the print medium, with even lines, is too confining and laborious. Danny says, “My mind is always going so fast I can’t get into books or stories or anything.” Neither do they have any awareness of politics. “We don’t have any idea of making revolution,” Danny says. “We just wanna make people feel good.” The social commentary that seeps through their songs is instinctive, rather than conscious, as in John’s Top of the Ladder:

You read about it in the paper every day,

Someone’s always climbin’ up that ladder,

and makin’ a big scene.

Now baby I know just what I need,

I’ll see you at the top—of the ladder!”

The sets at the Aerodrome go well. John is ebullient when he comes off stage, but Alan is depressed. “This is the kind of place that makes me hate playing rock ’n’ roll.” Danny is sitting stone still. “It’s weird out there,” John says, “Maybe I was wrong. I felt great singing, but since I’ve been off stage…” He goes out to the bar, and a shrill-voiced girl says to him, “I’m not very pretty but I’m fun to watch,” and starts twitching her pasty face. “Shit.”

Boston is better from the start. “The whole thing feels special,” Alan says, halfway along the Massachusetts Turnpike. No one in the band knows exactly how to get to Boston. On the itinerary handed them that morning, there are no directions, no time listed for sound checks or performance, and the hotel is misspelled, “Sheriton Boston.” Even if they had directions, they would probably lose them. They lose everything—letters, tickets, keys, money, phone numbers. The Boston Pop Festival, the itinerary says, is at the Boston Armory. When they find the armory, it is boarded up and dark. The festival, they learn after driving around for several hours, is at the Boston Arena. No one in the car is worried or nervous. They are all soaring.

Danny describes the perfect gig: “A good gig is going there, being happy in the car, and feeling well healthwise. I usually ache all over, have a headache or a backache and very little energy, mainly because I don’t exercise. All I do is sit, sleep, and eat. The next thing is getting real smashed before the gig, playing a magic set, meeting really pretty chicks and having a groovy thing at a Holiday Inn, or some other hotel that has good, hard double beds, so they’re good for my back. That’s a good gig.”

For John, a good gig is building up emotional power over the audience. “To do that, you have to live the music, not perform it. If you sound sad, you have to feel sad and be sad. If the spirit and emotion is there, you can make people jump out of their seats, cry and scream. That’s what gospel music does for me. That’s how preachers earn their money. When I was playing with the Checkmates, we’d have so much power, I could touch people one hundred yards away, reach out with my hand and touch them with my soul, and they’d scream. One gig we did, there was a killing while we were on. I don’t know what that means, but it happened. It was, well, curious.”

The Sheraton Boston is riotous with fountains, suspended staircases, tropical plants, and Peggy Lee singing Fever over the Muzak. The band doesn’t usually stay in hotels like this. They prefer motels that are easy to get in and out of. The first carload walk into the lobby in their freak clothes and hair falling to their shoulders, and the lobby turns, as if the hundred or so people milling about are one body.

Steve is the most conspicuous. He is all in black, with a black satin shirt open to the waist, a large silver and turquoise cross bumping against his concave chest, and black, crushed velvet pants. Over his pale face is a black desperado hat with a low crown and wide, curving brim. Alan is wearing a blue and green flowered satin shirt with puffed sleeves, a green suede vest, and his jeans with the leather patches. His silky brown hair hangs over his eyes, and together with his sideburns and moustache, completely dominates his appearance.

The hotel manager refuses to give the group rooms until they pay in advance. They try to eat dinner, and are turned away from all four restaurants in the hotel for lack of coat and tie. They drive to a restaurant called the Red Fez in Roxbury, frequented by shaggy students from Brandeis and Harvard. A waitress comes at them holding out her arms. “I’m sorry, we’re closing.” A sign in the window says, “Open until 3:00 A.M.” It is long before 3:00. The waitress is glaring at Danny with his white, cat’s fur hair and Steve in his black satins and desperado hat. “Yeah, we understand,” John says. The band doesn’t press trouble. They leave quickly. This is the dues they pay for living outside, for not keeping a foot in the other world. No one in the group owns a tie. “It comes down to which one you want more, your freedom or their approval,” John says. “I enjoy dressing and being who I am. It means more to me than going in that restaurant. I don’t need them. They’re the cretins.”

Giving up on dinner, they drive to the Boston Arena, an old roller rink, filled with mildewed air and dirt. “It looks terrible,” Steve says, as they fight through a jam-up in the parking lot. The policeman at the gate doesn’t believe they are Rhinoceros, and holds them aside until an official is summoned. The group still hasn’t found out what time they’re going to play, and it’s too late now for a sound check. They are escorted to their dressing room, a musty green cell with a bank of toilets, showers, and dirty sinks, in which a dozen Cokes have been placed. “Aaaaggh, it’s a latrine,” Steve yells. It is 9:00 P.M., they are to play in thirty minutes, and half the band hasn’t shown up. “Let’s not get worked up over it,” John says. “We’ll just upset ourselves.” The other carload walks in with ten minutes to go. They had been stopped in Connecticut for speeding, taken to the police station and arraigned, then had gotten lost on the way into Boston and driven right through the city and out for ten miles before they realized it.

Rhinoceros is third on the program, after Daddy Warbucks and the Grass Roots. They will be followed by the Caldwell-Winfield Blues Band and Canned Heat. The Arena, they discover, is an “echo bomb.” The bleachers are half filled—about a thousand people huddled in coats against the drafts. The vast spaces in the building make it impersonal. With ticket prices $5 and $6.50, the audience is practically all white. High school students are running down the aisles and talking above the music.

The whole band knows, though, that they’re going to have a good time. In the first number, they throw back their heads, laugh and call to each other. Danny starts his rounds, moving up to John and getting into rhythm with him. Then he faces Steve, who nods his wilting head at Danny, “Mmmmmm, Yeah!” and then at Billy, in his green cap and dark granny glasses. John begins to lose himself in Top of the Ladder, jumping, skipping, snapping his body in half with the downbeat of the drums. When the song ends, he mops himself with a towel, then grabs the mike. “Hey, wanna catch some ass, wanna get it on?” Laughs, and a few jokers yell, “Yeah.” John says, “Let’s catch some ass,” and Danny hits Apricot Brandy.

There are hearty boos when John says, “We’ve only got five minutes left. But we’d like to go out stomping.” Everyone in the band except Billy stands up now and pounds the floor, Thwack! Thwack! clapping their hands and waving tambourines. They keep up a rhythm, two minutes, then Danny waves at Billy, “One, two, three, go!”

Through the song, You’re My Girl, the band is jumping, waving their free arms, grabbing anything to shake—sticks, bells. Michael is playing the organ standing up, bouncing and yelling. The kids in the front rows are on their feet screaming. Even the policemen in front of the stage are nodding, their white caps moving, ever so slightly, up and down.

When the band finishes, dripping wet, people rush at them and grab their hands. They make their way to the dressing room, sigh and collapse.

Alan: “I had such a good time!”

Mike: “Oh, fuck, it was so good.”

Steve: “We kiiiiiiilled ’em!”

John: “It feels so great to crack a challenge like that. Those people didn’t wanna move, and we made ’em wiggle asses. We really had to work at it.”

They close the door, and sit together in the musty room with its urinal smell. Their bodies are limp, their eyes glazed, fixed on the ceiling. They smile, and blink, and every now and then make this sound, a soft, airy sigh, which is the beginning of a laugh: “Aaaaaaaaaahhh.”