Waiting for the opening tip-off, in that eternal moment before life begins, he stands motionless, his body achingly still, permitting only his eyes to move, hazel eyes darting about the arena, welcoming and fearing familiar faces and new, noting the loud-mouth gambler in the fourth row, the blonde with the little skirt beneath the basket, the kid with the Barkley for President sign at half court. While the other athletes remain in a cocoon of cool, Charles notices all who notice him, and all who don’t. His menace masks his insecurity. Shy, he is still the fat kid from Alabama looking around the school auditorium for the father who left home when his son was just an infant. He hears his own heartbeat, as he will soon hear every epithet, every encouragement; the former will burn, the latter soothe. The game cannot start soon enough. Playing basketball is the easiest part of playing basketball.

The ball is tossed into the air. When it returns to earth, the child is a man.

Minutes into the second quarter, Barkley is called for a defensive foul, smacks himself in the head, twirls all 360 degrees of outrage, stomps the floor, emits loud agonized sounds, looks to the heavens for salvation. It’s a 270-pound temper tantrum. Why they do me like this? Had anyone not been watching him before, they are now. He is the cynosure of every stage he stomps upon, the ultimate scene stealer. And chewing all that scenery will cause weight problems. He’ll be the roundball Brando. If his paroxysms weren’t enough, the threat of remonstration defies you to look away. His hair-trigger emotions have no safety mechanism.

Does he really pack a pistol?

Both on and off the court, of two things Charles is certain: no one will out-talk him and no one will intimate him. Charles gladly shares his thoughts and feelings with referees, opponents, teammates, strangers. Bright moments and dark calamities inspire high fives and constant commentary. Prolix and intimidation are a one-two punch. His unique physique somehow occupies more space than a 6’4” frame ought to and can cause more disruption than you expected, all the while distorting notions of big and small. Manute Bol we can comprehend, and Spud Webb too; sure, they may be comical when back-to-back, but each does what a man his size should do. They make sense. They make you feel normal. Charles Barkley is a cuddly befuddlement, a miniature enforcer, a monster guard, a leaping bowling ball, and race track tank. What to make of him?

Near the end of the first half, a jump shot is missed and Charles clears the rebound from a crowded rim and a behind-the-back dribble inaugurates one of his reckless, rambling transcontinental excursions, the kind that begins with shirt-tail flapping tremors that excite the fans and send scientists to their seismographs and coaches to their pillboxes, the kind of rumble that will climax only when large chunks of humanity have been parted to allow the manchild to deposit the ball in a most violent fashion through the metal hoop at the other end of the world. Yes, the earth moved! Aftershocks rattle the arena!

When you’re a 5’10” outcast in high school and forced to practice alone by Dixie moonlight on a court behind the projects, you learn an angry, solitary brand of basketball; denied the ball and the spotlight for so long, once in possession, you refuse to relinquish either. Charles Barkley plays scared and mean. He is the shortest man to lead the NBA in rebounds. Ever.

You can’t stay angry at Charles very long, not like Darryl Dawkins or World B. Free. Barkley’s talent and charisma prevent any sustained grudge.

But does he really carry a loaded handgun?

His splendid outbursts seem to follow a missed three-pointer or an ill-advised flashdance. You can’t stay angry at Charles very long, not like Darryl Dawkins or World B. Free. Barkley’s talent and charisma prevent any sustained grudge. He succeeds too frequently, works too hard to hate. The terrible twos will pass. Besides, one of his whirling dervish routines is worth the price of admission, a welcome reminder that some primal force is still extant on planet earth. Aggression so calculated and naked affect his teammates as much as spectators; they too stand in unholy awe, inflamed by his sheer audacity, propelled by his energy.

Who pines for Dr. J at these moments?

Charles can’t even palm the ball. So he resorts to a two-fisted kind of game. In yo’ face is too polite. He’s up your nose, deviating your septum and shooting out your skull. If Air Jordan glides over the masses—with tongue mocking—Ballistic Barkley slices right through you, dares you to become the immovable obstacle. You watch Jordan slither and snap his way to the hoop all night and are surprised he scored 52 points, felt like 30-something. Every Barkley point is seen, felt, suffered. No one sleeps through a quake with an epicenter named Charles. Only 36? Felt like 52. Few were cheap, fewer still go unregistered. He may be the only player who shoots three-pointers from inside the key and above the hoop.

Comparisons to Jordan are false, of course, but inescapable: two distinctly solo performers put up big numbers and pull down too few wins. Do they use more energy than they produce? Can you build a team of scarecrows around a wildfire? Last season, Michael sat Charles down and told him the word around the league was to let Barkley score as much as he wanted—the Sixers would fall. Michael knew of what he spoke. In Chicago, they wonder if the Bulls can win with such a spidery scoring maestro; Jordan wonders how scoring less would help his team win more.

The same question was asked when Wilt filled the middle or when Dr. J flew into town. Wilt’s dominance turned his teammates into statues. Aficionados appreciated the Doc’s artistry but suggested he was too idiosyncratic to lead a team to victory. What good is inhuman hang time when you land in second place? And how can anyone follow that jazz? They asked Doc to please pass more and please rebound more and—for God’s sake—please win. It was like telling Sonny Rollins to tone down his solos ’cause the rest of the quintet can’t keep up and the records don’t sell well anyway. Sonny told them to get better sidemen or hire a different leader.

Sonny was not the statesman Dr. J is.

“Charles is this and Charles ain’t that. Damn. That shit works on you. You’re mad as hell because you hate losing and you’re struggling for your life and it’s brutal, just brutal.”

Barkley is painfully aware of the paradox. He shakes his head and says, “Everyone came at me last year with, ‘You’re the leader, so what’s wrong with your Sixers?’ I knew I was gonna get the blame. The first year without Doc, it’s my team. The Daily News says we can’t win with me as leader because I’m not responsible enough. Charles is not mature. Charles loses his temper and he’s not the leader type. Charles is this and Charles ain’t that. Damn. That shit works on you. You’re mad as hell because you hate losing and you’re struggling for your life and it’s brutal, just brutal.”

He’s 25 and accused of being young. He’s named co-captain and told he’s not a leader. He’s the best player and hardest worker on the team and blasted for not being more.

“I don’t like being responsible for the whole team,” he says, “I can’t carry the team. It can’t be done. The normal knucklehead on the street doesn’t understand that it’s a team, a chemistry, not a one-man show. People say since I took over the team, it’s going downhill. I know this. I’m there. I play my heart out every night. And damn, that shit hurts. I will never let happen what happened last year, not making the play-offs. I guess I didn’t do right. I should’ve done something. If you’re a great player and the leader and everybody feeds off you, you have to do something. And I’ll do it. I’m just not sure what that is.”

Early one morning this fall, Charles called his grandmother, Jonnie Edwards, from an airport in Texas and told her he was bringing some friends over for dinner. His grandmother lives near Leeds, Alabama. At 7 PM that evening, the entire 76ers team was eating barbequed butt and baked beans with their co-captain’s mom and grandmom, his two best girls.

Barbequed what? “Barbequed butt,” repeats 63-year-old Jonnie Edwards.

“It’s pork sliced real thick, like roast beef. Charles’s mama made fried chicken and baked beans—Charles loves his mama’s baked beans—and I took care of the barbequed butt. And we all watched Monday Night Football. It was a fine night.”

Jonnie Edwards loves sports. Especially basketball. Played on her high school team, taught her grandson everything he knows. It tickles her when Charles plays most assertively. That’s how underdogs play. Since her favorite college team was Auburn, always the underdog, that’s where Charles matriculated. They still talk nearly every day. Sports mainly. She really liked Charles bringing the team to dinner.

“My first season with the Sixers,” says Charles, “after the final game, everyone said, ‘So long, see ya next year’ and split. Next year? What the fuck is that? I thought teammates hung out together and were friends. This was not my idea of team. I try to keep everyone on the same wavelength. We have a close-knit team now, friendly, down-to-earth. I love my teammates.”

Mike Gminski and Chris Welp are Barkley’s best buddies on the team. He saw them, and some others, often in the off-season. Charles allows friendship no summer vacations. And when Scott Brooks needed a place to stay, Barkley insisted he live with him. Charles remembers his own rookie season, when Philadelphia was cold and inhospitable. He lived in a hotel until he found an apartment in the Northeast. He rarely ventured out. Nowhere to go and nobody to go with. He had never been so far from home for so long. There were lots of phone calls to Leeds, Alabama.

“Charles has changed since he joined the Sixers,” observes his mother, Charcey Glenn, who still works as a housekeeper two days a week. “He has adopted a tough attitude, not like when he was home. Leeds is a small town, where people wave to you when you pass their house. Charles was raised to trust people. He was very naïve when he moved to Philadelphia, very naïve. Here in Leeds, white and black work very nicely together. We still leave our doors open. We’ve had our share of trouble but not like other places. Not like Philly. Charles used to think everyone was nice. He’s learned a lot lately.

“Charles is growing up.”

“Two Diet Cokes,” says Charles to the waiter. He is having lunch with two former teammates, one white, one black, one from Auburn, one failed Sixer now trying out with the Houston Rockets. An all-pro, a no-pro, and a fringe-pro. The various levels of success are lost on none, nor left unspoken. There is constant teasing, jockstrap japery. Charles dishes it out and receives it with equal felicity. Various parts of this body serve as ample targets for street slings and arrows. In order to lose weight, it is suggested, Charles should deflate the helium in his head, lopping of 30 ugly pounds, and then donate his head to Harvard.

When not being taunted about his fluctuating poundage, his head takes a pounding: he is addressed as Airhead, Melonhead, Big Baldie. Technically, he has lost no hair yet keeps it so peach-fuzz short that is appears painted on, the paint cut with thinner so that light bounces off his dome. It’s shorter than his two-day stubble. The greatest concentration of hair on his head, despite his attempt at a mustache, can be found in his thick, caterpillar eyebrows.

“Four more Diet Cokes,” he tells the waiter, “and a salad, lettuce only, no dressing.” Barkley is as amazed as anyone that a young guy can play full-tilt basketball, perhaps the most demanding of all professional sports, and have to worry about weight. Still, his new half-million-dollar house is devoid of exercise equipment. He resolutely refuses to play basketball during the summer. He’s too exhausted and too high-strung. “One day, you’re playing against Larry Bird in the Boston Garden, next day you’re playing against Sam Sausagehead on some playground. No way.”

Current weight? Twohundreseventysomething. The Sixers brass bug him continually. They make comments in the newspapers. They say they fear his playing days will be limited by carrying too much weight. As long as there’s a weight clause in his contract, he’ll have trouble making weight. As long as the Sixers fine him for criticizing the team, he’ll continue to speak his mind. What they may not know is that Charles’s stomach is a measure of his mind, that indulgence at the table promises indulgence on the court. He went over 300 pounds in college. When he sulks, he fills the emptiness with food. When things threaten to eat him up, he eats them first. He will not be intimidated.

“A plate of chicken wings,” he now orders.

“Why all the grease?” asks one friend. “Why not something healthy?”

“We’re all gonna die,” says Charles. “You be eating your whole wheat and sprouts and you gonna die, too. I’m gonna die happy.”

“The question is not whether you’re gonna die, Melonhead, but when. You ain’t gonna see the year 2000 the way you eat. 1999 and good-bye!”

“I ain’t afraid of dying,” says Charles. “I live right next to a cemetery. I like it. I don’t lose sleep cause of my neighbors are partying. I got very quiet neighbors.”

“I thought you said you didn’t sleep last night?”

“It wasn’t my neighbors—it was my girlfriend. I watched two movies, fell asleep about four and then she woke me up with morning sickness.”

“I’ll never have two bad games in a row, never. It makes me feel inferior. I don’t like that feeling. I want to be exceptional.”

Charles wants children. Lots of them. They talk of marriage, Maureen and Charles, and then they talk about bodyguards. Maureen is white. Charles is scared. He constantly worries about the Knuckleheads Out There. Two women approach the table, and timidly ask for autographs. Charles obliges, admiring, out loud, a short black leather skirt. The wearer of the skirt is pleased. There will be, throughout the meal, a steady stream of autograph seekers and well-wishers. All will be treated graciously, if suspiciously. Adulation is a low-cal side dish.

Does he have the gun with him now?

Waiters stop by to kibitz. Charles knows them all by name. He eats out often. Mostly fast food joints in the tony suburbs along City Line Avenue. He is on a first-name basis with maitre d’s and busboys. They will attest to the sweetness of his disposition. A bartender at Al. E. Gators provides typical profile: “Charles is the nicest athlete we get in here. Totally without façade. The direct opposite of those assholes from the Phillies, Von Hays and his arrogant bunch. Charles is always respectful and friendly. He goes into the kitchen to say hello to the cooks. They go crazy. They love Sir Charles.”

Pat Crane is the interior decorator working on Barkley’s new house. She calls him the ideal client, courteous, trusting and funny. “A couple days after he was arrested for the gun incident, he left a message on my machine: ‘Oh my God—I got one phone call from jail and I can’t reach my interior decorator!’ Charles is one of the nicest people I know. I think he’s basically shy. When we go to buy furniture, and his taste is very conservative, kind of gray flannel, it’s like going out with the President. People are drawn to him like a magnet. Especially children.”

Dave Coskey, public relations man for the Sixers and the kind of guy who chooses godparents very carefully, chose Charles Barkley.

So how can this bashful kid with a Buddha nature turn a game of hoops into guerrilla warfare? Most won’t venture a guess. Journalists call him complex. Friends shrug and leave it at “Charles is Charles.” And Charles fascinates in the deep, supernatural way of Jekyll and Hyde or Clark Kent and Superman. When he ducks into his locker and changes into his red-white-and-blue uniform, he emerges as a different cat. From man to animal. From fact to myth. A clean, extreme metamorphosis.

A tall woman approaches the table. Charles sees her coming. Her charms are obvious. Charles discreetly comments on her physicality as she smiles and saunters by silently. One wonders how Sir Charles has circumvented female trouble, especially on those long and winding road trips.

“Hell, the fans would turn on me in a minute,” he says. “I have to be very careful. I refuse to get caught up in the nightlife, which basketball definitely offers. You finish a game and can’t go to sleep and you go out to eat and stay up till three in the morning. You don’t have to be at practice till noon the next day. And all the towns are jumping. The only real bad town for nightlife is Cleveland, real bad, with the hotel in the middle of nowhere. Portland is great and Seattle, too. Boston is easy. Los Angeles is the best—the woman are something else. That’s a dangerous place. Philly’s all right. If you are an athlete in this town, you’d have to be blind and paraplegic not to get laid whenever you wanted.”

“I must be blind,” says the former Sixer, “cause I ain’t paraplegic.”

“You just too ugly,” says Charles. “Anyway, I said athlete.”

“If I ain’t no athlete, how come I whupped your ass this morning, one-on-one?”

“I was tired. Now I got some food in me, you’re a dead man.”

“Rebounding is like Christmas. They know I’m coming.”

After another Diet Coke, Charles posits that there is no such thing as a friendly game, not golf, not poker, not tiddlywinks. “As soon as you accept losing, you’re finished. You start a pattern. Coach can scream at me and it don’t mean shit, but when I get mad at myself, then I’m ready. I’ll never have two bad games in a row, never. It makes me feel inferior. I don’t like that feeling. I want to be exceptional. And I know how it works; this society is so sick that you are judged purely winning and losing. You lose, you’re shit; you win, you’re great. I can’t feel like shit. I don’t like that feeling. Personal honors are all right, I’ll take them, but without winning, feel empty. I don’t like empty.”

Charles eats to avoid empty. Charles plays to fight empty. Charles runs from empty of any kind. His gun had 13 live rounds when he was pulled over by the state trooper.

The check arrives. Charles grabs it as naturally and forcefully as a rebound. He used to be generous to a fault. Now he’s wary to a fault. “People always want money from me. Friends and family come out of the woodwork. And I can’t say no. I have at least $50,000 out there that I’ll never see again. Friends ask me for $5,000 or $300 and they say it’s not a lot of money to me, and they’re right, but if I say yes ten times, it adds up. My mother and my girlfriend say I’m the worst person in the world at saying no. I have just learned, just last summer, to say no. I’ve matured so much, it’s sad. I used to hear that you don’t change with money, the people around you change. I believe that. Everyone treats me different now. I want to help everyone because, deep down inside, I want people to say there’s been no change in me. I don’t like change.”

The waiter interrupts, handing Charles a plate of money. “Your change, sir.”

The players are all wearing Santa hats. They’re calling for Mo Cheeks to stop shooting foul shots and join them for the team portrait. If Mo Cheeks could avoid this, the shyest Sixer of all, he surely would. Now Harold Katz calls out to him. Katz is on a ladder next to a Christmas tree. It makes him higher than any of his players. The owner is wearing the whole Santa Claus outfit for the team’s Christmas card. The photographer finally moves Mo Cheeks in the right spot, and Cheeks whispers something to his teammates. There is a ripple of muffled laughter. The owner wants to know what’s so funny. Barkley takes delight in passing along the punch line.

“You look like Santa, boss, but you sure don’t pay like Santa.”

“I built this whole life on not being poor,” he says matter-of-factly. “We were so dirt poor when I was growing up that we didn’t have a shower. I decided long ago never to be poor again. That’s why I left college early.”

Barkley would never pass up a chance to zing it to the man, proving that some things do not change. The first time the Round Mound met the Sultan of Slenderizing (Katz owns Nutri-System weight loss products and services), the boss challenged the college kid to lose seven pound by the NBA draft as a show of good faith and self-discipline. The kid had a whole month. Katz didn’t know with whom he was dealing; maybe he still doesn’t. The Round Mound got Rounder. You don’t challenge Barkley by telling him what to do, but by telling him what he cannot do. Limit him, sell him short, cut him down and he’ll die proving you wrong. As long as there’s a weight clause in his contract, he’ll have trouble making weight. As long as the Sixers fine him for criticizing the team, he’ll continue to speak his mind.

Child psychology only works on adults.

“To be my own man” is a phrase Charles uses again and again. Reared by two strong women since his parents’ divorce when he was a year old, he has had to be his own man in one way or another. He may charm civilians with his oceanic smile and inviting countenance, but he has a terrible time with male authority figures. No wonder he has never seen eye-to-eye with any coach he has ever played for. Not Sonny Smith at Auburn nor Bobby Knight at his failed Olympic trial. “I’d like to have 10 minutes in a locked room with Bobby Knight.”

Asked what he learned by being benched by Billy Cunningham in his rookie year with the Sixers, Charles says, “You can learn a lot just sitting, watching, like I should be out there playing the damn game.” Coach Matty Goukas couldn’t control him and now Jimmy Lynam is reportedly enjoying a serious rift with his star. Joy to the world.

One hopes that Katz’s Barkley is bigger than his bite. Some pair they are. Charles and Harold, a talker and a tinker. They used to play tennis until Charles gave it up for golf. He lost consistently to his boss, which might have contributed to his switch. He really does loathe losing. What a scene that must have been—the undisciplined banger in the gray sweats and hi-tops versus the methodical stroker dressed in white with years of private lessons under his belt, each trying to control the game, to outfox and outhustle his opponent. Two poor kids who scratched their way to wealth by playing nasty. They must respect each other. Millionaires tend to respect each other. Each secretly understands what the other is going through—that special sadness that comes from getting what you always wanted only to find it’s not the way you always wanted it to be. Ho, ho, ho.

The bigger the front, the bigger the back. Old Buddhist saying.

“I seriously considered not playing this year. I was going to retire. Or sit out a season. Last year was pure pain, horrible, just horrible. First, we didn’t make the playoffs for the first time in 13 years. Then the trade business. My agent was under investigation. And then the gun thing. It was all too much. A year without joy.”

If a single bad call can cause Barkley to grimace and dance an anguished jig, imagine what a season of bad calls in bad games with a bad team did to his psyche. He either conjured up a trade as a cure or was privy to inside information.

“I know the front office was discussing me with a few teams, I said so, and everyone was pissed. I just happened to be in California for the Special Olympics when the Sixers were discussing me with the Clippers. The Clippers had a couple of first-round draft choices, and they like me a lot. I know that through friends who work for their organization. I want to stay here. I love Philly, but when I bring this trade thing into the open, the Sixers deny it and all I hear on the street is, ‘We hope you get traded.’ Damn! I don’t understand any of that shit. I never said I wanted to go.”

The Sixers deny to this day they ever talked to anyone about Charles.

Lance Jay Luchnick is denying nothing, at least to the press. Barkley’s agent and financial adviser since turning pro is under investigation by both the NCAA and NBA. Luchnick reportedly gave thousands of dollars in cash and gifts to high school and college coaches to help him procure clients. The NBA Players Association found Luchnick’s conduct in “flagrant violation” of their regulations and placed him on a year’s probation while they investigated further. Luchnick is the first agent so monitored by the NBPA.

Though friends had been cautioning Barkley about his agent—Mo Cheeks has already dropped Luchnick— it took bad news to force him to audit his own agent. Barkley says the process was ugly yet rewarding; everything checked out. And though Barkley reports all this calmly, uncharacteristically taciturn, his stomach churns at the prospect of losing his financial stability.

“I built this whole life on not being poor,” he says matter-of-factly. “We were so dirt poor when I was growing up that we didn’t have a shower. I decided long ago never to be poor again. That’s why I left college early. I remember at the NBA Draft thinking, ‘Now I’m gonna get better and earn some real money.’” He earns about $1.6 million a year now. He wants more. Much more.

With money comes fame, with the fame, power. In customarily contradictory fashion, while vociferously abdicating his status as role model, Barkley happily lectures kids against drug use; with a crusader’s fervor, he scoffs at addiction-as-a-disease and blames it on weakness. Having seen friends fade away in a cloud of while dust, he invited random testing by the league, despite the players union’s caveat against it. Cocaine is easy for Charles to deal with: it’s illegal and, over the long haul, deteriorates one’s talents. Steroids throw him, he admits, disapproving of them yet defending anyone’s right to use the legal drug to enhance his performance.

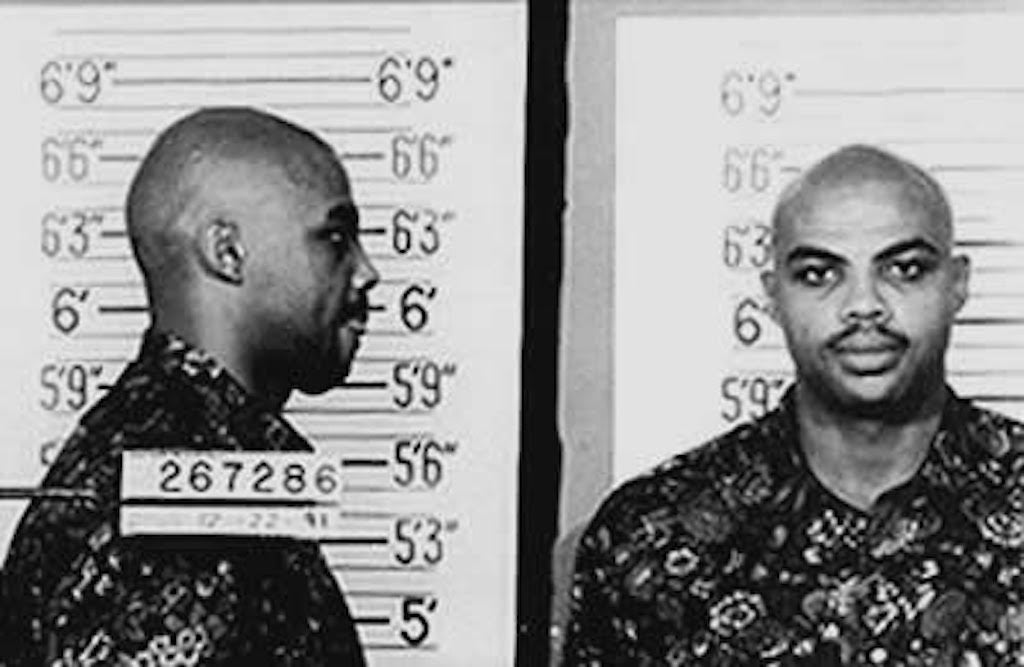

Barkley was happy to drive to Atlantic City to warn 500 kids about the danger of drugs at the West Side Complex, an elementary school and community center. On his way back to Philly, the crusader was pulled over by Desiree Simon, a Jersey State Trooper. She saw a black man behind the wheel of a $75,000 Porsche and just knew there were drugs involved. She asked the driver to step out of the vehicle. She searched the car (illegally, it was later determined) and found a loaded 9mm Heckler & Koch semi-automatic pistol with 13 rounds sitting on the floor behind the passenger seat.

Why they do me like this?

“The media got me pissed off,” says Barkley bitterly, no fan of the daily press to begin with. “Especially the Daily News. Some of their writers love it when things are going bad. I really believe that. It has to do with their personalities—they dig adversity. I don’t like people writing about basketball who never played. They can’t know what I’m going through. A lot of these guys are jealous. They try to control you, to make you and break you. All I ask is fairness. When I play a good game, say so; when I stink, say that.”

Beat writers and athletes share a weird love, heavily laced with dependency and resentment. The players can be tight-lipped and thin-skinned, the scribes lazy and sensationalistic. They usually know too much and print too little. Athletes steadfastly refuse to grasp the reason for the existence of journalists. Together, they resemble two groups of spoiled brats.

“I don’t appreciate people writing stuff without knowing the whole story. They wrote I going 75 miles an hour with no facts, no proof, I never got a speeding ticket. Then they wrote I had the gun in plain view, and that really pissed me off. They invented that. I said I did wrong by not having a gun permit in New Jersey and that was it. What else could I say?”

The city gasped. Barkley has a gun? Oh no! Another head case, another tragedy in the making. The image of this powerful power forward with a hair-trigger temper racing his new Porsche down the Atlantic City Expressway with a semi-automatic 9 mm riding shotgun was too gonzo for even the most professional of journalists to tone down. Stories were sketchy and frantic. BARKLEY BUSTED barked the Daily News front page.

Would Charles use the pistol? “I would never want to kill anyone, but I would never let anyone hurt me. I feel I can handle myself without a gun, but most people would be intimidated by me and they might use a weapon. I’ve had guns for years, but nobody ever knew it. It’s not as if I pull a gun every time I lose my temper or get into an argument. And I never went hunting or anything like that. I usually keep my gun at home. I practice at a range in South Philly, and I’m getting pretty good.”

“If I go on a road trip, I always carry it. Just in case—you never know. People out there are crazy. I always carry a gun since I left college. Everybody has that right as long as they abide by all the laws. I think everybody on our team has a gun. There’s a lot of racism, and people are envious, and we go to bars and restaurants late at night, after games, and you never know. I get tested more than most because I’m big and I’m known and I play aggressive basketball. At a club, let’s say, guys are drinking and they wonder if I’m as tough as I appear. I’ve had problems like that, a lot of problems. Everyone uses me to impress their girlfriends or their buddies. You meet some Serious Knuckleheads Out There.”

Charles Barkley changes his phone number every three weeks. And he still gets harassing calls, macabre messages at all hours. And he gets ghoulish death-threats by mail at hideously dependable intervals. Charles Barkley is scared. A lot of the time. The easiest part of playing basketball is playing basketball.

A few months later, Barkley’s attorney says they should get there early, before the cameras and the reporters set up shop. It’s too late. The Atlantic City County Superior Court is filthy with media. The attorney whisks his client back down the steps and into his car and they drive around the block a few times. His client is all dressed up in a suit and tie. He looks like a grown-up. Possession of a deadly weapon requires a grown-up defense.

When they pass an elementary school, the client asks the attorney to stop the car and let him out. It’s recess time and the schoolyard, filled with kids running and screaming and playing ball, beckons loudly. The attorney thinks it’s a bad idea on several counts.

“This is important to me, Mr. Kaplan,” says the client.

“Stop calling me Mr. Kaplan,” says the former prosecutor and judge. “Call me Don or Donald, will you?”

“I’m just a poor boy from Alabama, and if my mama ever heard me call you anything other than Mr. Kaplan, she’d smack me silly. I gotta get out the car, right here, Mr. Kaplan.”

The client climbs out of the car, removes his suit jacket, folds it neatly on the shotgun seat, and walks into the schoolyard like Gulliver landing on Lilliput. He is instantly surrounded by seven- and eight-year-olds. They throw him a basketball and he starts shooting. His tie gets in the way. He stashes it between two buttons of his white shirt. The kids are giddy. They swarm the client and touch his suit pants and his expensive shirt. He can’t help but look down at them all and smile broadly. He knows this place. It is a safe place. These small people harbor no grudges, demand no promises be kept. They will not judge him harshly when he acts childishly. They want only to be like him. If they only knew how much he wanted to be like them.

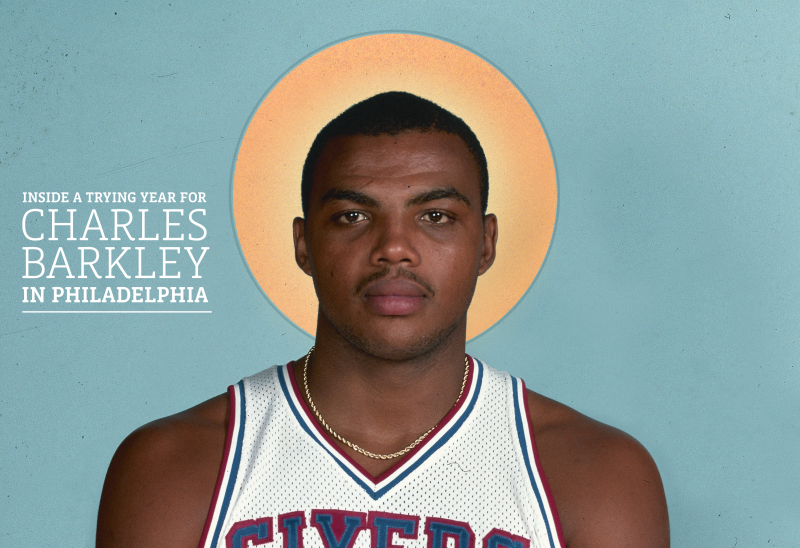

[Featured Illustration: Sam Woolley]