Garry Shandling is worrying a piece of plain chicken (no skin, no sauce, no guilt) with a plastic fork. The tines quiver with indecision (eat? talk? eat and talk and risk having a meteor of thigh meat land on those dry-cleaned jeans … shit! There it goes). He is sitting in his generic office on the CBS lot in Studio City (motel-room art, no personal items, no fingerprints—no clues!), in L.A., alternately taking off his violet sunglasses and peering through his clear tortoise specs.

“Gee, maybe I should put in my contacts.”

He looks squinty and pained, not unlike his HBO alter ego, talk-show host Larry Sanders, bumping into a lower-tier celeb he never invites on his show.

“I’m so confused, I’ll probably start asking you the questions.”

Having banished the chicken to the other side of the room, he has begun poking at a baked potato—plain—but abandons it after a short skirmish. It seems an appropriate time to try to momentarily still this fretful man—a 47-year-old actor/comic/writer currently responsible for The Larry Sanders Show, the funniest, best-written sitcom on television—with a question requiring thoughtful perspective.

Think back: Do you suppose there was ever another point in the history of man when angst, insecurity and primal fear were actually primo job qualifications?

“You mean apart from the job of world leader?”

Finally, he’s laughing. Come to think of it, maybe roaring paranoia was part of the job description of any pre-glasnost big shot. Shandling says he still feels as if the red phone is ringing before every performance. “I would say Halloween’s my favorite night,” he ventures. “I would say that, without fear, something’s probably not going right creatively. I’m usually panicked before going onstage, afraid of failing. The battle is to have the courage to fail.”

Fear will stalk all my conversations with Shandling. And human dread—pulled as slow and sweet as poisoned taffy—is the mainstay of The Larry Sanders Show, a mirror-crack’d parody of the late-night talk show. Print ads promoting the ’96–’97 season featured a Hellraiser view of the top of Shandling’s head bristling with red-tipped acupuncture needles. And this year’s much awaited run didn’t start until two months after the network sitcoms had soared, sunk and otherwise sorted themselves out.

Larry Sanders runs a talk show so ratings-craven it won’t book Nelson Mandela (“He’s truly a great man, but he can’t do panel for shit”). The season opener featured double-barreled paranoia: Larry’s afraid the network is “doing what they did to Johnny [Carson],” giving his guest host all the heavy talent bookings with an eye toward easing old Lar into the paddock. Larry’s also worried that X-Files star David Duchovny is gay and hot for him.

Dissect almost any Sanders plot and insecurity spurts like arterial blood. There are also lively tributaries of sorrow, lust, love, metaphysical questing, sports-car envy. No other mere sitcom speaks to so many levels of the game. If Seinfeld is, in the words of its own characters, about “nothing,” Larry Sanders aspires to be no less than a 22-minute lab exercise on the human condition. Larry; his second banana, Hank “Hey, Now” Kingsley (Jeffrey Tambor); his wily, battle-scarred producer, Artie (Rip Torn); the paranoid Buddhist head writer, Phil (Wallace Langham); and the mordant talent booker, Paula (Janeane Garofalo, an intermittent player this season), interact in a roiling petri dish of human behavior. Meanwhile, real stars (David Letterman, Roseanne, Chevy Chase, Sting, Elvis Costello) show up, often to lampoon themselves. The Sanders green room has become Hollywood’s hippest hangout. Buzz-savvy agents urge clients to step up and take a custard pie to the well-burnished ego.

“When I first thought of the idea,” Shandling explains, “I knew I understood talk shows. I was concerned about whether I could reflect on human behavior the way I wanted to—not just talk about talk shows.” He frowns. “Am I making any point at all?”

Certainly, it’s chewy fin de siècle fare. Shandling’s comic success counts on the understanding that we’ve reached an age of towering trepidation, a post-Chernobyl, retrieved-memory, factory-recall nightmare of Things That Can Possibly Go Wrong. “I happen to think that fear is an overriding human emotion right now in our society,” says Shandling seriously. “So I think it’s an overriding force in comedy and drama. It probably has been for eons. But I think that now people are lost and fearful of what we are going to become—and whether we will fulfill our potential as human beings.”

He sighs and stares out the window.

“Then, of course, there’s fear of cancellation.”

Which, of course, is a joke. It is widely understood that the five-year run of Larry Sanders is solely a function of Shandling’s interest and staying power. He cites personal burnout for the end of his ’80s comedy series, It’s Garry Shandling’s Show, on Showtime. Long before Seinfeldisms were being stamped on greeting cards, Shandling’s quirky little sitcom featured a neurotic comic, his single-guy apartment, and his friends.

Larry Sanders has acquired a much higher profile, largely by virtue of its fearless writing. Scripts have had a canny prescience regarding network machinations (the Leno-Letterman wars, the late-night return of Tom Snyder). And with guerrilla timing, Shandling talked Ellen DeGeneres into burlesquing the media obsession with her sexual preference this season, even as Maalox-foaming network types were parrying inquiries about whether her ABC sitcom character will come out as a lesbian—next season.

This take-no-prisoners stance has shot Shandling from the respected-if-unseen margins to the much-talked-about edge. TV critics greeted his return for the new season this past November with hosannas befitting a small-screen messiah. “Our long national nightmare is over. The Larry Sanders Show is back,” proclaimed Entertainment Weekly. When the show won four Cable Aces in November, Shandling thanked the psychiatric team at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center. The good doctors have also been responsible for the brace of previous Aces and dozens of Emmy nominations (and one statue, to Tom).

Strange, then, for such a winner to act so … incognito. The Sanders soundstage is within pacing distance of the busy barns housing Seinfeld, The Single Guy, and Grace Under Fire, all of which sport logos the size of Chevy Suburbans. The only sign identifying the Shandling bunker is a foot-long plaque that simply reads EDITORIAL ONE (at the star’s insistence). When I tell him that the offices and stages of the talk-show set look far more lived-in than his real office suite, he looks genuinely startled.

“Wow, you’re right. I mean, I never … That’s an interesting observation.”

The only marginally funky niche in this cool beige warren is the writers’ room, a.k.a. the bull pen, an overwhelmingly male preserve redolent of take-out food, aftershave, creative flopsweat, and stale coffee. Shandling, who spent his formative showbiz years in the muggy Naugahyde writers’ lounges of Sanford and Son and Welcome Back, Kotter, says he prefers it to his own sunny office, which, on this tar-melting L.A. afternoon, is giving him the shivers.

“Don’t you think it’s cold? Probably it’s just me.” The cover of the thermostat flies off as he investigates. “SHIT! Kelly? Kelll?” Shandling’s resilient personal assistant, Kelly Grant, materializes to tussle with the hardware. John Ziffren, the show’s producer, walks in and notices the barely touched lunch.

“Garry didn’t eat? Did you do that to him, Ms. GQ? Hey, Garry, you should eat. We’re shooting next week.”

They trail off toward a script meeting—Shandling is forever drifting away to “give a few notes” on dialogue, casting, a story idea. Life grows in story arcs here. And Shandling’s conversation, cadged between obligations, will be episodic at best.

No, he’s not Larry Sanders (or vice versa), friends swear. They probably have the same barber, they may even have dated some of the same women, but Garry Shandling never let his shrink help book talent. And he never had a sizzling thing with Roseanne. What’s similar? They’re both harder to pin down than a summer-replacement sitcom. Poll Shandling’s friends and coworkers and they come up with adjectives like “clear,” “deep,” “generous,” “totally in the moment” and “focused,” fuzzy shrinkspeak that covers everything but defines little. One thing they all agree on: He has the attention span of a fruit fly on bennies. Ten minutes, tops, is the best one can hope for. “I do wander off the set,” he confesses. “Occasionally, a director will come running and grab me. I’m sure I would be fired if it were not my show.”

Daily, Kelly Grant tracks her boss with the same alarmed intensity needed to map the path of an errant SCUD missile. Much of the time, she is doing this via cell phone: “Okay, he’s seven minutes away; he’s on the road. No, wait. I see him on the walkway. Someone get him. GARRY! GARRY?”

Shandling has ducked into the men’s room again. Sanctuary. Much like Larry’s no-nonsense assistant, Beverly (Penny Johnson), Grant must remain vigilant beside her trilling phone, with a fistful of message slips, no-fat menus, and shrink-appointment schedules.

Those who love him have learned to cope with the dips and dodges. Rip Torn, who swears he has never had a happier run than his five years as Artie, says that despite the great affection between them, he couldn’t get the boss to give him a straight answer on the show’s future—and his livelihood. He cites an incident last winter, at the premiere of a Sharon Stone film. Stone had seated Shandling and Torn together, figuring they’d want to talk after a long hiatus. But it got, uh, uncomfortable.

“At the time,” says Torn, “we didn’t know whether we’d have another season or not. I said, ‘Garry, there’s a rumor that the show will start in April or October.’ And he said, ‘That’s what I’ve heard.’ I said, ‘Well, I hate to press it, but I hear you’ve made your decision. What’s the answer gonna be?’”

Shandling stonewalled in a way that would have made Artie proud: “Uhhh. I’ll let you know in a week.”

All this stuff about Shandling’s awesome angst may make for punchy press and award-winning scripts, but Torn says he has his own more accurate nickname for this self-defined Hapless Harry: “I call him Tucson Tough. He’s not the character he plays. This is a very tough guy who runs a very sharp show.”

Just for the record, here are some things that Garry Shandling has not been afraid of:

- Turning down $5 million a year to take over Dave’s old talk-show spot on NBC.

- Turning down more millions from CBS for a show following Dave’s.

- Going to that scary place beyond the gag. Take the time Hank sat alone on the talk-show set and appealed to God, in a moment of startling anguish, to keep his personal porno tape from reaching the press. “It’s a very uncomfortable scene,” says Jeffrey Tambor. “That’s the attraction of these writers. They go past the laughs to the characters.”

- Scripting shots at Jay and Dave, some of which make it to the air. One that didn’t: When Larry asks Artie if their show beat Leno in the ratings, his producer brays, “Sir, we kicked that big-jawed grease monkey’s ass but good. And that gap-toothed fucker….”

“I’m a spitball on the wall. That’s my career. I’ll be moving from cable to ham radio.”

During a conversational lull, Shandling will often indulge in a spasm of self-loathing, a tic rampant in the ranks of post-Woody Allen comics from Richard Lewis to Steven Wright. Janeane Garofalo (whose own company is called I Hate Myself Productions) has said of Shandling, “He’s so full of sheer self-hatred, it’s a pleasure to work with him.”

The old masters shpritzed outward: Richard Pryor at racism, Mort Sahl at politics, Lenny Bruce at repression and censorship, Don Rickles at anybody. But after the disappointments and philosophical fizzles of the ’60s, it may have seemed like so much pissin’ in the wind. When the smoke and incense cleared, nothing much had changed. And in the comedy clubs, there arose a new drug of choice, born of the Me Decade: drinking one’s own bile. Le misérable—c’est moi! Onstage it proved the magic emetic for Shandling, who coughed up tales of his clueless dating games, his despair over his inflated lips and shredded-wheat hair. He made Johnny Carson wince with the excruciating details of his romantic and sexual disasters.

Just how is it that a much loved little boychick raised comfortably in Tucson came so naturally, so willingly to public self-flagellation? What could have roared out of the desert across the street to scare him so badly?

He insists it wasn’t his brother’s death from cystic fibrosis, when Shandling was 10. That was sad, but it didn’t make him fear he was going to die. And it wasn’t his decision to drop out of the electrical-engineering program at the University of Arizona at 22, drive to Los Angeles (“where I didn’t know a soul”) and rent the first apartment he saw. Nor was it the horrific car wreck, in 1977, resulting in a hospital stay of several weeks and affording him the near-death experience that prompted him to quit writing Sweathog jokes for Gabe Kaplan and find himself as a stand-up.

No, it was the night when he was seeking self-knowledge in a comedy dive, circa 1:00 a.m., when the two dozen audience members—all of them drunk—were busy pulling the wings off a buzzy little comic pinned in the spotlight. Shandling climbed onto the stage, grabbed the mike and bellowed, “HOW DARE YOU TREAT THIS PERSON THIS WAY?”

Even then he had a thing about … jeez, human decency. He waded into the smoky outback, visited each table and traded venom until shock struck them silent. “It was like that guy who would spin the plates on Ed Sullivan,” he recalls. “The second you’d deal with one heckler, another would start talking, until they were yelling at each other.” He took a breath and went deep blue: “I got very, very filthy. I found that the core of the audience was really a very dark, dirty place. And then I did fine.”

Which is to say he was as wretched as he dared to be.

“When I worked at The Comedy Store in the Valley, I’d come home so battered from a heckler or a bad show that at two in the morning I’d pull into the driveway of the house I was renting and I couldn’t get out of the car. I’d be so defeated that I would sit in the car for 20 minutes and think, What am I doing? Why am I putting myself through this? It was that painful.”

Somehow, our comic Jonah emerged from the belly of the beast—in fact, was spit out on prime beachfront: Carson spots. He found himself opening for Doc Severinsen in the big Vegas rooms, then winning that coveted showbiz oxymoron, the spot as Johnny’s permanent guest host. Despite this progression, it was no big surprise to Brad Grey, Shandling’s manager and the show’s co-executive producer, when his longtime client turned down the talk-show bids. Even during those heady negotiations, when the two gleefully conspired by phone two dozen times a day, they both knew he’d never assume the bullshit burdens of Johnny. Says Grey, “He knew he wasn’t going to be happy getting in the car every day, driving in, talking to three or four people he’d never speak to if the camera wasn’t on.”

This may be why we’ve read reports lately of a pressured Letterman flushing his socks down the toilet in a fit of pique—something a Sanders script makes great comic hay of. While Dave’s goofy grin has recently approached the smile of rictus, Shandling has found himself some healthier and, hopefully, profitable outlets from the soundstage grind. Sanders episodes referring to the star’s upcoming memoir, Confessions of a Talk Show Host: The Larry Sanders Story, will promote an actual book, to be published by Simon &. Schuster this spring. And Shandling, who has had small film parts in Love Affair and The Night We Never Met, has cowritten his first feature, due to begin shooting this July. It’s about an alien who comes to Earth to impregnate a woman but, things being what they are here, ends up having to marry her. Guess who will play the spaceman who can’t score?

“It’ll probably bomb,” says Shandling, “effectively ending my career.”

But never mind. He has no regrets about roads not taken through showbiz. And he would like this understood: Should the Big One bury Brentwood and rattle his back fillings straight through that tormented cerebrum this very night, he will close his eyes a satisfied man: “I’m genuinely proud that I’ve been honest with myself. I’ve been able to commit to growing as a person and within my career and will continue to do it while maintaining a decent sense of ethics and morals.”

From a guy with more defenses than Garry Kasparov, Shandling’s musings about human fulfillment can sound as earnest and jejune as The Tao of Pooh. But he is a seeker, and that’s no send-up. He reads Zen books and meditates in the woods. Says when he’s not working he can empty his mind as easily as a bag of Doritos. If Larry Sanders had a problem with Percocets in one season’s finale, Shandling’s darkest little secret, his hitherto unreported habit, is his growing stash of self-help books. The same man who expends countless brain cells on pussy jokes is bullish on Deepak Chopra. “But I stop short of The Celestine Prophecy. I want that made clear!”

In fact, here is Shandling at his desk, signing small gift cards to send out with copies of Everyday Zen: Love & Work. It’s about how to be in the moment, free of fear—floating far above the Nielsens. “I’m going to give you this book,” he says. “And then you can write that I gave it to you.”

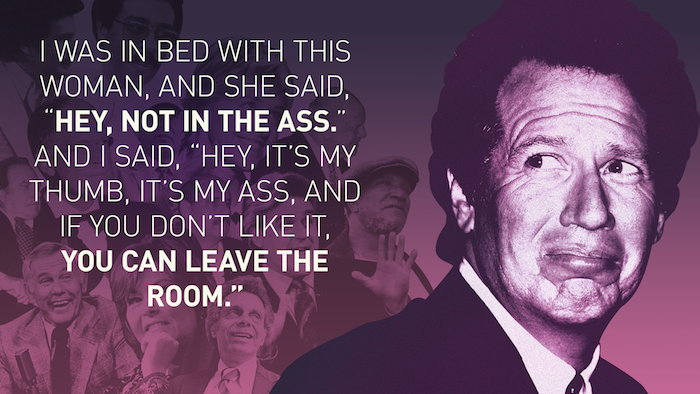

Penis. Ass. When things get too scary or boring, he grabs for them. “I have to tell you,” Shandling confesses, “there’s nothing funnier to me than a good penis or a good ass joke.” He knows it might be unhealthy performed in excess, but he just can’t stop himself. “I write a lot of penis and ass jokes, and I do them all day long in the writers’ room, on the stage in rehearsal.” He’s got dozens, but here are some favorites:

I was in bed with this woman, and she said, “Hey, not in the ass.” And I said, “Hey, it’s my thumb, it’s my ass, and if you don’t like it, you can leave the room.”

He says they’re “very organic” to him and close to his personality. By his kinks, ye shall know him: My dog’s penis tastes bitter. I don’t know if it’s his diet.

He’s genuinely proud of his pecker oeuvre. “It must have something to do with the little-boy quality,” he offers, “saying, ‘Look, look, I can be dirty.’”

He’s just a nice, considerate guy who needs a hit of tastelessness the way some folks need Prozac. For this reason, he says, he never allows journalists in the writers’ room, where he is wont to blurt free-floating filth and gross insult with the untrammeled verve of a Tourette’s patient. Shandling insists his sewer dives are not mean-spirited, just necessary. “The key to my writing personality is that I do believe in a certain amount of inappropriateness. It’s an essential element of getting my fire going.”

Bob Saget has known Shandling since their stand-up days in the early ‘80s—well enough to ask Shandling to be a pallbearer when his sister died, three years ago. You want inappropriate? Shandling rated Saget’s eulogy. “He only gave me a nine out of ten,” carps Saget. “I said, ‘Can’t I get the extra point because she’s dead? Just grade on the curve here.’”

On the set, Garry as Larry is staring into his desk drawer with that bring-me-an-airsickness-bag grimace.

“Artie, there are tampons in my desk drawer.”

Rip Torn, as Artie, leaps up and reaches in for the offending items. The other actors are dressed for rehearsal: jeans, T-shirts, Air Jordans. Torn is in a rumpled but well-cut pinstripe suit, an open-collar white shirt (also rumpled) and a ball cap. Even with a fistful of Tampax Supers, he has the air of a man in command.

Artie is the show’s towering creation, a veteran producer with a heart of gold and battery acid in his veins. He snaps network logic over the dithery, emotional plaints of the “talent,” listens to nervous breakdowns—but only during the 60-second breaks. With sangfroid and coruscating humor, he has gotten Larry through a ratings slump, a paternity suit, and the deep trauma of not being able to perform in bed with Sharon Stone (“I warned you, didn’t I? If you’re in a show business relationship and the woman is more famous than you are, she’s the one with the dick”).

Right now—the tampons having been claimed by Larry’s assistant, Beverly—Artie, Larry and head writer Phil are discussing a woman writer with whom they’ve just had a meeting. Larry wants to hire her. Phil whines that she’s from Harvard, so she must be arrogant.

ARTIE: And where’d you go to college, Phil, my boy?

PHIL: Chico State.

LARRY: Great welding school!

ARTIE: Just remember, Phil, those Harvard grads wipe their asses with the same hand you do.

Shandling dissolves at Tom’s cheerily scabrous delivery. Even Artie’s dead-perfect Windsor knots can’t keep the profanity from welling up and out. He is, says Torn, “a barbarian in an impeccable suit,” a hard-charging, hemorrhoidal totem for the showbiz hypocrisy always at the center of Shandling’s comic crosshairs. Artie takes his élan and his Savile Row tailoring from Johnny Carson’s longtime producer, Fred DeCordova, who’s been on the show. But, says Torn, he also represents a long line of Hollywood thuggery, from Louis B. Mayer to the manicured but black-belted Michael Ovitz. Asked how he’d rate his current boss in that continuum, Torn doffs his ball cap.

“I’ve only heard Garry yell once in five seasons,” he says. “Hell, he wanted his food, and it wasn’t there. Our modus operandi around here—and we learned it from Garry—is, Don’t get mad—get funny!”

A day later, Shandling is smiling. Great news! He’s just gotten the green light from Ellen DeGeneres to do the is-she-or-isn’t-she? show.

It’s an episode Shandling says he very much wanted to do, revolted and spooked as he is by the current rapacious demands of enquiring minds: “What this show explores is how different that work face is from the real person. And does everyone have the right to know the real person?”

If the show’s damning portraits of pushy TV Guide and Entertainment Weekly reporters are any indication, Shandling doesn’t think so. And he’s equally unforgiving of celebrity faux pas as he sends his characters into tabloid hell. Larry has already suffered a paternity suit (somehow it mushroomed from an ill-advised blow job in a fast-food parking lot). Last season’s drug intervention, chaired by Roseanne, was a touching, if twisted, love-in, as staffers spoke up about the boss’s bad behavior. (Said Hank’s then assistant, Darlene, “It really hurt me when you called Hank a fat shit.” Corrected Artie, “No, Darlene, it was a ‘talentless fat fuck.’”)

Real life isn’t as breezily scripted. When Shandling’s live-in girlfriend, Linda Doucett (who played Darlene for three seasons), posed for Playboy, a parallel bit was written into the show. But no one in the Shandling camp played it for laughs when Doucett sued Shandling for sexual harassment, charging that her employment was terminated when their relationship ended. Artie might have crafted the statement Shandling issued (“We are saddened by the false and outrageous charges…”).

“Do you mind? This is my place. I’ve got to sit in the sun. I’ve always needed the sun.”

We are outdoors on a far corner of the CBS lot, and we are huffing a large cast-iron park bench into direct afternoon sun. Shandling has one of those slightly parboiled complexions that bespeak a lifelong habit of sun worship. Beneath the thuk-thuk of a traffic copter, we settle in for a few uninterrupted minutes on life and love. Head back, eyes closed, Shandling conjures the teenage trauma that has probably, in his estimation, doomed him to an old age of eating Häagen-Dazs in bed with his dogs—a Border collie and a spaniel.

“In sophomore year, in social-dance class, they had a line of girls on one side of the room, boys across from them. And they brought the lines together, and whoever was your match you had to dance with. I remember my girl looking at me and rolling her eyes. It’s an image I’ve never forgotten.” Beat. “I think my mother gave me that same look when I was born.”

Now he’s warming up, sounding a lot like a guy who based his early career on his inability to score. He admits to a teenage worship of Woody Allen, the loser who set the standard for three decades of lonely-guy incarnations.

Shandling continues, “I’m proud to say I’ve evolved to the point where I roll my eyes. It gives me the feeling I’ve matured as a man.”

Come on, Gar. It was one thing being the hapless bachelor living in the tiny Culver City rental, cranking out different ways for Redd Foxx to clutch his heart and bellow, “I’m coming, Elizabeth!” It’s another to be a famous, successful single guy who has finally grown into his face and hires pricey stylists to have at that hair. Hell, even Jon Lovitz gets chicks.

“I don’t think of myself as a celebrity bachelor at all,” Shandling says. “Just sort of a semi-hapless bachelor. It’s difficult for me to find someone I’m interested in as much as it’s difficult to find someone interested in me. The chances of those things crisscrossing? I can’t imagine it happening.”

He says he’s not looking for a big relationship; his deepest and most intense commitments revolve almost entirely around work. “I probably should get more of a social life,” he grumbles.

“I think that Garry lives a little like he’s on the lam.” This from Sharon Stone, who has known Shandling since the early ‘80s, when they were both students of the late acting coach Roy London, who nudged them into scary pits of creative discomfort. Sharon wanted the big parts; Garry warned the big break. “We’d work out jokes together in the living room,” Stone recalls. “We’d sit there laughing—is this one good? Does it work? Then I’d stay up and watch it on Johnny. It was really exciting.”

Yes, she says, he was very scared then. And she agrees with Shandling’s take on the fear factor in performance: “You have to be greatly afraid. It’s the confrontation that makes it work.” Laughing, she adds, “Though I think with Garry, it might be all fear.”

Final phone conversation, rescheduled only twice. We’re talking about women again. Although most of his friends are guys, Shandling says he has learned to have some good female friends as he’s gotten older. But women can still scare him to death. I mention that all the women on Larry’s show seem to have his number, and he sighs deeply.

“I feel that women have their way with me. And to a large degree, I’m a victim to women and their wiles.”

He drifts off, carrying on a conversation in his office, apologizing, back, then gone again. Fear! Were we talking about fear again? Well, yes. I have been reading his Zen book and came to a chapter on “The Bottleneck of Fear.” The author, a respected Zen instructor, insists that “the person who says, ‘If you knew what my life has been like, it’s no wonder I’m such a mess—I’m so conditioned by fear, it’s hopeless,’ isn’t grasping the real problem.”

Doesn’t the whine of this fearful apologist sound like the weekly cant of Larry?

“I wouldn’t say it’s the overwhelming drive within me, but I certainly think that I possess a normal amount of human fear,” says Shandling. “I do have a fear of embarrassing myself that started in high school.”

He says he still takes his fears to the shrink. After all these years, he never bores himself on the couch, and he occasionally leaves a session with some usable jokes. The rest of the random jitters he knocks out past the klieg lights, and into the dark:

I told my doctor my penis was burning. He said someone must be talking about me.

[Featured image: Sam Woolley/GMG]