They were drinking their dinner in a joint outside Chicago. It was just Mike Royko and his pal, Big Shack, and whatever their bleary musings happened to be that night three years ago. They probably never even gave a thought to the fact that they were in Niles, Illinois, which qualifies as a suburb and therefore should have been treated by Royko as if it were jock itch. But Niles is where a lot of the Milwaukee Avenue Poles he grew up with fled when they started finding themselves living next door to neighbors named Willie and Jose. So this was shot-and-a-beer territory after all. The only thing it lacked was a do not disturb sign.

“Hey, you’re Mike Royko!”

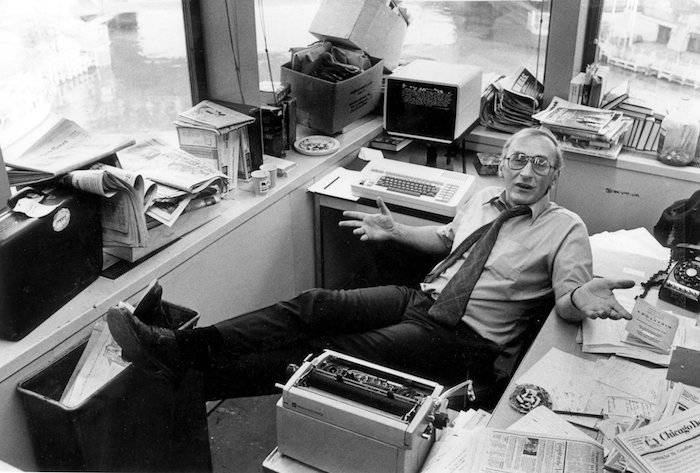

It happens to him all the time even though newspaper guys are supposed to be bylines, not recognizable faces with bald heads, crooked smiles and ski-jump noses. How Royko, who is a baggy-pants character no matter what he wears, cracked the celebrity lineup is no mystery, though. Nor is it a tribute to the tiny picture of him that has decorated his column in each of the three Chicago papers he has worked for. The secret is words. The words that in 1971 paid off with a Pulitzer Prize for his newspaper commentary and a best-selling book called Boss, in which he dissected Mayor Richard J. Daley. The words that now appear, via syndication, in the Los Angeles Times, the New York Daily News, and 223 other papers. The words that always have originated in his hometown, Chicago, five times a week, year after year after year.

“I’ve read you all my life.”

Royko’s admirer was male, white, crowding 40, with a pretty wife who quickly made it known that she was a more voracious reader than her husband. Soon the three of them were so wrapped up in one another that they failed to notice Big Shack, all 220 pounds of him, lumber off to the can. But Big Shack is important to this story, first, because he is the source of it, and second, because he returned just in time to save Royko.

“The guy was choking Mike,” Big Shack says. “I guess his wife had gotten a little too friendly, and Mike, well, you know Mike. So there I was, peeling the guy’s fingers off Mike’s throat one at a time.”

Big Shack can laugh about it now.

“What can I tell you? In ten minutes Mike went from hero to bad guy.”

It wasn’t his maiden voyage.

He jumped to the Chicago Tribune last year, and there was such a stir in town that you would have thought Carl Sandburg had come back to life, strumming his guitar the way he used to in the city room of the old Daily News.

Royko wasn’t a Tribune guy. Since the first day he called himself a columnist he had been making fun of the dowager that once billed itself as “The World’s Greatest Newspaper.” He liked to count the harrumphs of its pompous editors and wonder if there was a heaven for its late publisher, Colonel Robert R. McCormick, who was, in the backhanded estimation of one critic, “the finest mind of the twelfth century.” The Trib was where they put a full-color editorial cartoon on the front page as late as 1970 and where Genghis Khan could have hired on as a political pundit if he had been around to apply for the job.

Even when the paper finally conceded that archconservatism wasn’t necessarily the truth nor cluttered pages the light, it remained a bastion of smugness and complacency. “I’ll never work there,” Mike Royko said. Again and again and again. But Rupert Murdoch, the Australian press baron who made his fortune in tabloids, forced him to go back on his word.

Murdoch forked over $100 million for the Chicago Sun-Times last year and, in the words of an editorial writer who fled, “sodomized it.” Royko, for six years the paper’s linchpin and lifeblood, was gone before he had to say ouch, though it took a court ruling to release him from a $300,000-a-year contract forged with the Sun-Times’ previous ownership. No sooner was he safely at the Trib, however, than his name was taken in vain by those he left behind.

They didn’t want to hear Studs Terkel, Mike’s friend and the nation’s foremost oral historian, tell them that “the Tribune was the lesser of two evils.” They watched Royko plead his case against the intruder he called “the Alien” on every TV newscast in town; they heard him warn Phil Donahue’s dewy-eyed female audience that “no self-respecting fish” would be wrapped in a Murdoch rag; and, though the name-calling was priceless, they felt cheapened as a result.

“Mike was getting out while the rest of us were stuck,” says a reporter who worked with Royko at both the Sun-Times and Daily News. “All he cared about was himself. Everybody else could go shit in their hats. I’ll tell you one thing: He used to be my hero, but he isn’t anymore.”

Royko says he doesn’t care. He might even be telling the truth. He mutters that he would have gone on strike with the newspaper guild at the Sun-Times long before Murdoch bought it, but the guild members, for their part, would never have sacrificed one day’s pay to get him a fatter contract. “Ah, what the hell,” he says at last, and orders another Lite beer—“Nah, make it a Beck’s this time”—and lights another Pall Mall.

It was a different business when he started. Probably a better one, too. Never mind that the Tribune props him up like a Ming vase now. If he were 22 instead of 52 and he walked in the door with the credentials he had at the beginning, the fat cats there would send him packing. As a matter of fact, that’s exactly what happened back then. And there were repeat performances at the Sun-Times and Hearst’s American. But the Daily News, where numerous Pulitzer Prizes decorated the newsroom and foreign correspondents weren’t begrudged their trench coats, hired Royko anyway in 1959. Nobody seemed to care that he was a high-school dropout who only later got a diploma and acquired his world view as an usher at the Chicago Theater and a stockboy at Marshall Field’s department store. He could do a job; that was all that mattered. He had been a reporter on a chain of weeklies in the city and had served honorably at the City News Bureau, long the proving grounds for Chicago newspapermen, and he was ready.

“What the fuck did anybody at those other places know?” Royko says. “I doubt if they’d ever read The Man Who Laughs by Victor Hugo.”

Royko had.

That quiet commitment to culture was part of the edge he had always nurtured. The rest sprang from the inspired craziness that his colleagues on the Daily News’ four-to-midnight shift weren’t sure would transfer to the printed page. They laughed when Royko would leave the story he was writing to climb atop a desk and do his impression of a love affair between Eleanor Roosevelt and Adlai Stevenson, but characters were hardly a rarity at the News. The inmates there had seen editors armed with copy spikes chase one another around a desk and a horse-racing writer lying naked on the managing editor’s desk so he could get a rubdown from the masseur he had steered to a winner. In neither case, unfortunately, did goofiness lead to greatness.

But Royko started proving he was different as soon as the News turned him loose in 1962 on a once-a-week column from his beat at the County Building. “They were giving a lot of people columns back then,” says Charles Nicodemus, who was the paper’s whiz-kid political reporter, “but Mike’s was the only one that survived.”

The joke about column writing is that it’s like be married to a nymphomaniac: As soon as you’re finished, you’ve got to start over again.

There were two reasons: hard work and insecurity. “When I got the column, I used to labor and sweat, just drive myself nuts twelve or fourteen hours a day,” Royko says. “If something only took me four hours to do, I knew it wasn’t any good.” He would write pieces, then tuck them in his desk the way he did his Christmas column about a modem-day Mary and Joseph who get cold-shouldered everywhere they turn. “I started working on that one in ‘63 and I didn’t let go of it until ‘67,” he says, “and the thing became a nickel-and-dime classic.”

“Classic” is a description that gets tossed around regularly about Royko’s work, and not just by the man himself. It is entirely possible that no one has worked the Monday-through-Friday column grind any better than Royko, and certainly no one has worked it any longer. The joke about column writing is that it’s like being married to a nymphomaniac: As soon as you’re finished, you’ve got to start over again. And you can sense the weariness in Royko when he says he would like to walk away from it all and try to write a comic novel. It wouldn’t be easy, though. “He needs to be Mike Royko,” says John Sciackitano, the Sun-Times graphics expert who is also known as Big Shack, “and Mike Royko writes five columns a week.”

He has written them sick, tired, and hung over; he didn’t miss a day when his father died last fall. Whatever the circumstances, whatever his condition, he has dug into all subjects and followed only one law, his own: Never be boring. He has written memorably of Chicago’s unmarked-bills style of justice: “One day a waitress reached to pick up what she thought was a remarkably large tip. A judge gave her a karate chop on the wrist.” And of the insanity of holy wars: “I never believed any of those stories going around a few years ago that ‘God is dead.’ How could (He) be? We don’t have one weapon that can shoot that far.” And of his alter ego Slats Grobnik’s problems with liberated women: “Why should I waste the price of a movie and a hamburger on a girl who don’t know the meaning of the word ‘okay’? If I wanna be around someone like that, I’ll go to a church and talk to a nun. It’s cheaper.”

Royko has confounded liberals by advocating capital punishment and infuriated conservatives by making sport of Ronald Reagan’s sleeping habits. He has done for Chicago what Dickens did for London, and though there are columns he wishes he hadn’t written—“If some truckstop lady with a bouffant hairdo wanted to mourn Elvis Presley, who the hell was I to call her grief tasteless?”—he is shouted down by his admirers.

“I don’t know who the best is—maybe some guy in Peoria,” Royko says. “But day in, day out, you gotta chase me; I ain’t gonna chase anyone.”

Being on top can be a pleasure, as it was the night a summer rainstorm hit an outdoor jazz concert and the city’s aldermen and ward heelers raced to be the first to offer Royko an umbrella. “They’re public servants, right?” he says, smiling evilly.

“Well, it’s like you’re always at the paper. You come in in the morning and you don’t leave until it’s dark, but it really doesn’t seem to take you very long to write once you get started.”

He is also a target, though, and that is the painful part of his celebrity. Wise guys recognize him and call him motherfucker; newspaper people forget how long and hard he labored to keep his beloved Daily News alive. When the News died in 1978, he moved to the Sun-Times, which was in the same building, on the same floor, but miles away from where he had ever wanted to be. He was surrounded by old rivals, reporters and editors of whom he had always thought the worst, and in short order he decided he was right. “They were backbiters, backstabbers, and stoolpigeons,” he says. Now, at the Tribune, he is confronted with timidity; there is at least one editor who is afraid to talk to him, and reporters shrivel up when he looks at the first edition in a newspaper hangout called Billy Goat’s Tavern, sees no Chicago story on page one and roars, “This fucking paper!”

The bravest of the bunch may be the young copy editor who materialized at his side one night toward closing time at the Goat’s. “Mr. Royko,” she said, “may I ask you a question?”

“Sure, kid,” he said.

“Well, it’s like you’re always at the paper. You come in in the morning and you don’t leave until it’s dark, but it really doesn’t seem to take you very long to write once you get started.” She took a deep breath. “What do you do all day?”

There were regulars there that night who actually turned away for fear they would see this foolhardy creature reduced to tears and ashes. But Mike Royko simply took her hand, kissed it and said, “Young lady, all I do all day is my column.”

The kid had a degree from Yale and a father with a Kennedy-clan name. He also got a job with the Daily News at a time when it shouldn’t have been hiring anyone, much less a beginner. But the editor appreciated patrician breeding, so the kid came to work. On his first night he strolled up to the columnist he had long admired from afar.

“Hi, I’m the new kid on the block,” he said, offering his name and a hand to shake.

Royko looked at that hand as if it were diseased.

He uttered not a word, just let it dangle in the air, growing heavier and heavier until the kid finally put it back in his pocket and slunk away, too humiliated to speak.

There are a lot of people Royko doesn’t like, and Yalies with clout fall somewhere between punks who play ghetto blasters on the El and the bleeding hearts who don’t think New York should be blown off the map. Not that he doesn’t need friends. “He can use as many as the next guy—he’s no loner,” Big Shack says. “He just doesn’t allow people to get close to him. Maybe he’s afraid to get hurt. It’s one of those things; ‘I need you, but I don’t need you.’”

Chicago’s amateur statisticians long ago lost count of how many conversations Royko has interrupted or taken over, or both. He has been equally uninhibited in moving in on other men’s dates. “He’s always patting them on the ass,” one Royko watcher says, “or saying, ‘What are you doing with this jerk?’” And he is at his worst when he is drinking.

“He’s a binge drinker,” Big Shack says. “He’s either off or he’s on. When he’s on, he’ll start out with wine, go to martinis, beer, brandy. I’m talking eight, ten hours of drinking. I don’t want to be around him when he drinks,” Big Shack says, “and I love the guy.”

There are those who don’t, of course. There are those who will fight him. “I’ve only had three fights in all the years I’ve been drinking at the Goat’s,” says Royko. But that isn’t what his public wants to hear. Nor does it particularly care that his latest bout—with a Sun-Times editor who used to work at the Trib—was a loss. “He threw a right hand and caught me on the ear,” Royko says. “Then I threw one and caught myself on the ear.” He may have been bruised, but his image wasn’t. To Chicago he was still two-fisted, hard-drinking, cantankerous.

“Even when he’s sober, there’s almost this disdain for people,” Big Shack says. “It doesn’t cost anything to say hi to someone. But I’ve gotten on an elevator with this guy and ridden up four floors and he didn’t even know I was standing next to him. He gets like that; it’s hard to say where he’s at.”

Wherever it is, other people don’t matter, don’t even exist.

“If the Cubs win,” Mike Royko said early in the game, “we’ll dance in the street.”

Judy Arndt didn’t believe him.

She has been Royko’s main squeeze for the last couple of years, an attractive, unpretentious former congressional aide who tolerates his public excesses and revels in the side of him that few other people see. She has watched him play the doting uncle, listened to him wax lyrical about Mozart, kidded him about the glass of buttermilk he drinks every night before bed. These gentle, homey touches hardly ever go on display, nor could Judy imagine tonight would be any exception, even after the Cubs clinched the National League’s Eastern Division championship in Pittsburgh, their first taste of glory in thirty-nine years.

“In Chicago there was always that added color that gave the ladies in the suburbs a little kick, a sexual kick,” Studs Terkel says. “Forget about Sandburg’s big shoulders; this was the city of AI Capone.”

At Billy Goat’s, Royko was on the stool closest to the TV boasting that he had predicted the title and recalling such lovable Cub failures from the past as Boots Merullo and Stout Steve Bilko. He jokingly threatened to punch the only available New Yorker, and he carried on for the wire-service reporters and radio stations that had tracked him down. Then he told Judy, “Let’s get out of here.”

In a little while, delivery trucks would be rumbling past the Goat’s with the first editions of the Trib and Sun-Times, but now the street was sleeping in its own dank grit. The fire hydrant on the corner was leaking, and someone had vomited on the sidewalk. Mike and Judy scarcely noticed.

He took her by the hand and they danced, just the way he had promised they would. Slowly they whirled and dipped to the music only they could hear. They spun round and round, for the Cubs, for themselves, for the good times.

Old man Royko’s saloon was called the Blue Sky Lounge because some beer distributor got fancy. Usually beer distributors favor their clients with free glasses or a cooler, but this one walked in and decided he would cover the ceiling with blue crepe paper held in place by silver stars. The name that followed was a natural.

It was more of the same when Royko’s parents divorced and his mother opened a bar of her own. There was a plastic palm tree stuck in the front window, so she called the joint the Hawaiian Paradise.

Such was the logic that reigned on Chicago’s northwest side as Royko grew up among characters named Chisel and Joe Gorilla and a father who once blasted a hole in Joe’s front door because Joe had shot the Royko family’s dog. “Everybody was probably a little out of kilter,” Royko says. But what did he know? He was just a snot-nosed kid who kept his mouth shut while the grown-ups talked about how FDR was saving the country and why the Cubs couldn’t beat the Cardinals. “There wasn’t any television then,” he says, “but it was sort of a more intelligent version of the Donahue show.”

As soon as Royko was old enough, he was cleaning the Blue Sky bar and opening the side door on Sunday morning so the serious drinkers could have a pop to get them through mass. By 14, he was a bartender whose heroes were the softball players who raced into the bar for a beer between innings. It was his introduction to the world he has passed on to his readers.

“In Chicago there was always that added color that gave the ladies in the suburbs a little kick, a sexual kick,” Studs Terkel says. “Forget about Sandburg’s big shoulders; this was the city of AI Capone.”

What better place for Mike Royko to tangle with that power broker without peer, Richard J. Daley, mayor for more than two decades until his death in 1976? Though Daley was an Irish mug from the south side, where Royko had gone only to drink before he was legal, the two of them had breathed the same vapors, supped at the same trough, thought the same thoughts. Royko realized the similarities when he was writing Boss. Daley refused to be interviewed for the book, but his silence didn’t matter. “Every time I wanted to know why he did something in a certain situation,” Royko says, “I just put myself in his shoes.”

It was a good fit, whether Daley was self-destructing at the 1968 Democratic National Convention or replacing the lean and hungry young men around him with his own sons. Royko can understand more than ever after having to put up with Daley’s pipsqueak successors. All Jane Byrne wanted to do was pad her campaign war chest; all Harold Washington, the city’s first black mayor, has done thus far in his administration is feud with white aldermen who have the nasty dispositions of night-shift cops. So what if Byrne and Washington talk to Royko? Daley never did, he wouldn’t even admit he knew who Royko was, and he was still more fun.

“The afternoon papers were always waiting for him in his car when he went to lunch,” Royko says. “He would always open the Daily News to my column, and if I was zapping someone else, he would cackle with glee. If I was zapping him, he would throw the paper down and be grumpy all through lunch.”

Those were the days.

Sometimes he will stare out the window in his office at the Tribune, with the ribbons of traffic below eventually giving way to Lake Michigan. The smoke from his cigarette will curl around his head and nothing else near him will move, and you will wonder what he sees. Or whom.

She died before her time, at age 44. A cerebral hemorrhage killed his childhood sweetheart, the mother of his two sons, the wife who was always there to offer him shelter from the storm. “Mike was never an angel,” a friend says. But there were some things he could share only with the woman he first knew as Carol Duckman. They were the things the two of them never expected when he was a workaday reporter—a trip to Europe on the SS France, for example, and the summer home they bought in Wisconsin, writing a check on the spot and laughing like kids having their noses tickled by champagne for the first time.

Then, in the fall of 1979, she was gone.

“I couldn’t live with my grief,” Royko says. “I thought I might drink myself to death.”

When he lost his taste for that, he tried to end it all with work. Once again his days stretched to twelve and fourteen hours, lonely séances in the out-of-the-way place where the Sun-Times’ editorial writers dwelled, a place where reporters he never trusted couldn’t watch him suffer.

Five years have passed since then. To the outside world, it seems the tragedy has been put to rest, for there are still Royko columns condemning San Diego as a nest of John Birchers, and there are still stories coming out of Billy Goat’s about the female bottoms he has patted. But Royko knows the truth, and it has nothing to do with appearances.

“You lose a wife, you never really come out of it,” he says. “What happens is, you become different.”

He lights a cigarette and takes a puff.

“I don’t think my life has had a hell of a lot of meaning since Carol’s death. Since she died, I’ve never been sure what the hell I’m about. I could accept dying tomorrow because I don’t think I fill any great importance to anybody. My life has lost its structure.”

The cigarette is forgotten now, left to burn untended.

“I still know who I am. I’ve been who I am for so frigging long. I’m Royko the columnist. When Carol was alive, I was so much more.”

Maybe that’s smoke getting in his eyes.

Postscript:

I’d been in exile for nearly three months when I set out to write about Mike Royko. I put myself there one night at the Sun-Times in June 1984 when I threw one of Rupert Murdoch’s newly imported henchmen over a desk, then picked him up and threw him back where I’d found him. As a way to lose a job, I have to admit it was fairly dramatic, not that drama was on my mind at the time. This half-wit pagan bully, whom I’d never before laid eyes on, thought he could waltz up and insult my work and integrity. He was wrong, but his hang time wasn’t bad.

No sooner did I become an ex-sports columnist at the paper than my marriage fell apart. If I’d been as tough as I thought I was, I would have brushed aside the wreckage and thrown myself into as much freelance work as I could drum up. Instead, it was all I could do to pedal my crappy, one-gear bike up and down Chicago’s North Shore while I wondered if I’d ever get my life unscrambled. The first sign that everything would work out was a phone call from Vic Ziegel, the ultimate press-box mensch, may he rest in peace. He had done a story for GQ, and thought the magazine would be a good fit for me now that it was making room for journalism among its fancy-pants fashion spreads. When I got on the phone with managing editor Eliot Kaplan, he told me he’d read me when he was a kid. Wonderful. I wasn’t 40 yet and I felt like a fossil. But Eliot listened to my story ideas anyway—the emerging Elmore Leonard, the guitar genius Ry Cooder, the mysterious novelist Leonard Gardner—and then he said, “What about Mike Royko?”

It was one of those questions that let a writer know a decision has already been made for him. In this case, I was fine with it. I may have learned more about writing by reading Jimmy Breslin, but for relentless, fearless, often bust-a-gut funny columnizing, no one was better than Royko. On top of that, he had made me feel welcome when I arrived at the Chicago Daily News in 1977, and we had stayed on good terms when the paper folded the next year and we moved to the Sun-Times. We’d never been drinking buddies, though; I can make a glass of wine last all night, and Mike could make a night last an entire weekend when he was hitting it hard. Still, I’d killed a lot of time very enjoyably hanging out in his office. Sometimes he’d shake his head at one of my periodic bouts with bad behavior. “I’m supposed to be the wild man here,” he’d say. Mostly, though, I’d listen to him tell stories like a well-polished favorite about the night he got chased out of a cop bar by one of Chicago’s liquored-up finest, who pulled a gun and blazed away at him as he sped down the street. Apocryphal? Perhaps. Mike always was a great performer.

When I called to ask if he’d sit still for the story, we hadn’t spoken since Murdoch, or, as Royko called the Australian media baron, “The Alien,” bought the paper and Mike jumped to the Tribune. He seemed amused that I was writing for GQ and, without saying so, he made sure I understood that he’d be doing me a favor to let me shadow him. But he loved the spotlight too much not to give me all the time I needed. It was more than impulse, I’m sure, that moved him to dance with his girl friend (and future second wife) outside Billy Goat’s while I happened to be with them. On the other hand, I’ve never doubted the sincerity of his emotions in the story’s final scene. Guys like Royko don’t fake tears.

What surprised me when I re-read the story recently—besides how arcane the idea of star newspaper columnists has become in this age of blogs and Tweets—was his apparent lack of concern about showing his abundant rough edges. You could say he was too big to worry about anything a sportswriter wrote, or maybe the death of his first wife had knocked the caring out of him. I’m sure both those things factored into what he let me see of him. But Mike was complicated in the way that those touched by genius often are. He lived primarily by the rules that served him best. It was no surprise then that there were more Roykos than the one I saw in his office. He could be as bad drunk as he was engaging sober. There was also the Royko who was content to sit at home by the fireplace reading Shakespeare or Nelson Algren, too, but woe to anyone who caught him on a good day and expected him to be the same the next day.

The Royko who surprised me most, however, was the one who really was insecure and cultivated hangers-on who earned the privilege of basking in his reflected glory by laughing at his jokes and never failing to say, “That’s right, Mike.” You’re wrong, however, if you think Big Shack—John Sciackitano—was one of them. He was their exact opposite, a friend who cared only about Royko’s best interests and tried mightily to protect him from himself. Too bad he couldn’t have protected Mike from the hangers-on, too.

Late one boozy night at the Goat’s, someone mentioned a Tribune editor who had just arrived from the New York Times and Royko went into a profane, drunken tirade. The hangers-on gave him an amen while I frantically took notes. The next day an uncharacteristically remorseful Royko called to ask if I’d keep his outburst out of my story. “That was the whiskey talking,” he said. I seriously doubted it, but the last thing I wanted to do was to stir up trouble for him at the Trib when he was still settling in there. This was the thank-you I got: When the story ran in March 1985, I heard from friends in Chicago that the hangers-on were bragging about how they’d leaned on me to keep the anecdote from making it into print. Apparently Mike had told them about calling me, and they were determined to make the most of a rare chance for glory.

I never heard from Royko. I would have been surprised if I had. He had an image to maintain, and besides, his life was changing. His move to the Tribune would be followed by a move to a suburban manse—“Heresy!” cried Chicago’s barstool intelligentsia—and a rightward drift to his column that made him seem old and crotchety. Meanwhile, I spent the next 18 months writing a sports column in Philadelphia before I took refuge in Hollywood and a new career in which I rarely read him. But when a friend called in 2003 to tell me Mike had died, at 64, I felt the same emptiness I had the night the last edition of the Chicago Daily News came off the press. Mike made his name at the News and opened veins to bleed life into it for as long as he could. Now he had run out of time just the way the paper had, and a light had gone out in the business, a light that would never come on again.—John Schulian

[Photo Credit: Chicago Tribune]