For all I know, people have been slipping out of this world in occupational clusters for years. Four journalists, I noticed, passed on one day last year, and their obituaries filled a whole corner of the newspaper. What news, I wondered, had sent them over the edge? Last fall the Daily News ran two columns of obituaries, each ending with a list of celebrity names. It seemed the service industry of Hollywood––hairdressers, caterers, costume designers—had sent out its ghosts in one big blast.

I began to search for patterns. Some days sculptors were called, some days former Brooklyn cops and firemen. It was much more than a coincidence and certainly more than just the wicked wit of an editor on the graveyard shift. It was supernatural.

I remember when I began to use the word supernatural. It was October 25, 1986, the day The New York Times ran side-by-side obituaries for the scientist who isolated vitamin C and the scientist who isolated vitamin K. One was ninety-three, one was ninety-two; one died on a Wednesday, one on a Thursday; one’s obituary ran three columns, one ran two—make something of these differences if you dare. Both men were Nobel Prize winners. One extracted the vitamin from tons of cattle adrenals scooped from the Chicago slaughterhouses (and also from paprika); one extracted female hormones from tons of sow ovaries. Dr. Albert Szent-Gyorgyi and Dr. Edward Adelbert Doisy, Sr., Mr. Vitamin C and Mr. Vitamin K, left the world together.

You never know in which section of the Times the obituaries will appear—after sports? after business? after unpleasant bits of environmental news? At least the Times has mini-biographers on staff, reporters with a good sense of history and a talent for making tons of sow ovaries poignant, and even compelling.

I began to savor the details. I began to clip the columns that memorialize people who might have been paired in life. A member of the Republican National Committee and the founder of the National Federation of Republican Women’s Clubs. A veteran UPI photographer and a veteran AP writer. The founder of the Burbank Symphony Orchestra and the president of the Southern California Chamber Music Society. A pair of Christian Brothers. A professor of theology, a pastor, and a nun. An author named Arthur, an architect named Aaron, and an artist named Alois. The owner of a textile firm and a textile executive. The former president of the American Paper and Pulp Association and the former president of the Institute of Scrap Iron and Steel. The inventor of alternate side of the street parking and one of the founders of Evelyn Wood’s course in alternate word reading. Two economists. Two obstetricians. Cary Grant and Desi Arnaz.

This is not craziness. It’s careful newspaper reading. Afterward, I wash the newsprint off my hands and think about universal harmonies. I think about things I haven’t thought about since childhood, such as guardian angels. I used to believe we each walked around with a sort of ghost of ourselves watching over us and guiding us. Is it possible that instead of a guardian angel, we each have a double, a kind of guarantee that our work gets done? If we’re the sort who isolates alphabet vitamins, there are two of us, just in case. If we are Cary Grant, Desi Arnaz backs us up.

One friend of mine used to collect “bus plunge” headlines. You’d be amazed how easy it is to collect such a thing. Buses plunge over cliffs and canyons across the world, and newspaper editors seem resigned to the sameness and predictability of such a universal death. Nearly every headline reads, SO MANY KILLED IN SUCH A COUNTRY’S BUS PLUNGE. Recently, the Times reported, 10 DIE IN BRAZIL BUS PLUNGE, though it wasn’t even a bus that plunged. It was a truck. But the convention persists.

Since reading the obituaries with the kind of attention one might give to a collection of poems, I’ve been thinking of bus plunges as the generic passing. Many of us took the plunge yesterday. What did we have in common? We happened to be riding the same bus. Perhaps the bus is literal—ten of us over a precipice in a south Brazilian state. Or perhaps it is metaphoric––an imaginary bus that one day encapsulates two vitamin scientists and another day bears a cargo of handmaidens to Hollywood.

The bus is an attempt to grasp the unthinkable, of course: one day, we’re riding along on the highway; the next, we plunge out of sight. Who knows who might be sitting on the seat beside us?

Last December, the editor-in-chief of the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists and the lead guitarist for a rock group called the Blasters plunged together, and I mourned them both.

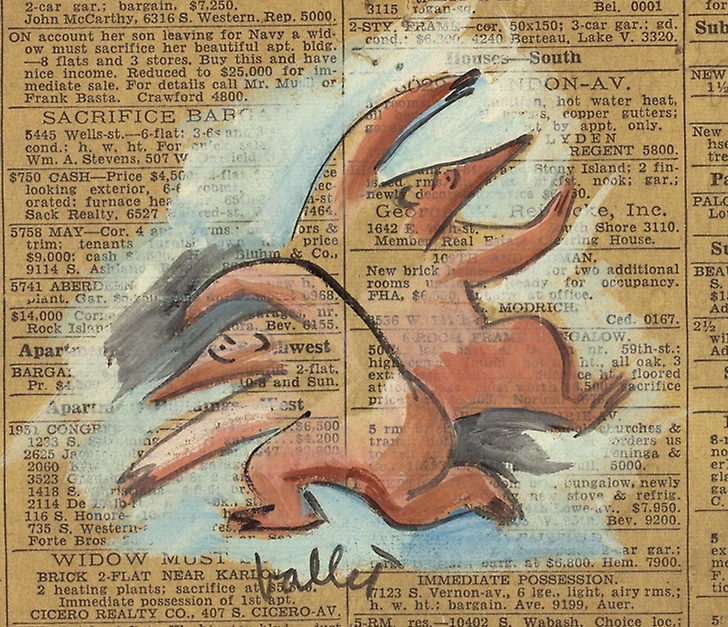

[Photo Credit: Edward Gorey c/o The Art Institute of Chicago]