In the end, one of Tony Conigliaro’s longtime friends said it best.

“Did the guy ever have any luck at all? Any?” asked Bill Bates, a former trainer for the New England Patriots. “Never. Zero.”

From his Fenway Park debut, on April 17, 1964, until August 18, 1967, when he was beaned by the California Angels’ Jack Hamilton, Tony C was the perfect ballplayer, in the perfect place, at the perfect time. The 1960s were a decade of extremes, one that began with dreams of Camelot but ended in the terror of Altamont, a time of tremendous promise and terrifying violence. Tony C embodied the hopes and fears of the era as no other ballplayer could. He was young, handsome, and oozing with talent when all three traits were worshipped. That he was a Boston guy made him even better. In a society enamored of youth, in a city that craved a hero, in a sport that needed energizing, for a team that sorely lacked those qualities, Tony C represented a limitless future.

In every sense of the word, Tony C was a swinger.

He first commanded attention with his bat, Tall and lean, at 6-3 and 190 pounds, muscles tightly wound and stretched to the breaking point, Tony C epitomized the powerful, young, aggressive hitter old baseball men spend half their lives looking for. He had the swing. Viewing the 19-year-old Conigliaro for the first time, Ted Williams commanded, “Don’t change.”

“He was so perfect,” recalls teammate Rico Petrocelli. “He fit in so well with being a major league ballplayer. A young, single guy in his own hometown. It was amazing.”

Buoyed by an adolescent’s blind confidence, Conigliaro hovered over the plate and dared pitchers to throw it past him. He swung hard and often, and he could scarcely believe it when he missed. In the pantheon of Red Sox sluggers, Conigliaro alone was made for Fenway Park. He was that rarest of things, a natural pull hitter with power. His talent was prodigious, his potential unlimited.

In 1964, as a 19-year-old major league rookie, Conigliaro hit 24 home runs, more than any other teenager in big league history. At 20, he led the American League in home runs, the youngest champion of all time. He hit his 100th homer at 22, again the youngest player ever to reach that mark. By the conclusion of the 1967 season, after only four seasons, he had hit 104 home runs. He accomplished all that despite being injured and missing a total of 144 games, which would have been worth perhaps another 30 to 40 more homers.

Off the field he was no less precocious. As he later observed, “When you’re a major league baseball player and you ask a girl out, she’ll go.” Girls loved Tony C, and Tony C loved girls. If love was all you needed in the sixties, then Tony C had it all. He was Beatles-cute, bashful, and brash at the same time—a typical kid, in a most untypical profession during the most atypical time in recent history. He liked fast cars, late nights, Revere Beach, and rock and roll. He appeared in a movie, made records, sang in clubs, dated beauty queens, and still hit the slider over the Wall.

Born in Revere and raised in East Boston as a Red Sox fan in the age of Don Buddin, Conigliaro went to St. Mary’s High School in Lynn. In 1962 he was signed by Red Sox scout Milt Bolling for $45,000. He bought a Corvette. That fall the Sox sent Conigliaro to the instructional league, where he saw good curveballs for the first time and hit .220. Disappointed, he spent the winter in the basement of his parents’ Swampscott home, swinging a leaded bat and working part-time as an extra in Otto Preminger’s film The Cardinal. The following spring the Red Sox assigned him to Class A Wellsville, in the New York–Pennsylvania League. After going hitless in his first 16 at bats, he finished the season with a .363 average and was named league MVP and Rookie of the Year. He was 18 years old.

When the veterans called him “Bush,” Conigliaro lashed out, fighting for his time in the batting cage, refusing to take any crap, and generally being a pain in the ass.

In November, President John E Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas. In February 1964 the Beatles appeared on The Ed Sullivan Show. In March, Tony Conigliaro went to spring training in Scottsdale, Arizona, and became Tony C.

The Red Sox were terrible, but the farm system was bursting with talent. Baseball rules then required teams to keep a certain number of bonus babies on the major league roster. Tony C was determined to stay.

During an intrasquad game on March 6, he homered. Boston baseball writers jumped on the “local boy makes good” bandwagon, figuring, like everyone else, that Tony C would soon be farmed out. In the meantime, he was an easy story.

But he kept hitting. Though ignored by most Red Sox veterans, Tony C refused to be intimidated. When the veterans called him “Bush,” Conigliaro lashed out, fighting for his time in the batting cage, refusing to take any crap, and generally being a pain in the ass. He was precisely what the Sox needed. The writers loved him. “If he doesn’t aggravate someone into murdering him,” one columnist observed, “he may become one of baseball history’s true superstars.” He was the Sox’s most colorful rookie and best young hitter since Ted Williams some 25 years before.

He was having a blast. Scottsdale was nothing like Swampscott. When he wasn’t hitting home runs, he was hitting on girls and discovering rock and roll. Conigliaro, Petrocelli, Tony Horton, and other rookies hung our at a local bar called J.D.’s. “Downstairs was rock and roll, upstairs was country and western,” recalls Petrocelli. “They had a live band and Tony would sing.” (Upstairs was an unknown country and western singer named Waylon Jennings.)

On March 22, Conigliaro elbowed his way into the starting lineup. In a 5-4 loss to Cleveland, he hit a home run to center field. No big deal—usually. But this center field fence was 30 feet high and 430 feet away. Only Ted Williams had ever homered to the same spot. A few days later Sox manager Johnny Pesky made official what was already apparent to everyone. Although he would play most of his career in right field, Conigliaro became the new Red Sox center fielder.

The timing was perfect. People had been looking for a hero ever since John Kennedy’s death, the previous fall. Young and handsome, Conigliaro was tailor-made for the role. All he had to do was perform on the field, and that was hardly ever a problem.

The Red Sox season was scheduled to open on April 15 in New York. It rained. Conigliaro awoke, looked outside, ordered breakfast, and went back to bed. His roommate, Frank Malzone, was already up, visiting with relatives. “He was a youngster and I was a veteran,” recalls Malzone. “I think they were thinking I could lead him in the right direction.” Conigliaro didn’t need much direction. But he did need an alarm clock.

The weather cleared and although the game was canceled, the Sox scheduled a workout. Conigliaro slept on. Then he finally awoke and learned of the practice, he jumped in a cab. The cab broke down. Conigliaro was 45 minutes late.

“I ought to be fined $1,000,” Conigliaro blurted to the writers. “I ought to be suspended.” An understanding Johnny Pesky let him off with a stern warning and a $10 fine. “What a way to start my career,” moaned Conigliaro. “I can hear my kids asking me someday, ‘What did you do your first day in the big leagues, Daddy?’ And I’ll say, ‘I slept.’” As a ballplayer he was still a rookie, but Conigliaro was already a veteran at being Tony C.

Things went better the following day. The Sox edged New York 4-3 in 11 innings. From the beginning, it was a typical Tony C day, equally exhilarating, exasperating, and endearing. In his first at bat he hit a scorcher that Clete Boyer at third nearly turned into a triple play. In the second inning he made a fine catch off Tom Tresh; later he singled and scored a run. He also accused Yankee pitcher Whitey Ford of throwing a spitter. Rookies don’t normally do things like that, but Tony C, obviously, was no average rookie.

“What do you expect a 19-year-old kid to do who has 700 women chasing him, become monastic?”

The Sox opened at Fenway Park on April 17. Fans picking up the Boston Herald found a smiling Conigliaro on the front page above the caption “Dream Come True.” For a benefit for the Kennedy Library, Fenway Park held 20,123 fans, including Jackie Kennedy, Caroline, John-John, and a host of politicians and celebrities.

Batting in the second inning, Conigliaro knocked White Sox pitcher Joel Horlen’s first pitch onto Lansdowne Street. Watching Conigliaro running around the bases, the crowd stood and cheered with joy. The future looked bright. Halfway between first and second, Tony C smiled and shook his head in wonder, then bounded on to be embraced by his teammates in the dugout. Had they been able to reach him, the fans would have done the same.

The remainder of the 1964 season was a dream for Tony C. By June he was receiving 200 letters a week, most from young women. The Globe’s Harold Kaese started comparing Tony C’s rookie year with Ted Williams’s. In July he wrote a feature story headlined, “Will Conig Follow Ruth, Speaker, to Hall of Fame?” Kaese speculated about who, after Williams, would be the next Sox star to make it to Cooperstown. “Possibly Carl Yastrzemski or Dick Radatz,” wrote Kaese, “but more likely Tony Conigliaro,” Heady stuff for a 19-year-old.

Usually, Tony C kept his head. No matter what else he did, baseball still came first. He missed curfew in July and was fined $250 by Pesky, who commented, “He doesn’t do anything wrong—he just wants to stay up all night and sleep all day.” Conigliaro proceeded to homer the next day before being hit by a pitch and sidelined until September, The injury cost him a shot at several rookie records, but he still made the All-Rookie team. (The Twins’ Tony Oliva, who won the batting title, was named Rookie of the Year.)

The off-season between 1964 and 1965 was a great time to be young and a great time to be Tony C. He delighted in his fame and popularity, taking great gulps of fun. “The girls naturally liked him,” recalls Petrocelli. “Tony had his pick of beautiful girls,” Adds Bill Bates, who met Tony C while walking across the bridge near Fenway Park, “What do you expect a 19-year-old kid to do who has 700 women chasing him, become monastic?” Tony C avoided the priesthood.

But he could not avoid the limelight. Recognized at a Framingham nightclub, Tony C took the stage and sang. Ever since the Beatles had stormed the States the year before, talent scouts and agents had been scouring the nation for similar talents. Tony C was spotted.

Within weeks later he was in the recording studio. He signed with agent Ed Penney, who also represented Nat “King” Cole and Burl lves. Penney formed his own label, Penn-Tone records, solicited a few songs, and committed Tony C to wax.

His first record debuted on January 19, 1965, at a press conference at the St. George Hotel. The A side was a rocking tune, “Playing the Field.” The B side was the ballad “Why Can’t They Understand?” According to Tony C, the B side was dedicated to the umpires, the A side to himself. He described his style as “the Beatles with a crew cut.”

Within a month, the record was number 14 in Boston and had sold 14,000 copies. Conigliaro’s four-year contract with RCA had a potential value of $100,000. There was talk of his making an appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show or Shindig. The Red Sox even became worried that their center fielder might give up baseball, but he quieted the concern by announcing that the singing career was strictly part-time.

Tony C had a vintage year in 1965. He led the American League in home runs with 32 and led the Sox to a .500 record before getting hurt. There was just as much happening off the field. Tony C, as they said back then, was smokin’.

Not drugs, though. “If you smoked a cigarette around him,” says Bates, “he didn’t care to be around you. If you did dope, you’re lucky if he didn’t tear your face off.” Tony C was smokin’ the entire scene, taking it all in, holding on, and having fun.

One wild week and a half in July summed it up. Fresh from being benched for playing his phonograph on the team plane following a loss, he went with Horton to a party while the team was staying in New York. Tony C miscalculated, drank too much, and went off into the night with several women. Horton made made it to the Commodore Hotel, only to be awakened at dawn by a call from a woman in Greenwich Village who demanded that Tony C be taken home. Horton and Mike Ryan retrieved the young slugger who was half naked and half out of his mind with alcohol.

There was no sobering Conigliaro up. On the bus to Yankee Stadium, he threw up into a writer’s lap. Manager Billy Herman got wind of what was happening and told Tony C he was benched. When Tony C insisted he was fine, Herman called his bluff and put him in the lineup. For nine long innings Tony C suffered the dry heaves in the House That Ruth Built.

Although the writers kept the details out of the paper, Conigliaro’s father, Sal, read between the lines and insisted on a meeting when the team returned to Boston.

Properly chastised and relieved of $500, Tony C responded with his best day of the year. In a doubleheader loss to Minnesota, Conigliaro smacked five hits—including his 17th home run—again inviting comparisons to Williams, who in 1956 had responded to a fine in the same fashion. That was Tony C. “When he got angry,” says Petrocelli, “he went out and played better.”

That wasn’t all. Earlier in the year he’d seen a photograph of Miss Minnesota, Elizabeth Carroll, in a Minneapolis newspaper. Conigliaro, being Tony C, sent her his photograph and visited with her family on a road trip. When the Sox left Minnesota, he told the writers, “She’s perfect in every way. She’s the girl I want to marry. This isn’t just today or tomorrow, it’s forever.” Or at least until the party in New York. Tony C, rock and roller, had a romantic side.

Two days after his explosion versus the Twins, it was Carroll’s turn to visit. She stayed with Conigliaro’s family in Swampscott, went to the games with Tony’s father and brother Richie, posed for photographers, and said all the right things. After all, she’d won the title of “Miss Unity” at the Miss USA Pageant. Tony C certainly kept it together in her presence.

What else could happen in a Tony C week? Why do boxers hit harder when women are around? With Carroll in attendance, Conigliaro had the best day of his career. While the Sox dropped two to Kansas City, he hit three home runs and missed a fourth by inches.

The rock and roll turned roller coaster. The next day a pitch by the Athletics’ Wes Stock broke Tony C’s right wrist, forcing him out of the lineup for 22 games but freeing him to escort Carroll until she left, still a Twins fan.

Marriage wasn’t meant for Tony C, and he needn’t have worried about telling his children about oversleeping on his first day in the big leagues. As Conigliaro wrote later, “I made up my mind not to get married until I got my complete fling out of life. I can’t imagine living with one person the rest of my life.” Carroll faded from the picture and Tony C started playing the field again.

Living life as if all dreams were destined to come true, not bothered by his tendency to get hit by pitches, Tony C moved from his parents’ home into Boston. That’s where all the action was. He and Tony Athanas, son of Pier Four’s Anthony Athanas, moved into a 10th-floor penthouse apartment at 566 Commonwealth Avenue. Gazing off the balcony, Tony C could see over the Green Monster to his own private field of dreams, right field at Fenway Park.

Kenmore Square teemed with students and was the center of nightlife for what was starting to be known as the younger generation. With Bill Bates, Tony C and Tony A prowled and played through the night, forming a bond that would last 25 years.

Tony Athanas was the A-man, Bates the B-man, and Conigliaro the C-man. “Tony was gregarious, in a shy and unassuming way,” says Bates. “He was never like, ‘I’m Tony Conigliaro.’ If we went into a bar, the three of us, we would stand against a wall and just chat. I’m not saying we were models of civility. We just had a good time like everybody else.

The endless summer of 1966 begat 1967’s summer of love. Wonderful and weird.

“Then, the clubs were what we called dating bars—guys with big lapels and bell-bottom pants, girls wearing pink hot pants and miniskirts, kind of a Goldie Hawn look,” says Bates. In places like the Psychedelic Shack, Where It’s At, and Inside Out, the three friends, like millions of other young people all across the country were cramming as much fun as they possibly could into every moment. The future? It’s now.

On the field, Tony C adopted a different attitude. He played hard but worked even harder. “I’ve been in locker rooms many, many years,” says Bates, “but I can say without equivocation that I’ve seen no competitor as fierce as he. Got his sleep every night, ate the right foods, was always in shape, He was so intense, it was incredible. He was always swinging that leaded bar and saying, ‘Top hand, top hand. It’s all top hand.’ ”

For Conigliaro, 1966 was much like 1964 and 1965, which is to say he was one of the Sox’s most productive players and one of the best power hitters in the league. For the second time in three years he outslugged Yaz. More mature and self-assured, he still marched to his own rock and roll beat, but it had become steadier and more controlled.

He put out another record, the infamous “Little Red Scooter,” backed by “I Can’t Get Over You.” Most of the Red Sox viewed Conigliaro’s singing career with more curiosity than disdain, but that didn’t leave Conigliaro immune from the occasional barb.

“We used to kid him about his singing,” says Petrocelli. “I think it was his record ‘Little Red Scooter.’ He came in the clubhouse and put copies of the 45 in everybody’s locker. When he went outside we all got together and put the records back in his locker, like we didn’t want them. He laughed.”

Rock and roll remained acceptable in trainer Buddy LeRoux’s room in the clubhouse, where Conigliaro hung out with Ryan, George Scott, Dalton Jones, and Joe Foy. The Sox were still terrible, but at least this generation liked one another.

The endless summer of 1966 begat 1967’s summer of love. Wonderful and weird. Dick Williams thought he was Bill Carrigan, the Sox manager of the glory teens. Jim Lonborg did his best imitation of Joe Wood and Scott a version of Jimmie Foxx while Yastrzemski played Teddy Ballgame. Tony C was in sync with Tony C.

Yaz was hot early while Conigliaro struggled. Deciding on a pitching rotation, the Sox hovered around .500 until Yaz cooled off. Conigliaro took the lead for a while. The Stones’ “Out of Time” was a more appropriate theme song than “The Impossible Dream.”

That phrase appeared in a Globe headline for the first time after a Sox victory over Chicago on June 16, The game was scoreless through 10, but in the 11th, with two out and Joe Foy on first, Conigliaro came to the plate, He swung twice and missed, then watched three balls. He drove the next pitch into the screen. For the first time in recent memory the entire team emerged from the dugout and welcomed Conigliaro home, while 16,775 fans caught pennant fever and started dreaming.

Conigliaro and Yastrzemski started in the outfield at the All-Star game. The Red Sox refused to drop out of the race.

The night of August 18 was hot and muggy, the air thick. Mired in a small slump, Conigliaro was determined to bust out.

The game was scoreless through three innings. In the fourth, after George Scott was thrown out at second trying to stretch a single, someone threw a smoke bomb into left field. It was eerie, as if the rioting and turmoil that was starting to rock the nation had accidentally spilled into Fenway Park. The summer of love was just about over.

For 10 minutes, play halted while the smoke slowly drifted over center field and dissipated. Reggie Smith flied to center and Conigliaro stepped to the plate.

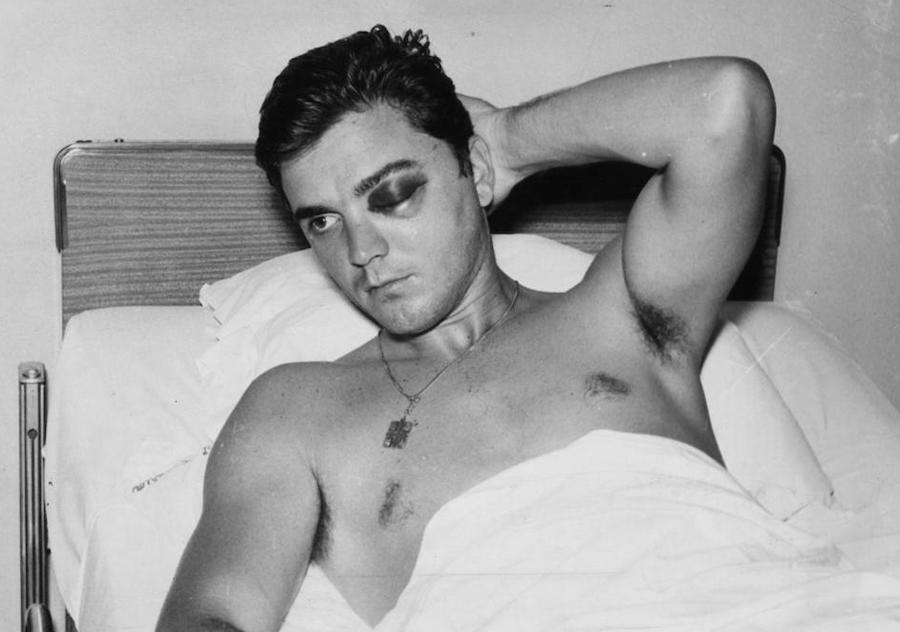

At 8:42 p.m., Conigliaro’s life changed irrevocably. He sprawled face-down in the dirt, his eye imploded by Hamilton’s errant pitch. While the Red Sox would go on to win the pennant, Tony C’s time had passed. On April 4, 1968, the same day Martin Luther King was assassinated, Conigliaro retired. His vision cleared enough to allow him to make it back into the Red Sox lineup to open the 1969 season, but the tragic nightmare that was to last the rest of his life had begun. In 1970, after he slugged 36 homers and knocked in another 116 runs, the Sox traded Tony C to California. Although he enjoyed the sunshine, dating starlets and living next door to Raquel Welch, he felt isolated and out of place. Then his vision deteriorated. Halfway through the 1971 season, Tony C retired again,

But he loved baseball and couldn’t resist trying to play one more time. He talked the Red Sox into inviting him to spring training in 1975. He beat out rookie Jim Rice for the designated hitter’s job and opened the season in the starting lineup. Injuries and continued eye problems forced him to the minor leagues and finally into permanent retirement.

On January 9, 1982, while being driven to the airport by his brother Billy, Tony C had a heart attack. He suffered brain damage and spent the remaining seven years of his life under constant care, imprisoned in his own malfunctioning body and only dimly aware of his surroundings. On February 24, 1990, Tony C died of kidney failure. The darkness that had begun on August 18, 1967, finally lifted.

One month before the beaning, on July 17, 1967, Tony C had released his last record. The B side was a Dixieland tune called “Please Play Our Song.”

The A side, the side Tony C thought of as his song, was “Limited Man.” It ended with these lines:

Because life doesn’t have a limit, life doesn’t have a plan

I cannot spend my limited life

Living like a limited man

Postscript:

It was an important story for me, and then almost everything went wrong. I was only four years into sometimes writing for money and a semi-regular gig at Boston Magazine had recently run its course. SportBoston was a new title in what the publisher hoped would be a series of city-based glossy sports magazines, sort of a local version of Sports Illustrated.

Tony Conigliaro was still a big deal in Boston, his already tragic story made even more so after the 1982 heart attack and stroke that left him partially paralyzed and brain-damaged. A friend had given me a 45 from Tony C’s brief singing career and I was hooked. I thought his story, set against the backdrop of the 1960s, would have some resonance. It did, but not quite as I anticipated.

As I worked the story, a friend at a North Shore daily newspaper broke the rules and allowed me to borrow the fat folder on Tony C from the paper’s morgue, a real help in the days before you could call up old newspaper stories online. Supplemented by research at the Boston Public Library, where I worked, I was in the middle of my reporting and had already spoken with former teammates and friends. A last interview, with Tony C’s close friend Tony Athanas, son of Boston seafood the restaurateur Anthony Athanas, was scheduled.

Then, on February 24, Tony C died of kidney failure. I don’t remember how I heard, but Athanas, apparently stricken by grief cancelled the interview. My deadline became as close to yesterday as possible so the story could run in the next available issue. I also received a panicked call from my friend at the newspaper; he needed the morgue file back NOW. A Keystone Cops scramble followed until he retrieved the file.

I started working on the story a day or two later, already knowing I had the perfect haunting kicker, Tony C’s last recording. On March 2, I received a phone call. My mother, who had cancer and had suffered a minor stroke some months before, had died of an aneurysm while undergoing an MRI. She was 57.

Lugging my portable electric typewriter I went home to Ohio, and as my father cried the house grew crowded with my mother’s Newfoundland family. They filled our home with music and laughter to match the tears – I remember my uncle Dan telling me about when baseball first came to their isolated outport, brought back after a family that had moved to Brooklyn returned. I periodically ducked into the basement, finishing the story, then drank whiskey and sang through the night until the funeral a few days later. The story appeared in May and within a few months, I improbably was named series editor of The Best American Sports Writing, landed my first book contract and soon stopped doing regular magazine work.

That was almost 100 books ago. My mother never saw any of them.