Cleveland State University hired Kevin Mackey to coach men’s basketball in 1983, the summer I graduated. No one gave a shit, me least of all. The team had gone 8-and-20, and Mackey was some no-name Boston College assistant. Besides, like a lot of CSU students, I was older, married and working for a living. We came to campus for classes, bolted coffee at the snack bar, and took the bus to the job. For us, that was college. There were no dorms, unless you counted the flophouses a block away on Prospect Avenue, where fraternity boys jeered at the working girls in their spike heels and buttcheek-high skirts.

We did have two student newspapers, one for blacks, one for whites. The most active on-campus social group was the local branch of the American Nazis. They wore brawn shirts with swastika armbands while they signed up new members in the student center. Every year, on Rudolf Hess’s birthday, The Cauldron—the white paper—ran their letters to the editor asking the Allies to release Hess from Spandau Prison. My most memorable moment at CSU, besides the day I met my wife, came when I took a piss in a University Tower john and looked up to see the twin lightning bolts of Hitler’s SS inked onto the wall above the urinal, beneath the words “WE ARE BACK.”

What I’m saying is that CSU was a fine place to get out of for a muddling Jewish boy from Cleveland Heights. And it was the perfect setting for an Irish guttersnipe like Kevin Mackey—who’d made his bones recruiting hungry city kids no one else could find or would take—to begin his head coaching career.

What he did his first three seasons at CSU was win sixty-four games. By 1986, his Vikings went 27-and-3 and in the NCAA tournament for the first time; I was a teaching assistant in Iowa City and Mackey’s only fan west of the Cuyahoga River. On the day CSU played Bobby Knight’s Indiana Hoosiers in the tournament’s opening round, I canceled “Forms of Comic Vision“ and invited the class to watch the game with me. The few who showed up at my house—all corn-fed, small-town, blond-haired Big Ten pinheads—looked smug, too polite to laugh, when I told them that CSU was bound to win.

That day—March 14, 1986—the rumpled-suited, fast-talking Mackey dealt Knight his first loss ever in an opening-round game and made me proud to be from CSU. Afterward—after the all-black Vikings outshot, out-rebounded, outhustled and outsmarted third-seeded Indiana; after the plump and shining Mackey shook the dour Knight’s hand, raised both fists, and punched the sky; after my students went home—I drank myself full of beer, lit my victory joint and cried for joy.

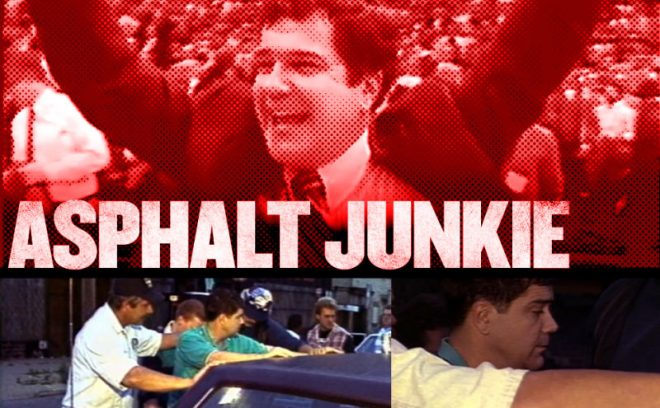

On the evening of Friday the thirteenth, July 1990, Kevin Mackey is passed out on a couch inside a crack house on Edmonton Avenue. His party started the night before as it always did, just him and a cooler of Lite iced down in the back seat of his Lincoln Town Car as he cruised the Cleveland ghettos, scouting summer-league games and getting drunk.

Somewhere in the previous night, he recruited a couple of strawberries—young crack whores—and the next morning, before heading back to the house on Edmonton, they all drove to campus together to snag Mackey’s paycheck, the first issued to him under his brand-new, two-year, $350,000 contract, announced only two days before.

Now, after nine hours at the crack house with his fast new friends, Mackey is unconscious. It isn’t only the beer and the wine and the crack and the women. Mackey (who says he faints during blood tests) has two big venipunctures—needle pokes—in his upper thighs.

Meanwhile, acting on a phone tip, the Cleveland Police Street Enforcement Unit has been staked-out at the corner of Eddy Road and Edmonton for nearly five hours, and Sergeant Ray Gercar has a headache so piercing that two years later he will recall asking one of the women stumbling out of the two-story house at 12406 Edmonton if she has any aspirin.

Gercar calls in the plates on the Lincoln at the curb: It’s Mackey’s. No reports of its having been stolen.

Farther up Eddy Road, near St. Clair Avenue, a news crew from Channel 8 waits too. They’ve got a camera on the scene, and their handsome young reporter, Martin Savidge, dispatched by the head of the station’s “I-Team“ after another mysterious phone tip.

No one rings Mackey’s wife, Kathy, and their three kids, at home in Shaker Heights, but somebody does phone Alma Massey, Mackey’s longtime lover, to tell her that her boy’s in deep shit. Massey, a heroin user and former prostitute whose police record dates back to 1974, knows where to find him. But rather than go directly into the house when she arrives, she instead pretends to slash the tires on Mackey’s Town Car.

Gercar figures Massey’s just playing it safe, trying to lure Mackey out. Maybe Massey smells cop. The crumbling house has been a known drug nest for some time, and Mackey, according to Gercar’s sources, is a frequent patron.

Everybody waits in the summer twilight, waits for Mackey.

Finally, the coach wobbles out, pasty-faced, disheveled, in an aquamarine polo shirt, khaki pants and white sneakers, a blinking, fucked-up, forty-four-year-old leprechaun groping in the dark heart of Cleveland’s Third World. As he and Massey climb into the Lincoln, Mackey behind the wheel, it’s 8:25 P.M. They turn north up Eddy, inching toward St. Clair.

The next thing Mackey knows, he’s up against the side of his midnight-blue ride, hands on the roof, as Gercar arrests him. The Channel 8 camera is already close enough so that on the videotape you can hear Alma Massey say “Would you mind gettin’ that out of my face?” in a polite, cold voice.

Mackey peers into the lens, deadpan, the skin slack on his chipmunk cheeks, jowls sagging, eyes lighting up as he struggles to outline a play in his mind.

At Sixth District headquarters, Mackey fakes two puffs into the Breathalyzer, reaches into his pocket and fires a hit of Binaca into his mouth, ruining any accurate breath analysis. Perfect. The defining moment, the sum and essence of Kevin Mackey, distilled into one Homeric act—Mackey the Gamin from Boston’s Somerville, Mackey the Spewer of Blarney, the Comber of Projects and Savior of Ghetto Youth, Mackey the bottom-line, ninety-four-foot, balls-out, how-many-fucking-games-have-YOU-won motherfucker.

Foxed them again.

Then Gercar hands Mackey a plastic cup, asks him to take a leak, and there it is, all of it, pissed away: the cocaine; the $350,000 contract, complete with new car, radio and TV shows, membership in the University Club, and 500 season tickets for inner-city kids in “Kevin’s Korner“; the chance to prowl the sidelines in the new $55-million, 13,000-seat arena they call “the House That Mackey Built“; the thirteen-room Shaker Heights mini-mansion with the pretty blonde wife and the swimming pool; and any prayer of Kevin Mackey’s ever again passing for someone young and on his way to the top.

Mackey holds an “I led two lives“ press conference, a sullen, teary public confession with wife, son and brother beside him. His lawyer negotiates with the school for a medical leave of absence, but six days after the arrest—plenty of time for local and national media to gnaw the carrion from the bones of the beer-swilling, crack-addled white coach and his black junkie hooker galpal—CSU shitcans Mackey.

Mackey does better in the Cleveland courts: Sentenced to ninety days treatment in Lieu of conviction, he splits his time between the Turning Point in Cleveland and former NBA star John Lucas’s Houston-based recovery program. After an additional few months in Houston, Mackey uses Lucas’s connections to get back on the coaching trail.

His first job is a $300-per-week assistant’s gig with the Atlanta Eagles of the United States Basketball League, with a contract stipulation that requires him to be tested at random for drugs.

After one USBL season, Mackey is named head coach of the Fayetteville Flyers of something called the Global Basketball Association. In February 1992, l rent a white Cadillac and drive to North Carolina. Mackey lives in a team sponsor’s motel room, hauls in thirty grand a year, and drives a Hyundai Sonata owned by a local car dealer. Sober since the day after his arrest, Mackey works off another chunk of his debt to sports and society via exile to this hardwood Elba, where the penitents suffer poorly laundered uniforms, chubby cheerleaders in washed-out spandex, and all-night bus rides between road games.

Spread from Albany, Georgia, to Saginaw, Michigan, the GBA is a touring hoops halfway house full of head cases, addicts and full-court lifers, guys whose dream of driving hard to the hole ended somewhere between the prison gym and a massage parlor. The salary scale for players begins at $9,500 for the sixty-four-game season and tops out at $25,000.

Fayetteville itself is pure GBA: Half the waffle houses, pawnshops, and strip malls in America are laid end to end here, crammed with soldiers, rednecks, and women with hulking, tortured hair. A blue GMC pickup parked in front of Uptown Undies and Stimulants sports a bumper sticker that reads “MY WIFE—YES. MY DOG—MAYBE. MY GUN—NEVER.”

Over at the Cumberland County Civic Center, hard by the Charlie Rose Agri-Expo Center, I find Mackey sitting alone at courtside and introduce myself.

“This is only about basketball, alcohol, and drugs, right?” he says as we shake hands.

The old twinkle in Mackey’s eyes has splintered into shards of blue and black. He’s pale, blotchy, thinner than in the CSU days, back when he loved to tell writers that “the modern game of basketball is a game of short, fat, white coaches and big, black studs.” He’s aged twenty years in two, the lines in his face etched too deep for a man of forty-six, even one whose entire adult life passed in gyms and barrooms.

Asking Mackey a question is like passing the ball to a shooter with no conscience: Once he’s got his hands on a thought, you’Il never see it again.

What Mackey doesn’t want to talk about, I quickly learn, is his wife and family, his relationship with Alma Massey and the mystery of who set him up with the police and the TV station.

Which omits all the why of Mackey’s life, how he got to this 4,300-seat dung heap with its photo-montage tributes to Elvis and Alabama near the ticket window, a million miles from glory.

“Home is where my job is,” Mackey says. “I’m very grateful to be here, to have this opportunity.”

Sure, but Kathy Mackey still lives in the house in Shaker, and the bank is foreclosing fast. Back in August 1988, Mackey forged his wife’s signature on an application for a $75,000 line of credit, using their home as collateral. According to Mackey’s attorney, the money went to Alma Massey and her seven children. Officially, the Mackeys are still husband and wife. Unofficially?

“My family is very supportive,” he says, “and that’s the end of that.”

How about Alma Massey?

“Look, I’ll give you plenty of stuff on the basketball, the alcohol, and the drugs. You’ll get everything you need.”

Fine. How about who phoned Alma from the crack house?

“I can’t give you that because that would open it up too good for you. She was called, and she put herself in jeopardy to come down and get me out of there and probably save my life, O.K.? She didn’t know anything. The worst thing that ever happened to Alma Massey was to meet Kevin Mackey.”

It’s not unfriendly, this game of keep-away, not without smiles on both sides. Savvy with reporters, Mackey needs his name in print, lest he be forgotten long before he gets another shot at the big money; there are plenty of younger coaches around with records just as good who’ve never been arrested on-camera after exiting a drug den. He also knows that I’m an addict too and a CSU grad, a native Clevelander undyingly grateful for every nanosecond of hometown sports glory.

As his players gather, Mackey shuffles onto the court and runs a light practice for an hour or so, hands the players their paychecks—something you won’t see Chuck Daly or Pat Riley do—and gives them some mild grief about the fact that they’re 2-and-4 in games played the day after payday.

“Ah, you guys put those checks in the bank. You don’t need to be out spending that money the same night you get it.”

Everyone laughs except Stu Gray, a seven-year NBA journeyman backup center who’s drawing half a million dollars from his last Knicks contract. Gray, the only white on the Flyers, smirks.

Mackey suggests a Hardee’s not far from the Civic Center when I ask him where we can go to have a bite and talk.

I tell him I’ll gladly buy him dinner somewhere nice.

“Nah. I just need some diet Coke.”

We drive the 500 yards or so to Hardee’s. Mackey digs the white-on-white Caddy.

“This yours?” he asks.

“No, no. I take the bus.”

“Nice. That’s all right. Where you staying in town?”

“Same place as you.”

A grunt. He doesn’t like that at all.

At Hardee’s, Mackey sticks to soda while I drink coffee-just two clean, sober men of the nineties, trapped in a frieze of fast-food orange, sparring over the details of his botched career. Mackey speed-raps from 5:30 until 10, pausing only to visit the men’s room to void the diet Coke. In the two ticks I once needed to chop and pop a brace of fat lines on a mirror, Mackey dashes off a thousand words, half of them variations of “fuck“; another couple hundred are the phrase “off the record,” tossed into the mix at irregular intervals as his rasp waxes into white noise.

The voice is all cracked Boston blacktop and broken glass, with an “ah-ah-ah“ stutter he uses like a dribble as he darts from sentence to sentence. Asking Mackey a question is like passing the ball to a shooter with no conscience: Once he’s got his hands on a thought, you’Il never see it again.

“I resented there were coaches making more money than me, who had better players to work with than me, who had better cooperation from the university, better facilities. But that’s just another excuse to medicate yourself.”

To Mackey, coaching is war, a test of strength, smarts and guts, and may the most ruthless urban gangster win. The college game is a “fucking farce“: Behind the scenes, millions of dollars flow from booster to assistant coach to player, everyone knows it, everyone’s a pimp or a whore. Even Catholic high school coaching, where he began, demands outlaw recruiting. That’s what makes whipping the Hall of Fame guys, the coaches who get the All-State players and most of the acclaim, so sweet to Mackey.

“How’d I feel after beating Indiana? Like I could’ve done that years ago if someone had given me the chance. Who the fuck is Bobby Knight? You see me running off the court? I couldn’t wait to go get fucked up. I couldn’t wait to get to the fucking bar. I resented there were coaches making more money than me, who had better players to work with than me, who had better cooperation from the university, better facilities. But that’s just another excuse to medicate yourself. Twisted, insane thinking. Once addiction kicks in, it takes anyone you love and anything you love and starts to eliminate it. In the end, it’s just gonna be you and the addiction. Then it takes you.”

Mackey’s down with this addiction talk, his full-court press built on programmed self-disclosure, honest self-abnegation and, in his case, relentless self-promotion. Each phrase he mouths across the booth at Hardee’s pops up in every article about him: His monkey is “baffling, cunning and powerful,” his life “a descent into hell,” his journey “a collision course with disaster.” If addiction is at root an ego problem, a need to keep the furnace of the self red-hot, Mackey is Etna.

But back to Cleveland, Mackey, Cleveland. I mention the late, great Sterling Hotel, the seediest of all the Prospect Avenue fleabags, and Mackey recalls it with a grin. Nearby was the New Era burlesque house, a square barracks of downscale sin where the distaff stars of the dripping screen appeared in the flesh. I saw Marilyn Chambers there once, flashing her nether lips and then hurling herself from the stage into the mucky sea of Neanderthals who’d paid $20 a head for a whiff of her fabled cooz.

“You sound like you miss it,” Mackey notes.

Of course I do—burning at nostalgia’s heart is always a core of loss, and where Ms. Chambers and her nipples once rose now stands the CSU Convocation Center in white-piped glory, its rafters hung with the banners Mackey’s teams earned in tiny Woodling Gym. He never coached a single game at the Convo Center. And there have been no tournament appearances, no new banners, since Mackey left.

I tell him that some folks say CSU was raring to fire him, that the talk of his alcoholism and philandering, added to a history of recruiting violations, made him easy to kiss off, despite all the wins and banners. One source at the school told me back in 1990 that “the university has a fairly thick file on such activities, including the drinking and numerous arrests for DUI.”

Mackey claims he was never actually arrested.

“There’s nothin’ on the record except a few speeding tickets, maybe seven,” he says. “You can look it up.”

When the cops did stop him—he admits he was pulled over a lot, “rushing to a bar”—he’d offer up a pair of sneakers or a basketball from the Lincoln’s trunk, throw in a fistful of game tickets, and party on.

“While you’re winning, you’re the king,” he says. “Nobody says anything, nobody sees anything, you can do no wrong.”

Then I ask Mackey about crack, what it feels like. I myself quit using everything in Iowa in 1988, threw out the Stoly and the three hits of blotter in the freezer, the bong and the one-hitter, the single-edged blades and the amber vials, even the rusty nitrous-oxide cartridge dispenser. For eighteen years, I’d done everything I could touch but the needle. But stuck in Iowa, I’d never smoked crack, and even now it kills the addict in me that I might have missed something even more crippling than angel dust.

“Beam me up, Scotty,” Mackey laughs. Then he pauses.

“I’ll tell you what it’s like,” he says. “What I went through? I didn’t hit bottom. ‘Bottom’ is a guy in the crack house with nothing to offer but himself. I’ve seen it, O.K.? Do you understand what I’m saying? He’s got no money, nothing else to pay with. And he’s gotta have it. You understand?

“I can go to bars to meet people or whatever—no problem,” Mackey adds, “but I know if I was around the crack again, it would suck me in. I can feel it inside me at any time. It’s almost like there’s another person inside. It just waits.”

Kevin Mackey grew up an altar boy and a playground rat in Somerville, a blue-collar Irish-Italian enclave just north of Boston proper. Both parents were teachers, and Mackey was the first of four kids. He says now that he was an alcoholic from age sixteen.

Mackey’s academic priorities were “basketball and cheerleaders.” At twenty-one, he was already married and coaching at Cathedral High in Boston’s black South End, where his first teams didn’t even have a gym to play in. No problem—he not only made the situation work for him, he discovered the key to the coaching highway: ghetto ball.

“I had to go beg, borrow, or steal places to play, and I had to find my own way around there. I got to see for myself what these people were going through, their dreams and aspirations, and I saw the talent—so talent-rich. I coached inner-city schools, and I became known as kind of an inner-city coach.”

Mackey’s flair for finding raw black talent in risky places quickly became legend. And if by chance you hadn’t heard of his reputation, he would gladly, loudly, fill you in.

“I go into the projects,” he would boast, “and they see a white guy in there, he could be one of two people, a cop or a coach. If you tell ‘em you’re a coach, you’re welcome. If you’re a cop, you gotta look out. They don’t bother me in the inner city.”

As Mackey hustled up Washington Street from Cathedral to Don Bosco, a New England high school basketball powerhouse, and then to Boston College as player procurer for head coach Tom Davis, his reputation defined his limits. He worshiped talent, especially small guards—the word comes out “gods“ in Mackey’s dialect—landing current Celtic John Bagley and NBA All-Star Michael Adams for BC. Adams he discovered in a Hartford gym; no one else had even offered the kid a scholarship. “I got goose bumps, I started to sweat, I hadda go to the bathroom, I was gettin’ chills,” says Mackey. “I wanted the kid outta the game. I wanted him to get hurt, not badly, just bang his knee or something. I didn’t want anyone else to see what I was seeing.”

For Kevin Mackey there’s always something more to say, about pressure defense, the Olympic team, his all-time starting five, you name it, so long as it’s basketball.

But while big-time schools need super-recruiters, when it comes to the man who runs the show, few risk choosing a street guy, a braggart, a tightrope walker. Everyone seemed to know that, except Kevin Mackey.

When Tom Davis left Boston College in 1982, Mackey, his assistant for four years, fully expected the promotion to head coach. Not only was he passed over, according to one Boston sportswriter, “he was never seriously considered. He was viewed as a bandit, a renegade, a guy who could get you in trouble down the road.”

Down the road, of course, was my alma mater, a state institute of semi-higher learning with an open-admissions policy, the academic reputation of Romper Room, and a silver-haired prexy with matched black poodles named Amos and Andy. Like many another urban college—Memphis State and UNLV leap to mind—Cleveland State in 1983 figured it would be simpler, cheaper and more fulfilling to build a high-profile basketball program than an actual university with a decent library and all that stuff.

Quicker, too.

According to the NCAA and to CSU officials, Mackey’s recruiting violations began within weeks of his arrival. Three years before his arrest and firing, he landed CSU on probation for recruiting Manute Bol, a seven-foot-six Dinka tribesman from the Sudan who spoke no English.

“They sniffed around for four fucking years, and that’s all they could come up with,” says Mackey. “I told the motherfuckers ‘Look at my guys—they’re wearing fake gold and driving old cars. For Christ’s sake, go find a program with real money.’ But they had one guy on the committee who was all upset because the Africans were taking scholarships away from American players.

“Besides,” Mackey goes on, worked up now, “Manute never played one fucking game for Cleveland State. We knew we couldn’t get him into school, but what were we supposed to do, send him back? He refused to go. His people were starving back there. The bottom line is, we got zero competitive advantage, none, and they hit us with three years fucking probation.”

No, I say, the bottom line is that the NCAA report says that CSU fed and housed Bol for a year, paid thousands of dollars to his English tutors and worked him out with the team, all serious violations. Which makes Mackey sound like a bank robber bitching that he got tossed in jail even though he didn’t get to spend the dough.

“But we got no competitive advantage,” he insists.

The administrator who says he knew Mackey best, Jan Muczyk, claims that the people who hired him received fair warning “from a very reliable source that in three years he [would have us] in an NCAA playoff and in four years he [would have us] or probation.”

As with every CSU person I spoke to, in and out of the athletic department, Muczyk’s memories of Mackey mingle a willful innocence with expressions of loss and betrayal you might hear on Divorce Court. Muczyk himself is a College of Business professor who negotiated Mackey’s contracts. According to a faculty member close to the 1990 negotiations, it was Muczyk who “referred to Mackey’s taste for African-American women as a ‘perversion.’”

Muczyk admits “there were rumors, including drugs, rumors that he’d hang around with sordid women.” When he confronted Mackey, Muczyk says, the coach assured him that the women were the mothers and the aunts of prospective players.

“I didn’t hire a private eye,” Muczyk continues. “I didn’t have the budget for that.” As for the citywide stage whispers about Mackey’s drinking problem, Muczyk says he tested the coach himself.

“I deliberately took him to a number of watering holes and offered to buy him strong alcohol—bourbon, scotch, whatever.”

The wily Mackey tricked Professor Muczyk by refusing anything stronger than Miller Lite. Case closed, except for the photo that Muczyk wants me to see.

“Look at this,” he says, holding it across the desk. “This one will bring tears to your eyes.”

There stand Mackey and Muczyk at a postgame party. Mackey looks fine, crisp and smiling, clear-eyed, a whistle around his neck. Muczyk is obviously shitfaced.

“I went to battle with him everywhere, everywhere. It took me a while to get over the feeling I was betrayed,” he says, and it’s plain that he never has. “Hell, the guy’s more sober than I am. He’s not wearing the stupid booster hat, you don’t see him holding a drink in his hand. Who’s got the problem in that picture?”

Mackey can’t remember the nine hours in the crack house, he says, because he was unconscious. Needle holes? Yeah, but who, what, and how, he just can’t recall. What’s left of self-disclosure is a twelve-step pablum cooked up for the straight reader, weak cheese that’d be stuffed back into his face if he tried it at an NA or AA meeting. And Mackey hasn’t seen a meeting room for a while.

It’s the women in Kevin Mackey’s life who bear the ugliest scars. Alma Massey spent her weekends in jail for two years after the police found heroin in her purse at the Edmonton Avenue bust.

“Nah,” he tells me, “I haven’t gone of late, which is not good as far as recovery goes. I’ve been very busy. But I believe in the meetings. My thing is to do the best I can with each day, and don’t pick it up. That’s worked very, very well for me.”

Maybe for him, but not for the people he hurt. Contact with his family is sporadic. In Fayetteville, he has no friends, only players. The younger brother who stood by him at the post-arrest press conference won’t discuss him now, refuses even my question about their age difference; they got into a fistfight upon Kevin’s release from the rehab program and haven’t spoken since. Mackey’s twenty-three-year-old son, Brian, a commodities trader in New York City, muses on his father as “tragic hero,” a man whose “dark spot started to grow larger and larger.”

Still, it’s the women in Kevin Mackey’s life who bear the ugliest scars. Alma Massey spent her weekends in jail for two years after the police found heroin in her purse at the Edmonton Avenue bust. Mackey’s relationship with Massey dates back to at least four years prior to the arrest. Channel 8 revealed an audiotape from July 1986, when Massey’s distraught mother phoned the station to claim that Mackey was funneling Alma $2,000 at a time for drugs and that the police wouldn’t do anything about it.

Massey, too, is sober now, and it’s clear from one brief conversation that she’s a bright, complex human who was distorted by the local media to fit the ghetto-wench stereotype. Offered thousands of dollars by the local media to tell her story, she refused. Now, she says, she’s struggling to get and keep her life and family together.

She’s also frightened. At first, she seems willing to talk—if we meet at her lawyer’s office, and if I’ll sign an agreement to quote her in full. What exactly do I want to know? But as soon as I pose a few questions about her and Mackey, she asks if I’ve been watching her house and tapping her phone. Then she’s gone.

Mackey’s wife, Kathy, is a small, brittle blonde who works as a jailhouse nurse-supervisor in the Cuyahoga County Corrections Center. She says she threw her husband out of their house when, on the morning after the arrest, he left to visit Alma. For Kathy Mackey, the betrayal continues: Her husband lied and kept on lying, even after his public scouring. To this day, she says, he hasn’t come to terms with his real problems or the pain he caused.

“Kevin has his own agenda,” she concludes, her voicee like his, a street-corner snarl, a cross between Betty Boop’s and Ma Barker’s. “My life was cut open and spread out on Euclid Avenue. The thing is, I would have lived with that man anywhere. I would have lived with that man in a tent on Public Square. It wasn’t the money. It wasn’t the fame. I loved him.”

The house at 12406 Edmonton still stands, barely, next to a vacant corner lot. No house number, but I know the place from the tapes: two slumped stories, a caved-in brick porch piled with garbage, peeling pale-green paint browned by filth. At high noon, a bare bulb burns in a ceiling fixture on the second floor; I stare at it from the street, safe inside the Avis Cadillac.

According to Sergeant Gercar, the place is back in business; at the Justice Center that morning, he warned me not to approach it even in daylight. So I sit a while, listening to Lou Reed, wondering what Mackey saw two years ago beyond that blank plywood door.

Later, I phone Mark Johnson, an Edmonton Avenue resident who saw the coach on the morning of his arrest, buying beer and wine at a little corner grocery on Eddy. Johnson spotted the two girls, too, waiting for Mackey out in the Lincoln.

Johnson admits that he’s the guy who tipped Channel 8 to Mackey. He says he was worried about the coach’s safety in that neck of the woods.

“He looked like he was ready to pass out. I called Cleveland State, also—[Merle] Levin. He told me there’s nothing he could do about it. I says, ‘Well, I thought maybe you guys would want to know.’ He told me he was busy.”

“Did you call the police too?” I ask Johnson.

“No way. I wasn’t the only one who saw him that day. I mean, he’s very visible down here. I called everybody I thought I could, and then I thought to myself, Well, nobody seems to care.”

Merle Levin’s title at CSU is sports-information director and assistant athletic director for marketing and communication. When I ask him about Johnson’s call, he skips a pass to John Konstantinos, the athletic director, hired only two weeks before Mackey’s firing.

Konstantinos says Johnson phoned him—three times.

“The first message I got was early afternoon. I had been out. It just said ‘Mark Johnson re basketball.’” Konstantinos doesn’t recall the second note, but says that he came home to find an unforgettable message on his machine.

“It said ‘Good news about basketball,’ and I couldn’t imagine what that was all about because I was supposed to meet with Kevin that afternoon and he didn’t show up.

“I called the guy, and he went through the whole spiel about how he had seen Coach Mackey earlier that morning, buying liquor. He said he checked and it was the blue Lincoln. There were two young ladies in it. He even gave me the license number. He said, ‘Is this your coach’s car?’

“Well, no sooner do I get off the phone with him than Merle Levin calls me—he was probably trying to call me while I was talking to MarkJohnson—to give me the news of what had happened, that Kevin had been arrested.

“I remember asking Merle, ‘Is this his license number?’ And he said ‘Yes,’ and I said, ‘Then the guy knew what he was talking about.’ I’ve never spoken with him since. I have no idea what he looks like. He sounded sincere.”

So does Konstantinos when I suggest that his account hints of, urn, a peculiar lack of concern about the basketball coach he’d inherited.

“Let me tell you, I did not welcome his demise. It created problems for me that I’m still living with.”

But isn’t he the guy who decided to dismiss Mackey rather than give him a medical leave?

“Yes, I recommended that he be fired. How could we maintain our image? What would I tell my thirteen-year-old son? How could we then go out and recruit? How could we get into a front room with Mom and Dad to sell them on the idea that they should send their young person to our care?

“The other thing was, no one could tell how long it would take to rehabilitate him. What were we supposed to do, put our whole program on hold?” But isn’t there at least the appearance of a setup put in motion by the same crew who’d just inked Mackey to a new deal?

“There was so much going on, and who knows what the truth of the matter is? Sometimes I think I don’t really want to know. I give ‘em an old Lou Holtz quote—‘The good Lord put eyes in front of my head instead of behind so I can see where I’m going instead of where I’ve been.’”

After the GBA season ends, Mackey will be named head coach of the Albany, New York, franchise of the Continental Basketball Association. It’s another step up—this is where Phil Jackson coached before he got the call from Michael Jordan’s team—but Mackey had loftier hopes. His old friend and role model Jerry Tarkanian might have taken him on as an assistant with the San Antonio Spurs, but when Tark phoned Mackey to pick his brain, Mackey told him straight out that the team had holes, serious holes, and Tark never called back.

“[Mackey’s] never gonna be an NBA head coach, no way,” says a Boston writer. “That’s too bad in a way, because he’d probably win ‘em a lot of games, but it’s exactly the same reason BC didn’t hire him when Tom Davis left. He was too dangerous.”

Sweet music to Mackey, a tune he can’t resist. Mackey in the NBA? Only a matter of time, he says. He’s got connections, a sexy winning percentage and no doubt about the warp of his whole life.

“All you’ve got to do is tell me I can’t do something, and I won’t stop until I do it. It’s a burning thing in me, it’s like a fire, to do well. Some people know how to win, know what it takes to win. I think I’ve demonstrated that throughout my career.”

In Fayetteville in February, with little for Mackey to work with, the Flyers’ record is 28-and-13. Mackey pockets an extra ten grand if the Flyers win the league, but the odds are long despite the current standings. His top three scorers have fled—one to the Philippines, two to Australia—for longer green. The schedule is grueling, and the players, desperate for a first or last shot at the League—that’s how one and all refer to the NBA, just the League, spoken with a pilgrim’s awe and reverence—are selfish, fierce, and angry on the floor.

The bush-league referees can barely trot and blow a whistle at the same time, much less control the game, but Mackey hardly baits them anymore. In one game, he shouts “This isn’t girls’ junior high!,” which draws a technical foul, but mainly he just seethes and silently takes another pull on his diet Coke. He’s still wound tight on the sidelines, never sitting, but he’s calmer than in the old days.

“I have to be careful because of what I went through,” he says. “I have to watch the way I conduct myself.”

Still, he’s not above illegally substituting one player for another at the free-throw line, knowing that these officials will never catch it. Neither will the opposing coach.

On an off night in Fayetteville, I drive Mackey to the WFNC-AM studio for a guest spot on Fanfare, an hour-long sports chat.

“Your segment is twenty minutes,” host Alex Lekas tells him, but forty-five minutes later, Mackey’s still on caller number two, swigging soda from a Big Gulp cup, cracking ice with his teeth. The pitch of his monologue makes the mike superfluous: If the caller turned off his radio and flung open his windows, he’d surely hear Mackey rumble against the sky.

“I’ll tell you,” Mackey spumes, “I’m grateful for the chance to coach in this league. The GBA is only a bounce away from the NBA.”

It’s maybe the tenth time I’ve heard Mackey use this same line—to his players, at a press conference in Raleigh, during a postgame radio interview, in the Hardee’s booth, and in my room at the Marriott. After practice the next day, I ask Stu Gray if it rings true.

Seven years spent trading elbows and riding the NBA pines from Charlotte to Indianapolis to New York left Gray short on front teeth but equipped with a rugged, war-tempered stare into the middle distance. He averaged only 2.3 points and 2.6 rebounds per game in the big show, but he was there.

“Sure,” Gray says after a while. “One bounce, or one million.”

Still, listening to Mackey in the darkened studio, it’s not so hard to believe. Just a stutter-step through the circle, a flex of the knees, an uncoiling of spirit and fast-twitch muscle and up they go, up from this outlaw outback, up into the League, all these men-children who, as Mackey says, have “come through the test of fire” that burns in the projects and the gyms and the bars and the straight glass pipe.

Won’t they need a coach?

“Hey,” he croaks to the caller, winding to full torque, “test me, test me. Anyone. Anyone who wants to pay me, who wants to give me an opportunity. Test me. Write it in the contract ad infinitum. What more can I say?”

For Kevin Mackey there’s always something more to say, about pressure defense, the Olympic team, his all-time starting five, you name it, so long as it’s basketball. The station break on the half-hour is long past due, but Alex Lekas just sits there, struck dumb while Kevin Mackey smolders on, belching diet Coke and the smoke of his soul into the far blue midnight.

[Illustration by Sam Woolley]