The night before I left for South Texas to join Willie Nelson as he went back on the road again to sing for the I.R.S., I had dinner with a woman from L.A. who’d known him. She told me a fascinating story about Willie Nelson, lost love, and the lost plutonium of sadness.

That wasn’t her phrase, “lost plutonium,” but deadly gamma radiation is what came to mind when she told me this, perhaps apocryphal, story about a secret stash of Willie’s most lethal killer sad songs.

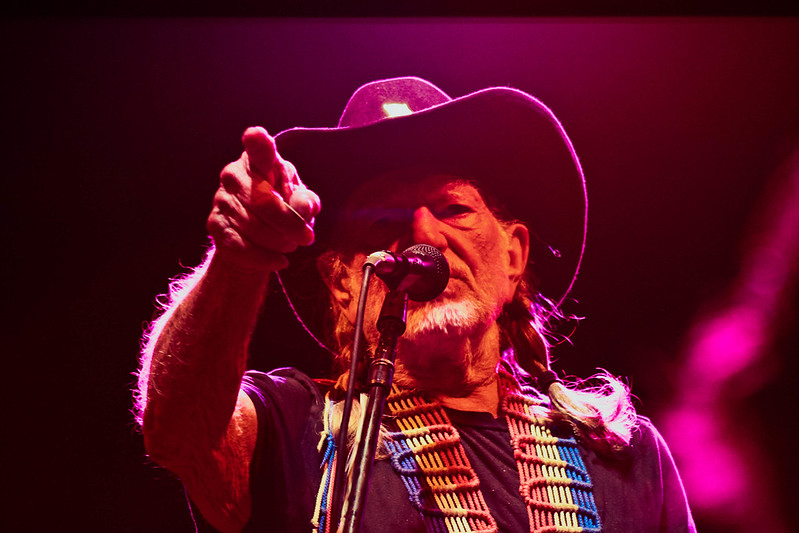

She framed the story by depicting Willie as quite the ladies’ man and heartbreaker. Despite his scrawny, pigtailed exterior, she said, all kinds of women swoon over him and not merely because he’s an American legend or because “ladies love outlaws” or because of some irresistible vibratory phenomenon in his voice and the emotion of his songs—although all of those factors certainly contribute. But there’s something more, one feature he possesses, she said, that magnetizes women in all walks of life, from waitresses to Hollywood princesses.

What’s that? I asked.

“His eyes,” she said, “those deep-set, mesmerizing eyes. He’s got Charlie Manson eyes.”

Well, as they say, whatever works. Other women have confirmed similar mesmerized reactions to those eyes, have noted Willie’s outlaw sex-symbol appeal, the Hollywood women, the trail of broken hearts. (And don’t forget the woman who recently accused him of breaching his verbal contract to marry her—claiming, among other things, that Willie made love to her for nine hours straight in one session, concluding with a spectacular backflip. “I’m not saying it didn’t happen,” Willie told a reporter, “but you would’ve thought I’d remember at least the first four or five hours.”)

But this woman from L.A., who was in a position to know (not that position), said there was one woman one time who really broke his heart. So badly, the story goes, that after she left him he took all the songs he’d written for her and about her and locked them away in a vault, never to be sung again. Because while Willie had already penned some of the most brilliant, painful, savagely sad songs there were, these were just too powerful, so unbearably sad he couldn’t stand to hear them again, much less unleash them on an unsuspecting world. They had to be locked away in a vault, like emotional plutonium, to protect the vulnerable (including him). Else people would be flying out of buildings so thick and fast it would make “Stormy Monday”—the legendary suicide song—look like Another Pleasant Valley Sunday.

O.K., there’s reason to be cautious about accepting this as gospel: it has a folkloric, lost-treasure-tale quality to it. But whatever the literal truth, it does define the thing that’s most distinctive about Willie Nelson’s songs, a quality that transcends country music, the outlaw image, the whole cosmic-cowboy aura about him. Which is the way his best songs cut to the heart like a surgeon. His special genius as a writer is his ability to evoke not just sadness, but dangerous sadness. That for me was the real source of mystery and wonder; that’s what I was hoping to find in my travels with Willie—if not the lost-plutonium songs themselves, then something about the primal source of that amazing fountain of sorrow.

CRAWLING FROM THE WRECK

A rainy day on Highway 31, outside Nashville. Willie’s on his way to Willie World —officially the Willie Nelson & Friends Showcase—to gaze for the first time at all the personal possessions the I.R.S. seized from him on that black day in November 1990 when they raided his Texas homestead and confiscated everything he had. All the mementos of his fifty-eight years, all the pieces of his life, from his gold records to his children’s bronzed baby shoes, are now on display behind velvet ropes in a Willie World exhibit for tourists—and Willie himself—to come gawk at. (The museum bought all Willie’s possessions at discount from the I.R.S.) For the past week Willie’s been trying to live for the future, getting out in the Honeysuckle Rose II, the tour bus that replaced the original (totaled in a head-on collision up in Nova Scotia last year), playing in beer joints and honky-tonks for his hard-core fans. And putting the finishing touches on the project that is his last best hope of getting out of the $15 million hole he’s in—two albums made up of never-before-released tracks from his vaults, albums that, through an unconventional deal with the I.R.S. (which now owns the vaults and the tapes therein), he’s going to be advertising first on late-night TV and that, if that doesn’t put enough of a dent in his debt, will then go into record stores. (In fact, they should be hitting the stores soon.)

Willie’s kept his spirits up on the road with strenuous attitude control. “I’m a fanatic about any type of negative thinking,” he tells me. “It’s kind of like, You better be happy or I’ll kick the shit out of you.” But after spending a week with him I could feel that consciousness of loss is not too far beneath the positive-thinking surface. And coming off the road to see his lost past, now on exhibit in a museum, is going to be a challenge.

You can feel the negative undercurrents even in his sense of humor, which for a moment there on Highway 31 turns very dark indeed.

Willie’s sitting up front in the passenger seat telling a joke about a car wreck to his buddies Larry Trader and Ben Dorsey, his spiritual adviser Jim Kimmel, and me. It’s a joke prompted by our collective near-death experience a bit earlier, in the course of a wild ride to a recording studio in a car driven by an attractive young woman, an aspiring Nashville songwriter, who got so distracted playing her demo tape for Willie that she almost got us all crushed by an eighteen-wheeler.

“This guy is goin’ down the road with his girlfriend,” Willie says, “and she’s foolin’ around with him, you know. The guy gets all fucked up and ends up in a big ol’ car wreck. Officer arrives on the scene, sees the guy walkin’ around in a daze looking for somethin’. Asks him what he’s doin’. Guy says, ‘I’m lookin’ for my girlfriend’s hand.’

“ ‘Her hand? Why her hand?’ the cop asks him.

“ ‘ Cause it’s got my dick in it … ’ ”

Not a pretty picture, the one conjured up by the punch line. But in a way it’s perfectly emblematic, compressing as it does into one elegantly expressive image all the key themes that make country music at its best, the kind of songs Willie writes, a gothic mirror of the wreck-strewn American emotional landscape. Themes like sex and death, emasculation and emotional mutilation, irrevocable loss.

A MEMORABLE KISS

Can Willie crawl out of the wreck the I.R.S. catastrophe has made of his life? And why should we care?

One night, as the Honeysuckle Rose rolled north through the Louisiana darkness after a rowdy Saturday-night gig at a roadhouse called Mudbugs outside New Orleans, Willie Nelson showed me the diary he’s been keeping since the I.R.S. trouble landed on his head. It was in one of those lined composition notebooks, every inch of the ruled sheets covered with Willie’s painstaking penmanship. I asked him to read me a selection, and after searching for a while he chose this one: “I’m trying to analyze myself to see what’s bullshit and what’s real. I found out that even the bullshit is real … It’s a real part of my personality. It’s not negative; it’s just bullshit.”

Before we go any further I think it’s worth addressing these questions: What’s real and what’s bullshit about Willie Nelson? Why should we be concerned about his losses? Isn’t he just another celebrity in a fix, another country-music crack-up? Sure, we all like to read about fallen idols, fallen angels, and superstar fuckups. But what has he done to deserve our sympathy?

The bare facts only tell part of the story. A Depression-era baby (born in 1933), Willie was raised by churchgoing, music-teacher grandparents after his wild-at-heart teenage mom ran away from the flat featureless farmland of Abbott, Texas, to seek excitement on the West Coast—when Willie was only six months old. He started winning gospel-singing contests when he was nine, and before long he was also playing beer joints with polka bands and a western-swing-style group called Bud Fletcher and the Texans. “I found out there’s no difference between a beer joint and a church,” he told me. “Both sets of people I saw in both places were having a good time.” Both kinds of music had the same message—about faith and unfaithfulness. “It’s just that,” Willie says, “in one of them, the lights were a little darker.”

Not long after that, his teenage bride, Martha, talked Willie into moving to Nashville to peddle his songs. In no time, Willie became an overnight success as a songwriter when, in quick succession, Nashville demigod Faron Young cut Willie’s melancholy classic “Hello Walls”; the immortal Patsy Cline did the terminally wistful “Crazy”; Billy Walker did the corrosively depressive “Funny, How Time Slips Away”; and Ray Price made a hit out of the anthem of hedonist fatalism, “Night Life” (“The night life ain’t a good life / But it’s my life”).

Soon, Willie himself became a legend of Nashville Nightlife: wild tales of excess in the whiskey, weed, and women departments began circulating about him. Some of them were true. There’s the one about the time he came in late from another woman’s bed and woke up to find that Martha had literally sewn him up into the bedsheets before pounding on him with a whiskey bottle. (Martha says this has been greatly exaggerated. She says she merely tied him up with jump ropes and beat him with a broomstick.)

Then there’s the time his second wife, Shirley, found out about Willie’s affair with Connie, the singer who would become his third wife, when Shirley accidentally opened the maternity bill for Connie’s child by Willie.

And there’s the one about the time in the ’70s when Willie—depressed at turning forty, loaded with liquor, and frustrated at the way the straitlaced Nashville music establishment had rejected his attempts to make the transition from songwriter to singer—stormed out of a bar and lay right in the middle of Music Row’s main drag, hoping a truck would run him over and put an end to his pain.

Willie’s songs are a gothic mirror of the wreck-strewn American emotional landscape.

Pain which drove him to quit the music business altogether at one point and become a pig farmer in a little burg outside Nashville—until even that went up in flames, when his little house on the hog farm burned to the ground.

A disaster which turned out to be the best thing that happened to him because it drove him back to Texas to take refuge, put him on the road again down there playing beer joints and honky-tonks and finding that everything Nashville disdained about him was loved in Texas. Where redneck cowboys and cosmic-cowboy hippies found in Willie’s wild and hairy outlaw persona the folk hero they’d been looking for.

By the late ’70s, the Austin-based Outlaw Music movement—which came to include other songwriter-rebels like Waylon Jennings and Kris Kristofferson—became a national phenomenon, and soon Willie Nelson became a Beloved National Figure, a fixture at Jimmy Carter’s White House, and an occasional movie star too. (In The Electric Horseman, he improvised the immortal line “I’m gonna get me a bottle of tequila and one of those little keno girls who can suck the chrome off a trailer hitch.” The autobiographical Honeysuckle Rose, the best of his starring roles, chronicled faithfully the way his unfaithful life on the road broke up his marriage to third wife Connie.)

By the ’80s, however, the Outlaw myth itself had become a bit, well, institutionalized, little more than a marketing device. Onetime rebels against the Nashville establishment, Willie and WayIon were now smiling Kewpie-doll-like wax figures in Nashville’s Country Music Hall of Fame; Willie had a big beach house in Malibu. By the end of the decade he’d settled down to start his fourth family, with live-in companion Annie D’Angelo, a makeup artist he met on the set of the TV remake of Stagecoach. (They got married on September 16 in Dallas.) The Outlaws were now rich and stable insiders, and some of their fans were beginning to wonder how much reality was left in the Outlaw Music and how much bullshit had crept in.

And while there was a lot of hype around him, if you ask me there’s something more than that to Willie Nelson, something that gets lost in all the good-timin’ shitkicker-chic mystique surrounding him. Two things actually: Willie as a writer who will ultimately be recognized not only as a colorful character but also as a figure worthy of rank among the classic American songwriters, someone whose brilliant self-lacerating sad songs transcend the country-music genre (we’re not talking about Randy Travis New Traditionalist pap here).

Second: Willie as a powerful unifying figure in the divisive racial culture of the South. Which brings us to a memorable kiss. A courageous kiss on the lips. Between two men.

Not exactly what you might be thinking, but it’s a kiss that’s become a kind of legend in country-music culture.

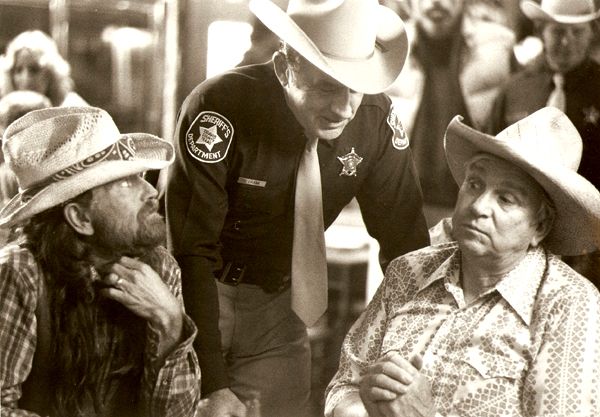

It took place back in 1966, at a time when Willie was struggling to make the transition from songwriter to performer. He had put together a package of acts which was going to tour as “The Willie Nelson Show,” and he wanted to include Charlie Pride, an up-and-coming country singer whose songs Willie admired but who was finding it tough getting gigs because he was black. Back then, the country-music scene, particularly in Texas and Louisiana, where “The Willie Nelson Show” was heading, was still hostile to any form of integration.

In fact, according to Willie, one of his closest friends, Dewey Grooms, the owner of the Longhorn Ballroom in Dallas, had proclaimed proudly that no black singer would ever take the stage at his honky-tonk. The way Willie tells me the story one night on the bus, heading to a gig at the Melody Ranch in Waco, Texas, he makes what happened next sound like it was just some spontaneous, whiskey-inspired happenstance, although I suspect there might have been more deliberation than he likes to let on.

“One day Charlie Pride went over to the Longhorn Ballroom to listen to a singer called Johnny Bush. Then Johnny called me and said Charlie was there in the audience. And so I went over and got onstage and introduced Charlie—called him up onstage.”

But Willie did more than give a stage blessing to the black singer: he sealed it with a kiss. “I kissed him on the mouth. And to make a long story short, before the night was over Dewey was over there hugging him, too. And we all wound up at the motel singing songs till ten the next morning, if I remember correctly. Dewey passed out drunk on the bed with Charlie. If I’d only had a camera …. ”

Not only was Willie’s kiss a brave personal gesture, it was brilliant theater (it’s doubtful the impact would have been the same if he’d merely put his arm around Charlie Pride). Word spread far and wide, the incident became an instant legend—and Pride became an accepted figure on the redneck honky-tonk circuit. Integration achieved in Willie’s own peculiar way—getting racial antagonists to pass out drunk on the same bed together—may not have the magisterial style of a Supreme Court decision, but it had a powerful effect on the unofficial social culture of the South.

What Willie had begun doing with that kiss was creating something that may be his most enduring contribution: a role model for the post-racist redneck. Mary McGrory once wrote, apropos of Jimmy Carter, that people up North insufficiently appreciate the courage and character it took for a white raised in the segregated South not to become a racist. At a crucial time in the late ’60s and early ’70s when it looked like George Wallace (if not the Klan) was going to be the voice, the embodiment, of the White South’s response to integration, Willie offered an alternative: you could wear shitkickers, cowboy hats, and Lone Star belt buckles, get drunk in honky-tonks, be the baddest good of boy you wanted to be, but hating black people didn’t have to be a part of it.

So he may owe a whole huge hell of a lot to the I.R.S. But we owe him too.

Jimmy Carter understood that. Which is why he made Willie a fixture in the White House, the good-natured Falstaff in an otherwise overly prim regime.

I asked Willie why he hadn’t been invited to the Bush White House—“Bush is a Texan, right?”

Willie raised his eyebrows slightly. “Where was he born?”

WHO’LL BUY HIS MEMORIES?

A garish South Texas sunset was streaking the sky over McAllen, Texas, when I caught up with the Honeysuckle Rose. It’s a massive supercruiser, all gleaming tensile alloy, that looks poised to spring even when it’s stationary. On the nearly windowless right flank is a delicate, pastel-colored mural of a desert sunset with a lone cowboy gazing into the cactus-stippled wasteland.

I’d found the bus parked in the rutted dirt lot behind a big old roadhouse called La Villa Real off Route 83. In a couple of hours, the full eight-member Willie Nelson and Family traveling band will take the stage for the first time since the I.R.S. anvil dropped on Willie’s head. Tonight’s the first night in a weeklong tour of honky-tonks and beer joints that will take Willie up to Billy Bob’s in the Fort Worth stockyards, down to Mudbugs in Gretna, Louisiana, then back to the Melody Ranch in Waco, and finally, after a stop at Willie’s homestead in the Hill Country outside Austin, north to Nashville for an appearance at a beer joint called Bubba’s Fuel Stop and a visit to his possessions on exhibit at the Willie Nelson museum.

Yes, he’s back on the road again, almost an outlaw again, just about the time the whole Outlaw Music myth had begun to seem a bit ossified. He’s doing this kind of tour for one obvious and one less-than-obvious reason. Obviously, he needs the money, every cent he can get. Even after the I.R.S. sold off a number of his properties at auction, he’s still $15 million in the hole, and he’s got a family with two young children to feed and no assets to his name except his voice and his guitar pick.

While film-and-music-business friends have offered to do benefits for him, and fans have taken up collections, he’s insisted he doesn’t want anything construed as charity: he wants to pay his I.R.S. dues on his own through his own efforts.

And he’s got a plan. A complicated two-part plan that involves a music partnership with the I.R.S. and a lawsuit against the people he claims got him in trouble in the first place. Willie’s quarrel, he says, is not really with the I.R.S. He’s not disputing the revenue service’s decision disallowing $6 million in deductions from investments in dubious shelters ten years ago, a sum which has grown to $15 million in penalties and interest (Willie’s paid all his taxes since then). His quarrel is with the people whose tax advice he relied on back then, and who made what he calls the “horrible, devastating mistake” of putting him into those shaky shelters in the first place. That’s the gravamen of his $45 million civil racketeering (RICO) lawsuit against his former accountants, the Oscar-famed Price Waterhouse firm.

It all comes down to paper cattle. Ironically for Willie, the last legatee of American cowboy romanticism, one of the two tax-loss devices that led to his downfall was the sad contemporary devolution of the “home on the range”: the tax shelter on the feedlot. According to Willie’s pending lawsuit, Price Waterhouse put him into a shelter which involved taking a deduction on feed purchases on December 31 of one year and beginning to make a profit on cattle fattened with that feed on January 1. Willie’s suit also alleges that Price Waterhouse irresponsibly advised him to invest in an even more complicated tax-loss scheme involving treasury-bill futures.

“At the time Price Waterhouse was advising Willie to go into the T-bill investment,” says Jay Goldberg, Willie’s New York attorney, “it knew or should have known that the promoter of the investment had been called before the I.R.S. to testify about the bona fides of it, and had taken the Fifth Amendment privilege 135 times. Any reasonable person would have recognized the nature of this scam. It amazes me that an entity as august as Price Waterhouse could not have recognized the minefield as it lay before him, protruding out of the sand.”

Willie, notoriously naive about money matters, relied on the accounting firm’s reassurance, says Goldberg, and stepped right onto the land mine. A Price Waterhouse spokesman declined to respond to the specifics of Goldberg’s Fifth Amendment charge, but stated that “Price Waterhouse discussed with Mr. Nelson and his advisers various tax shelters … and pointed out the risks involved … Mr. Nelson and his advisers made all of the decisions.”

Goldberg believes that if the I.R.S. lets the lawsuit go forward Willie can pay off a substantial portion of his tax bill with damages he’ll recoup from Price Waterhouse. “This could be enormous,” says Goldberg. “Another Texaco case.”

If the I.R.S. allows the lawsuit to go forward. Because the I.R.S. at first moved to “seize” the lawsuit, meaning to claim all potential income from it. Seizing the lawsuit would have given the I.R.S. the power to auction it to the highest bidder. Indeed, says Michael Berger, Goldberg’s partner on the case, “it might theoretically have been possible for Price Waterhouse, defendant in the suit, to buy it and thus quash it.”

This peculiar outcome was averted in late April, when Willie’s tax and business adviser, Laurence Goldfein, a former I.R.S. attorney now with Richard A. Eisner & Co., worked out what Goldfein calls “a creative, innovative arrangement” with the I.R.S. that put the Feds in the music business with Willie, and that will also, in effect, allow the I.R.S. to “fund” Willie’s lawsuit against Price Waterhouse. See, when the I.R.S. seized Willie’s recording studio, it took possession of scores of hours of tapes stashed therein. Included among them were some unique, unreleased tracks. The deal with the Feds allows Willie to make a limited number of albums from that stash. Seventy-five percent of the net proceeds will go directly to the I.R.S. to satisfy Willie’s debt, and 25 percent (up to $500,000) will go to Willie’s lawyers to finance vigorous pursuit of his civil racketeering case against Price Waterhouse.

“I went down to Dallas and convinced the I.R.S. there I was an animal,” Jay Goldberg tells me. In other words, that he’d prosecute the suit so aggressively that the I.R.S. would be better off funding it than trying to auction it off. Goldberg, who’s known for his successful defense of Bess Myerson’s boyfriend, Andy Capasso, and for his role as a self-proclaimed weapon of terror in the Trump divorce action (“I’m a killer,” he said while representing the Donald. “I can rip the skin off a body”), is convinced that the albums and the lawsuit will get Willie out of hock to the government and back on his feet.

But all of that is potential, down the line. Meanwhile, Willie needs cash to get from day to day. Of course, the few thousand he’ll clear from playing this tour of roadhouses can’t compare with what he could pull in from playing stadiums or Caesars Palace, as he has in the past. But he’s on the road playing the all-Bubba southern beer-joint circuit for something more than merely the money he’ll get from the gate—he’s out there to show the flag, get back close to the hard-core fans who made him a folk hero, show them he’s not the near-suicidal basket case the National Enquirer portrayed him as in a memorable front-page story, headlined WILLIE NELSON, HOMELESS AND BROKE. It’s important to him to prove that he’s still the same old Willie, alive and kickin’ in his shitkicker boots and red bandanna. Or, as the promotional T-shirt for his new cable Outlaw Music Channel proclaims, WHERE THERE’S A WILLIE, THERE’S A WAY.

And in fact, from what I saw, it looks like being forced to get back on the road by the I.R.S. crisis has been a kind of rebirth for him.

An even stronger indication of the rebirth is that he’s writing again, if only in his diary. For a long time he wrote almost nothing, with the exception of one mystical song called “Still Is Still Moving.” There was not enough discomfort and sadness to drive him to the page. Now he’s got more than enough, and he says he does plan to write songs again.

But not about the I.R.S. mess.

“You can’t put a melody to this shit,” he told me.

THE LOST VERSE, FOUND

It was not long after I boarded the Honeysuckle Rose down in McAllen, Texas, that I thought I might be hot on the trail of the Lost Plutonium songs. I thought I might actually be listening to them.

It’s close to midnight and I’m sitting across from Willie at a table in the cramped galley section of the bus (between his master bedroom in the back and the communal post-gig party going on in the forward compartment). I begin to edge into the subject of dangerously sad songs by asking Willie about a curious passage in his autobiography (Willie). One that seemed like it might be a veiled reference to the secret stash of songs. In the book, Willie describes a moment in his life, sometime in the early ’80s it seems, when he suddenly found sad songs were bringing him so low, eating his heart out, he had to give them up, renounce them altogether.

“I was taking myself to the bottom,” he wrote. ‘‘You sing those heartbroken, look-what-a-fool-I-am lyrics over and over, year after year, and you can find yourself believing life is truly like that and always will be.” It was a vicious cycle, he said, listening to the sad songs, which led to drinking, which led to getting into the kind of trouble that leads to singing more dangerously sad songs.

And so, he said, he made a major decision—to go cold turkey, to just say no to heartbreak songs. ‘‘If I get an idea for a negative song now, I reject it,” he wrote.

It turned out it wasn’t that easy. The ban on sad songs failed, he tells me, ‘‘because everything I write is sort of sad.”

Willie sometimes sounds bemused by his own penchant for sadness.

He started writing tragic love songs “as early as age twelve.” He even half recalls the words to one he wrote that year, a song with the gloomy title “The Storm Has Just Begun”:

Each night the raging storm clouds take away the stars above

Each day the same clouds take away the sun Uh, something, something and I realize The storm has just begun.

“That’s kind of looking on the dark side for a twelve-year-old kid,” I say.

“I had some real young girlfriends. So it wasn’t unusual for me to think about writing love songs. But to come up with the words that I did come up with at that early age was a little baffling. A little unusual for a kid.”

It wasn’t long, however, before life provided him with more than enough material for love-tragedy songs. His high-school sweetheart, his first true love, he says, died in a car crash. Life has not failed him since, in that sense.

And so, though he tried, he couldn’t stop writing sad songs completely. “But I started consciously trying to find a positive ending to a negative beginning. Pure hopelessness is not something I can write about a lot anymore.”

“But some of your most powerful songs come from that pure hopeless place, right?”

“When you feel hopeless you write that way,” he says. “Once you pass a certain point, hopefully, you won’t feel hopeless anymore.”

“You mean you have to get all the way down to the bottom in order to get back.”

“I think writers do,” he says. “Whether it’s true for anybody else … Redheaded people do, I know that.”

I ask if he thinks being redheaded—feeling like an outsider, different—shaped his sensibility.

He downplays the effect, although he admits he never liked his boyhood nickname, “Booger Red.” And then there’s his celebrated concept-album allegory, Red Headed Stranger, a song cycle about a preacher who finds destruction, then redemption, in his fall into carnality. “I have related to that story, that song,” Willie tells me. He concedes he too is a creature of extremes. “I go from brilliant to stupid. Not much in the middle there.”

But he does realize that there’s something unusual about the extremes to which he’ll take the remorse, regret, and self-laceration in his songs.

“I do seem to stretch it out,” he says. “Stretch it out in every direction as far as it will go. And then a little further.”

As if to illustrate, he says, “Let me play you something … ”

He searches through a stack of tapes heaped up on the galley table. Picks one out.

“This is a tape we’ve been working on, hope to get out soon,” he says.

It has a strange history, this tape, Willie tells me. It was made “a good number of years ago, down in a little recording studio in Bogalusa, Louisiana.” He’s vague about why it lay buried for so long, why it’s been unearthed now. My immediate intuition that this might in fact be the Lost Plutonium music is only reinforced when he feeds it into the deck and begins to play some selections from it.

Killer sad songs. Haunting, mournful, remorseful, unmerciful sad songs. One after the other. Listening to them I feel myself spiraling down; painful, long-buried memories of loss and disappointment suddenly stirring, lurching around the psyche, leaving blood on the tracks.

At one point, Willie seems to take pity on me. Puts on an up-tempo number. “This one will get you up off the floor,” he says, grinning. “Don’t want to leave you down there bleeding.”

“Bleeding is right. That was like open-heart surgery,” I say. “Without the anesthetic.”

“DeBakey don’t cut like that,” he says, picking up on the image.

“I’ve got some others in there that go pretty far in that direction. There’s one called ‘Your Memory Won’t Die in My Grave.’ Another happy tune,” he says, laughing. “Another little number designed to cheer you up.”

“ ‘Your Memory Won’t Die in My Grave.’ In other words, suffering and loss won’t even stop when you die?” I ask him, sensing a new, sadistic refinement in sad-song psychology. “What good is death if it doesn’t get rid of bad memories?” I ask.

“You thought it was gonna be that easy?”

“That’s pretty diabolical to suggest that even if you kill yourself you won’t get rid of the pain.”

“It’s a horrible thought,” Willie says with mock piety.

At this moment, probably the high point of the whole trip for me, Willie plays a song that has me almost certain that I’m hearing the Lost Plutonium tape, or at least the Ur-source of the legend about it.

He plays me a version of what many aficionados consider the quintessential Willie Nelson song, “Angel Flying Too Close to the Ground”—but a version that’s never been released before, a version with a Long-Lost Missing Verse.

“Angel” is a song that evokes far more passionate responses than almost any other song Willie’s written or sung, with the possible exceptions of “Crazy” and “Blue Eyes Crying in the Rain.” When he sang “Angel” at the roadhouses on this tour there was a kind of reverent, breathless silence, punctuated by strange yips and yelps, cries and whoops of simultaneous exultation and pain. Women swear it’s their story, and men swear it’s their story, or, anyway, the story of the woman who left them.

If you had not fallen

And I would not have found you ….

That fallen-angel image is powerful in a mysterious way. Willie says it came to him one day in Hawaii, out of the blue. He won’t say who it was, what special angel inspired it (although I think I later learned the answer from his sister, Bobbie), but its power transcends the particular source, conjuring up the bittersweetness we all feel about our hopelessly divided nature, tom between earth and sky. It’s Willie working on the same theme, if not exactly the same level, as Shakespeare in his “What a piece of work is a man” meditation—“how like an angel” and yet how earthbound too is “this quintessence of dust.”

As he switches the tape off, Willie tells me that what I heard was the first recording he ever made of “Angel,” and that this original version contains a verse that he’s never played or sung or recorded since then.

I ask him why.

He says something vague about maybe having forgotten. In any case, this is how the Lost Verse goes:

The time we spent together—

The blinking of an eye.

But time stands still

When love wants to be found.

The world we built together,

Still spinning in the air

For angels flying too close to the ground.

(As it turns out, at the last minute, Willie decided to unleash this dangerous sadness upon the world—but you have to know the password. The album advertised on late-night TV, entitled Who’ll Buy My Memories?—available to those who call 1-800-IRS-TAPE—is dangerous enough: heartbreakingly lovely songs with just Willie and his gut-string guitar. The New York Times reviewer called it “even wiser and sadder” and “more haunted than ever.” But what the Times didn’t note is that callers who order the album are then advised of the availability of an unadvertised tape, one called The Hungry Years, the tape Willie played for me on the bus, the one that contains the killer version of “Angel” with the Long-Lost Verse. In my view this is the real Lost Plutonium tape. Listen to it at your own risk.)

TORN BY THE LOVE OF TWO STRONG WOMEN

Sunday morning on the Hill, Briarcliff, Texas. I’m sitting on the back porch of Willie’s sister Bobbie’s house, overlooking the world Willie built. A world not so much spinning as gyrating back and forth, in and out of his hands. It’s Willie’s beloved Pedernales Country Club and the recording studio/office complex he built near the twelfth green, the perfect paradise on earth in the rolling wooded hills here in the heart of the heart of Texas. It’s the place that was the center of his creative and family life—cut some songs, slice some drives, and visit with friends and family who live in homes like Bobbie’s perched on the Hill above the fairways.

When the I.R.S. seized his other properties they were losses; when they seized this one they took his home. Left him feeling, if not homeless, then profoundly dispossessed.

Willie’s outlaw sex-symbol appeal has left a trail of Hollywood women and broken hearts.

We’ve just disembarked from the Honeysuckle Rose after a ten-hour ride through the rainy Louisiana night following the Mudbugs gig. I’m sipping coffee as Bobbie refills the feeders for the hummingbirds who visit the Hill on summer mornings like this. At sixty, Bobbie’s still a striking woman, a real prairie-goddess type with beautiful haunting eyes and luxuriant auburn hair that hangs down all the way to her knees when she hasn’t tucked it up inside her black ten-gallon hat. Bobbie, who plays keyboards with his group, has been making music with Willie for half a century now, since they entered church gospel-singing contests together as kids (“We always won,” she says proudly). Over the years she’s seen him at his worst, knows his fuck-ups and failings, the devil inside him. But she also sees the “angel flying too close to the ground.”

This morning Bobbie’s telling me about the effect the seizure of the Hill complex here had on her brother.

“I was worried about Willie for a while,” she says. “I really was.”

“In what way?”

“I mean, look at all this,” she says, gesturing down the fairways to the padlocked recording studio nestled in a clump of shade trees. “To have it all snatched away like that. But the worst thing about it was that they took his music. They didn’t take just material things, they took all the tapes in the studio. To lose that too … ”

Last night, after the gig, Willie had me almost convinced he was philosophical about the whole thing.

“I had time to prepare,” he said. “I knew this was coming down for several years.” As the appeals played themselves out, he got used to living with a fiscal Sword of Damocles hanging over his head, knowing someday it was going to fall and cut deep.

Still, when it finally did, it came as a shock. Willie says he’d been assured the I.R.S. wouldn’t suddenly swoop down and seize everything, leaving him homeless. “They figured if I had known about it I would have hid everything. But I did know about it and I didn’t hide nothing.”

I ask Bobbie if she felt there was any substance to the report in the National Enquirer that Willie had been scrawling suicide notes.

“Well, I know Willie doesn’t allow that kind of talk in his mind. Not for very long. But occasionally we do get … Willie … you know, he’s human. And, uh … if you just think about it … ” she says, trailing off.

“You know,” she resumes, “this is not the first time we lost all our worldly goods. We’re used to starting over again. We’ve been orphaned before.”

It happened first when they were still children. It wasn’t that their parents died, they just … slipped away. First, their mother, a restless soul by Bobbie’s account, ran off to start a new life on the West Coast. Then their father abandoned them to take to the road as a traveling musician. Willie and Bobbie were taken in by their paternal grandparents, who raised them “with a lot of love.” Both mother and father would reappear periodically for visits, but still, says Bobbie, it felt like “being orphaned.”

A bit later, as Bobbie is showing me some Nelson-family pictures on the wall of her foyer, I’m struck by one black-and-white blown-up snapshot in particular: a beautiful woman in a stylishly cut ’40s-era suit, looking a bit like Ava Gardner in her prime, only more mischievous, playful. In fact, she’s flashing the camera an incredibly wicked, sexy grin.

“Wow, who’s she?” I ask. “That’s Myrle,” she says, “our mother.”

“Men must have been crazy about her.”

“Oh yes,” Bobbie says matter-of-factly. “She drove them wild.”

“Willie’s really got her eyes.”

“That’s it,” she says. “They were two of a kind. God, did she love Willie! She idolized him, just idolized him. And she was very jealous.”

“What do you mean, jealous?”

Bobbie explains the painful tug-of-war that was fought over the two of them throughout their childhood. Willie loved the grandmother who raised him, but there would be periodic visitations from his wayward mother, Myrle, who would blow in from the West Coast, win back pride of place in Willie’s heart—and then leave him. Bobbie recalls how she and Willie would stand there crying, hopelessly heartbroken, watching Myrle’s car disappear in the distance.

Or as Bobbie puts it—in her pure stark prairie-goddess way—“Willie was always torn apart, torn by the love of two strong women.”

As she points out, this is a powerful, recurrent theme in his most emotional songs, most explicitly in the haunting “Why Do I Have to Choose?” Indeed, she says, there’s a lethally sad song on the Bogalusa tapes called “She Is Gone,” which seems on the surface to be about a romantic loss, but which was, in fact, written shortly after his mother died. She was the original Angel Flying Too Close to the Ground.

WILLIE GOES TO WILLIE WORLD

That afternoon on Highway 31 on the way to the Willie Nelson museum, Willie was telling me about the positive side of his tax disaster. About the way the farmer groups, who remembered the way he’d saved family farms with his Farm Aid concerts, stepped in to stop the auction of one of his oldest family properties in Texas, until they could get together the funds to buy it and hold it in trust for him. About the way friends called up and offered to do free concerts for him. And about the tens of thousands of fans who wrote in, sent dollar bills, and cheered him on in the beer joints he played.

“It’s an amazing feeling to have people that you never dreamed would give you a second thought turn out to really care. A lot of people could have said, ‘The son of a bitch ought to pay his taxes’—as I told you I paid my taxes—but a lot of people didn’t even think that at all. They immediately said, ‘Well, what can we do to help?’ And that’s gratifying, particularly since a lot of support’s come from guys who are still struggling themselves to make a bad buck in a bad world.”

Losing title to his beloved Pedernales home hurt Willie, but as for the loss of his personal possessions … surprisingly, he says he doesn’t even want them back. He says he’s happy to leave them on exhibit in the museum in Nashville, where he and his fans can visit them. Willie insists he’s content to start over with no possessions at all.

Of course, he’s never been a materialistic rhinestone cowboy; he still wears ratty old corduroys and giveaway T-shirts, along with his trademark red bandanna. The best proof of his lack of interest in expensive objects came one night on the bus when Willie and one of his buddies got into an inconclusive discussion as to “what’s worth more, an ounce of diamonds or an ounce of gold.” Neither had the slightest idea. Willie seemed to know or care as little about the subject as your average Trappist monk.

Still, the items seized by the I.R.S. from his recording-studio office were more than mere valuables—they were, as his song goes, pieces of his life.

“Are you sure you won’t want them back sometime?” I ask him. “I won’t hold you to it, or quote you saying you don’t want them back, in case you change your mind.”

“No,” he says, the loss of everything has caused him to change his attitude toward all possessions. “When you really start evaluating things and looking at material things against loved ones and things that matter, then the material things lose value, they’re just things. I started seeing that and I started thinking that way and I’m glad I did,” he says, “or else I’d be real negative about the whole thing and it wouldn’t have done a damn bit of good.”

At first I wasn’t sure which of Willie’s categories this philosophical renunciation fell into—the real, the bullshit, or the real bullshit—until I saw him visit his lost possessions at the Willie Nelson museum.

“Museum” in Nashville is a loose term for establishments that range from little mom-and-pop-run souvenir stores to big-time theme-park entertainment complexes like Twitty City, built by Conway Twitty, one of the many demigods in the country-music pantheon, who’s little more than a trivia question to the national culture. Willie’s “museum” is located just down the road from Twitty City (always wanted to use that phrase, “just down the road from Twitty City”) in a kind of mall of country-star museums called Music Village.

For a long time it was on the mom-and-pop-shop end of the spectrum (it’s run by sincere, dedicated Willie Nelson fan couple Frank and Jeanie Oakley). In fact, until the I.R.S. trouble, Willie’s memorabilia didn’t even fill up the square footage of museum space. (In part because he doesn’t wear rhinestone-spangled costumes, there are no rows on rows of glass cases with glittering jackets on mannequins, the staple of most other country-star museums.) They had to fill up the empty space with mini-showcases devoted to Patsy Cline and J. D. Sumner, who, as you all know, was a backup singer for Elvis and author of the memorial-tribute song, “Elvis Has Left the Building.”

But suddenly the Willie Nelson museum has more memorabilia than it can handle. It looks like tons of the stuff are still spilling out of crates in the huge storeroom of the museum, part of the truckloads of knickknacks the museum bought from the I.R.S. Just yesterday, they opened up the brand-new Willie World section of the museum, featuring a perfect re-creation of Willie’s main working base—his recording-studio office. And today, for the first time, Willie’s paying a visit to all the possessions he hasn’t seen for six months.

Willie Nelson comes to the Willie Nelson museum—it is a memorably absurdist moment. Willie’s reaction to the whole thing is curious. He gives his desk, the display of gold records, even the bronzed baby shoes little more than a bemused glance. Instead, he steps over the velvet rope and makes a beeline for his dominoes table.

“This is the real southern game,” Willie tells me as he sits down, fans the tiles, and starts passing them out to his pal Larry Trader and a tour guide named Chico. Willie’s been a demon for dominoes all his life, and soon he and the others are deeply absorbed in slapping down tiles and muttering obscene imprecations at each other’s play.

So intent is he on the game, in fact, that he doesn’t seem to notice that a small knot of tourists has wandered into the Willie World area. They’re standing behind the maroon velvet ropes, gazing at Willie’s office and ... is that Willie?

You can see from the looks on their faces what’s going through their minds: That guy playing dominoes, he sure looks like Willie Nelson. Is he, uh, on exhibit in his own museum, like a live animal in a zoo? No, couldn’t be. Maybe they’ve got a Willie look-alike to add to the realism of the exhibit. A mechanical dominoes-playing Willie? Or maybe it is the real Willie—he’s so broke he’s reduced to earning money posing as himself?

Willie, for his part, must have finally noticed the attention but kept his eyes on the dominoes, didn’t break character. Continued playing several games, in fact, and after a while the visitors wandered off to view the glass cases with the costumes and the shrine to Elvis’s sideman.

I thought this was a little strange at the time. (Usually he’s happy to greet fans and sign autographs.) It wasn’t till later that I realized what was going on. And how sad it was. As long as Willie kept himself immersed in the dominoes game he could sustain that momentary illusion that nothing had changed, nothing was different from the way it had been when he played the game in these exact same surroundings back home in Texas before the I.R.S. nightmare. As if he were back there again. As if the nightmare never happened. The moment he had to look up and acknowledge the velvet ropes and the tourists, the fact that he was not enjoying his home life, that he was playing himself in an exhibit of his home life, the spell would be broken. And he’d have to experience the sadness of his dispossession all over again.

[Photo Credit: Bert Cash]