It took me a while to figure out that to buy a book was to vote for it. I get it now: if I like a book or a writer, I speak with my wallet. I end up with some wonderful books, of course, but I also get to telegraph my values to the impressionable publishing business. (I borrow bestsellers and the books of dead authors from the library and I share CDs, but I always buy the works of living poets and literary novelists.) And if I really love a book or the writer’s a friend, I double down, triple down, go for the fairy godmother crown; I buy all I can afford, and give the extras away. Is there a better present than an autographed book? My house is crumbling and there’s green stuff growing on the walls, but I don’t care; I’ve chosen to be rich in books.

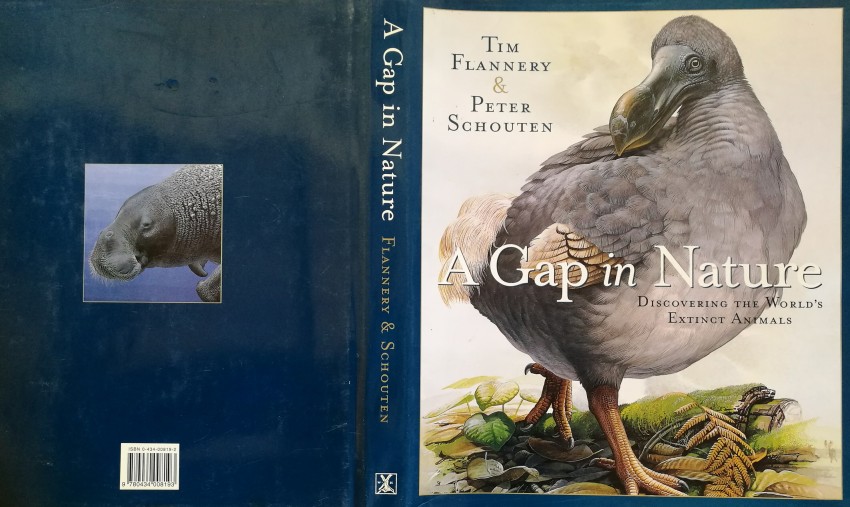

I discovered my favorite gift book deep in Bill Bryson’s A Short History of Nearly Everything. Bryson called it “the most complete—and it must be said, moving—catalog of animal extinctions from the last three hundred years.” A Gap in Nature is a coffee table book, delicately beautiful and lovingly published, the collaboration between two Australians, science writer Tim Flannery and wildlife illustrator Peter Schouten. Their quest was to track down lost species, however they have been preserved and remembered (a stuffed skin, illustration, journal description), then conjure them in words and drawings.

Some extinct creatures are permanently elusive, like the big beautiful flightless birds described by a castaway and gone by the time anyone else thought to look. Others have been pieced together from incomplete evidence, like the dodo that graces the cover, the big dumb bird that had no experience with humans and was all too happy to cooperate with its hunters. Soon there were no dodos. Before long, there weren’t any dead dodos, either; the last stuffed dodo began to grow mold and was thrown on a trash heap and set afire. Hold it, guys—we’re frying the last stuffed dodo in the universe! “Someone rescued the head and a leg from the flames, and these are now the most solid testimony the world has that this bizarre bird ever existed,” Flannery writes. A scorched head and leg—what a trophy. Schouten has cleaned up the bird for his portrait, though, and filled in the rest of his body, and like all the subjects in this book—Steller’s sea cow, the terror skink, the red-moustached fruit-dove, the laughing owl—the dodo looks dignified, slightly melancholy, and incandescent. (He’s also one of the few subjects of this book whose extinction occurred more than three hundred years ago.)

It’s a gallery of a vanished world, the perfect book to curl up with by a winter’s fire, and full of poetic moments (the laughing owl, for instance, liked to be held by humans and could be called from the forest by accordion music). It’s the kind of quixotic book we need more of. I don’t want it to become extinct; I want it to stay in print as long as there are humans to appreciate it, so I vote for it. I buy it often. It’s the best present I ever gave a science teacher, next to the Darwin finger puppet.