“I had meant to time the closing of the door with a subtle emission of a fart,” my guru said as he pulled shut the door to his room at the Holiday Inn in Oxford, Mississippi. “Evidently my timing was off.”

He was being “Will Campbell” today. You could tell by his outfit—his cheap black preaching suit and the wide-brimmed Amish hat that capped a freckled dome and a riotously unbarbered fringe of gray hair. On his feet were a pair of rather pricey alligator boots, which had been given to him by his closest friend, the country songwriter and singer Tom T. Hall. In one hand, Campbell carried his staff—a hand-carved cherrywood cane—and in the other a plastic glass to spit tobacco in. A maid in the parking lot gave him the sideways sizing up such a metaphorically mixed outfit demanded.

As a matter of fact, I was a little suspicious of him as well. Who was this fellow Will Campbell anyway? Some called him the conscience of the South, a kind of white Martin Luther King Jr., and yet he was one of the most profane and wickedly funny men I’d ever known. Considered by many to be among the most original and radical thinkers in America, he is seen by others as little more than a whiskey-swilling gadfly and spiritual provocateur. A poor son of the Mississippi soil who studied theology at Yale, Campbell returned home to become a legend in the civil rights movement, then alienated many of his fervent admirers by turning his ministry toward the Ku Klux Klan. He ministers to the poor, the dispossessed and the unknown, but he is idolized by the rich, the powerful and the famous. His life and work are studied in colleges and seminaries across the country; he has been compared on occasion to Jeremiah or Hosea or even a modern-day Jesus, and yet Campbell himself admits that in all these years, “I can’t point out one thing I’ve actually personally accomplished.” He is a preacher without a church, a Southern Baptist who is detested by the leaders of his own denomination. He is, in short, an assemblage of rude contradictions, a man not easily loved or understood and impossible to dismiss.

At this particular moment the Sage of the South had hold of a plastic dry-cleaning bag, about five feet long. He knocked on the door next to his and handed it to the man who answered—Campbell’s biographer, Tom Connelly, a distinguished Civil War historian from the University of South Carolina.

“Connelly, I want you to dispose of this for me,” Campbell said imperiously.

“What is it?” the white-haired professor inquired.

“What the hell do you think? It’s one of my condoms. I think it’s time we started practicing safe sex.”

I had followed Will Campbell to Oxford because for twenty years he had been an unresolved enigma in my life—since the day he had wandered into my office at the Race Relations Reporter, in Nashville, Tennessee. It was my first day on the job. Campbell announced that he needed a haircut. I had no idea that one of the most controversial figures in the civil rights movement, which was supposed to be my beat had just plopped himself into my office chair. Such was my confusion that I wasn’t certain whether cutting hair was a part of my job description. Of course, as soon as he took off his hat I could see that nature had already done most of the work.

Like many young writers in the South at the time, I idolized Campbell for having been right at a time when being right was dangerous. He had been the only white man at the creation of Martin Luther King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference in 1957; later that year, in Little Rock Arkansas, he had walked hand in hand with the nine black children through the cordon of National Guardsmen and the raging mob in that first, failed attempt to desegregate Central High. Wherever the races came in conflict, Campbell was quietly there counseling the demonstrators at the lunch-counter sit-ins, ministering to the Freedom Riders, consoling the mothers of the children murdered in the Birmingham, Alabama, church bombings—moving through the turbulent South with a small leather suitcase, a bottle of his sour-mash ‘medicine” and his old Gibson guitar slung over his shoulder.

“He was a walking nerve center,” says David Halberstam, who was a young reporter in Mississippi when he first noticed the slightly built white man always on the edge of events, at the shoulders of black leaders and white power brokers, whispering his message of radical change but also of the power of love, forgiveness and reconciliation. “He was enormously important but so deft and nimble that the reactionaries never caught on to him. His fingers were everywhere, but when you looked around—there were no fingerprints. He was the Invisible Man.”

“We are all bastards, but God loves us anyway.”

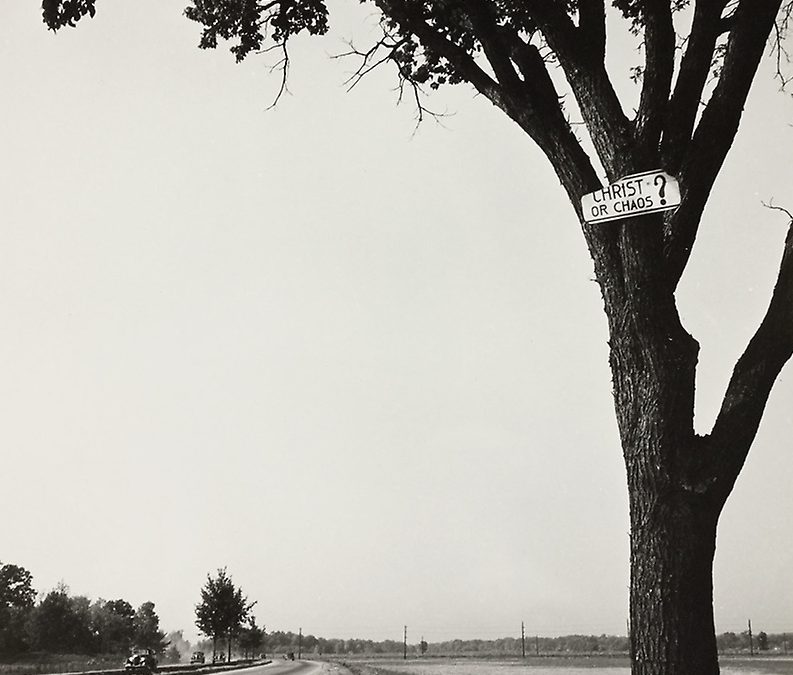

Gradually, legends grew up around Campbell concerning his vast influence, his talent for being a dozen places at once and his unconventional, unchurched religious beliefs. The main plank in his theological platform was “We’re all bastards, but God loves us anyway.” This single, radicalizing axiom would lead Campbell to begin his solitary and controversial ministry to the Ku Klux Klan.

“I have seen and known the resentment of the racist, his hostility, his frustration, his need for someone upon whom to lay blame and to punish,” Campbell wrote in his first book, Race and the Renewal of the Church. “With the same love that it is commanded to shower upon the innocent victim of his frustration and hostility, the church must love the racist.” Therefore, in 1969, on the night before Bob Jones, the Grand Dragon of the North Carolina KKK was shipped off to federal prison in Danbury, Connecticut, for contempt of Congress, Campbell was there in the Dragon’s Den to celebrate communion with a bottle of bourbon. Later, Campbell talked with James Earl Ray, the man who had murdered Campbell’s friend Martin Luther King. When people asked if he really expected to save the souls of such men, Campbell allowed that that would be presumptuous: “They might, however, save mine.”

I did not know Campbell well during my brief tenure in Nashville, and after I left there in 1971, I saw him only once more, performing a wedding in Atlanta. Back then, I thought Campbell had the moral authority to become the spiritual voice of our time, but as the civil rights movement faded from public consciousness (and from my own), Campbell’s legend faded as well. Through mutual friends, I kept up with his peregrinations through the still-seething South. I heard about his ongoing campaign against the death penalty. I also knew that he had been taken up by the country-music establishment in Nashville as a sort of unofficial chaplain. He made a literary splash in 1977 with the appearance of his extraordinary memoir, Brother to a Dragonfly, about his relationship with his doomed elder brother, which was nominated for the National Book Award. His subsequent books and novels received less attention. I assumed that whatever Campbell had meant to me twenty years before had been a part of an ancient reality. Perhaps he had just been a creature of a particular historical moment, and now his time had passed. When a mutual friend of ours, Doug Marlette, the Pulitzer Prize-winning cartoonist for New York Newsday, appropriated the Campbell persona for a character named the Reverend Will B. Dunn in his cartoon strip Kudzu, it seemed to me that the culture had absorbed even this most indigestible morsel and rolled on.

Campbell had ridden into Oxford along with Tom T. Hall, author Alex Haley and half a dozen other eminent writers, poets and scholars who constitute a Southern literary gang informally known as the Brotherhood. They all had come down from Nashville on Hall’s tour bus, which was graced with a portrait of Hall’s idol, General George Patton. This evening members of the Brotherhood were scheduled to read and perform at a benefit for the Mississippi branch of the American Civil Liberties Union.

“Tom, we’re gonna run out to the campus before the show,” Campbell called out to Hall, who is a burly man with massive features and intelligent gray-blue eyes that seem about to pop out of their sockets from the stress of containing his tireless mental combustion.

“Suppose I come along,” said Hall.

“Well, come on, then.”

It was in Oxford that the Campbell myth had begun. “I came out here to be university chaplain in 1954, about three months after the Supreme Court decision outlawing segregation in public education,” Campbell said as we swung onto the campus. “I thought at the time that I would spend the rest of my life in Oxford. I guess I lasted a little over two years.”

Here, in the white-hot center of resistance to integration, Campbell discovered himself as that most despised creature of the Southern racial landscape: the nigger lover. Because he was a preacher, Campbell may have been spared some of the physical punishment inflicted on white integrationists—although the message was delivered to him quite pointedly after he had been observed playing ping-pong with a black minister at the YMCA. Days later, Campbell found his lawn covered with ping-pong balls painted half white and half black The dean of student personnel told him that he would have to consider where he was and to “adjust” his thinking appropriately.

“And then, by God, we were having a reception for new students, out here on the back gallery,” Campbell said as he walked outside the antebellum building that had once housed his office. “The dean was present. One of the assistant chaplains pulled me aside and said ‘Will, I think somebody put something in the punch.’ I went over and looked in the punch bowl, and sure enough, there were two human turds covered with what appeared to be powdered sugar. I said to the dean that I find it rather difficult to ‘adjust’ to fecal punch.”

Campbell was subdued on the ride back to the motel. This retracing of his early days had left him curiously empty. It was as if he had left some part of himself behind. When we got back to the Holiday Inn the other members of the Brotherhood were all gathered in a single room drinking whiskey and watching a basketball game. “Where’ve you guys been?” one of them hollered.

Tom T. poured a drink. “Aw, we went out to see where Will Campbell’s buried,” he said.

It was Saturday night at Gass’s store, a roadside juke joint in Mount Juliet, Tennessee, where Campbell makes his home. The house band was playing some standard country tunes. Kitty Wells’s pretty granddaughter was on the drums. This is as close to being Campbell’s church as any place is likely to be. There is a powerful sense of tradition and community in this dark little nightery with its neon icons in the names of Miller and Bud. Will married nearly half the people in this room,’ his wife, Brenda, remarked as we sat down. “Some he had to marry several times.”

According to Campbell’s friends, Brenda is the one person in the world he’s truly afraid of. They have a charming, playful relationship that has survived forty-four years of marriage, the raising of three children and an endless stream of needy and troubled people at their door. Since the beginning of their relationship, Brenda has handled the family finance; doling out a meager allowance to her husband, who believes that money is “evil.” Brenda also mows the lawn, a fact that early in their marriage contributed to the charge that Campbell was henpecked. The preacher at the little church he grew up in held special prayers for their marriage. “I went from being henpecked to being a liberated husband in a single generation,” Campbell joked.

“I thought it was the love of money that was supposed to be evil, not money itself,” I said.

“I know that’s what the Bible says,” said Campbell. “But I do think that evil is a greater problem for wealthy people. Now, the opposite is not true—I don’t think the poor are virtuous. I know plenty of poor folks who’d blow your sweetbreads right through your ear lobes.”

Campbell calls himself a “bootleg preacher,” which in his lexicon means that he conducts his ministry outside the traditional church. For him, the church is a human institution, not a divine one, and such creations are inherently evil. “No institution can be trusted, including the institutional church,” says Campbell. “They are all after our souls—all of them.” What institutions actually institute, he contends, “is inhumanity, by advancing the illusion that form is substance, the means are the meaning, doing is being, procedure is redemption—and so they can only further dehumanize relations between those they were instituted to reconcile.”

“He prefers the mythologizing because it keeps you from getting at the truth. The truth for him is too personal. It’s almost as if he has to put on a persona in order to be real.”

Until the mid-Seventies, Campbell was supported by a highly informal organization called the Committee of Southern Churchmen. Since then he’s made his living from writing and farming and lecturing (he speaks frequently at universities and religious gatherings). And having turned sixty-five last year, he draws Social Security. Although he will not serve on juries, Campbell does vote and pay his taxes. So one could not say that he is entirely independent of the grip of institutions himself.

“Institutions are inevitable, I know that,” he says. “I work within them all the time—I don’t claim not to. What I’m saying is, let’s not worship the institution. They are all basically self-loving and self-perpetuating. They are trying to make you over into their own image—it doesn’t matter if it’s Yale or Bob Jones University. They all have a line. What I try to say is that I may be working within this particular institution, but I don’t trust you. Anyway, that’s my story, and I’m sticking to it.”

He does not like to be called the Reverend Campbell because “it sounds condescending and a bit imperialistic. Some people call me a counselor,” Campbell says, “but it’s such an arrogant concept—like I can do something better for you than you can do for yourself. I’m not a reverend, and I’m not a counselor. I’m just a preacher.” Even the word ministry gives him trouble. “I don’t really have a ministry,” he insists. “I have a life.”

A few years ago, Campbell was invited to make a speech at New York’s prestigious Riverside Church on the subject of what the church could do to improve race relations in the city—a matter of profound interest at Riverside, which happens to be situated at the edge of Harlem. Campbell climbed into the nine-ton pulpit of sculpted limestone. He stood there dwarfed by the towering nave and the gleaming organ pipes. “I’ve been invited to enough of these affairs by now to know what you mean,” Campbell began in his twangy Tennessee drawl. “What you mean is ‘How can we improve race relations in New York City?’ ”—and at this point he paused significantly, casting his eye over the magnificent stained glass, the opulent icons, the velvet-padded mahogany pews, all paid for with Rockefeller millions—“‘and keep all this!’ ” His own modest solution was to hold a giant auction, give the proceeds to the poor and disperse the congregation to evangelize the world in the name of Jesus. “Surprisingly,” Campbell says, “they did not act on my proposal.”

Campbell left us at the table in Gass’s to greet some of his friends, trade some kind words with a waitress who’d had some recent sadness and share a drink and a couple of stories with some fellows in a booth. “Will just sort of ambles around, so sometimes you forget he’s at work,” Tom T. Hall had warned me. “I recall when a couple of students from a seminary came down and spent a whole day asking Will all sorts of questions. Then when they got ready to leave, one of them said, ‘By the way, Reverend Campbell, what do you do?’ ‘Oh, nothing,’ he said. But here he had been counseling them all day long, and it didn’t even dawn on them that this is what he did.”

When he is not on the road giving a speech or marrying or burying, Campbell spends his days on a forty-acre farm, planting hot peppers and tomatoes, or sitting in his log cabin office behind his house, pecking out sermons and books and talking to people in need. “I never do anything big,” he says. “It’s a series of little things, like helping people to read, holding a man’s hand who’s dying, singing a few songs to a fellow who’s about to go to jail.” Each year hundreds of people seek him out. They may be famous singers fighting a drug problem, ex-cons just off the road gang, young couples trying to reconcile a failing marriage—somehow they all find their way to the little cabin behind the apple tree in the hollow of the Stones River valley where Campbell conducts his business of “just trying to survive as a human being and not as some technological robot.”

“You love one, you got to love ’em all,” Campbell said.

“Bull,” said Brenda.

He cannot even pass a ringing public phone in an airport without answering it. “Because it might be someone in trouble?” I asked. “Oh, no!” Campbell replied. “Might be someone I want to talk to.”

Whom he does not want to talk to are the innumerable acolytes who show up on his doorstep with a copy of one of his books in hand, saying they want to sit at knee. “Well, tough shit” Campbell tells them. “I don’t want any disciples. I’m trying to be a disciple. I look and see a bunch of people following me and I fall to pieces.”

“Which is,” Campbell told his biographer, Tom Connelly, “the distinction between being a guru or a cult figure and not being one of those things. The guru says ‘Yes, come on down. We have this program, and we’ll put you work.’ I’ve never done that. It’s dangerous. Soon you start believing that shit.”

Once a priest in New Jersey phoned Campbell and said he wanted to come down South and join Campbell’s ministry because he felt called to do something important with his life.

“Where are you now?” Campbell asked.

“I’m at a pay phone in Newark,” the priest replied.

“Is it one of those glass booths?”

“Yes, it is,” said the puzzled priest.

“Are there any people out there, or are the streets deserted?”

“There are lots of people.”

“Well, son,” said Campbell, “that’s your ministry. Go to it.”

Campbell never keeps correspondence or papers of the sort that biographers and university collections hunger for. His former secretary Andy Lipscomb once discovered a pile of Campbell’s sermons moldering in the compost heap. When he reproved his boss for destroying such valuable records, Campbell observed that “bullshit makes the cabbage grow.”

He will not be lionized. Sometimes he purposely subverts himself—as at Duke University, where he was appointed “theologian in residence” for part of a term. To many of the students and faculty there, Campbell was virtually a mythic hero, and yet when he gave his main address in Page Auditorium, he suddenly folded up speech after two pages, said, “That’s it” and walked off the podium—leaving many of his supporters wondering why he had bothered to come. Doug Marlette had a similar experience when he was a Nieman Fellow at Harvard and invited Campbell to speak to the other fellows. “They didn’t get him at all, and Will didn’t bother to explain himself,” says Marlette. “He was excruciatingly inappropriate.”

Other times Campbell will be so incendiary he almost invites people to loathe him. He has on more than one occasion told a university audience that “this institution right here”—meaning Ohio State or Georgia Tech or whatever school he happens to be visiting – “has contributed, wittingly or not, to incomparably more bloodshed and misery, done more to maim and murder, than the whole lot of poor old country boys in sheets holding cross burnings in rented cow pastures. Now then, the Klan may be more bigoted than the ‘children of the light.’ But they’re not more racist. Racism is in the structures, the system in which we are all bound up. We’re all basically of a Klan mentality when it comes to our own structures and our own institutions.”

He was a preacher and a devout believer, but Campbell claims he was not really a Christian until his friend Jonathan Daniel was murdered in 1966. Daniel was a young theology student from the Episcopal seminary in Cambridge, Massachusetts, who had gone down to Lowndes County, Alabama, to register blacks to vote. He had walked into a country store with a white priest and two black friends, and when he came outside with a Moon Pie and a soda pop, he was shotgunned into eternity by a sheriff’s deputy named Thomas Coleman.

“What I like most about Will is that he does not divide the world into us versus them.”

Campbell got the news of Daniel’s death while he was visiting his friend P.D. East, the colorful and defiant editor of the Petal, Mississippi, newspaper called The Petal Paper. It was East, years before, who had badgered Campbell into giving him a definition of the Christian message in ten words or less. “We’re all bastards, but God loves us anyway,” East recalled. “Let’s see if your definition of faith can stand the test. Was Jonathan a bastard?”

Campbell was still in shock and deeply grieving for his friend. Mainly to get East to shut up, Campbell admitted that Jonathan was a bastard.

“Was Thomas a bastard?” East asked.

It was easy enough to agree to that.

Then East pulled his chair around, put his bony hand on Campbell’s knee and, staring directly into Campbell glistening eyes, whispered, “Which one of these two bastards do you think God loves most?”

It was the turning point of Campbell’s life. “Suddenly everything became clear,” he recalls in Brother to a Dragonfly. “I walked across the room and opened the blind, staring directly into the glare of the street light. And I began to whimper. But the crying was interspersed with laughter.”

He was laughing at himself: “At twenty years of a ministry which had become, without my realizing it, a ministry of liberal sophistication. An attempted negation of Jesus, (a ministry) of human engineering, of riding the coattails of Caesar … of looking to government to make and verify and authenticate our morality, of worshipping at the shrine of enlightenment and academia, of making an idol of the Supreme Court, a theology of law and order and of denying not only the Faith I professed to hold but my history and my people—the Thomas Colemans.”

“What I like most about Will is that he does not divide the world into us versus them,” says the black scholar and writer Julius Lester, a longtime Campbell watcher. “It’s that quality that enables him to really startle people. His whole object is to affect the soul of the other, and he does that better and more directly than anyone I’ve ever seen.”

A hazardous example of that occurred during the Sixties at a radical student forum in Atlanta. Campbell simply announced: “My name is Will Campbell. I’m a Baptist preacher. I’m a native or Mississippi. And I’m pro-Klansman because I’m pro-human being. Now, that’s my speech. If anyone has any questions I will be glad to try to answer them.” Pandemonium followed. “1 had intended to start a dialogue, maybe even a heated dialogue,” Campbell recalls. “I had not intended to start a riot.” He might have explained that pro-Klansman did not mean the same as pro-Klan in his vocabulary, the one having to do with the individual, the other with ideology. The blacks in the audience stormed out en masse, followed by half the whites. Those who remained were so abusive Campbell was afraid they were going to storm the stage and pluck his limbs from his torso. Half an hour later, when the crowd finally settled down enough for Campbell to speak again, he pointed out that just four words—“pro-Klansman Mississippi Baptist preacher” coupled with his own whiteness, had turned the students into everything they thought the Klan to be—hostile, frustrated, angry, violent and irrational.

Why does he do this? Why will he deliberately puncture the esteem people feel for him and even court their hatred, rather than accept the love and admiration and even the idolatry that attends even the most ordinary preacher in the high-steepled church? It would have taken very little for Campbell to have become a kind of media saint or a TV evangelist on the order of Swaggart or Falwell—the “electronic soul molesters” as Campbell calls them. He had tasted that power as a young man, still in his teens, at Louisiana College, a Baptist academy in Pineville, when he and his future wife, Brenda Fisher, would travel through the Catholic parishes in a rattletrap mission bus, stopping at every crossroads hamlet. Brenda would pump out “Bringing in the Sheaves” on the field organ while Campbell delivered his searing message of fundamentalist Christianity.

“Yeah, I used to be a street-corner preacher,” Campbell recalled as he returned to what was left of his now cold Gass’s pizza, “with my Bible in one hand and a microphone in the other. There was a great sense of power. My voice would be booming out through four loudspeakers, and I’d be strutting around, swishing the microphone cord. One time the power went off and I just kept on preaching; I couldn’t stop—it was a form of homiletic masturbation.”

“Friends and neighbors, you all know Preacher Campbell,” I suddenly heard the heavy-lidded bandleader say to the crowd in the bar. “Let’s give him a hand and see if he’ll bless us with a song.”

Campbell popped eagerly onto the stage. The band struck up “Rednecks, White Socks and Blue Ribbon Beer,” which has become a virtual anthem for Campbell whenever he’s at Gass’s. I had seen Campbell sing before, in his kitchen, hugging his old Gibson in his lap, or in a church when he had some theological point to make during a sermon and a song just seemed to say it better. On those occasions Campbell had a sly and in some respects passive way of delivering his music. His baritone voice is true but thin and wavery. Here at Gass’s, however, standing under the spotlight, with the microphone in his hand, there was a surprising transformation. He let loose something raw and confident and exceedingly indulgent “No, we don’t fit in with that white-collar crowd,” Campbell sang, as the crowd whooped with identification. “We’re a little too rowdy and a little too loud/But there’s no place that I’d rather be than right here/With my red neck, white socks and Blue Ribbon beer.”

At last for about five minutes in this shadowy saloon in the middle of a Tennessee nowhere, on a Saturday night in the Church of Miller Lite, Zen Master Campbell was giving the people what they wanted to hear.

“Sure I wanted to be a country singer—long before I decided to be a preacher,” Campbell says. “Country music is people music—honest, liberal and the only true American art form. It is also theologically sound.” The songs he chooses to sing speak of the hurt and hopelessness of a lonely woman becoming an alcoholic, or an anguished father waiting for his son to come home from the war in a box, or a murderous lover in jail. In Campbell’s view, each of them testifies to the message of 2 Corinthians, Chapter 5: “God was in Christ, reconciling the world unto himself, no longer holding men’s misdeeds against them and has committed to us this word of reconciliation.”

“Reconciliation!” Campbell will thunder whenever he quotes this passage. “Reconciliation to our own natures—it’s a hard idea to accept, and that’s why the gospel’s a whole lot more drastic than most folks have ever dreamed. Our trespasses are not held against us, we’re already forgiven. Don’t you see how that liberates us all? Black, white, Kluxer, preacher, banker, teamster, murderer, chairman of General Motors, head of the Ford Foundation—we are all bastards, but God loves us anyway.”

This message has had a special appeal for the “outlaw” element of country music—Willie Nelson, Johnny Cash and particularly Waylon Jennings. “I’m really anti-preacher,” says Jennings, who grew up in the Church of Christ and once aspired to be a preacher himself, “but Will Campbell is one of the few people in the world I believe to be completely sincere. If you want to talk about an outlaw, there’s the man. He doesn’t take what anybody says—he goes and finds out for himself. As best I can figure, Will Campbell is exactly what the Bible tells us to be.”

Jennings and his wife, the singer and songwriter Jessi Colter, met Campbell at the wedding of a mutual friend. It was the usual eccentric Campbell ceremony, held on this occasion in his office in Mount Juliet In one corner was a wood-burning stove. There were a few books scattered on a shelf and an old Olympia typewriter on a butcher block that was supported by a large antique milk jug. “I was immediately taken by this place,” Colter recalls. “It was very humble, very authentic. There was a pot of beans on the kettle. Then this man appeared who looked like something out of the eighteenth century.”

The wedding began abruptly with Campbell’s having the couple sign the marriage license. “Now what we have just done has nothing to do with Christian marriage,” said Campbell. “It is no more than a legal contract between you and the state that gives you the right to sue one another if you should ever desire to do so.” Campbell then tossed the contract aside. “Now, Mr. Caesar,” he said in a contemptuous voice, “we have rendered unto you the things that are yours.” At this point, the wedding begins.

Campbell spoke quite personally about the two people, the problems they had had in the past, ones they would no doubt have to face in the future and the endless need for forgiveness such a relationship demands. At moments he was so intimate that Colter could feel herself flushing. “The words he said went deep inside me,” she recalls. “The whole experience bonded everybody together. And I was very much drawn to Will. I felt no pressure, no condemnation in his presence. He’s far more of a force than what you’d call a force of personality or charisma. Of course, I couldn’t have said any of this at the time. I was working in a far place, spiritually.”

Campbell became an object of fascination to Colter: “Each thing I learned about him seemed just another wonderful trait. Here in this world, going at the speed of light, was this man who worked his own land, raised his own food, ground his own meal. He would come by to see us on his way to visit someone on death row or perhaps he’d just come back from some community where they were handling snakes. The next thing I’d hear he’d be lecturing at Vanderbilt. He was a prince of the unexpected.”

Campbell would be teasing around Colter, but he always wore his best manners in her presence. He treated her with extravagant gentility, so that when others would talk about Campbell’s drinking or chewing or cussing, it would seem they were discussing someone she didn’t know. He kept those parts of himself hidden from her. She knew him for years before she learned, second-hand, that he was a singer and a picker himself and that the song he performed more often than any other was one of her own haunting compositions, which became, in Campbell’s hands, a kind of benediction: “Storms never last, do they baby?/Bad times all pass with the wind/Your hand in mine steals the thunder/Your love makes the sun want to shine.”

When Tom Connelly’s biography Will Campbell and the Soul of the South appeared, Colter read it eagerly, although she was a bit shocked by the profanity Connelly attributed to Campbell. You don’t talk like that!” she complained to Campbell. “No, sugar, I don’t,” Campbell responded. ‘The man’s a goddamned liar.”

In the early Eighties, Campbell’s finances, always precarious, suffered from a drought of speaking fees and book advances, and he asked Waylon Jennings for a job. Jennings put him to work as a roadie. “After two days on the tour bus, unable to figure out exactly what job he had given me, I discovered that I was the one who turned the microwave oven on and off—I was the cook,” says Campbell. The crew took to calling him Hop Sing.

By then Colter had become a devout charismatic Christian. She and Campbell were having a kind of affair of the spirit. Jennings, on the other hand, had become remote and inscrutable, trapped in a narcotic inner circus that no one else could enter. Colter was frantic about the state of her husband’s soul. She asked Campbell to speak to him.

The story Campbell tells about what followed frankly puzzles me. I’m uncertain whether the point he makes is as significant as he seems to think it is—or if he inadvertently reveals a part of himself that is a bit star struck and vacuous. “About two o’clock in the morning on the way from Columbia, South Carolina, to Tampa, I decided to try it,” Campbell says in one of his sermons. “‘Waylon, what do you believe?’ I asked, almost tentatively. ‘Yeah,’ he said. Way down in his throat. Like he sings.

“Now, when you’re riding a stagecoach from Columbia to Tampa at two in the morning, conversations need not be rushed. There was a long pause. ‘Yeah?’ I finally muttered. Just what the hell is that supposed to mean?”

“Apparently he saw no need to hurry the matter along either. As the bus rolled on down America’s highway, into the night, we sat in contemplative silence. Then he said, Uh-huh.’

Looking back, I suppose that was one of the most profound affirmations of faith I ever heard.”

In 1976, Jimmy Carter received the Democratic nomination for president, which occasioned a conversation between Jules Feiffer, the playwright and Village Voice cartoonist, and Mike Peters, who draws for the editorial page of the Dayton Daily News. The two decided that before they could decipher Carter, they first would have to understand the South, which was terra incognita for both of them. They arranged for Doug Marlette, who was at that time working for the Charlotte, North Carolina, Observer, to set up a tour.

“We were told our first stop would be at the farm of some saint called Will Campbell,” Feiffer says. “Doug described him as a white hero of the civil rights revolution. So we drove out to Mount Juliet but instead of a saint, we met this rather grumpy, quite unfriendly truly unpleasant man.”

To Marlette’s alarm, Campbell couldn’t seem to get Feiffer’s name right. He kept calling him Fizer. Damn it, Will, it’s Feiffer,” Marlette would say and cite Feiffer’s books and plays, which should have been familiar even to a backwoods bumpkin like Campbell. Campbell merely shrugged.

They were all sitting on the porch eating boiled peanuts when Feiffer asked Campbell if he was “born again” like Jimmy Carter. Campbell acknowledged that he was. “By the way, Mr. Fizer,” Campbell continued, apropos of nothing, “how’s Kate?”

Before Feiffer could ask how Campbell knew the name of his eldest daughter, Campbell was called away to the phone. When he returned, he offhandedly inquired how Susan was doing. “How the hell do you know the name of my girlfriend?” Feiffer asked in astonishment “Here you can’t even get my name right, but you seem to have a complete dossier on my life.”

“That’s one of the features of being born again,” Campbell told him. “You know all about folks.”

It was late in the evening, after many songs and more than a little whiskey, before a thoroughly spooked Jules Feiffer realized that Campbell had followed his life and work avidly since his first book. “I had to pass the Campbell test of fire,” Feiffer says now. “He’s just not going to have people come down from New York and expect to cash in on their reputations. You have to prove yourself first.”

By then Campbell had seized control of their itinerary. “It was the Will Campbell Memorial Tour,” says Feiffer, “during which we learned nothing about the South and everything about Will.” They drove down to Oxford to see the site of the fecal—punch episode, then wandered into the Delta, visiting civil rights leaders and good old boys and wealthy plantation owners and famous writers—Campbell seemed to know everybody, from Compsons to Snopeses, and those he hadn’t met he quickly folded into his vast network.

Naturally, the cartoonists were struck by the “Will Campbell” persona, a caricature that came and went depending on the whim of its master. “I found it unpleasant,” says Manlette, who is a Southerner himself and who had once been something of a Campbell acolyte. It’s a great self-parody—this preacher who doesn’t like to be bothered, who doesn’t care for people, who dresses in this cartoon outfit. At the same time there’s this bizarre anti-intellectualism that is so Southern and so unattractive.”

Feiffer, on the other hand, was in love. “Here I am—a Judeo-atheist—buddying up to a Baptist anarchist,” he says delightedly. “When you’re alone with Will and he’s just being Will, you get into the most complicated, thrilling conversations. There’s a cool distance but also a great deal of sweetness there.” At the same time, Feiffer saw Will Campbell as being more like a character in a novel than a creature of real life. “He will oppose the image of a bourbon-swilling, expectorating-in-a-Coke-bottle character with the cane and the hat—but you don’t come by that stuff by accident,” says Feiffer. “I think he prefers the mythologizing because it keeps you from getting at the truth. The truth for him is too personal, and he’s too vulnerable. It’s almost as if he has to put on a persona in order to be real.”

Perhaps the mask has grown onto the face, so it’s no longer possible to see who the real Will Campbell is. He hides that part of himself even from those who are closest to him. “Sometimes it’s hard for me to separate him from the legend,” says Penny Campbell, a thirty-seven-year-old lesbian and political activist in Nashville who is the eldest of Campbell’s three children. “I wish he could let that persona down with his family, but a lot of times he doesn’t do that. He’s just not able to carry on an intimate conversation with his children. It’s painful sometimes.”

It’s painful for Campbell, too. The gulf he creates between himself and others is almost too great for him to bear. “When I went to first grade, my father stood outside the window the entire morning,” Penny says, “and when he took me to college my mother said he cried the whole way home. But I never knew about this. I always saw him as someone who could stop a conversation with a single cutting sentence.”

Campbell has spent his life spiritually mothering others, and yet there is some immense unconsoled sadness inside him. It is as if healing the world were a way of healing himself. I had learned enough about him now to sense some of his sadness. His mother was an unapproachable, unhappy woman afflicted with imaginary illnesses, who sometimes ran off into the woods to hide from her family. His older brother and childhood hero, Joe, died of a heart attack brought on by years of drug abuse. He endured the loathing of people he grew up with and loved—because of who he was and what he believed.

I could see that behind the priest and the prophet and the religious down—behind “Will Campbell”—was a hurting child, a small, sickly, almost unnoticed boy who had been made special only because he had been given to God. And what would be the greatest tragedy imaginable for such a person, what would cause him to erect this extraordinary public façade? “I think when you get to the bottom of Will Campbell,” says his friend Tom T. Hall, “what you’re going to find is a Jesus-loving agnostic.”

“I’m not very old, but I have seen a lot of changes,” said Will’s ninety-one-year-old father, Lee Campbell.

“Me too, Daddy.” Campbell was sitting on the screen porch of the white farmhouse he grew up in, staring at the passing pulpwood trucks on Highway 24. It would be one of Campbell’s final visits with his father, who died shortly thereafter.

In a little while we got up to go visit some of Campbell’s kinfolk and see the sites. This was sacred ground. There were ghosts all around. Here on the road to Aunt Dolly’s house was a place where trees don’t grow. There once was a schoolhouse there. That was where they found the body of Noon Wells—a black man who was murdered by two jealous husbands—in the schoolhouse door. Here was where the store used to be where Lee Campbell’s oldest brother, Uncle Jessie, was shot in the leg by a crazed storekeeper. The gangrene later killed him. Over there was where Mama and Aunt Dolly saw Lum Cleveland and his wife, Aunt Stump, get killed by their son-in-law, Allen Westbrook. “I saw Allen Westbrook hanged at the Liberty Courthouse,” Mr. Lee said. “I never want to see something like that again.”

Gradually nature is reclaiming the landmarks. We drove past abandoned homesteads with the martin gourds still hanging above the untended gardens. This part of Mississippi was once ruled by the Choctaws and the Chickasaws; now only the old folks stay, and many of the people Campbell grew up with are gone. There are still some Choctaws around, however, and lately Campbell has been studying their language.

This place has marked him. He carries Mississippi around with him, like the long pallid scar of the rat bite on his index finger. I realized as we drove through the second-growth pine trees that Campbell wanted me to understand this about him.

We crossed the East Fork of the Amite River—a negligible little stream that can be jumped over at nearly any spot. There was one sluggish, muddy swell under the beech trees where a couple of black men in overalls had stopped to fish. “The Glory Hole,” said Campbell. “I was baptized right here on a Sunday morning in June of 1931.” Across the creek was the East Fork Baptist Church, once a simple frame building constructed of longleaf yellow pine in 1887, which has since been rather handsomely bricked over. One of Campbell’s earliest memories is of the Ku Klux Klan marching into the middle of a service and presenting the pulpit with a new Bible. Later, when he preached his first sermon in that pulpit at the age of sixteen, he could feel the raised letters of the KKK embossed on the back of the cover.

Mr. Lee began to recount that first sermon and how Will had written it out and nailed to a plow, then spent weeks delivering it to the rear end of a horse as he filled the fields. The title of the sermon was “In the Beginning,” and it compared the opening chapters of the Bible to the new life that was facing the graduating seniors of the East Fork school. “After that,” Will said, “I was a full-fledged preacher, entitled to buy a Coca-Cola at a clergy discount.”

We drove up to the cemetery, which sits on the highest spot in the neighborhood. The plastic flowers on the headstones are shaded by giant oak. Campbell’s first job was tending this plot; he received fifteen dollars a month from the East Fork Cemetery Association for cutting the grass and weeding. At the end of the summer, when he had amassed the sum of forty-five dollars, he left Mississippi, and in many respects he has been trying to get home ever since.

Campbell’s people are buried here. I thought of a song Campbell wrote at three o’clock in the morning in the early Sixties, when he was riding back to Nashville from Mississippi, in exile from the people he loved and the place he came from, longing for the reconciliation he so often preaches. He called the song “Mississippi Magic.” It is a tale of his own death, when he will be loved and accepted again by the people who raised him. They will come from miles around to the old Hartman Funeral Home, in McComb City, to stand around his coffin and say, “Ole Will was a good old boy, he just had some crazy ideas ….”

“Then that Mississippi madness, be Mississippi magic again/’Fore we was born we were all kin/When we dead we’ll be kinfolks again.”

“Is this where you’re going to be buried?” I asked him.

“Yep.”

“Where exactly?”

“Well, I’m not going to show you that. You’re just gonna have to find it yourself someday.”

I realized I had gone as far as I could go with my guru. I had set out to see who he really was and whether I could accept his teachings. I had tried as much as possible to pry off his mask of authority and see the person inside—the flawed, insecure, fallible, often foolish person who was no better than I. And I had seen that person or at least caught a glimpse of him. He seemed to me like a deer I had once come upon in the woods, who had given me a brief, direct look, passing some piece of obscure intelligence between us, and then had fled into the cover. But I had seen him, nonetheless.

And somewhere in the process of seeing him, I had come to love him.

I couldn’t say that to him then. Instead I asked a question I knew for certain he couldn’t answer. I asked him what was the meaning of life.

He laughed. “How the hell do I know? Go ask God—he started it.”

[Photo Credit: Walker Evans via The Art Institute of Chicago]