All right, let’s start with the head.

Say check-out time is 1:00 and everybody who reads this magazine is stuck in a room at a Holiday Inn somewhere in Louisiana because nobody can figure out how to unlock the security chain, and there’s a water moccasin in the bathroom—the water down there doesn’t taste too good anyway—and there’s nothing in the room furniture-wise that’s substantial enough to break down the door.

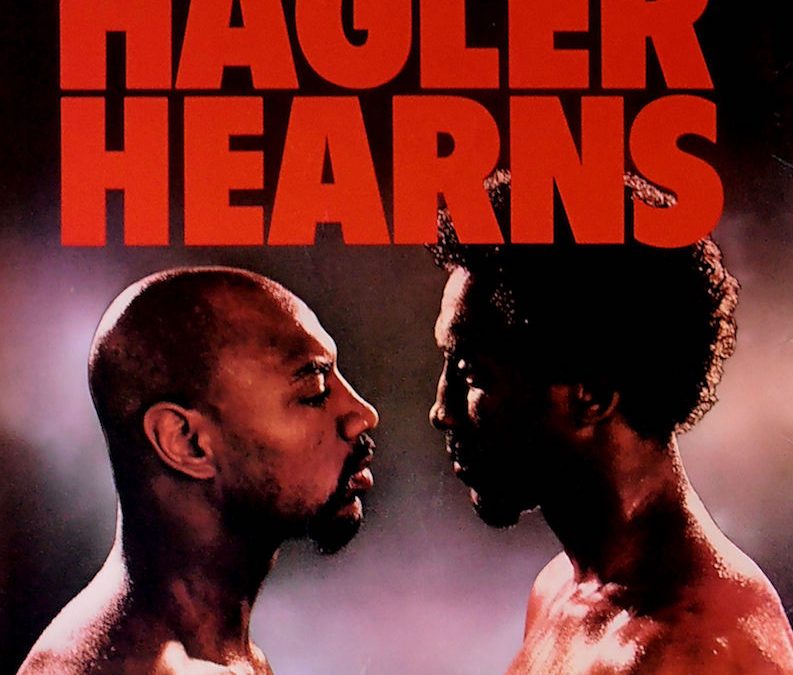

And as you’re filling out one of those would-you-take-a-moment-and-help-us-improve-our-service cards, you happen to look over at the bed and there is Marvin Hagler’s head lying on a pillow, shining like the Hope Diamond. It is, of course, the perfect thing to splinter a Holiday Inn.

The question is, though, how are you going to ask Marvin if it’s all right to use his head to break down the door? Even if you didn’t happen to know who Marvin was, you’d know you have to ask.

There is just something about him that tells you not to touch anything without permission.

Marvin Hagler is the undisputed middleweight champion of the world. That means that all the fat boys who run the organizing bodies of boxing—which is as sorry and contradictory a collection of human beings as the planet has to offer—have all somehow agreed on Marvin as the best 160-pound fighter in the world.

Hagler is still on fire. It takes a little longer to see it than it used to, but it’s still there.

He has been the official champion for more than four years—since he broke Alan Minter to pieces in London in 1980—but for at least three years before that he was the best fighter in the division, one of the two or three best in boxing.

And, understandably enough, for a long time nobody wanted to fight him. It is a tenet of boxing, and I suppose of life itself, that it is more fun to be champion of the world than to have Marvin Hagler change your liver and kidney functions on Home Box Office. Marvin didn’t see it that way, though, and he was on fire about it the whole time.

Soaked in sweat, he would stand in front of the television cameras after every fight, barely acknowledging congratulations, and ask what he had to do to get a title shot. Sometimes you’d see half a dozen guys behind him, wearing towels around their necks and Q-tips in their teeth, getting the opponent back to his feet.

Hagler would be looking into the camera, saying, “What have I got to do, kill somebody?”

At least once it looked like it might have happened. A fighter named Loucif Hamani lay unconscious through the post-fight interview and for several minutes after that. Hagler says, “I remember I was walking around the ring with my hands up, and Bob Arum [who promotes Hagler’s fights] ran around the apron after me, pointin’ at Hamani, and he’s screaming, ‘Look, you goddamn fool, he’s still hurt.’”

In 1979, Hagler got his first title shot. It was against Vito Antuofermo, the scariest-looking man alive. To quote another fighter—the heavyweight Randall Cobb—“Vito looks like everything you’ve ever been afraid of about New York City.”

That night Hagler clearly won, but the fight—unexplainably, as with most everything in boxing—was scored a draw. And Hagler was on fire about that, too. He said, “What do I have to do, kill him?”

And when the cameras went back to Antuofermo, you couldn’t help wondering if what you saw could be killed.

But that was five years ago.

Ten months later Hagler took the title from Minter, and he has defended it ten times since. He has made millions of dollars; he has been called the best fighter, pound for pound, in the world. He’s had his name legally changed to Marvelous Marvin Hagler, and as I write, he is beginning training for a fight that will earn him at least $5.3 million against Tommy “Hit Man” Hearns of Detroit.

The more money you make, the more people you got want to be your friends. You walk away and hear them mumblin’ behind you.

All that, and he gets the “good” plane for the promotional tour, the one with the Pac-Man machine. As champion, he feels he is entitled.

And even so, there is something missing.

Because Hagler is still on fire. It takes a little longer to see it than it used to, but it’s still there.

I find Marvin in a ring on the third floor of a gym in Brockton, Massachusetts, leaning against the ropes in monogrammed blue velvet trunks, while a man from a European country where they speak English without vowels walks back and forth behind him, carrying a smoke machine. There is a red light over Marvin’s head and a photographer from a high-gloss magazine kneeling on the other side of the ropes, taking roll after roll of pictures.

She poses him “thoughtful” and “mean” and “determined” and “triumphant.” She has him flex his arm muscles, both at once and then one at a time. Every two or three minutes she stops, and one man reloads her camera, and the other one walks behind Marvin, making new clouds of smoke.

“That’s great,” she says. “Oh, that’s great. Great, great. It keeps getting better the time. That’s it, but this time, Marvin, could you kind of raise both gloves up over your head? Great, that’s great….”

Marvin coughs and disappears in smoke. “Could you put your foot up on the rope?” she says. I see what she is after here—it’s that picture of Ernest Hemingway standing on some zebra he just shot—and Marvin tries, but the ropes give and even the photographer sees this is not great. The accompanying silence is enough to break your heart, but Marvin saves everybody’s feelings. He puts his hands on his hips and looks hard at the camera. “This right here’s my ‘superior’ look,” he says.

“Oh, that’s really great,” she says.

It goes on for an hour. The poses repeat themselves, over and over, but Marvin is patient. “Do you put anything on your body to make yourself sweat?” she asks, looking through the camera.

“Exercise,” he says.

And that’s great, too. And the thought occurs to me, somewhere in the middle of this, that Marvin will stand here in a cold gym, in a cloud of artificial smoke, striking unnatural poses in velvet shorts for as long as this woman will take pictures and say “great.”

And it suddenly occurs to me that a man who takes the time and trouble to have his name legally changed to Marvelous might not have been smiling when he did it.

When the photographer has finished, I follow Marvin back to the locker room. He dresses carefully, without a mirror, feeling his tie and collar to make sure they are straight. I ask him about fighting Hearns.

“I look at all these guys,” he says, “Cooney, Holmes, Hearns. I been out there longer than any of them, but it took me so long to earn any money. Not like them. Hearns, he’s a freak. Tall and skinny like that, they call him the hit man. That’s where the money come from for him.

“It took me a long time to even get on TV. I was the first black fighter from Brockton ever got out of this state—none of them had to do what I did. When I look at it now, it just make me work all the more harder, knowin’ what I did to get here.”

“What about the fight?” I ask.

Hagler, to my mind, is the more complete fighter, but there is something almost mechanical about him that a fighter as quick as Hearns can take advantage of. On style, I think Hagler is in for a long night.

Marvin Hagler can’t get the years back and make them right.

He shakes his head. “He can’t fight backing up,” he says. “I fought people hit harder than him, and I fought better boxers. He can’t do nothing. He’s a freak, to be that tall and skinny, make all that money. All the things I had to do to get what he’s got…”

I ask whether he saw Hearns knock out Roberto Durán last June. Hearns crushed Durán that night, in two rounds. In late 1983 it had taken Hagler fifteen rounds to beat him by decision. “Did some little voice in the back of your head say something to you when you saw that?”

“Like what?”

“Like, ‘Fuck me, let’s run away.’” Hagler shakes his head. “All the things I had to do to get here,” he says, “I forgot about what scared was.” And I believe that a little bit. Over the years he’s never sounded scared, he doesn’t seem to have considerations about what can happen in the ring. He talks about fights like somebody’s manager. Where’s the money?

“I forgot about fun, I forgot about scared,” he says. “It’s a serious business now.”

“Don’t you ever play in the ring?”

He shakes his head.

“What about sparring? You must like some of those guys if you’re working with them every day….”

“I kind of like the ones that hang in,” he says, “but there’s no friends in the ring. No friends, no blood [Hagler’s brother is the middleweight Robbie Sims]. It’s the same thing with [Sims] as anybody else. They’re just fresh meat.

“I bring them into P-Town on an airplane and ship them out on the Greyhound if they don’t earn what I pay them. I stay up [in Provincetown] to get mean. The harder the fight, the harder I work, the meaner I get. It’s business….”

And business is good.

And Marvin is still on fire. “The more money you make,” he says, “the more harder you have to work. I don’t know why. The more money you make, the more people you got want to be your friends. You walk away and hear them mumblin’ behind you.

“When I started, I used to fight to get my way out of here. But my mother loves this town. I like it, too. So what you want then don’t always turn out to be what you want now.”

And I ask Marvin what he wants now.

He tucks his tie into his pants and slips into his suit coat. “I want for all them years,” he says, “couldn’t get my shot, couldn’t make no money. I never forgot what that was like.”

But as far as he’s come and as big as he’s gotten, Marvin Hagler can’t get the years back and make them right.

And as far as he’s come, he can’t let them go.