Every show reflects the character and quality of its star. When you enter the Perry Como studio, the atmosphere is warm and friendly, and total strangers will come up and tell you about their kids. The Sid Caesars were kicky and lunatic, but always a little nervous and unsure. On the old Phil Silvers show it was like a varsity locker room during halftime, with the Bilkos out in front.

When you walk backstage in CBS’s Studio 50, where the Jackie Gleason show lives, you’re carried back to the raucous days of vaudeville, the era of “Sixty-Cent” Albee and “Grifter” Keith. You might be in the wings of the Alhambra, the Palace or any one of the cockamamie Bijous on the United Booking circuit. You’re surrounded by giants, dwarfs and fat ladies, bears on bicycles, cops and firemen in uniform, Third Bananas in fright-wigs and pert little hoofers in Albertina Rasch costumes, all as pretty and talented as Al Jolson’s first wife.

On the right side of the house, the show band is rehearsing ricky-tik at a galloping up-tempo. House left, the sound man in the balcony is testing all the modern improvements on the slap-stick: explosions, fire alarms, sirens, Canaveral shoots, glass crashes and shotguns. In the orchestra seats, visitors sprawl and cut up old touches about the Twenties.

In the center of the former orchestra pit stands the great clown, Herbert John Gleason, wearing an orchid-colored sweater, eating cold shrimp off a paper plate, staring balefully at a TV monitor, whistling through his teeth and hollering, “Hold it! Hold it! Sammy, is he using sticks on that bongo? I want mallets. Real vaudeville style, like the Halsey.” He stares up into the balcony. “No, no, no! Make that firebell faster. This way it sounds like we’re going to announce an out-of-town fighter.”

He glares at a tenement set and criticizes the placement of the garbage cans. Someone in the orchestra says, “Those curtains in the window, that’s the kind of lace curtain my grandmother had.” Over his shoulder Gleason calls, “That’s the kind of lace curtains my grandmother wore.” His visitors are dutifully convulsed.

Gleason leaps onstage. “Hold it! Hold it!” He demonstrates the burlesque take he wants one of his Bananas to use. Instantly his face is running with sweat. The actor cannot capture the ancient bit to Gleason’s satisfaction. “Should I do that blackout myself?” he asks his producer. Instantly there comes a chorus from the producer, the producer’s wife and the dance director, “Please, Jack. Please! It’s flat without you. It’s nothing. Please.” “All right, I’ll do it,” Gleason mutters. “Somebody better tell him.”

He grabs a microphone and hollers, “Hold it! Hold it, Frank! Don’t pan on that shot, it takes too much time.” From the controls the director answers, “Why don’t you wait and see what we’re trying to do, Jack?” “I know what you’re trying to do. You’ve got to start with a full shot, cut to an insert, cut back to full and then zoom in. Got it?” In sarcastic surprise the director says, “Very good, Jack. Thank you.” “You’re welcome,” Gleason says. He takes a beat and then calls over his shoulder, “Maybe we’ll pick up his option for next week.” Again his visitors are convulsed.

He goes up to the lounge in his dressing room, as naked and arid as the dressing room of a prelim fighter in the old St. Nicholas Arena. There, half a dozen of his enormous stable of writers present some pages of jokes. They stand frozen, except for a jerky drag on a cigarette, while Gleason reads and rereads the pages. Finally he looks up and delivers his verdict. “I told you. No more fat jokes. No more Sammy Spear jokes. I can’t use any of this.” The writers shuffle out drearily. Gleason stares, coldly and implacably, into the blank television screen built into the wall.

This is the atmosphere of the American Scene Magazine, a rough, tough, one-man circus, heir to every vaudeville show, every carnival, every burlesque, every nightclub act that ever played the back streets from Schenectady to Sheboygan. It is an encyclopedia, a history, a mausoleum of the situations and sight-gags developed through centuries of clowning. It could have played Hammerstein’s Victoria 50 years ago. It could have played the Theater of Marcellus 2,000 years ago.

Gleason alone winds the key that sets his golem in action on Saturday nights. He writes, composes, directs, produces, performs and has no compunction about revealing that he neither trusts nor respects his staff. He alone is responsible for the pace and taste of the show, from the June Taylor Dancers who open it with their resurrection of the Goldwyn Follies to Frank Fontaine’s spastic saloon spot that usually closes it. For Gleason, this is meat-and-potatoes entertainment, and 20 million viewers agree with him, at least according to the ratings. But for viewers of any taste or sense, his show is the quintessence of vulgarity.

A man’s taste is a man’s history; but before going into Gleason’s background it must be clearly understood that the American Scene Magazine is the real Gleason. He is not pandering to the public, writing down, cynically exploiting his admirers. He is doing the best that he can, the best that he knows, unaware of the fact that his entertainments are on a level with the cartoon inventions of Rube Goldberg’s Professor Lucifer Butts. The question is: how were his horizons—bound by slums, drunks and schoolboy slapstick—formed; and why does this empty clowning appeal to the American public?

In the first place, he was brought up in an environment of slums, drunks and slapstick. This is no secret. His history has been so much publicized that it’s turned into a romantic legend: poor Irish boy born in Bushwick, father deserted family, mother died, leaving him orphaned at 14, and so forth. One has only to mention the magic word “orphan,” and instant sympathy is generated, which is rather strange in an age when people are spending fortunes on psychoanalysis to get over the hatreds and resentments of—or toward—their parents.

What is even stranger is the fact that Gleason will not outgrow his slum standards. Other artists do: Lee Strasberg, for example, a poor Jewish boy from the lower East Side who is proud of his origins. “Lower East Side boys feel like they were pioneers,” his wife Paula says. Strasberg has moved up to a towering and tasteful position in the creative theater. Gleason, with equal opportunities, prefers to remain the Bushwick clown.

He was a clown in P.S. 73 in Brooklyn, a skinny, gangling kid, much admired for his slapstick and pool-sharking by his friends whose names he still uses on the show: Paddy DeNoto, Fatso Fogarty, Teddy Gilanza, Bookshelf Robinson, Julia Dennehy (his first girl) and Crazy Guggenham. He clowned at his grammar school graduation, went to high school, quit after two weeks and says he began hustling jobs as a comic. The legend conveniently ignores truant officers.

“When I first started, I’d play anywhere,” Gleason said. “It’s not true, George Burns saying there ain’t no place for kids to be lousy any more. There are plenty of places. I’d play bazaars, church suppers, block parties, reunions, Elks conventions, amateur nights; anything to get on, and I went on for nothing.”

Danny Thomas once said to him, “I got my first laugh in a theater in Toledo.” Gleason said, “I got my first laugh in front of a theater in Brooklyn.” He used to entertain the queues at the box office of the old Folly Theater, renamed the Halsey, still his yardstick of professional competence. He competed in amateur nights at the Halsey, supported by his loyal claque, and eventually became the amateur night M.C. for four dollars a week.

In the mid-1930s, aged 17, he made it as a professional, going to the Miami Club in Newark at $14 a week. He had a rowdy, brawly, pool-parlor act with a wise-guy insult pattern. He has a bitter memory of ice, plates and food being thrown at him. He claims to have been in an altercation with a customer who was throwing pennies at him. He asked the guy to step outside and was flattened by the customer, who turned out to be “Two-Ton” Tony Galento.

Gleason racketed around in a few more Jersey traps, married a dancer named Genevieve Halford when he was 20 and had two daughters, Geraldine and Linda. It’s common knowledge that the marriage broke up, allegedly because Mrs. Gleason loathed show business. It’s also common knowledge that the Roman Catholic Church makes divorce and remarriage impossible.

“I’m always suspicious of passive people,” he told me. “All life is based on antagonism.”

During the early years of his marriage, Gleason went to the Club 18 on 52nd Street as Third Banana to Jack White and Pat Harrington at $75 a week. He was still rowdy and insulting. He would hand Sonja Henie an ice cube and say, “All right, honey, do something.” Or intercepting a woman coming out of the ladies room during the show, he’d call, “Could you hear us in there, honey?” “No.” “Well, we could hear you.”

This was in the 1940s, when Hollywood moguls tipped the help with stock contracts. One of them landed in Gleason’s ample lap, and he went to the Coast, where he made half a dozen B pictures and worked nights insulting the clientele in Slapsie Maxie Rosenbloom’s restaurant. He got nowhere in Hollywood, and alter two years drifted back to New York, where a novelty called television was giving a new lease on life to obsolete variety acts. Frank Bunetta, Gleason’s present director, was working for the old Du Mont station, which was Channel 5 in those days, and describes Gleason’s advent in 1949.

“Dr. Du Mont was only interested in experimental television; it never occurred to him to sign a performer to a contract. So when we started Cavalcade of Stars with Jack Carter, and he became a star, NBC snapped him up. Du Mont replaced him with Jerry Lester and Dagmar, and NBC grabbed them. Then Du Mont found Jackie. He was around. He’d been on The Life of Riley, and then for some reason he wasn’t there anymore, so he came over to us.”

Asked what Gleason was like to work with in those days, Bunetta said. “He had discipline. Later, he began to believe his press and lost it. Now I think he’s getting it back again.

“He needs challenges. He needs competent professional actors to bring out the best in him. Jackie is the most innate kind of guy today. He isn’t studied, like Sid Caesar. He doesn’t fall back on any bag of tricks. If a situation arises that never happened before, he’ll overcome it and make it funny. Jackie is an innate funnyman.”

“He’s certainly an innate fussy man, the way he picks at details.”

Bunetta smiled. “Jackie’s the kind of guy that would find something wrong with the Mona Lisa. Once I said to him, ‘Jack, you rule with an iron head instead of an iron arm.’ ”

Those early years at Du Mont developed Reggie Van Gleason, loud-mouthed Charlie Bratton, Joe the bartender and, above all, that tender tenement idyl, “The Honeymooners,” with Art Carney and Audrey Meadows. This time it was CBS who grabbed him from Du Mont in 1952 and signed him to a long-term contract. From there on, the success snow-balled. We all know about his TV series and specials; his Broadway triumph, “Take Me Along”; his films, “Soldiers in the Rain,” “Papa’s Delicate Condition,” “Requiem for a Heavyweight,” “Gigot” and “The Hustler.” His present contract with CBS runs until 1972 and guarantees him a minimum of $100,000 a year, work or not. His present show is budgeted at $150,000 a week.

The Gleason empire occupies two floors in the tower of the same Park Sheraton Hotel where Albert Anastasia and Arnold Rothstein had less fortunate dealings. The office floor has a great central hall furnished with a few lounges and decorated with photographs, costume designs and rave reviews of Gleason. Two bright young ladies guard the entrance and answer incoming calls, preferring to holler, “Pete! Pick up five!” rather than use the phone signals. From the floor below comes the heavy clatter of the June Taylor Dancers in rehearsal.

Swinging saloon doors (one broken) hang before the anteroom to Gleason’s office. Over the office door itself is a sign in simulated bronze: OUR BELOVED FOUNDER. The office is large and tailored and decorated almost exclusively in blue: blue carpet, matching chairs and settee in blue stripes, a purple lounge chair, blue curtains. On the walls are clown pictures and two golden records, awards for Gleason’s best-selling albums, Music for Lovers Only and Music, Martinis, & Memories.

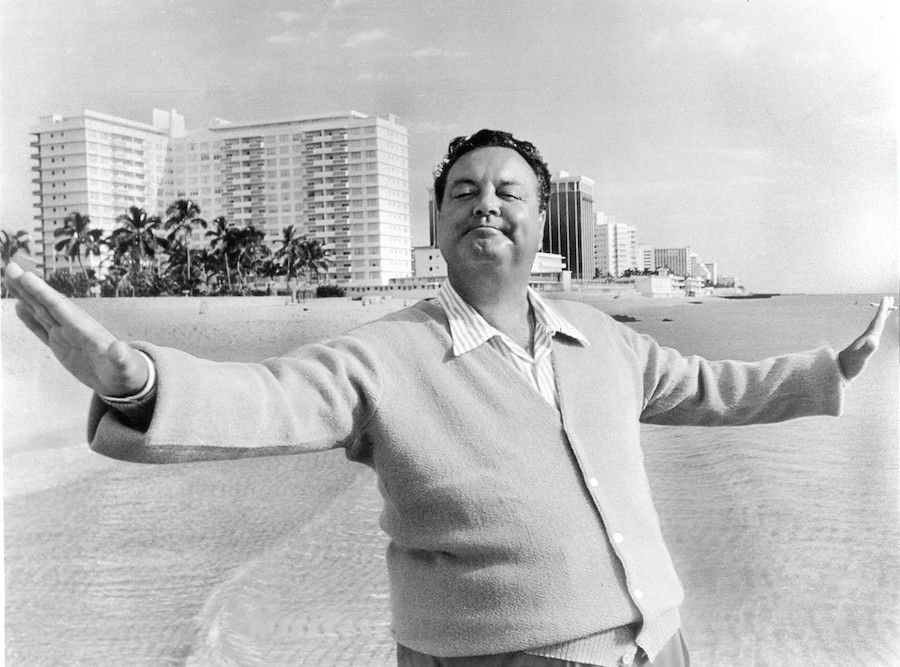

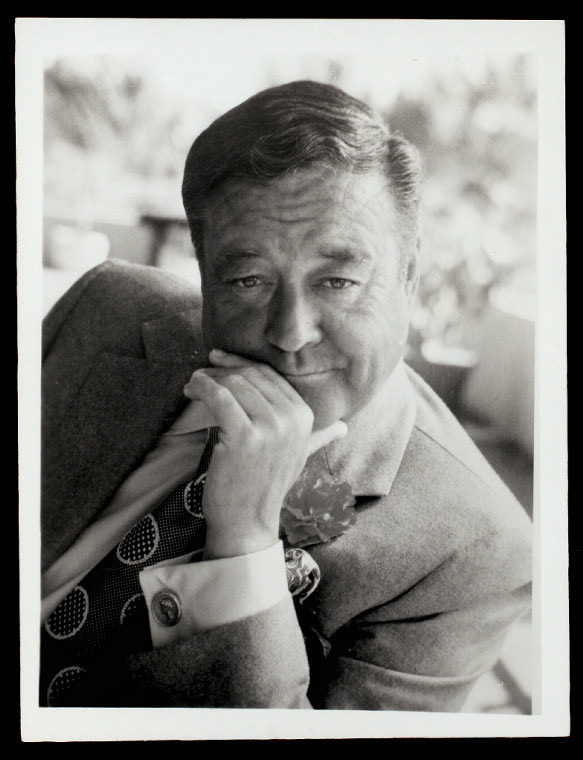

Wearing a white-ribbed coat sweater, Gleason sat at his desk over a ten-o’clock snack of matzos, Swiss cheese and black coffee. His face is ten years younger off-camera, and he could be handsome; but his 260 pounds make him reminiscent of Herman Goring, or the Fat Boy in Pickwick Papers.

He gave me a polite smile that was massively reserved, told me to call him Jackie and then, out of the blue, referred to something we had discussed briefly in a chance meeting at Toots Shor’s ten years before. I had not met him since.

This was not show-offery: it was merely a demonstration of the phenomenal memory that has brought grief to so many actors who have worked with him. His producer, Jack Philbin, swears that they could hand him a 60-page Honeymooners script at seven in the morning, and four hours later Gleason would have it down cold. With a memory like that, Gleason never finds it necessary to do much rehearsing, to the despair of his casts. “What’s my cue, Jackie?”, Art Carney would ask in desperation. “Never mind the cue,” Gleason would answer. “Just watch me. Watch me.” A more embittered actress reports that his sole directions to her were, “Don’t get between me and the camera.”

Asked about this, he admitted it was true, but insisted that it was no problem as soon as he managed to surround himself with actors capable of improvising and thinking on their feet. “Art Carney, for instance. In one of the Honeymooner sketches the door stuck on his exit. Art just went out the window and up the fire escape like it was the most natural thing to do. Anyway, too much rehearsal destroys spontaneity.”

“They tell me you do most of your rehearsing in your dressing room.”

He nodded.

“I’d like to sit in and watch you work.”

He shook his head. “No, that’d be bad for the actors. You’d make them self-conscious. It’s a question of time. There’s just so much time to get things done, and I can’t afford to waste it on actors worrying about you.” Suddenly he bawled, “Sydell! Bring me some cigarettes.”

His secretary, a white-blonde, zaftig girl with a cheerful face, entered with cigarettes and left. Gleason lit up and waited for the next question, staring impassively at his desk. Usually in interviewing, the first meeting is spent in an attempt to establish some kind of simpatico relationship with the interviewee. Conversation is exploratory. You search for subjects that are of mutual interest and concern, so that links can be found between you. Later, these links are forged into an understanding, and then the interviewing really begins.

It was impossible to establish a link with Gleason. He was animated about nothing. We discussed the Art of the Straight Man, amateur astronomy (he owns a small telescope), the difficulty of assaying audiences, the Irishness of his shows (he flatly denies this, on the grounds that he uses very few Irish names), stickball on New York streets, deliberate break-ups on stage (Gleason condemns them as cheap), the possible relationship between pool and golf (Gleason is expert at both) and the homosexual influence on choreography.

It was impossible to get his conversation to flow easily and naturally. He remained measured and reserved, and each sentence he spoke sounded as though it had been said a thousand times before and would be said a thousand times again. Each thought he expressed sounded as though it had been formulated years before and would never be changed; perhaps because whoever or whatever had created this Billiken no longer existed. In desperation, I attempted to stir him up with a critical discussion of the characters he used on his show and mentioned that my only favorite was the Poor Soul, who had a touching quality.

“Vanity is an actor’s courage. It isn’t built by success. If he waits for success to bring vanity, he’s cooked. He must start with vanity.”

“Yes,” he said carefully, “but The Honeymooners was based on pathos, too. Ralph Kramden is a loud-mouthed bus driver, bluffing because he knows he’ll never amount to anything. All the characters have reason to be sad. And there are morals in the characters. Reggie Van Gleason’s never drunk, you only see him drink; but the frightful results would please the W.C.T.U. On the other hand, you never see Rum-Dum drink, but he’s always drunk; he’s in complete euphoria. He can’t cope with anything. That’s why he has a big moustache.”

“Why?”

“Because he’s so drunk he has no time to trim it. He just lets it grow. Now Reggie combs his hair flat because he’s a drunk. All drunks comb their hair back flat,” Gleason said profoundly. “Mostly because he combs it in the morning when he has the horrors. The Poor Soul combs his hair back because he has no ego. On the other hand, Arthur, in the Arthur and Agnes sketch, does all he can with his hair and wears his hat on the back of his head.”

“Is this significant?”

“Yes. He’s like Charlie Bratton. He’s an opinionated man, and he wants his whole face to be seen when he’s speaking.”

“Jackie, I can’t ever believe in Reggie Van Gleason. The whole concept of the rich n’er-do-well is old-fashioned to me. People like that just don’t exist anymore, if they ever did.”

He shook his head solemnly. “You’re wrong. There’s something of Reggie in everybody. At one time or another, every man wants to kick his father.”

“And that silly Charlie Chaplin moustache ….”

“It isn’t Charlie Chaplin. It’s an upside-down Chaplin moustache.”

“Why does he wear it?”

“Because he’s vain. All people who wear moustaches are vain. You still meet Reggies today. I was in a bar once and I got in a fight with a guy. We went into Central Park and I took off my coat and started in, and he waved his hands at me and said, ‘Not so fast.’ ” Gleason smiled briefly. “Now wasn’t that Reggie?” Suddenly he bellowed, “Sydell, I want a half a dozen clams and filet of sole.”

From the office next door, his secretary hollered. “A dozen clams, Jackie?”

“Half a dozen.” He lit another cigarette and waited, eyes fixed on the desk.

“Do you disagree with Scott Fitzgerald, who believed that rich people were different?”

“Yes, I do,” he said judgmatically. “Because if rich people were different they’d get into different kinds of trouble, but they don’t. They get into the same kind of trouble as poor people; they just have more opportunity to get into trouble. The one difference between wealth and poverty might be that the rich cannot be given as much credit for generosity.

“No, Reggie is just like all people, except that poor people are afraid to steal because they may get caught. Not Reggie. You know the expression: What did you do for me today? Reggie’s motto is: What did I do for me today? He’s vain and self-centered. In other words, Reggie has the courage of his contempt.”

But asked whether he felt he put something of himself into the characters he created, Gleason absolutely rejected the idea. He did not convince me.

While continuing with Gleason, it was necessary to make a few inquiries about his famous multi-talents. How much of a composer is Gleason? He admits that he can’t read music, can’t write music and can’t play an instrument. He picks out his tunes on the piano with one finger, hums them into a tape recorder to make sure he’ll remember them and then brings them to an arranger. He knows exactly what he wants in tempo, harmony and color, and second-guesses until he’s satisfied with the results. It’s said that Charlie Chaplin also “composes” this way.

Sammy Spear, Gleason’s conductor, and an old pal from the Halsey theater where he played trumpet in the pit, swears that Gleason has a fantastic ear for music. “He’ll holler. ‘You got a shrimp.’ That’s what he calls a wrong note. Now some people can spot a wrong note: some people can spot the direction of a wrong note, and that’s good enough for a lot of conductors; but Jackie can spot the one violinist in three tiers of violins who played it.”

What sort of a conductor is Gleason? One of his musicians describes his technique, “He tells us what he wants and then goes into the controls to hear how it sounds. For instance, he’ll say, “You’re standing on the street corner. You’re a lonesome son of a bitch. You haven’t had a girl in so long. Then a girl comes down the street. The street lamp is behind her and shows her through her dress and you can see she’s for you, and you go Rrrrruh! That’s how you play.”

“The only reason people drink,” he went on, “is to change themselves, to become another person. If anybody says he drinks for any other reason, he’s kidding himself.”

What kind of a writer is Gleason? Will Glickman, a former member of the stable, says. “He can’t write at all in the script sense, but he’s very creative and inventive in outlining a scene. That’s why he loves to do pantomime. Words bother him. The actual words are mere details, something for secretaries. He thinks pantomime is fundamental comedy. That’s why he was so happy to play Gigot.

“He reduces everything to fundamentals. If you play a sketch in a living room, you can’t have a prop or a window or a door that isn’t used. He’ll say. ‘What’s that window doing there? Does anybody fall out of it?’ You tell him, ‘No. Jackie, it’s just a window. This is a living room, and living rooms have windows.’ He throws it out.”

How versatile is Gleason? Another former associate says, “Gleason believes he can do any job on the show better than anyone else—writing, directing, conducting, set design, even business management. He’s convinced he’s surrounded by incompetents. Now this is true of main stars, Jerry Lewis, Red Skeleton, Milton Berle … only they’re not as bad as Gleason.

“But the killer is, he can do a lot of these things. The son of a bitch is so talented, such a tremendous performer, that it overrides all the exasperation. He really knows his craft.”

Perhaps. I’m skeptical of these appraisals because of the people who make them. They’re most of them the Broadway crowd, sophisticated illiterates who confuse culture with “class” and are staggered by anyone who can display more than one aptitude. But aptitude is not talent.

It’s difficult to judge Gleason’s creativity, he’s so guarded and concealed. His music, impossible to remember, seems to be about on a par with Steve Allen’s anonymous tunes. He permits no one to attend his script conferences, so I can’t say whether he really writes or merely second-guesses the professionals. His 90-minute drama for CBS two years ago, The Million Dollar Incident, which he conceived, wrote, directed and performed, was so amateurish that it was an affront. The sets in the American Scene Magazine can’t be an example of his design: they’re all borrowed from Balaban & Katz’s two-a-day in Chicago.

As a businessman, his forte is spending money. This also impresses the Broadway crowd, which is awed by anything framed in dollar signs. It has also impressed itself on talent agents who now know that the one sure way to get Gleason interested in an act is to warn him that it’s extremely high-priced. He has never been known to haggle over money, and when I asked him what the weekly budget on his show was, he off-handedly said that he hadn’t the faintest idea.

I have frequently been asked. “How does Gleason get away with this talent myth?” The answer is simple but not obvious. It is not that he has patronage to distribute. It is not the inadequacy of the people with whom he is dealing. It is the fact that Gleason is capable of making decisions: and this is a rare quality today.

The taping of the opening show of the 1963–64 series was a shambles. Gleason, always reluctant to rehearse, was plagued by an infection (“I’ve got a boil”) and spent a short time in the orchestra pit directing his permanent stand-in, Barney Martin, in the blackouts and sketches. He’s more of a stage manager than a director, concentrating entirely on props, sets, lights and cameras; and God help the staff if any of these aren’t precisely the way Gleason wants them.

Then he scattered a few rounds of shrapnel in a tough, carny voice that contrasted strikingly with the modulated diction he used in our conversations and went back to his apartment in the Park Sheraton to sit in a hot tub. Miss Honey Merrill, his personal secretary, a lovely girl with beautiful green eyes and magnificent legs, said, “Jack says he’s never nervous, but he always gets a boil in the same place before each new series starts. It has to be psychosomatic.” And off she went to the apartment to nurse him.

The rehearsal continued without Gleason. The dancers went through their routine under the hard eye of June Taylor, a tough, glacial blonde, and her assistant, Jean Philbin (the producer’s wife), a tall, glacial blonde. Philbin himself stood around with the detached charm of a Dublin remittance man. These are the people on the show who are closest to Gleason.

There are 16 June Taylor Dancers, plus a stand-by. At the start of the season. I had watched hundreds of girls auditioning for the three or four vacancies in the troupe, submitting to rigid tests in tap, ballet and modern dance and weeping hysterically when they were eliminated. All this dedication seems to have been wasted in view of the pony-chorus routines with which Gleason insists on opening the show, and which keep my eyes fixed on the television screen in horrid fascination.

Gypsies are the backbone of the musical business: the hardest-working, most talented, friendliest little creatures in the world. They can and will do anything on a show, and do it superbly. Between them, Gleason and Miss Taylor have connived to turn their gypsies into the least-talented, unfriendliest people I’ve ever seen. And they’ve made them snobs, too. Even the stars of the Balanchine company, the greatest dancers in the world, call themselves gypsies.* Shirley MacLaine and Mitzi Gaynor, former dancers, still call themselves gypsies, but not the June Taylor girls. They have contracts, if you please: they’re no longer gypsies—they have status.

[*Ed. Note: Gypsy: Twenty-five years ago, this term referred only to those hoofers who could do anything they were asked to do in a Broadway show; it set them apart from such colleagues as show and chorus girls, who were lucky if they could learn how to walk across a stage without tripping or to kick high. Today, most dancers are gypsies. They can do anything—tap, toe, modern—while their gorgeous one-track colleagues have just about disappeared from the theater.]

The girls do numbers with canes, stools, brooms, golf clubs, fruit baskets, fruit boxes, anything topical. They form fours in various military formations. They sprawl on the floor in circular patterns for an overhead shot. They climax all this with a straight line of precision high-kicking à la the Music Hall Rockettes. The house comes down; the groundlings cheer; and Gleason enters. But it might easily be forty years ago.

Miss Taylor says. “I don’t look for particular types. All my girls must have slim, trim figures, long, slim legs, attractive faces, personality and ability to dance. They must be fresh-looking, alive and pretty.”

Miss Taylor says that Gleason has a lot of taste in dancing. “For this show he prefers tap and bright, colorful things that are active, full, exciting.” She also insists that Gleason never kibitzes the choreography, but Milt Sherman, her rehearsal pianist, reports, “Sometimes when I’m just noodling around on the piano, June will start improvising some great new routine. She says, ‘That’s wonderful. Milt. What is it? Let’s use it.’ And I shake my head. ‘The tempo is too slow, June.’ Jackie wants fast up-beat tempo always, and it’s impossible to choreograph to that. But he’s right. This is the only way to generate excitement in the audience, and it generates it in him. too.”

Gleason returned to his dressing room a few hours before the show and began private rehearsals with Barbara Heller, Alice Ghostley, Horace McMahon and Frank Fontaine. It turned out that these sacred rehearsals were nothing more than line-readings. As usual, Gleason had everybody’s lines gripped in his iron memory. Downstairs, the bright sound of Dixieland filled the house as Max Kaminsky and his combination, specially hired to fill stage-waits in the taping sessions, began serenading the audience.

“I found out a long time ago, never fight a legend, it’s a losing battle.”

The Scotch appeared, and Gleason began drinking. He sat in a blue bathrobe, bottle and glass in hand, staring down at the table with opaque eyes. The bleak dressing room lounge began to fill with people: Honey Merrill, two or three agents from General Artists Corporation, a jewelry salesman, Gleason’s daughter, Geraldine, and her husband. Jack Chutuk, press agents and assorted hangers-on. In the dressing room proper, Michael, Gleason’s valet, and Ed DeVierno. his dresser, prepared the costumes.

Half-hour was called. Gleason shut himself in the inside dressing room and got into his first costume. An aisle was cleared for him. He came out like a Sherman tank, and you had the impression that if anyone got in his way he’d be trampled under. He had a drink in the wings while the announcer onstage coached the audience, asking for an ovation on Gleason’s catch-phrase, “How sweet it is,” and for whistling and cheering on “And away we go.”

The stage manager held up the slate before the camera and announced Take One. The show started. Ten seconds later they blew the take when a camera began fluttering. In the wings, Gleason bellowed. “Bring me another drink, Charlie, they’re not ready yet.” The audience roared. Kaminsky’s combination played until the cameras were ready again and was sadly cut off in the middle of a great trombone solo by Jack Teagarden. They blew Take Two. Gleason hollered. “I’ll have another, Charlie.” More laughter. When the stage manager announced Take Three, Gleason shouted. “I don’t believe it.” They blew Take Three. Gleason shouted. “Get rid of Charlie.” The audience screamed, the dancers applauded. On Take Five they managed to complete the opening dance number and Gleason at last made his entrance.

After his first stand-up spot he came back into the wings where his valet was waiting with a drink and his dresser was holding his next costume. Gleason had a drink, changed, had another belt and stood, glass in hand, leaning against the stage doorman’s cubicle as though it were a bar, staring down with a set face. He continued drinking throughout the faltering taping to the exhausting end, two and a half hours later.

Outside of being for free, why do they come: and why do 20,000,000 people watch this macédoine of drunk jokes, cop jokes, fat jokes, baggy-pants jokes? It must be pointed out that this clowning is brand new to a younger generation and, perhaps, nostalgic for the old-timers. Also, low comedy has always appealed to a certain class of the public (even Shakespeare heeled about it), and why not? The groundlings have their rights, and if they enjoy watching clowns slipping on banana skins, they ought to be given the opportunity.

But here we come to the crucial question: Why is there such an enormous audience for second-rate entertainment in America, where most adults consider themselves to be intelligent, sophisticated people and would knock you down if you suggested they were groundlings? Why do the Gleasons, the Lawrence Welks and the Beverly Hillbillies clobber all opposition and drive their betters off the air? What has happened to American taste?

The answer is: Nothing has happened to American taste; it has been permitted to stagnate in a mire of self-congratulation. Ours is a mass-production company which is dependent on mass consumption, and for three generations the high priests of mass consumption, the newspapers, magazines, movies, radio and television, have toadied to the mass taste. The common man has rarely been challenged and given a chance to enlarge his horizons. On the contrary, he has been petted and cosseted and encouraged in the delusion that what he likes is not only right, but the very best.

Thinking people are aware that the arts are an active partnership between artist and public. The public must make as great an effort to receive as the artist makes to give; otherwise it cheats itself. You get exactly as much out of the arts as you put into them; and if there is great art available for your enjoyment, you’d be a fool to deprive yourself out of laziness. But three generations of tailored, bite-size, instant entertainment have left the American public juvenile, slothful and smug, a perfect audience for Gleason’s Raree Shows.

He was wearing a citron-colored sweater at our next meeting in the office and sat, as usual, staring down at his desk. I realized that he rarely looks at anyone. Even in his crowded dressing room he looks out into space when he says, “Give me another booze,” or “Give me a cigarette.” He cannot or will not relate to anyone, and you wonder what he’s concealing. Then you wonder if, like the character in Willie Collins’ Woman in White, he’s guarding a secret that doesn’t exist.

I asked him about his drinking and got an odd series of inconsistencies in reply, almost as though previous interviews were confused in his mind.

“I don’t drink anymore,” he said.

“I saw you drinking through the first show. Now wait a minute. I can understand that because I’m a writer, and many’s the time I’ve drunk my way through a tough story. It keeps your energy and enthusiasm going.”

He shook his head. “I didn’t drink for any reason at all. I just drank because I wanted to.”

“All right, if you’re not drinking anymore, why all that hollering to Charlie? Are you trying to perpetuate the legend?”

“I found out a long time ago, never fight a legend, it’s a losing battle. No, I did that because it keeps the audience amused, and keeps them wondering what you’re going to be like when you come out. They’re at a peak for your entrance.” He stopped and stared down at his desk.

“Then do you—”

”I don’t want people judging my drinking by their capacity,” he continued. “I drink for only one reason, to get loaded. That’s all. Sometimes I say I’ve got another reason; because it removes warts and puts an aura around the face. I drink not for what it does to me; for what it does to other people. It makes girls beautiful.

“The only reason people drink,” he went on, “is to change themselves, to become another person. If anybody says he drinks for any other reason, he’s kidding himself. A man comes home from the office after a hard day and wants a drink to relax and forget about it. He wants to stop being that man in the office and become someone else.”

We discussed parapsychology. He said, “Dr. Rhine [J. B. Rhine, noted Duke University parapsychologist] is a good friend of mine, a very brilliant, determined, dogged man. He’s proven that there is such a thing as telepathy, and that’s a pretty big step.” He said that he’d experimented with telepathy himself and had had some success. We went on to hypnotism.

“I’m very good at hypnotism,” he said, “but I never do it for fun.”

“Have you ever been hypnotized yourself?”

“No, I’m too analytical.”

He talked about narcosynthesis, LSD analysis and hypnotism in analysis. I asked whether he’d ever been in analysis.

“My doctor suggested I try analysis to lose weight, so we made an appointment, and an analyst came to my apartment, and when he walked in he weighed 280. I asked him a few questions and he left.” He smiled. “I guess he didn’t think I could do anything for him because he didn’t come back next week. I should have known something was wrong when he came to my apartment.”

“I’d like to see the apartment.”

“Why? It’s just an apartment.”

“I want to look at your books.”

“There aren’t any there. They’re all up at Peekskill.”

“At Round Rock house? May I see that?”

He shook his head and mumbled that he was sorry, but he never permitted reporters to enter his house. He rarely allows any people of any description to enter his house. Gleason never entertains at home, preferring to give occasional parties like Tammany Hall outings at Toots Shor’s in New York and Chasin’s in Hollywood. A former associate says, “He doesn’t know what it is to socialize. He hasn’t been to the theater in three years. He never goes to a ball game, to the fights, anywhere, even on the Toots Shor cultural level. He never has people to his house for anything. He just goes home, gorges himself with food and is alone.”

Gleason replies, “Where the hell would you go if you do go out? To a nightclub to see acts you’ve known for 20 years? That’s no entertainment. And if you’re going out to get loaded, you don’t want to drink in a nightclub. There are too many strangers around, the drinks aren’t so good, and they’re badly served.”

“But why not entertain at home, Jackie?”

“I don’t have to, because I keep running into my friends all the time.”

Gleason’s hotel apartment is merely an ultra-private office where he can work in solitude, so the drop-ins come to Studio 50. But the awkward thing about these occasional visits is the fact that Gleason is working there, too. Get him out of the studio or office into a nightclub, a saloon or one or his rare Tammany blow-outs, and he becomes as genial, witty and personable as a politician, and those who can be snowed by a politician believe he’s a great guy and a warm friend. But the minute Gleason goes to work, he reverts to type. He becomes the tough shell around a psyche which I have not been able to penetrate.

“I’m always suspicious of passive people,” he told me. “All life is based on antagonism. If a tooth falls out of the bottom of your mouth, the one on top usually falls out, too. It has nothing to oppose it. The same is true of muscles and opinions.”

It’s interesting to note that this altitude is reflected in his sketches. No aspect of love or tenderness ever appears in any of them. The comedy of The Honeymooners was based on the perpetual bickering of a man and his wife. The lovers, Arthur and Agnes, spend night after night on a tenement stoop, while Arthur quarrels with the world, and never once exchange a kiss.

He made his other attitudes clear in the course of our talks in the orchestra pit and his dressing room. About his cocky attitude, he said, “Vanity is an actor’s courage. It isn’t built by success. If he waits for success to bring vanity, he’s cooked. He must start with vanity. It kills me when an actor starts off claiming he’s humble, and hiring a press agent to prove it.”

About his know-it-all attitude: “Sometimes I stop a rehearsal. Something’s wrong. I don’t have the faintest idea of what I’m going to say when I get there, but when I do, I have the answer to what’s wrong.

“When I first got Broadway parts, I’d go into the theater and watch everything—props, carpenters, scene painters, wardrobe, the guys in the pit, everything. It was the same thing when I first got into pictures. I’d watch everything.

“So when I yell ‘Hold it’ and walk from that spot in the pit up onto the set, all those years have gone through my mind, and the computer comes up with the answer. The difference between the people who are suitable for their professions and the people who aren’t is that little light that comes on when you see a problem ahead.”

And, a trifle bitterly, about his public image: “Whenever a writer writes about me he immediately becomes an analyst. But what bugs me is when I’m misquoted and then they analyze what I didn’t say.”

“How have they analyzed you?”

“They analyze me by their capacity for life. They say I’m a glutton. They say I’m a drunk. They say I have no regard for money. In fact, the reason I get rid of money is because I know how to regard it.”

“Did people ever ask you what you’d do if you were rich?”

“They’ve asked me that.”

“What was your answer?”

“The only answer is, you’d have more room to do what you’re doing. Instead of a rowboat you’d have a yacht.”

The last time I saw him was the night be broke his wrist. I was in a theater across the street when his press agent tore in during the intermission, looking for a public phone. He told me about the accident and I ran over to the dressing room. Gleason was sitting at the table in front of the TV screen, his left arm resting on a seat cushion, waiting for his doctor. The usual crowd was gathered, none looking particularly agitated. I sat down alongside Gleason and expressed sympathy and my concern. Still there was no contact.

“Give me another booze,” he said to no one. A drink was placed in his hand. He called Frank Fontaine to him. “Frank, you may have to take over for me, so go easy, huh? Lay off the booze.”

Fontaine nodded. I asked how the accident had happened. Gleason told me that he hadn’t been satisfied with a blackout in which he ran a bike into a brick wall made of Styrofoam.

“It was all right,” Honey Merrill insisted.

“It was not all right,” Gleason snapped. “I braked before I hit it. It was all wrong.”

The reporters arrived and questioned him. The two takes were run off on the screen. Gleason was right. He had obviously braked on the first take, but the second was horrendous. The entire wall collapsed on him. Styrofoam may be very light, but a wall twelve by six by a foot is a lot of Styrofoam, and his dedication to detail had earned him a broken wrist.

“Jack,” I said, “you ought to show both takes next week.”

“Mbrrghh,” he mumbled.

This is the baggy-pants extrovert of public appearances and the withdrawn, ungiving creature of private life. To me the essence of Gleason is the fact that he would protest the word “ungiving.” He gives enormous sums to charity, he puts boys through college, he gives a dozen roses to each of the June Taylor Dancers after every show, he pays unstinted salaries. He has the reputation of being the most generous of men. True, but he gives everything except himself. I believe he has no self to give.

Many people have tried to explain the vacuum within Gleason. Most of them attribute it to his Catholicism, toward which he professes great sophistication, and yet which tears him to shreds inside. His feelings about his religion will not permit him to divorce his wife and remarry. I cannot accept this. I know too many Catholics who have made some kind of peace with the conflict between the Church and the 20th Century without being eviscerated.

I prefer the explanation of another poor boy who struggled up from the slums, coped with his Catholicism, a broken marriage and a precarious career in the entertainment business. He says of Gleason, “This is a man who needs love. I don’t think he can recognize it anymore because he never had it. If you don’t have it in your youth, you’ll never know it.”

[Photo Credit: Wikimedia Commons, NYPL]