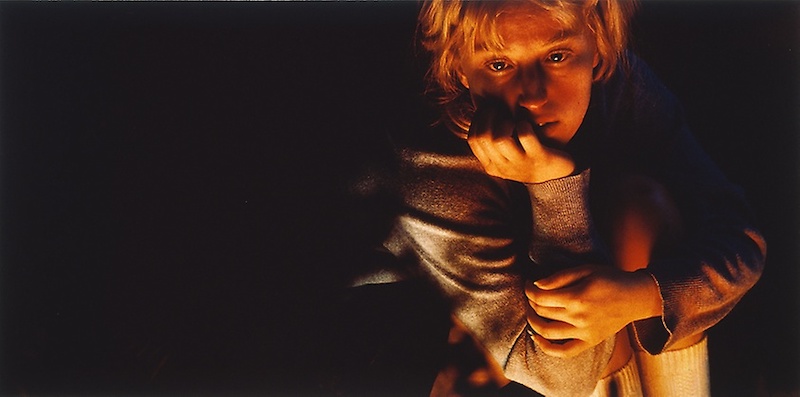

“Are you safe?” is what she always asks the children. It is what she asks the exhausted little boy who has just driven nonstop with his mother from New Hampshire to Atlanta in a rattling VW bus; what she asks the hotel-bound boy whose last vestige of a normal childhood is a collection of Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles; what she asks the boy with the ancient eyes who sits in a restaurant and begs incessantly for a glass of strawberry milk. “Are you safe?” she asks them, and when they shake their heads no or stare at her in confusion, she draws them to her and says, “O.K., darling, it’s all right, we’re gonna make you safe.”

Safe. It is Faye Yager’s word, her chant and rallying cry, and yet it often seems like an incongruous tic of her vocabulary: This is a woman who craves risk and danger. If you seek her help—if you are a woman who has accused your husband of sexually abusing your children and cannot find satisfaction in the courts—she will meet you in a cheap motel or a bus station, some bastion of anonymity, and purge you of who you were and what you had: your name, your history, your friends and family, your Social Security number, everything. She will provide you with a new resume, a new birth certificate, and send you off to live among strangers in a string of safe houses in a country no longer quite your own—in a place Faye Yager calls “the underground.” And if she believes that you have sexually molested your own brood, she will accuse you loudly and fearlessly, on TV and in print, oblivious to lawsuits for libel and slander, pointing a finger until she has divested you not only of your children but also of what remains of your reputation.

She makes her decisions—whether a man is a molester, whether a woman is on the level—in a snap, sometimes just by reading the look in someone’s eyes. She is quick to judge, perhaps because she has nothing but contempt for the judiciary; and she is comfortable in the role of avenger, perhaps because she herself was violated so long ago when she accused her husband of molesting her daughter and wound up in a mental ward. She is resolute in almost everything she does; and she is obsessive in pressing her case that America has given up its children not merely to individual deviates but to a conspiracy of satanists—preachers and politicians and mafiosi and Masons—bent on stealing souls. For this reason she has become an icon among fundamentalists, though she is herself no ardent churchgoer. They believe in her, even now that her romance with the media has ended and reporters constantly attack her credibility, even now that the law has charged her with one count of kidnapping and two counts of cruelty to children—the children of a woman who wanted to go underground and then wanted out.

She is, then, a figure of faith, a woman whose actions tend toward the symbolic, whose journeys tend toward pilgrimages. Last summer, along with two other women, she went on one of her pilgrimages, traveling in a van from Atlanta to Sarasota, Fla., to see her first husband, the man she once accused of molesting her daughter, go on trial for having sex with a 13-year-old girl. Vindication, she said. Justice at last, she said. She did most of the driving, stopping in doughnut shops, at pay phones along the highway, her dress flying as trucks whipped in and out of the night. A friend carried a purse full of quarters, and again and again she would ring into the underground from some shadowy outpost, asking, “Are you safe?” and then disappear into the darkness.

The ladies are lost. All day long they’ve been having adventures, and now, looking for one more, they’ve got themselves lost in Macon, Ga., on a Sunday afternoon. Why, less than a half hour ago, these very same ladies were climbing a barbed-wire fence in a futile attempt to get into some evil old buzzard’s trash, and then they were snooping around a back alley, straining to find occult symbolism in obscenities spray-painted on Dumpsters and warehouse walls. They were just warming up to infiltrate a Masonic orphanage—where they’re certain that children are turned into Satan’s servants—but now they realize they’ve lost their way and have to pull their van into the parking lot of a Baptist church that’s just releasing its flock from the last Sunday service.

The church is red brick, with white trim and a high white steeple. It could be any Baptist church, anywhere in the South, but wait … there is something about it, something about the people streaming this very moment from its doors. “Oh, God, Faye,” says one of the women in the van, a woman with white hair and a nearly white face who, if it weren’t for her pallor, would be a dead ringer for Mayberry R.F.D.’s Aunt Bee.

“Oh, Vicki, do you think?” Faye Yager asks, turning toward Vicki Karp, her Bible-toting companion, a woman with a daughter and grandchildren in Faye’s underground.

“What’s the name of this church? I’ll bet … Oh, God, it is. It’s that church,” Faye says solemnly. Then, with a little squeal of pleasure, she takes the van for a lap around the parking lot, until she meets a crowd of churchgoers and comes to a dead stop. The churchgoers stop, too, and look curiously at the van with the blackened windows. They cannot see inside, so they do not see Faye Yager, the veteran of Geraldo and Inside Edition and just about every other media outlet on earth, sitting behind the wheel in judgment, her mascaraed eyes like bruises, her mouth pinched in contempt. No, what they see is a customized, wine-red, gold-trimmed Dodge Ram rigged with special antennas and an alarm system and fancy alloy wheels and God knows what other accoutrements, and so for a few moments they stop and stare, until they accept the van’s presence or just lose interest.

Faye Yager the most visible link in a network called the Children of the Underground, formed to hide children from sexually abusive parents and the American justice system.

Then the van starts rolling. Faye’s foot is on the gas, and people have to get out of the way, the plump burghers in golf shirts and pastel pants and madras button-downs and white belts and shoes. It’s a congregation with a sartorial debt to Pat Boone, but Faye has a gift for seeing what’s not readily apparent, and besides, this is the church of a man she has accused of sexually abusing his children in satanic rituals. “This is the most evil church y’all have ever seen,” she pronounces cheerfully, although a court called her charges baseless and lawmen snatched the man’s children from a safe house in South Carolina and returned them to Macon.

“Look at them staring,” Vicki says.

“Homosexuals, queers, the whole bit,” Faye says. “Look at that guy in that blue T-shirt over there. I’ll bet you he’s as queer as a two-dollar bill. The way he walks … Look at that guy in that red T-shirt. You don’t think he ain’t queer? See that blue shirt? He’s queer, too, I’ll tell you right now.”

“How do you know, Faye?” asks Faye’s sister Mary, sitting in the back of the van.

“I can just spot them a mile away. The way they walk. They walk like they got a corncob up their behind.”

Faye turns the wheel and heads for a parking lot on the other side of the church. As she drives through the lot, the congregation keeps staring, and Vicki and Mary get nervous. “Faye, where are you going?”

“Faye, let’s leave!”

“Y’all calm down, you’re just too excited, goodness gracious,” Faye says almost giddily as she slips the van in front of the church’s back door. “If you want to see, go inside that door there. Go down those stairs, and you’ll see the altar where they performed the sacrifices.”

“Faye, they know who you are, you can’t go down there!”

“Faye, please leave now. Faye!”

But Faye just laughs, holding on to the moment, at once a lady, prim and proper in a print dress with a white-lace bib collar, and a little girl pleased by her capacity for mischief.

“She used to watch scary movies and make me hold her hand when we were kids,” says Mary, as Faye finally steers the van away from the church. “Now, instead of watching them, she’s creating them.”

Five, six, seven, eight hours later, Faye Yager is still on the road, just she and the trucks and the predawn haze oozing past her headlights. She never gets tired, this woman, she never stops, and nobody could stop her now anyway, not on the sweetest journey she has ever taken, her last chance to settle the scores of all those lifetimes before the new scores started rolling in. Faye Yager, who was once known as Billie Faye Durham, who was once known as Billie Faye Jones, who was born in West Virginia approximately 42 years ago, the fourth of 11 children, as Billie Faye Wisen. What was it, 17, 18 years ago, when she first told people that she saw her two-year-old daughter, Michelle, stroking the penis of her husband, Roger Jones? They called her crazy then, but tomorrow in Sarasota, Michelle is scheduled to testify against her father in his trial for a “lewd, lascivious or indecent act upon a child”; and so this morning Faye loaded her van with some videotapes, some video games, a couple of dozen dresses, her cosmetics, her jewelry, her hatboxes and about 10 boxes of shoes, and together with Vicki and Mary hit the road.

Of course, Faye’s appetite for adventure and intrigue being what it is, she got sidetracked in Macon, and then in Valdosta she visited another sister and drank some white wine—“the cheaper the better.” Now it’s one o’clock in the morning, and Sarasota is still four hours away. Faye, however, doesn’t care one bit about the time. This whole trip, you see, is sort of a last binge for her: When she returns to Atlanta she has to prepare herself to go on trial for allegedly kidnapping and terrifying the very children she has sworn to protect. Besides, she hardly ever sleeps anyway, hardly ever eats, except for doughnuts and fast food, and now she’s getting a little spooky with her sister’s wine—“I’m facing sixty-three years in prison, honey, I may as well get drunk”—and telling the story she tells to anyone who will listen, the story that turned Billie Faye Wisen into Faye Yager, tabloid heroine. It’s a sordid tale, though, and when she recites it her eyes go dead in their bony sockets, her face sharpens into a blade and her hillbilly twang—the one that transposes all her vowels, turns “me” into “may,” “think” into “thank”—trickles from her tight little mouth in a parched whisper, the whisper of someone who knows how to tell a ghost story.

Like a lot of good ghost stories, this one starts in the mountains, in the “hollers” where Faye grew up, a wild little beauty who got baptized in a creek, got kicked out of dances for doing “the dirty dog,” got married when she was 17 because her father wouldn’t let her wear a miniskirt and Roger Jones came around in a car with mag wheels. She didn’t even sleep with Roger on their wedding night, she says, because she didn’t know she was expected to; instead, she slept in the same bed with the girlfriend who stood up for her at the ceremony, and it took a week for Roger and Billie Faye Jones to consummate their union. That was Faye’s first life, and it ended when she saw her husband’s penis in her daughter’s hand—a vision that Roger called a delusion, that caused Faye to attempt suicide, and that eventually landed her in a psychiatric unit.

Her second life began with electroshock and Thorazine and, for all practical purposes, nearly ended with a doctor who diagnosed her as a paranoid schizophrenic. She was just three days short of being committed to the Georgia state mental hospital, she says, when salvation arrived in the unlikely form of John Durham, another patient, her “knight in shining armor,” a gambler, alcoholic and drug addict who called Faye’s daddy in West Virginia and told him to get on down to Atlanta and wrest his daughter from the clutches of the psychiatrists (who, to this day, seem to be the only people Faye truly fears).

Released at her father’s insistence—and against medical advice—Faye divorced Roger, lost custody of Michelle in a jury trial and then defied the court order, fleeing with her daughter. When she found out that the child had gonorrhea, she returned to Atlanta, certain that no court would rule against her now. She was mistaken and ended up spending a brief time in jail, while Michelle went with Roger to Florida. Faye married Durham, but by then Michelle was lost, gone, learning to be the daughter of Roger Jones and to reject her mother. Faye tried to get her back, tried and tried, and when she decided to divorce Durham, whose background was always used against her, Durham shot himself in the head. So she married Durham’s doctor, Howard Yager, and her third life began, a different sort of life this time, with real-estate investments and a Rolls-Royce and a big house and social obligations and her own business as an interior decorator.

Then one day in 1987 she read about a Mississippi woman serving time for secreting her children away from her husband. Faye didn’t know why, but she had to call the judge to give him a piece of her mind. The judge told her she knew nothing about the facts of the case, and Faye, in answer to some need inside her, went to Mississippi for the trial, warning Howard that “he knew he didn’t marry no Donna Reed.” And indeed, it was in Mississippi that she finally met the women who cheered her when she stomped and screamed and went wild; there that she launched an ad hominem attack against the D.A. and discovered the joys of battle; there that she reinvented herself once again as the most visible link in a network called the Children of the Underground, formed to hide children from sexually abusive parents and the American justice system.

She was ready, ready to unleash herself upon the world. She had always been, in her words, “a bitch on wheels,” and now she was wired for sound. Right away, she became a star: One time, when a Hollywood actress went out with Faye to meet a mother on the run, Faye had to warn her, “This mama ain’t here to see you, she’s here to see Faye.” She had her public now, the desperate mothers she met in the cheap motel rooms, the desperate grandmothers—“grannies,” Faye calls them, or “my grandmamas”—who lost daughters and grandchildren to the underground and then put themselves at Faye’s service, learning how to fudge resumes and forge birth certificates and carry clandestine tape recorders. Forever on the road, Faye traveled with wigs and fake credit cards and a fake police badge, giggled about all those times she outwitted the FBI and the Mafia and the Masons, and all in all acted as a curious amalgam of Joan of Arc, Blanche DuBois and Nancy Drew—at once a martyr, an actress, a snoop, a shrew, a fabulist, a glamorous and feminine presence, a merciless avenger and a symbol of womanhood wronged. Indeed, Faye loved to go to piano bars and request “Another Somebody Done Somebody Wrong Song,” or “Memory” from Cats, or “Don’t Cry for Me, Argentina” from Evita, the play she’s seen three times. Like Evita, Faye can’t help herself; everything she does plays to a cult of personality. Even last April, when she was arrested—after a woman named Myra Watts auditioned for the underground and then complained to the cops that Faye wouldn’t give her kids back and had terrorized them in interviews—the arrest became her passion play, since she was apprehended on Holy Saturday and released at sunrise on Easter Sunday after vomiting blood.*

“Oh honey, I’m telling you, I’ve been to hell and back,” Faye says.

Two o’clock in the morning, Sarasota still three hours away. Vicki, one of Faye’s grannies, one of the 150 or so women who came to her preliminary hearing waving Bibles, is asleep in the backseat. The van is quiet, too quiet for Faye, so she picks up the handset of her CB radio. “Breaker, breaker,” she says into it, bryker, bryker, sweetly, cooingly. And then: “This is Billie Hot Pants, and I just want to tell you it’s getting hot in here!”

“Faye,” says Mary, her voice a rising note of caution.

A trucker comes on the band, chuckling. “Well, Billie, heh, heh, maybe you could pull over, and I’ll see what I can do for your problem.” Then out of the blue he asks, “Are you safe?” and Faye’s eyes come back to life with the same look they had in the church parking lot, and she starts flicking her bejeweled hand and laughing in short, high, coquettish bursts: Ah-ha! Ah-ha! “Oh yeah,” she says finally, “I’m safe. And I’m hot! I’m slicker than a minnow’s pete!” Sleeker’n a minner’s payt.

“A what?”

“You know, a minner’s thang.”

Faye is laughing so hard she can’t even talk, and Mary grabs the handset. She’s two years younger than Faye, with a short blond perm and a softer, less biting twang. She’s always had to be more responsible than her sister, and now she says, into the static, “We’re the Children of the Underground.”

“Uh-oh,” the trucker says.

“Do you know what that is?”

“No, ma’am.”

“We take children who have been sexually molested and make them safe. Would you like to help?”

“No, ma’am,” the trucker says, “but I’ll shoot the sumbitch who molested them.”

“Oh, I like him,” Faye whispers.

At 10 o’clock Monday morning, Faye enters the courthouse in Sarasota, the same Spanish-style courthouse where she once conducted some of her battles for Michelle, and goes upstairs to watch the trial of Roger Jones. That’s all she’s supposed to do: watch. She is not a witness, and she has promised the prosecutor that she won’t make any scenes, do anything to compromise the case. She just wants to sit in the courtroom, she says, and “scare Roger Jones to death.”

She is perfumed and powdered and perfectly coiffed, her short auburn hair curved across her forehead, nothing out of place. She wears a beige print dress, beige pumps, pearl earrings and a flat-brimmed straw hat trimmed with a black ribbon. “Faye,” she says, “is known for her hats.”

She has the eyes of a woman who talks always of the devil, rarely of God; always of revenge, never of mercy.

For the first day of the trial, the hat she has chosen makes her look innocent and almost childlike. “Good,” Mary says. “Let that pervert know what he’s been missing.” For the second day, though, Faye wants something darker, more tragic—“I’m gonna lower the black veil tomorrow, honey, I’m gonna hang some crepe”—and for the third day, the day she expects Roger to be sentenced, she wants “something fabulous, maybe something with a feather in it, and really do him in.”

She is sitting in the back row of the courtroom, flanked by Vicki and Mary, when she realizes that Roger Jones won’t be so easy to scare, shame or do in. A man walks into the courtroom from a door behind the judge’s bench, a man wearing handcuffs and a blue jumpsuit with the word JAIL across the back. He is as white as a grub worm, with an enormous white forehead, a mustache, glasses and what’s left of his hair combed across his scalp. He is carrying a Bible. He has not seen Faye in years, and yet he finds her immediately and does not take his eyes off her. She does not take her eyes off him, either. Roger Jones is her enemy, and she is his. He comes toward her, on his way to his seat. Her head jumps back a fraction, and she swallows. Hard.

“Oh, God,” she whispers when he sits down with his back to her. Her chest rises and falls, her fingers go to her throat, manicured fingernails against pale pink skin. “Oh, God.”

For the next hour, she gives an exhibition of body language, her legs crossed and circling, her lips trembling, her fingers leaping to her mouth, her neck, her heart. She is waiting for Michelle to testify and, not incidentally, waiting for her daughter to show that she has finally rejected her father and embraced her mother. Although Michelle lives in Atlanta, on the other side of town from Faye, she does not often visit her mother’s dark and formal Tudor home. Now 21, she works in an auto body shop and hangs out with mechanics and construction workers. Yesterday she flew to Sarasota instead of driving down in Faye’s van, and this morning, when she met her mother in the hallway of the courthouse, she suffered Faye’s fidgety hug with a smile of indulgence, a smile of composure and control.

Hours pass. Then, as Michelle takes the stand—a pretty young woman in a coral dress whose only resemblance to Faye is in the severity of her eyes—there is a bawling sound, almost a voice. It is Faye’s stomach, and each time it creaks and cries she bends over, her eyes fluttering shut, her fingers spreading over her bosom in an image of wounded propriety. Finally, she turns to Vicki and says, “I think I’m gonna be sick,” and heads to the bathroom, a reporter from the local paper instantly at her heels.

Michelle does not testify. The judge hears her story before a jury has been selected and deems it irrelevant to the trial he is conducting the next day, a trial that hinges upon a single question: Did Roger Jones have sex with a 13- year-old girl? So Faye gives Michelle some folded bills and tells her to buy a dress for the girl, a girl who lives in a trailer park and is now a 17- year-old unwed mother, a dress to “make her look innocent.”

On Tuesday morning Michelle goes to the Maas Brothers department store across the street from the courthouse, but when she comes back she tells Mary that she has found nothing. “That’s because she hasn’t gone shopping with her mama,” Faye says. So, before lunch, she leads Michelle, Mary and Vicki back to the department store and begins whisking dresses off the racks and holding them in front of her, saying, “This thing is right down darling. I would get it for myself. Put that on me, even I would look innocent.”

The dresses are all Faye dresses, floral prints with bib collars. As she models and discards one after another, vamping and giggling like a game-show winner on an insane spree, some salespeople attend to her with looks of alarm, and an old black woman with a crinkled face stops shopping long enough to mutter, “Who the hell is that?”

Michelle is falling farther and farther behind Faye’s rush through the store; after a while she folds her arms and sulks. She does not want to find a dress at Maas Brothers with her mother; she wants to rent a car on her mother’s credit card, go to the mall and then drive off to see her friends in the little town where she grew up as the daughter of Roger Jones.

The daughter of Roger Jones. That fact has always come between Faye and Michelle, for Faye could never really wrest Michelle from Roger, even after Faye learned about money and glamour and power, even after Faye became Faye. She could never erase Michelle’s resemblance to Roger—her wide brow, narrow chin, widow’s peak and small feet—and she could never erase what Michelle had learned from him about the art of manipulation and the laws of complicity and control. No, Faye could never give Michelle what her father had given her, which, strange as it sounds, was power, the license to live as she pleased in return for sex. A tomboy, she cut school when she wanted, wore pants when she wanted, drove souped-up cars while sitting on her daddy’s lap. Then, when she came to understand the perversity of her situation—and that she had the power to expose him—she began to despise him openly. When Michelle ran away from home, Roger called Faye and said he could no longer control her wild child.

Through it all, Faye could only see her daughter as the little girl lost; she continued to send Michelle little-girl dresses, not knowing that Michelle turned around and sold them. Now, at the department store, the little-girl dresses flutter in Faye’s wake like flags, and in despair Michelle finally stops short and moans, “Mom, what do you want me to do?”

Faye turns around instantly, her eyes slits. “Michelle, what do you want? Do you want me to rent you a car, so you can go out with your friends and get drunk?”

Michelle doesn’t answer. She storms out of the store and down a side street, toward nothing, a woman-child who got pregnant at 16, put a baby up for adoption at 17 and enrolled in Alcoholics Anonymous when most of her peers enrolled in college. “I’ve been controlled all my life,” she says, her eyes full of tears. “I won’t be controlled now.”

Mary catches up with her and tries to calm her. “She’s gonna get that car from Mary, I just know it,” Faye says.

“You have to have faith,” Vicki says.

“I only have the past,” Faye says, her eyes absolutely immobile and implacable. “I only have the past.”

The next morning, the 17-year-old girl testifies in a dress that Michelle found at the mall, having driven there in a rental car she paid for on Mary’s credit card. The dress is white and virginal, and on the stand the girl looks shy and unsophisticated. The prosecutor asks a series of clinical questions—“Did Roger Jones’s mouth and/or tongue make contact with your vagina … ?”—and each time she answers yes, Faye flinches. Then the girl steps down, the courtroom goes dark, and the prosecutors switch on a video monitor that only the jury can see but everyone in the room can hear. They plug in a videotape Roger made with a hidden camera, and in the dark there are sex sounds, grunting noises and the voice of a 40-year-old man asking a child, “See, it didn’t take me long to get hard, did it?”

Faye’s crossed legs are swinging again. She seems unable to swallow, and some ladies behind her whisper, “I saw her on 20/20” and “She’s been on all the shows.” Then Faye stops moving, and it is as if she knows what is going to happen next, for when Roger turns around to face her, she is staring right at him, and her lips form three silent words: “You disgust me.”

The tape runs for 60 minutes, and before lunch the prosecution rests. A few hours later, as the jury returns from its deliberations, Faye puts on fresh lipstick. When two bulky female bailiffs take seats across the aisle, a reporter tells Faye why they are there: to restrain her should Roger Jones be acquitted. “Maybe I should leave,” Faye says, and Mary squeezes her hand. She does not leave. She has worn, as promised, a black veil, and when the court clerk pronounces the word “guilty” four times, Faye simply closes her eyes four times behind her crepe and hears her daughter say, in the voice of an unabashed child, “Yes!”

They walk into the hallway, into the heat and the glare of television cameras. Faye pushes Michelle into the light. A reporter asks what kind of sentence she thinks her father ought to receive, and with her dark lips curved into a grin, Michelle says, “He’s a pervert and a sleazebag, and he should be hung by his nuts.”

“Thattagirl, Michelle,” Mary says.

“Oh, isn’t she a devil?” Faye asks proudly. “My mouth is suicide, and that there is suicide junior.”

An old woman answers the door in sweatpants and a T-shirt and invites Faye in. An old man is sitting in a chair, in slacks and a sleeveless T-shirt, zipping up a pair of boots. He looks up and says with a nod, “Faye.”

They ask her to sit down. The woman speaks softly and nervously. “We’ve accepted it,” she says. “It’s been hard, but we’ve accepted it.” The man, silent, gets up to put on a shirt. He has a mustache, sparse hair and an enormous pale forehead. When he comes back into the room, he says, “Let me tell you how we feel about this, so you know. Anything they do to him is too good. If he was a murderer or a robber, I could forgive him. But what he did to those children … I can never forgive him. Anything they do to him is too good.”

The man and woman are Roger’s father and stepmother, Bill and Lucy Jones, and Faye has come to their home, in a town outside Sarasota, to gloat. Oh, she tells them that she is there to inquire about Michelle’s medical records, but long ago, during the fight for Michelle, they fought against her, and she has never forgiven them. Do they know that Michelle remembers Roger molesting her in this very house? Do they know that Roger is also accused of raping a seven-year-old in Las Vegas and of having sex with another 13-year-old right here in Florida? They do? Then maybe they’d like to pose for a picture and show America their sorrow.

They do not want to pose. In fact, Bill Jones gets ornery, threatening to tell the press about the unsavory character of Faye’s ex-husband, John Durham. Faye walks out to the porch, smiling. Bill disappears into the darkness of his home, but Lucy Jones gets up and follows Faye. “What I want to know, Lucy,” Faye says very softly, “is who molested Roger?”

“Oh, I don’t know, Faye.”

“It had to be someone,” Faye says, well aware that it could have been anyone who came into contact with him, even a babysitter. “People like Roger don’t just start molesting kids. They learn how to do it. Who was it, Lucy?”

Lucy’s fingers are trembling at her lips, a not unusual reaction to Faye’s innuendoes. “Well, I just don’t know, Faye.”

“C’mon, Lucy, who do you think it could be?” she asks one more time. Then she says goodbye, climbs in the van and heads back to Atlanta, toward her own trials, her own troubles. But right now, as she gets on the highway, she’s laughing, laughing at Lucy’s trembling fingers, and there’s a brightness in her eyes. “Well, I’ll bet I made someone’s life miserable today,” she says.

Then, suddenly, her eyes go dead again. They are the eyes of a woman who talks always of the devil, rarely of God; always of revenge, never of mercy. She puts on a pair of black sunglasses.

“I’ll teach them to mess with Billie Faye Wisen,” Faye Yager says.

Three months later: on the road again, and on the attack, heading to Florida with her wigs and her grannies, to dig up dirt on Myra Watts, her accuser and, in the minds of Faye’s supporters, her betrayer. Myra worked as a waitress in a Cocoa Beach steak house, and now Faye has been hanging around, sniffing for restaurant rumors and visiting the police station, hoping to find something she can use against Myra. At this writing, Faye doesn’t know when her trial will start, but she does not believe that she will be beaten by Myra Watts—not by this woman with the model’s legs and the haggard face, who wears her bleached-blond hair in a flip. With Roger in jail, Faye has a new enemy now, a woman who, in her opinion, sold herself out to the sinister forces that want to prevent Faye Yager from telling the world what she knows. And what Faye knows is something dear to the heart of every conspiracy theorist: that nothing is as simple as it seems, that everything is connected and that no malefactor can exist in isolation. Faye is sure she is right, that there’s a giant conspiracy afoot, that she is a valuable woman in a country unspeakably evil; others are sure she is wrong, that she is a dangerous woman in a country unspeakably gullible. Right now, though, she’s just somebody trying to beat a rap, and when she comes back from Florida, she is obsessed with Myra Watts, and she can’t help talking about the new information she claims will vindicate Faye Yager once and for all. “Oh honey, don’t you know,” she says with a twinkle, “we always have something cooking.”

[Photo Credit: Cindy Sherman via The Art Institute of Chicago]

* Although Myra Watts filed a petition alleging that she was physically abused by her husband, which he denied, she later dropped the petition and they reached a divorce settlement in which she had custody of the children and he had visitation rights.