It was almost one o’clock in the morning but the scoreboard clock was frozen at 12:21. The last game at Yankee Stadium was over, and nobody was in a rush to leave. Sinatra had finally stopped singing “New York, New York,” and organist Ed Alstrom was playing “Goodnight, Sweetheart.” The home team had won 7-3 in a game that meant nothing in the standings but everything in a deeper, gut-felt way. The Yankees were out of the pennant race for the first time since 1993 yet they had drawn 4.3 million fans. And now as the last of them drifted out of the ballpark, it felt like closing night for a hit Broadway Show.

It was just the clean-up crew swinging into action and a select group of people clinging to the moment—players and their families, reporters, radio and TV personalities, cameramen, front office workers, the grounds crew and cops, lots of cops. People hugged and slapped hands and talked and laughed. Players scooped up dirt and grass and put them in paper cups and Ziploc bags. Grown men had their pictures taken at home plate, on the mound and sliding into second. It was like Never-Never Land—everyone was a child. Why would anybody want to go home, knowing they were the last precious few to soak in the Stadium? They stayed, stuck between history and the wrecking ball, until the head of security announced that it was time to go home.

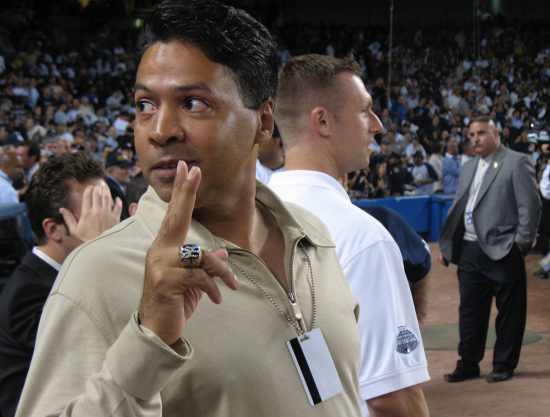

Ray Negron was out on the field, right where he belonged, with the players and sportswriters. Ray had seen them all—from Joe DiMaggio and Mickey Mantle to Reggie Jackson and Alex Rodriguez. He was there when they came to play at the Stadium and he was still there when they left.

He started as a batboy, played briefly in the minor leagues, and ended up as a special advisor whose name doesn’t appear in the media guide. He’s never made much money, just enough to get by. Like so many other boys, Ray grew up dreaming of playing in Yankee Stadium. When that dream died, he improbably became a pet of George Steinbrenner’s and ingratiated himself into the Yankee Universe. He’s one of George’s guys.

“This Stadium saved my life,” said Ray. “The Boss gave me a life.”

Steinbrenner caught him spray-painting the stadium wall in 1973. Ray was with his two brothers and two cousins who managed to get away. Steinbrenner grabbed Ray by the collar and shoved him into a cell normally resolved for drunks and brawlers. The ball park cops laughed at him. But ten minutes later, the Boss returned and made him a batboy. He was going to work off his punishment. Ray’s brothers and cousins took another path. His brothers were undone be heroin and later crack—caught up in the street life. And in less than fifteen years his cousins were dead—one murdered, the other a victim of a dirty needle.

“When my cousin was sick with AIDS,” said Ray, “he told me, ‘You were lucky you got caught.’ I live with that.”

Ray is long and lean and looks like a former jock. He has short black hair and skin the color of café au lait. His large, liquid brown eyes and long eyelashes are almost feminine; his cheeks sag—the sign of a thin man growing older—and lend a sense of gravity to an otherwise boyish countenance. He is not embarrassed to be known as the batboy, does not find it ill-suited to a man of 52. He knows that his fairytale story isn’t just his own.

“The Stadium has been my cocoon,” said Ray. “I can come here late at night, work out in the weight room, or just go and sit in the dugout and clear my head. It’s been here for me almost my whole life.”

And this past summer, he got to share it with Ricky, his 13-year-old son. Ray rented the top room of a townhouse owned by a friend in the South Bronx, a ten-minute drive from the Stadium. When school was out Ricky stayed with him. “You know how kids love the idea of being in the ‘hood’,” said Ray. He wanted to be close to his father and they both wanted to be close to the Stadium, where they went late at night. Ray pitched BP in the indoor cage and hit Ricky fly balls in the empty, semi-dark outfield. He had a broken left ring finger and a sore shoulder as a result. But it was worth it. It makes you wonder how he ever left in the first place.

“‘If I’m the King of New York,’ Reggie would say to me, ‘then you’re the prince of the city.’”

Ray has been an actor and a sports agent, as well as an advisor and a liaison. He has been a confidante, a sounding board and a whipping boy to some of the biggest egos in the game—Billy Martin, Reggie Jackson, Doc Gooden, Darryl Strawberry, Robbie Alomar. He is the Zelig of the Yankees, a witness to some of the great events of the Steinbrenner ERA. When Reggie Jackson hit the third home run in game six of the ’77 Series, it was Negron who, with the presence of mind and crack timing of a Broadway stage manager, whispered in Jackson’s ear and nudged him out of the dugout for a curtain call.

“‘If I’m the King of New York,’ Reggie would say to me, ‘then you’re the prince of the city,’” said Ray. “And I was.” It is one of Ray’s favorite moments.

When he was gone from the Stadium, Ray had a walk-on in The Cotton Club and tried out for Miami Vice. He worked out of his basement representing Juan Beniquez and Jose Rijo and didn’t hold a grudge when they left him for bigger agents. He moved around, was a general manager in the short-lived Senior League, then worked as a liaison with the Yomiuri Giants escorting American players to Japan several times a year. It was good training for the years he spent watching over Doc Gooden and Darryl Strawberry.

When the Cleveland Indians were interested in Gooden, scout Tom Giordano told general manager John Hart not to sign the pitcher without Negron. “I wanted Ray almost more than I wanted Doc,” said Giordano. Team psychologist Charlie Maher used him as go-between with the Latin players like Manny Ramirez, Danny Baez and Robbie Alomar.

“I consider him a baseball guy,” said Hart, who used Ray in a similar capacity with the Texas Rangers. “He has a feel for baseball, a feel for people, a feel for the troubled player. There are so many dynamics in pro sports, and only a portion of it is connected with a player’s talent.”

Ray returned to the Yankees in 2005 and ever since has carried the vague title of advisor. The role is ephemeral, like Negron himself. He has written two children’s books for HarperCollins which he brings with him on visits to hospitals and boys and girls clubs around the city. He is the star of his own reality show, giving personalized tours of Yankee Stadium to sick kids and rich kids, to executives and celebrities, a history of the place according to Ray. His favorite stop is the holding cell where the Boss left him.

“George was larger than life,” said Ray. “Most people can’t sustain that. They have moments of grandeur maybe but are not true forces of nature. George was relentless about building a winner. Less than one hour after the Yankees lost in the first round to the Mariners in 1995, he was on the phone with me and said, ‘Meet me tomorrow morning with Doc Gooden.’ Most guys feel sorry for themselves that soon after a defeat. George was already in action.”

If Steinbrenner was an avuncular presence in Ray’s life, the Stadium was a second home. Ray made sure to spend as much time as possible at the park this season. One night in the hitting cage, Ricky asked him, “What are we going to do next year?”

“That’s when it hit me that the Stadium is really going,” said Ray. “I told my son that I’m going to be the last person to hit a ball in Yankee Stadium. Then as I got in shape, I became more confident and I said, nah, I’m going to be the last one to hit one out. I’m in denial right now about the end of Yankee Stadium. But tonight, at 2 a.m., when everyone is gone, I’m going out there on the field and hit the last home run at Yankee Stadium.”

Ray had arrived five hours before game time in a white stretch Jeep limousine along with a group of young players, mostly rookies and marginal relief pitchers. His last official duty of the season was to chaperone the group to a tribute for fallen police officers in Queens. When he walked inside the Stadium, a few thousand fans were in the stands and the Yankees were taking batting practice. Ray walked down the front aisle, a press credential hanging from his neck, and onto the field.

“Let’s try to be a family today,” said Ray. “I told Randy Levine and Brian Cashman today they’re not my bosses,” he said referring to the president and general manager of the Yankees. “I went to a wake yesterday for a friend who died of cancer. I knew her from the Doc Gooden days. Today is another wake. I don’t want to see anyone angry today.”

“Reggie kicks everybody’s ass but not mine. If after all these years I didn’t know how to deal with Reggie I feel sorry for me.”

Joe Morgan chatted with Derek Jeter behind the cage, then had his picture taken with Robinson Cano. Reggie Jackson, looking fit in a white shirt and slacks, stood next to Val Kilmer, round around the middle, decked in a Yankee cap, aviator shades, blue blazer and jeans. Ray would not be needed by Mr. October on this night.

“Reggie kicks everybody’s ass but not mine,” said Ray. “If after all these years I didn’t know how to deal with Reggie I feel sorry for me. Hey, Reggie walks with Val Kilmer but I walk with Richard Gere. I’m giving him my last tour today.”

Spike Lee.

Ray is not famous, but like most famous people he has an almost compulsive need to be accepted. “My greatest goal would be to win an Oscar,” Ray said once. “It doesn’t matter what it’s for—acting, writing, directing, producing. I just think that would be the ultimate. An Oscar. How much bigger does it get than that?”

Ray’s phone chirped: Willie Randolph. He listened for a moment and said, “Just wear a suit jacket, that way you can just take it off when you put the uniform on.”

Ray likes his famous friends. They give him validation. “I babysat for Ken Griffey Jr, Barry Bonds, the Alomar boys, Sandy and Robbie. The White Sox were in town last week and someone was goofin’ on me and Griff says, ‘Hey, get off my babysitter.’”

Scott Clark from Eyewitness News was waiting for Ray outside the Yankee locker room with a cameraman. They made their way down the busy corridor that runs up the first base line. Ray moved quickly and seemingly without effort, he glided. He’s deceptively fast—if you don’t pay attention you could fall behind easily. Every ten paces someone stopped to say hello, an electrician, a reporter, one of the carpenters. He slapped hands with one of the bat boys, gave a playful shove to Robinson Cano and told the security guard sitting in front of the indoor hitting cage that he’d be back when the game was over.

Around the corner from the hitting cage was a large, unremarkable storage room filled with boxes of blue replacement seats. In the middle of the room was a column with three painted figures: Gehrig, Thurman Munson and Derek Jeter. In 1973, his first year as batboy, Ray was asked to look after Lou Gehrig’s widow during Old Timers’ Day. She told Ray about the place in a back storage room where her husband would go to pray after he discovered that he was ill in 1939.

“This isn’t on the official Yankee Stadium tour,” said Ray, “because they say it isn’t a documented fact, so it’s not officially recognized. But Lou Gehrig came in here to meditate by himself. How is that going to be documented?”

Ray finished with the TV guys and his phone chirped. Richard Gere had arrived. Aris Sakellaridis, press credential in hand, was waiting just outside the Stadium when Gere’s Escalade pulled to the curb. Aris, 47, a good-humored, square-jawed man who grew up in Washington Heights, calls himself a “Ghetto Greek.” He was decked out in a white Everlast track suit with a black fanny pack. A retired prison guard with a steady pension, Aris does some writing, plays semi-pro baseball, and mostly, hangs out with Ray. He’s Ray Negron’s Ray Negron.

Gere and his friend and their two eight-year old boys hopped out of the black SUV and followed Ray and Aris into the Stadium. Gere looked younger than 59, his face open and unguarded. The two boys were excited and physical with each other, in the affectionate way of pre-pubescent boys who are over-stimulated. Ray explained how he met Gere on the set of The Cotton Club.

“He was the waiter,” said Gere.

“I was the waiter,” said Ray.

Richard Gere with Ray in the background.

Ray took them onto the field to see batting practice and introduced them to Joe Girardi, Bobby Abreu, Derek Jeter and Willie Randolph. Then it was on to the blacked-out seats in center field and Monument Park. After that came the indoor hitting cage where Aris tossed the boys BP. When they arrived in the Gehrig room, the boys were quiet and respectful as they listened to Ray’s story, a more detailed version of what he’d told earlier. But this time, he wasn’t talking to a local TV station, he was talking to a movie star. As Ray spoke, he looked into Gere’s eyes and delivered a relaxed, unhurried, emphatic version of his tale. Without saying anything, Gere brought out the best in Ray just by listening. Gere has always been an unselfish leading man who is willing to let his co-star shine as he did with Julia Roberts in Pretty Woman. At this moment Ray and Gere were equals.

After he delivered the Gere gang to their seats, Ray went downstairs and slipped into the Yankee locker room. Less than a minute later he came out with Derek Jeter’s autograph on a small glove, “for a sick kid with cancer that I’m going to visit this week,” said Ray. A man in a suit approached. Next to him were a cameraman and a sound man.

“Ray, Ray, we need you to show us the room. Can we get you now, real fast, Ray?”

Bobby Abreu and Richard Gere.

“Where you been all season? Five minutes till game time and you need me. You must be hitting the bottom of the celebrity barrel if you need me.”

Ray waved his hand and started walking down the hall. “This isn’t an official tour,” he said. “Gere was still the last one.”

Ray’s phone chirped. “It’s Darryl Strawberry.”

Ray grabbed a box lunch from the spread in the hallway and ducked into the auxiliary locker room where the Yankee old-timers were staying that night. Ray said that Darryl was upset not to be at the Stadium. “The Mets are giving him shit about coming here so he stayed away.”

The locker room was empty except for clubhouse man Lou Cucuzza, a heavyset guy with a sympathetic face who has been with the Yankees for thirty-two years. He was sitting on a chair near the back of the room, looking up at a small TV set that hung in the right hand corner of the room.

Ray sat in front of the locker closest to the TV, the locker that was David Wells’ for the night. He ate a chicken sandwich, while out on the field the retired Yankees were introduced to the crowd. The crowd noise was muted by the audio feed from the TV which came directly from the P.A. as if Ray were sitting in a coffin.

“Can you believe Sparky isn’t here?” said Cucuzza. “No Mickey Rivers either. I had 70 guys in here for Old Timers’ Day. Got less than half that tonight.”

Ray, sandwich in one hand, cell in the other, shook his head.

When Thurman Munson’s son trotted on the field, Ray said, “He’s big like his dad but he looks like his mother.”

“You remember Thurman, Ray,” said Cucuzza. “He was rough with the press. He wanted them to think he was mean, but he was a sweetheart in the clubhouse.”

“The best.”

Ray stood up, dumped what he hadn’t eaten in the garbage can and walked out of the locker room. He passed the press room and the Yankee clubhouse, then turned left down the corridor that led to the dugout area just north of the Yankee bench. The sound of the crowd grew louder. Ray moved past the cameras, up the steps and stood on the field where everything was loud and alive, 56,000 people on their feet. Spike Lee was a few feet away snapping pictures. Flash bulbs popped all around the park like a convention of fireflies. Ray stood on the sidelines, arms folded, nonchalant.

Babe Ruth’s daughter was wheeled in front of the pitcher’s mound where she threw out the ceremonial first ball. The crowd cheered as the players—Yogi Berra and Jorge Posada, Tino Martinez and Moose Skowron—made their way back to the dugout, laughing, slapping each other on the back. Bernie Williams walked with his arms around Abreu and Cano. Ray bumped fists with David Wells, said hello to Dave Winfield and then hugged Bobby Murcer’s son, Todd, who was on the field with his sister and his mother. Ray escorted the Murcers upstairs to the loge level, through the crowd to the Elston Howard Suite. The room was boisterous and cheerful like a family reunion.

Ray hugged Catfish Hunter’s widow and then Diane Munson. The players’ wives had always treated Ray like a kid brother when he was a batboy.

“Thurman will be in my next book,” Ray whispered in Diane’s ear.

“That’s sweet, Ray,” she said. “Do you miss him?”

“Yeah, I miss him.”

The game unfolded in a blur for Ray. He brought Todd Murcer and Munson’s daughters to the Gehrig room for one last tour and then hung out in the press box for a couple of innings. He commiserated about the end of the Stadium with Goose Gossage and helped Elston Howard’s daughter look for her purse. When Mariano Rivera trotted to the mound in the top of the ninth, Ray walked through the crowd on the field level to the front row, next to the TV camera stationed behind home plate. Rivera retired the Orioles in order and the game was over. It had been dull but the Yankees had won and the fans were happy. Jose Molina hit the final home run in Yankee Stadium, securing his name in trivia history. Ray stood on his chair as the crowd cheered and Frank Sinatra’s rendition of “New York, New York” amped up the volume.

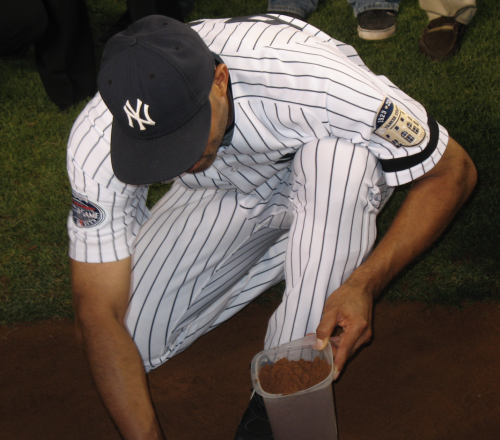

Mariano Rivera collection dirt from the mound.

The Yankee players gathered on the field. Hundreds of cops did as well. After a few minutes, Ray moved across the first aisle toward the Yankee dugout, past police commissioner Raymond Kelly and finally to the end of the row, where Rudy Giuliani and his wife Judith smiled at him. Rudy patted Ray on the shoulder and opened a little gate so that Ray could get onto the field. Ray crossed in front of the dugout and stood with the other clubhouse employees along the railing. “New York, New York” played again and again. The players congregated in the middle of the field and Derek Jeter gave a tactful speech of appreciation. With the crowd roaring, the team took a lap around the field saluting the fans and then leisurely drifted toward the dugout, waving to their families in the stands, Sinatra still singing. Ray hugged Bobby Abreu and said, “I’m proud of you.”

Ray sat in the dugout, Jeter signing autographs just above him, dozens of photographers snapping away. Ray’s phone chirped: Robbie Alomar. A compact man wearing a warm-up suit over his uniform sat down next to Ray and shook his hand. It was Caesar Prescott a scout for the Yankees, and Ray’s batting practice pitcher for the night.

Less than an hour later, when the reporters had finished getting their locker room quotes, Ray went into the weight room carrying a black bat, autographed by Pudge Rodriguez, sticky with pine tar.

“It will be at least 2:30 before we can get out there on the field,” said Ray. “At least. I can’t go out there if people are still around, especially the head of the grounds crew ‘cause he’ll rat me out.”

Aris swung a fungo bat and Caesar tossed a small medicine ball against the wall. Ray put on warm-up pants, a pair of sneakers and two batting gloves. “The last time I took BP was in 1980,” he said. “It was the year that Graig Nettles had hepatitis. The team was on the road and he was here taking batting practice one day. I was able to sneak in there and get a couple of hacks. I went up there hitting like Reggie, but from the right side. I had Reggie’s stance, his whole act, down cold. I got a hold of one and hit it out. I go into my whole Reggie, trotted around the bases and everything.”

Ray started peddling casually on one of the stationary bikes.

“And as a bonus,” he said, “the ball almost hit Pat Kelly, the Stadium manager, who was sleeping in the seats out there in left field. He was a mean dude. Nobody liked this guy. The ball landed right by his leg. It didn’t hit him, but it woke his ass up. Right then I vowed, ‘I’ll never take another swing at Yankee Stadium.’ It was a perfect moment. And I haven’t taken another swing. Not until tonight.”

Ray looked at the writer who had been trailing him all day and said, “Do you think I can hit one out?”

“Does it matter? You’ll be the last guy taking batting practice.”

“You’re right,” said Ray. “Hear that, Aris? I should enjoy myself.”

The three men went down the hall to the indoor hitting cage. Ray and Caesar stepped inside. Ray’s first couple of swings were rusty. He dropped his hands and lunged at the ball. “Okay,” said Caesar, “here comes another one, let’s go.” After about ten swings Ray started to make solid contact, yanking the ball high into the screen. Caesar said, “C’mon, attack the ball. Be aggressive. Let’s go.”

Ray got into one.

“Home run,” he said. But it wasn’t the one he wanted. He finished the round and helped Caesar pick up the balls. Then he took another round and sat on the bench as Caesar pitched to Aris. Ray closed his eyes. The security guard stuck his head in the room and said, “Ray, they are still out there. You should just go home.” Ray nodded at him. Soon, he was slumped over, sound asleep, his bat in his hands.

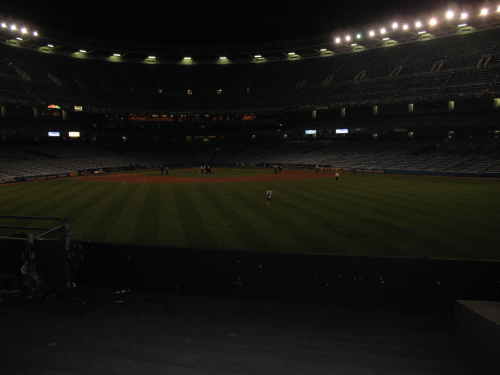

At 3:00 a.m. two dozen people were still hanging out on the field. The main Stadium lights had been turned off, but the back-up lights were on, making it visible but dim on the field. A chubby kid who looked like Mickey Lolich pitched off the mound, surrounded by six packs of beer. He drained a beer and then filled the bottle with dirt. In the upper deck, Stadium workers used leaf blowers to clean the aisles and the seats, and a steady buzzing sound filled the park. It was chilly now.

As Ray napped in the hitting cage and then in the weight room, Caesar hit fly balls to Aris in the outfield. At the break of dawn, only two people were left on the field: the head of the grounds crew, a short, blond man, who stood like a weathervane on the mound, and a tall drink of water in black whose flowing hair made him look like a heavy metal guitarist. It did not look like they were going anywhere.

Caesar was ready to surrender. “Let’s go,” he said to Aris. “It’s over.”

They returned to the weight room. Ray sat up on the massage table.

“It ain’t happening,” said Aris.

“They ain’t leaving, Ray,” said Caesar. “They’re going to be here until seven in the morning.”

Ray shrugged and gave a half-smile, his face puffy with sleep.

Caesar said goodbye and Ray packed his bag. A few minutes later, Ray and Aris left the weight room.

“Let’s give it once last look,” said Ray.

They walked down the corridor to the camera pit, up the steps and out onto the field. Other than the few dozen people left in the stands cleaning, everyone was gone. The field was empty. Ray turned to Aris.

“Even if I only get three or four swings before someone comes to kick us out, at least I made the effort,” said Ray.

“Let’s do it.”

Aris grabbed the bucket of balls, Ray grabbed the bat and they walked back out onto the field. It was almost six in the morning. Dawn was turning the sky from dark blue to gray. Aris took the bucket of balls—twenty-two in all—to the mound and began to stretch. Ray put on his batting gloves, took a few practice swings and stepped into the batter’s box. The buzz of the leaf blowers was the only sound in the park. Aris held up a ball and Ray nodded. Aris kicked his leg and delivered the pitch. Ray took an easy swing and hit a ground ball to third base. Aris held up the next ball and threw. Ray hit a pop-up into the seats by third base.

“OK, here it comes,” said Aris, “Big stick.”

Ray hit a line drive and grunted on his follow-through. He got under the next few and hit more pop flies. He let a pitch go by. Ray’s swing was tired. Then he hit another line drive, this one with some distance.

“There you go. That’s what I’m talking about,” said Aris.

Ray tried to jerk everything in the air to left—a line drive, a foul ball into the seats, a fly ball to short left.

“That’s it,” said Aris.

Aris had a rubber arm. He’d struck out fifteen in a semi-pro game two days earlier, but he was giving Ray pitches to hit. With six balls left in the bucket, Ray hit a fly ball to deep left. “There you go, baby,” said Aris.

The ball sailed toward the seats but curved foul. It cleared the fence but in foul territory.

“There it is,” said Aris.

“No, no. It’s got to be legit,” said Ray, digging his right foot into the batter’s box.

Two pitches later, Ray hit another fly to deep left. He didn’t hit this one as well as the foul ball, but it traveled all the way to the wall and bounced off the Cannon sign.

“There you go, baby,” said Aris. “Five extra push-ups and that’s going over.”

When the bucket was empty, Ray dropped his bat and walked to the outfield with Aris to gather the balls. A few minutes later, he was taking more cuts. But Ray could not hit another deep fly ball. He hit grounders and let out soft grunts after each swing. A line drive, a pop-up. With each passing swing, Ray’s body began to sag. He was spent. When the bucket was empty, Ray exhaled.

“That’s it, man, I’m done.”

Aris said, “One more round, c’mon.”

“My groin is going to give. I don’t want you carrying me off this field.”

“Ten more, just ten more.”

“No, that’s it. I’m done.”

Ray kicked at the bottom of his bat and looked up at the sky.

“Ray, we can come back another day and do this,” said Aris.

“Let’s pick up the balls,” said Ray.

“Leave them out there.”

“Nah, we have to hide the evidence.”

The two men walked slowly to the outfield and picked up the scattered balls. Ray moved gingerly, his head down, discouraged. He felt numb. After all his planning, after months of practice, Ray had come up short, five extra push-ups away from hitting one out. There were no witnesses. Even the cleaning crew didn’t seem to notice. But he didn’t hit one out, and that mattered to Ray. The Stadium was closed. The final night was over. Jose Molina, of all people, had been the last man to hit a home run at Yankee Stadium.

“It’s six in the morning, Ray,” said Aris. “You hit the ball good. We’re dealing with old ass BP balls that have been used all season, plus they’re wet with moisture. If we had been out here at Two, you would have been hitting bombs.”

Ray was not listening. “Damn,” he said over and over.

They finally walked back to the infield. A hulking security guard moved toward them.

“Here he comes to throw us out,” said Ray.

When the guard reached them, Ray and Aris stopped walking. The guard looked them over and said, “Do you think it’s okay if I have one of those balls?”

Aris gave him two.

“I thought you were going to kick us out,” said Ray.

“I’m not going to throw you out,” the guard said. “You’re Steinbrenner’s guy.”

[Photo Credit: AB]