Art Schlichter is scrambling. Running late, headed from his father’s farm in Bloomingburg, Ohio, to the Springfield Antique Show and Flea Market, he flips on his Road Patrol XK radar detector and hits the gas, challenging the two-lane road, sliding into the wrong lane to take a blind curve. A farm truck appears dead ahead. With all-pro reflexes, Schlichter whips the car back into the right lane just as the rig blows by. “Did that scare you?” he asks his passenger. “It scared me.”

But he recovers quickly. “Was that my fault?” he asks.

Schlichter parks the car at the flea market. As he walks up to the family booth, he can hear his father: “If Arthur were here, where he’s supposed to be,” Max Schlichter is saying, “we’d be all set up. But he’s sleeping in somewhere.” Art starts to unload a van by grabbing two fake Christmas trees, both missing branches, and sticking them under a tent. “People here,” he says, “will buy anything.”

Though he stands 6-foot-2 and weighs more than 300 pounds, Max Schlichter doesn’t have the handshake you’d expect. Thirty years ago, he grabbed a hunting rifle by the muzzle, banged it against the tractor he was riding and shot a bullet through his palm. Last year, bad weather and falling prices forced him to sell his farm so he could plant corn, soy and tomatoes on 4,200 rented acres. Back when his son was a National Football League quarterback, Max figured Art would one day buy the family farm.

Once the vans are unloaded, the tables set up, Art gets itchy. But with thousands of people pouring in, driving out isn’t easy. He gets lost on a dirt road that cuts around the funnel-cake stands, past a guy in an “I Buy Bicycle Lamps” shirt and through the crowd. Suddenly, a woman steps in front of the car. When she looks up and sees Schlichter bearing down, she starts to shimmy like fresh Jell-O, part of her body going one way, part the other. Just as Art finds the brake, she aligns her limbs and leaps to safety. “Whoa,” he says, checking the rearview mirror, “scared the shit out of her.”

After lunch, Art stops by his brother’s house, where one of his little nephews comes to the door with a new, spiked haircut. The spikes take Schlichter by surprise. “You’re a farmer,” he says, “not a punk rocker.” He tosses a football with the boy, whose eyes take on an unmistakable glow.

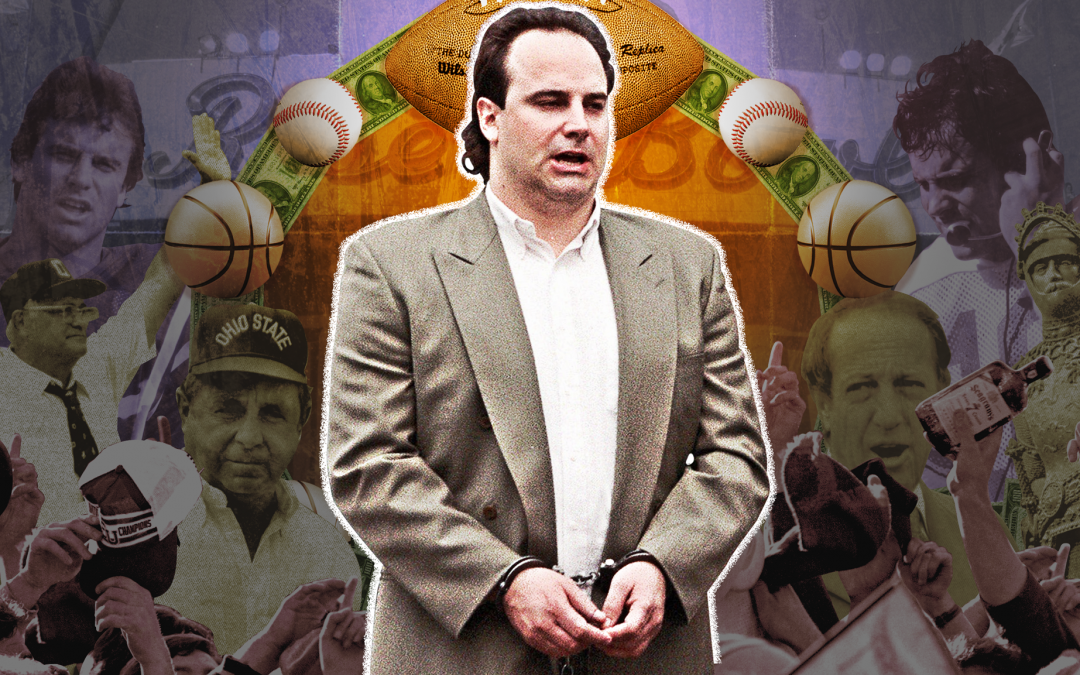

It’s been five years now since Art Schlichter was first suspended by the NFL for gambling. Once the top quarterback prospect in the country, the fourth player taken in the 1982 National Football League draft, he last started an NFL game in 1985. Since then, he’s been cut by Indianapolis and Buffalo and played wide receiver for a Columbus flag-football team. When he tried to come back with Cincinnati last year, the NFL, citing a gambling relapse and his arrest in Indianapolis, suspended him again, so Schlichter took a job at VanLand, a Columbus dealership that claims to sell more vans than any other dealer in the world. He was so good, they made him a closer. “I’m a natural salesman,” he says. “I can sell the sleeves off a vest.”

Nonetheless, when the Ottawa Rough Riders of the Canadian Football League offered him a reported $25,000 bonus and $125,000 contract this past spring, Schlichter quit. Ottawa’s coach, Fred Glick, didn’t promise Schlichter he would start, but Glick made him feel wanted—something Schlichter hadn’t felt for a long time, not since high school. Today, even in Columbus, where he starred for Ohio State, still does charity work and still has many fans, there are those who consider him a spoiled kid who had everything, everything, and blew it. “The person on the street is sympathetic,” says an Ohio State booster. “He fired up the Buckeyes, and he beat Michigan. But I don’t think people that were close to him have much respect for him.”

They used to call him King Arthur. As a Little League pitcher, he twice struck out 18 batters in a six-inning game. In three years as starting quarterback at Miami Trace High School, Schlichter (pronounced Shlees-ter) never lost. He was all-state in football and basketball. Encouraged by his father, who was certain Art would be a great athlete from the time he was four, Schlichter trained religiously. During the summer, to strengthen his arm, he would throw 2,500 passes a week. In one drill, he lofted the ball 50 yards, over an 18-foot net, while seated on the ground.

Miami Trace’s “Hall of Fame” is an Art Schlichter shrine—his jerseys, his trophies, and the team pictures with the cheerleaders kneeling at his feet, Art’s hands on the shoulders of the girl he dated. “Close friends of mine always accused me of being hung up on him,” says Bill Hanners, then Art’s best friend and wide receiver. “There were times when I’d just stand around and watch him and think, How’s he do that? I’ve wished a lot of times that I could be like him. It just seemed there wasn’t anything he could do wrong. Everything he tried, he did well—and at the same time, he had to look like a goddamn model.”

Miami Trace is less than 40 miles from Columbus. The largest metropolitan area in America without a major league sports team, Columbus takes the fortunes of the Ohio State Buckeyes seriously. Downtown, across from the State Capitol, is a hundred-year-old church with a huge stained-glass window above its front door; pictured in the window is Ohio Stadium, home of the Buckeyes, former home of Woody Hayes.

The legendary coach, who was revered in Columbus long after he resigned in disgrace, won his first national championship at Ohio State six years before Schlichter was born. By the time Schlichter reached high school, Hayes, who died last year, had immortalized his plodding three-yards-and-a-cloud-of-dust offense and his coaching creed: “When you throw a pass,” he loved to say, “only three things can happen, and two of them are bad.” Together, Woody and Art would discover a fourth thing.

Hayes disdained hotshot quarterbacks, but it’s hard to ignore the best in the country when he’s playing in your backyard. An OSU assistant coach, George Chaump, eventually sold Woody and Art on each other. “I liked the idea,” said Schlichter, who succumbed to pressure from friends, relatives and Buckeye loyalists everywhere, “of an Ohio boy turning the Ohio State offense around. I wanted to be the one to make the Buckeyes pass.”

His freshman year, 1978, Schlichter beat out a senior incumbent who had been all–Big 10. Then he threw five interceptions in his first game, and Woody rediscovered the run. “You run a stupid-ass pass attack,” says Chaump, now head coach at Marshall University, “and you’re going to get intercepted. I recruited Art, and I felt bad morally. I think there was a breach of contract.”

King Arthur had his own fan club. He had to move out of his dorm because girls he’d never met were knocking on his door all hours of the night.

The season ended with a loss to Michigan and a trip to the Gator Bowl, which is about as far from the Rose Bowl as you can get. The game was lost when a Schlichter pass was intercepted and Hayes, already famous for his sideline temper tantrums, punched the Clemson linebacker who had intercepted it. On the flight home. Woody got on the intercom. “This is your coach,” he said. “I won’t be coaching you next year.”

He was replaced by Earle Bruce, the team’s former offensive-line coach, a Woody Hayes wanna-be. The ball stayed on the ground, and the team won. Throwing infrequently but well, Schlichter took the Buckeyes to the Rose Bowl undefeated, playing USC for the national championship. With two minutes left, Ohio State led by six, but the defense tired and the Buckeyes lost by a point. Still, Schlichter finished fourth in the Heisman Trophy voting, higher than a sophomore had ever finished, and he became the favorite to win it the following year. Newspapers and magazines raced to his hometown to photograph him seated on a tractor he probably didn’t know how to start. One pro scout said that had Schlichter been eligible, he would have been the first player taken in that year’s NFL draft. “Schlichter is one of those guys who can turn situations around,” said Gil Brandt, personnel director of the Dallas Cowboys, “like a Bradshaw and a Staubach.”

King Arthur had his own fan club. He had to move out of his dorm because girls he’d never met were knocking on his door all hours of the night. A local sportswriter went to work on his biography. “That he doesn’t drink or smoke isn’t terribly uncommon among athletes,” reported Straight Arrow: The Art Schlichter Story, “but he takes pride in insisting he has never drunk as much as a bottle of beer or sampled any of the drugs now accepted as part of our culture by so many youngsters … if he sounds too good to be real—so be it.”

A warning bell has sounded in Schlichter’s car. It’s a noise he’s never heard before, but it might have something to do with the light on the dash that keeps flashing: “A/C System Problem.” The car, an Olds Toronado, is covered with dirt and dust. Its seat belts—“Nobody ever uses them”—are buried somewhere beneath the trash, the official CFL football and the pile of newspapers. “I like to read the paper while I drive,” says Schlichter.

Though he has all the tools to be a great driver, he has never quite put it all together. In recent weeks, he’s had two accidents—“One wasn’t my fault, and the other one I just hit a slick spot and spun out”—that have left his brakes sounding like a sick cow. “Sounds like $300 to me,” says Schlichter, who recently declared bankruptcy, listing $1,010 in assets and almost $1 million in gambling-related debts. At Ohio State, he kept getting speeding tickets, which a certain judge would dismiss—until the local newspaper found out. One night, the paper reported, Schlichter got a ticket and then, on his way home, got stuck in wet cement. He says the story isn’t true—it was a different night. “I’m not nearly as bad a driver as I used to be,” he says. “I get picked up every now and then, but I really try not to drive fast. You see kids getting killed. My parents always talk to me about that.”

And the radar detector?

“My dad gave it to me.”

The brakes groan as Schlichter pulls into a sports bar down the street from Ohio Stadium. Done in Ohio State’s colors, scarlet and gray, with a Woody Hayes poster on one wall, the place is built like an amphitheater, with the chairs and tables rising in a semicircle in front of three big screens. Right now, King Kong Bundy is wrestling on the first screen, a tape of the NCAA basketball championship is on the center screen, and the Cubs and the Cardinals are playing live on the third. Schlichter turns up the volume on the basketball game—each table has its own speaker—and orders a turkey sandwich. “Boy, you’re pretty,” he says to the waitress. “Are you married?”

Seated nearby, watching the Cubs game, is an OSU alum and occasional golfing partner of Schlichter’s named Billy.

“Are you making any money?” Art asks.

“I hear you’re getting married,” says Billy.

“Who told you that?”

“I hear she’s a fox.”

“Are you still married?”

“Are you kidding? I had to get out of that.”

“What’s your girlfriend’s name?”

“I’m not gonna tell you. You might go snaking around.”

“I don’t do that.”

“Yeah,” says Billy, laughing.

When one of the screens flashes a shot of Bobby Rahal driving at the Indy 500, Art and Billy talk about what it’s like to go to Indy or to Louisville for the Kentucky Derby. “Can you believe I’ve never been to the Derby?” says Schlichter. “I can’t believe that.”

“Next thing you’ll tell me is you never bet on it.”

“Oh, I’ve bet on it.”

Billy reminds Art of a certain night they spent at the track. They grin, then start to laugh. “Do you remember that night?” asks Schlichter. “I think my parents were there that night.” They laugh louder.

The bar is almost empty. Billy orders another drink, Schlichter another Pepsi. “Are you an Ohio State girl?” he asks the waitress. She nods. “Do I have to pay for this?”

Suddenly, the center screen goes blank, and, as if in a dream, the face of Woody Hayes appears. Schlichter sits up straight. “This is great!” he says, turning up the volume, as Hayes stamps angrily toward a cameraman. “Watch Woody! Watch Woody!” The coach unleashes a hook, and the picture spins out of control. There’s also a clip of Woody in a locker room, doing his best Knute Rockne, first telling the Buckeyes that the team that wins today will be the team that hits the hardest, then leading a wild, frothing charge onto the field. “I still get chills,” says Schlichter.

On his way out of the bar, he stops at the men’s room, where there’s a guy standing at a sink. “There’s no soap,” the guy warns.

“I’m not washing my hands,” says Art.

“My mom always told me to wash my hands after I pee.”

“My mom always told me not to pee on my hands.”

Earle Bruce: “I would venture to say that if Earle Bruce had been the football coach in the recruiting of Art Schlichter, he would never have come to Ohio State.”

Schlichter never won the Heisman. While he dreamed of dropping back and launching bombs, Bruce kept calling option plays that took advantage of Schlichter’s speed and running ability but left him battered and unprepared to run a pro offense. The quarterback quietly seethed. He even considered transferring, but the bond with Ohio State was too strong. His junior year ended at the Fiesta Bowl, where he passed the Buckeyes to a 19–10 halftime lead over Penn State. In the second half, Bruce went back to the run, and Ohio State lost, 31–19. Afterward, Schlichter and his dad—who, unlike Art, was openly critical of Bruce—went to a dog track.

Bored, frustrated and never one to lose himself in his studies, Schlichter started spending more time at the track. Even when he was in high school, he had played the horses once or twice a week. Now the wagers started small, but his dad’s farm was doing well, he had the promise of a pro contract, and gambling was the only thing he’d found that could match the high of playing quarterback. The amounts grew. The day before an OSU-Michigan game, he and two teammates won $1,500.

Oddly enough, one of the people Schlichter often found at the track was Earle Bruce. Sometimes they’d eat together or go to the window together. They always got along at the track. “It was probably the only thing we’d ever talk about,” says Schlichter, “when we would talk.”

Max Schlichter: “I know Earle played a part in it, and he knows it. I don’t want to talk about Earle. I want Earle to disappear, and I think he has. [After nine seasons, Bruce was fired by Ohio State last year.] I think Earle’s big joy in life is over.”

Earle Bruce: “At first I felt, Why did that happen? You feel kind of guilty. But I’m not his father. I was his football coach. People try to put the blame on Earle Bruce. They don’t say anything about his religion, his home and everything else. Well, what the hell are they talking about? If my daughter has a problem, I’m not going to blame it on anybody else but myself. I’ve seen [Art] at the track, but what does that have to do with anything? I don’t have an addiction. I sure as hell didn’t bet for him or take him to the window or twist his arm or give him any tips or anything else. I think one time I did offer to take him to the track, and he said, ‘No, I’ll drive my own car.’ But I didn’t see anything wrong with taking him to the track at the time. You don’t think that everybody who goes in a bar is bad. Do you assume that everybody who goes to a track is bad?”

Art Schlichter: “The fact is, he was out there and I was out there. It’s not illegal to go to the track, but, obviously, for me, it wasn’t a good place to spend my college days—and I spent a lot of my college days at the track. I think Earle knew that I was gambling pretty heavy. If he had said bring me some evidence, I’m sure they could have found some evidence that I was gambling.”

Earle Bruce: “I had four meetings with him about things that I heard [rumors that Schlichter was betting with bookies]. Each time, he could look us in the eye and deny that it was going on. If a kid looks at you and says, ‘Hey, I’m not doing that,’ and he really is, I mean, how do you prove it? I had his high school football coach on my staff. I said, ‘My God, if he doesn’t know what’s going on—or his dad—who does?’ He’d been gambling for a long time. I don’t think he wants to admit that. His father took him to Las Vegas. His parents bought him a horse and put him in the business.”

The amounts grew. The day before an OSU-Michigan game, he and two teammates won $1,500.

Schlichter took failures in most of his senior courses and never graduated from Ohio State. When he wasn’t at the track, he was calling one OSU booster and demanding a gin game, always for $100 a hand. “He had this thing,” says the booster, “that he could beat anybody, and he figured the amount never made any difference.” He also bet on football, basketball and even baseball games. “The first day of the season,” says the same booster, “he says, ‘I got these three games—they’re gonna all win.’ Three baseball games. I mean, I am laughing my ass off because I know that he doesn’t know his ass from a hole in the ground. All three of them lose. Okay? Now, I was the one that placed the bets with my people. He lost all three, but he never gave me the money—$12,000. He didn’t have the money. He figured he wasn’t going to lose. He was invincible. I paid it, and I said, ‘Now we’re done, D-O-N-E.’”

The extent of his gambling remained a secret, but by the end of his senior year, Schlichter’s standing with pro scouts had fallen. He had taken a beating, and his passes had begun to wobble. Still, in the 1982 NFL draft, he was the fourth player selected, the first quarterback. Even Schlichter was surprised. He was picked by Bob Irsay’s Baltimore Colts, a bad team with a tight payroll, who chose him over Brigham Young’s Jim McMahon largely because Irsay had had difficult dealings with McMahon’s agent. “Schlichter was drafted by the owner,” says Ernie Accorsi, then the Colts’ assistant general manager. “Those of us in the football business felt McMahon was the only first-round pick.”

In Baltimore, Schlichter was billed as a savior. The Colts had traded away two veteran quarterbacks, Bert Jones and Greg Landry, and his only competition would come from another rookie, Mike Pagel, who had been taken on the fourth round. But Schlichter went to training camp out of shape physically and out of sorts mentally. He’d lost his confidence and he’d lost his girlfriend, who’d had enough of his lying and cheating. It was the first time a girl had ever dumped him. “I am not exaggerating,” says Accorsi, “when I tell you that Mike Pagel beat him out on the first day of practice. It was just no contest.”

For the first time in his life, Schlichter rode the bench. He met a barmaid whose ex-boyfriend was a bookie. Then the NFL players went on strike, and he had nothing to do. Before long, he was gambling $1,500 a week—and gambling badly. Instead of picking his spots, he’d bet 10 basketball games a night. “I would take the money to pay off the debts,” says Bill Hanners, his old high-school buddy. “My wife had a little orange Mustang that wasn’t worth $1,500. We used to laugh at how much money we had in that car over a period of eighteen months—maybe $250,000, easy.”

Schlichter bet a bunch of basketball games one night when Hanners was visiting from Columbus. He won the early ones, but everything hinged on one late NBA game between San Antonio and Denver. For three hours, Schlichter, who had San Antonio and four points, did nothing but call Sports Phone. “I can remember it like it was yesterday,” says Hanners, who, fearing the worst, knowing Schlichter couldn’t cover the bet, went to his room and fell asleep after Denver took a 61–34 halftime lead. He was awakened by a scream. With four minutes left, San Antonio had tied it. Hanners stayed up while Schlichter worked the phone. Eventually, he got a final: San Antonio 133, Denver 128. Ecstatic, and deeply relieved, they went to sleep. The next morning, Hanners caught an early flight to Columbus. “It was real quiet,” he remembers, “everyone on the plane was sleeping. My wife dozed off, and I’m just casually flipping through the sports pages. All of a sudden, I see ‘DENVER 133, SAN ANTONIO 128.’ The guy on the phone had made a mistake. I just yelled out, ‘Noooo!’”

“It got progressively worse,” says Schlichter. “I was totally out of control, scared to death, the whole nine yards. That’s why I didn’t ask for help or tell anybody for so long. I didn’t want it to become public. I didn’t want people to think this guy they thought had it all had a problem.”

Especially his parents. Another night, Schlichter watched a basketball game in the family rec room with his mom and dad, neither of whom knew their son had $50,000 riding on the outcome. With one second left, Geoff Huston of Cleveland went to the foul line. If he hit one of the two shots, Art would win. The first missed. Art said nothing. The second missed. Art said goodnight. He got up, climbed the stairs to his room and vomited for three hours. “The money wasn’t important,” Schlichter said a few years later. “Gambling, betting—that’s what was important. Doing something wrong, something sneaky. All my life, people had been telling me what I should do, what I should say. Do this. Say that. Smile. Sign autographs. Answer dumb questions. Be a good guy. Be a nice guy. Be the straight arrow. Gambling was the one way I could say, ‘Screw it, I can do whatever I want.’ It was my outlet, my release. I got high when I placed a bet. Not when I won a bet—when I placed it.”

He didn’t win many. When he lost, he made larger bets. When he lost again, he got the money—from friends, from acquaintances, from banks. How did he get it? He asked.

Don Mollick, an OSU booster and a friend of Schlichter’s: “Art was never told no. Every time he got in any kind of trouble, somebody was pulling him out of it. He has uncanny control over people, uncanny. And he has unbelievable balls. Art Schlichter could walk in a damn office, sit down, prop his feet up on the desk and say, ‘You know, I could use a hundred grand.’”

Bill Hanners: “He sent me one time to one of the banks where he knew my face would be recognized, with three checks, one for $10,000 and two for $7,500 each. He sent me down there to cash them, and I walked out with $25,000, and he flat out did not have the money in the bank. He had called the president of the bank, who had watched us grow up, and said he would transfer the funds in. I couldn’t believe it. I walked out with $25,000.” The money was never transferred.

An Ohio State booster: “Art Schlichter was the best liar I have ever met, and I’m a salesman. Art told me this story about this girl he had out in California. It was a UCLA cheerleader or somebody. Her family had money, and he was really going crazy over it, and he wanted to buy her a ring. He really needed $3,000, and I told him I’d give him $1,200 of it. And it was bullshit. He didn’t use it for that.”

How do you know?

“I’ll lay you money.”

Some of the money came from his family. “He was taking money out of his dad’s farm account,” says Hanners. “He had put a lot of his bonus money into an account for the farm. Behind his father’s back, he drained it out. That was always on his mind.” Sometimes, Schlichter asked his father directly. “Arthur,” his father told him one time, “I’m giving you this money, and it’s just like taking a part of your mom’s body, because this is the insurance money we got when your mom had cancer.” Art took it and swore he’d never gamble again. And he didn’t—for a week.

The lies got to him. He told Hanners that he’d begun to think everyone might be better off if something happened to him. There were nights when he considered driving his car off the road. “Hey,” Hanners told him, “we’ll work it out. Hell, you’ve borrowed hundreds of thousands of dollars. You can do anything.”

But he couldn’t stop gambling. One week, he won $120,000. The next three days, he lost $200,000. He never recovered. A desperate attempt to win it all back cost him another $70,000. Hanners, using Art’s code name, “Fred,” was making regular deliveries, but Schlichter was down almost $160,000. Finally, one of the bookies told Hanners, “You tell Fred he best have some money next week. He won’t be throwing too many footballs with a broken arm.”

Schlichter went to the FBI. A sting operation was set up, and on April Fools’ Day, 1983, his bookies, lured to Columbus by the promise of an $80,000 payoff, were arrested at the airport—just outside a store displaying a mannequin in an Art Schlichter jersey. In Columbus, there was much speculation as to whether Fred would live to tell his story. But it turned out the bookies were amateurs who weren’t even laying off his bets. Most bookies share the risk; these guys were keeping Schlichter all to themselves. They had found a stooge, a sure thing, a gambler so bad, so frenetic, so illogical, it was almost impossible for him to win. On those rare occasions when he did, they put off paying him and convinced him to gamble some more. They knew he’d lose it back. For Schlichter, learning he’d played the fool was humiliating, but it was better than having his arm broken.

When reporters surrounded the Schlichter farm, Art’s mom draped sheets over the windows. Spotted leaving his lawyer’s office in Columbus, he was asked if he was Art Schlichter. “I was,” he said, “at one time.”

“I’ve never put him down,” says friend Don Mollick. “In fact, if anything, I’ve tried to maintain a sense of humor. I said, ‘Art, anybody can be a goddamn chicken-shit quarterback in the National Football League. There’s a lot of people that can do that. But you know what? You’re the most famous gambler in the damn world.’”

Even after he was diagnosed as a compulsive gambler and checked into South Oaks Hospital in Amityville, New York, for a month, Schlichter, who has been attending Gamblers Anonymous meetings off and on ever since, didn’t really believe he had a gambling problem; he thought things had just gotten out of hand. He says he knows better now. In his betting career, he has gambled and lost more than $1 million, mostly on basketball games but also on NFL football games—though apparently not on games he played in. Schlichter’s affliction, shared by some 3 percent of the U.S. population—1 million to 3 million adult Americans—is increasingly being recognized as a disease. It’s unclear what triggers the disease, but environment and personality are both considered factors. Compulsive gamblers tend to be bright, motivated, athletic, easily bored, easily frustrated, emotionally immature, prone to depression, fearful of rejection and preoccupied with money. They also like action. In high school, Schlichter’s trademark was a quarter that he constantly flipped in the air. “You’d just want to grab it,” says Hanners. “I would always say to him, ‘Would you just talk and stop fucking around with that quarter,’ but he never knew how to relax.”

NFL commissioner Pete Rozelle suspended him for what turned out to be the entire 1983 season. During that time, the Colts moved to Indianapolis, and Schlichter became a born-again Christian. He joined the team’s Bible-study group and became friends with a gospel singer named Sandy Paddy. “Some people,” says Schlichter, “want to be like Bruce Springsteen or John Elway. I’ve had my share of the limelight. I’ve had great thrills, more than most people. I played in the Rose Bowl. I won big games. I made All-American. I made a million dollars. I’ve done everything you could do except be successful as a professional, but there’s much more. I want to be better. Sometimes, I don’t live the life I’d like to live. I cuss some and I’ve made mistakes in relationships, but I think I’ve become stronger and I think I’m building strength. If I could change places with somebody, I think I’d like to be like Sandy. She’s helped me keep my faith in the Lord. She could go secular if she wanted to and probably extend her wealth, because her voice is that good, but she chooses to sing for the Lord, and I admire that. That’s something I’d like to do, to have enough of a relationship with the Lord to go out and spread His word.”

“I got high when I placed a bet. Not when I won a bet—when I placed it.”

The first year in Indianapolis, 1984, Schlichter struggled. The second year, he won the starting job in training camp, and the team’s coach, Rod Dowhower, proclaimed him the quarterback of the future. Then, after one game, Dowhower cut him. He said he’d decided Schlichter didn’t have an NFL arm. People wondered what had happened. “I know what happened,” says Schlichter. “The rumors caught up with me. I had done some gambling that spring—not betting, but going out and playing golf with the guys, and I got off the wagon a little bit, and it hurt me. It caught up with me. He’d told me if he ever heard a rumor, he’d cut me.”

The following summer, Schlichter tried out with Buffalo, but when the Bills signed former University of Miami star Jim Kelly, he was cut. Once again, frustrated, with nothing to do, he ended up back in Columbus. “It was October or November of 1986,” says Hanners. “I hadn’t seen him for six, eight weeks. He pulled up to a phone, got out pen and paper, and he started writing down names and teams. I said, ‘What are you doing?’ He was talking to a fellow in Indianapolis. So I said, ‘What the hell, let me play.’ He handed me the phone.”

This time, it was Schlichter who got stung. When an Indianapolis prosecutor broke open a betting ring, one of the names that turned up was Schlichter’s. Perhaps looking for publicity, the prosecutor chose to arrest the former quarterback. Hanners got the call, too.

“One night, the phone rings,” says Hanners. “‘This is John something from the Indianapolis Police Department.’ It was 11:30 at night. He says to me, ‘Bill, I want you to jump in your car, come over here and turn yourself in.’ They take me downstairs to the basement, fingerprint me and put me in a little holding cell. I don’t drink, I don’t smoke, and here I am in a cell with a lot of lowlifes. There was one big black guy who was on the phone saying, ‘I’d just as soon kill a honkie as look at him.’ I walk around the comer, don’t look up and just sit down and stare at my shoes. All of a sudden, I recognize this voice: ‘Why don’t you get a job, you bum?’ I said, ‘Well, here we are….’”

“Was that illegal, what I just did?”

Art Schlichter has just darted across two lanes of traffic to make a right turn, an illegal right turn. It’s Thursday evening, the Ottawa Rough Riders have just broken training camp, and unless he can get to a furniture store quickly, he’s going to be sleeping on the floor of the townhouse he and his fiancée, Mitzi, have rented. They met on a blind date in Indianapolis, where Mitzi was working as a waitress. “Actually, it wasn’t blind,” says Schlichter. “I went over and checked her out before the date.”

Back in 1982, when Schlichter was a first-round draft choice with a $350,000 bonus and a three-year, $480,000 contract, he flew his mother to Baltimore, and she spent $20,000 stocking his new condo. This time he’s bargain hunting. His paychecks haven’t started yet, and his creditors are after him. “Obviously,” he says, “they’d like to have their money back, and if I can pay them someday, I will, but it’s just a situation that happened. I don’t think the bankruptcy has been finalized yet, but I assume my debts are cleared. You know, I have to be concerned about Mitzi and my family now. That’s why they made the rule for bankruptcy.”

Schlichter finds the store, which he’s been told gives discounts to Rough Riders, in a strip shopping center. “This is the kind of place,” he says, parking the Olds, “where they give you $100 off and you have to make eight commercials.”

“What size bed are you looking for?” asks the salesman, a thin, dark man with a pencil mustache. Schlichter’s mouth opens, but nothing comes out. “King? Queen? Double?” asks the salesman.

“What’s this one?”

“That’s a king-size. It’s our most expensive bed.” But it comes with a special feature. “You see these horizontal strips?” says the salesmen, fingering the top of the mattress. “It’s designed for heavy activity.”

Schlichter looks at something cheaper. “You buy that mattress there,” says the salesman, “and it’ll sag in two years. I’ll sell it to you if you want it, but this one here will never sag.”

“You sound like a car salesman,” says Schlichter, not without respect.

The salesman quotes him some prices—all adjusted to include the Rough Riders discount, but Schlichter isn’t satisfied. “What,” he asks, “if I do eight commercials and seven appearances?” The salesman smiles, but the store isn’t interested. Undaunted, Schlichter asks about credit. No Canadian financing company, he is told, will take on an American citizen. “I’ll have to carry you myself,” says the salesman, perhaps unaware of his customer’s financial history. “I can carry you for two or three months, but I can’t carry you for the whole year.”

“That’s all I need,” says Schlichter. He starts to say a certain Rough Riders executive will vouch for him, but the salesman interrupts. “I’m sure he will,” he says. “If you were a lousy, no-good American, [local columnist] Earl McRae would have written it in the paper.”

“Well,” says Schlichter, smiling broadly, “I am a lousy, no-good American.”

The store’s about to close. “Look,” Schlichter finally says, “can I get a bed, a dresser, some end tables, a couch, a chair and some lamps for $2,000?”

“I think we can do that.”

“Can I get it for less?”

“Now starting at quarterback,” booms the public-address announcer at Lansdowne Park, “for your super-season Ottawa Rough Riders, No. 10, King Arthur.”

It seemed a good match. Schlichter, still only 28, went to Ottawa figuring he’d get some playing time and then maybe one last shot at the NFL. Desperate for star appeal, however tarnished, Ottawa promoted him heavily. The Rough Riders, long the worst team in the Canadian League, were struggling to revive the franchise amid rumors that the team or even the league might fold (things have gotten so bad that two of the eight teams share the same name: the Saskatchewan Roughriders and the Ottawa Rough Riders). On the field and off, Schlichter, people kept saying, just looked like a quarterback.

He started well. Playing half of the last exhibition game, he stirred hopes by completing all nine of his passes for 150 yards. Open and gracious with fans and the press, he quickly won the city and the starting job, but he didn’t win games. Though he threw well at times, he got little protection, and the Riders lost badly. Fearful for his job, the coach, Fred Glick, the guy who’d really wanted Schlichter, panicked and benched him. (Glick was fired anyway, replaced by his brother-in-law.) Though Schlichter stayed on the bench, his teammates publicly proclaimed him the team’s leader. When the losses continued, the fans took to chanting, “We want Art! We want Art!” Eventually, he demanded to be played or traded. They played him. He didn’t do badly, but the Riders lost, and after two games of repeated sackings, he went on the disabled list with bruised ribs.

The day Schlichter was eligible to be reactivated, he was cut. Once again, people wondered. Speculation focused on money (his contract wasn’t guaranteed), on his relationship with the new coach (they hadn’t spoken for weeks) and, inevitably, on gambling. “There have been rumors,” says the team’s general manager, “but it was not a factor. We’ve won one football game this year. When that kind of thing happens, you make changes.”

Schlichter, who immediately retained an agent to put out feelers in the NFL, remains hopeful. “He has to believe in himself,” says George Chaump, the former OSU assistant. “If there were some magic where he could regain that attitude…” Still, he has considered his possibilities. He’s good with kids and might try coaching; he’s done some sales work for an Ohio sports equipment firm called the All American Company; he and Mitzi have discussed opening a Physicians Weight Loss Center; and there’s always VanLand. Of course, returning to Columbus does have risks. When he left for Ottawa, Schlichter said he knew it was time to get out of town. Too many old friends. Too many old habits.

“He’s got it in him,” says Hanners, “just like I do. I’ve been going to tracks since I was three or four years old. My wife works behind the window—in fact, that’s how we met. When I leave here tonight, I’ll probably run out to catch the last three races. I would think Art would have to be tempted almost every day. If I was in his situation, I’d probably have a closetful of hats, beards and trench coats.”

Does Hanners know if Schlichter has such a closet?

“I’d rather not say.”

“The way I answer that,” says Schlichter, “is it’s my business. I have to worry about myself. Whether I’ve made a dollar bet or a $5 bet or a $1,000 bet, it’s my problem and it’s my business. I haven’t made a bet today; I didn’t make one yesterday.”

After he was cut, Schlichter and Mitzi, who plan to marry in January, rented a trailer and packed up their stuff for the trip home, back to Columbus. Art figured he could do the 700-mile drive in 11 hours.

[Featured Image: Sam Woolley/GMG]

[Note: Schlichter was convicted of fraud in 2011 and sentenced to 10 years in prison after he conned more than 50 people out of millions of dollars through a sports ticket scheme.]