On a July evening several days before the opening of the Democratic Party’s national convention in Boston, Arianna Huffington steers Dr. Justin A. Frank through a throng of people packing the hallway of her $7 million Brentwood home into the even more crowded living room. In tan Prada heels, black Armani slacks, and a lime green Valentino top whose plunging neckline shows off a chunky moonstone necklace, the 5-foot-ll-inch Huffington towers over her companion. Not that Frank recedes into the background. White Italian suit worn just so, orange-and-purple striped Etro shirt open at the neck, and all of it set off by a pair of ringtail lizard Lucchese cowboy boots, the professor of psychiatry at George Washington University is as flamboyant in appearance as the thesis his hostess has invited him here to propound. Namely, President George W. Bush is not merely a man whose foreign policy is misguided and whose syntax is garbled. Rather he is, in clinical parlance, a paranoid megalomaniac.

“This is a person who’s got us to live out his nightmares,” Frank insists shortly after taking the microphone. “This is a man who blew up frogs at the age of 12 and who branded the buttocks of frat pledges at Yale with a hot hanger. This is a man who’s tried to manage internal chaos by externalizing it. Instead of learning from his experience, he has us living it.”

Among the 100 or so film industry figures, activists, and reporters Huffington has assembled is a smattering of luminaries. Gazing down from a staircase landing are the author and director Nora Ephron and her author and screenwriter husband Nicholas Pileggi. Leaning against a grand piano (above which hangs a portrait painted by Francoise Gilot, the former mistress of Pablo Picasso) is the actress Morgan Fairchild. Standing near the bleached-wood doorway is the pundit and television producer Lawrence O’Donnell. And perched on a sofa, hands wrapped around a gold-handled cane, is Stanley Sheinbaum. For years, Sheinbaum’s home provided the setting for the celebrity-studded political events that define intellectual life on Los Angeles’s liberal Westside. Now it is Huffington who hosts them. As the journalist Ann Louise Bardach, who is in the audience tonight, puts it, “Arianna is the city’s premiere salonista.”

Indeed, just two mornings earlier, in the dining room across the hall, Huffington had welcomed such progressive Hollywood players as Robert Greenwald, the director of the documentary Outfoxed: Murdoch’s War on Journalism, Shari Foos, a left-leaning campaign donor, and a gaggle of power wives, among them Kathy Freston, whose husband, Tom, is co-president of Viacom. The occasion: a talk by former Democratic presidential aspirant Howard Dean.

That these personages feel at home at Huffington’s inspires the occasional raised eyebrow, for it was fewer than ten years ago that her salons at the mansion she shared with her then-congressman husband in Washington, D.C., drew an altogether different kind of crowd. “Everybody was there,” says Jeff Eisenach, the longtime director of GOPAC, the political action committee chaired by Newt Gingrich, former Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives. By everybody, Eisenach means not just Gingrich but John Fund, a contributor to The Wall Street Journal’s editorial page, Grover Norquist, the anti-tax guru, Laura Ingraham, the telegenic right-wing fulminator, Rich Lowery, soon-to-be editor of The National Review, and such holdovers from the Ronald Reagan administration as Michael Deaver. The agenda almost always featured a discussion of ways in which private enterprise could solve society’s problems. George W. Bush would have fit in comfortably at any of the get-togethers.

Not so anymore. At Huffington’s Brentwood event for Justin Frank, Bush would have felt like a piñata at a birthday party. “His use of language keeps people at a distance and is an impediment to thought,” the professor declares after enumerating some of the president’s better-known malapropisms. “He is fundamentally incurious, and the central reason is that any curiosity would be dangerous because it would lead him to be curious about himself.” There is, Frank concludes, but a single cure—removal from office. With that, he hands the microphone to his hostess, who brings the presentation to its end: “I want to close by quoting my Greek compatriot Socrates, who said, ‘The unexamined life is not worth living.’”

Though a line forms in the dining room so that Frank can inscribe copies of Bush on the Couch, his book-length exercise in “applied psychoanalysis,” it will not be a long night. All eyes are on Boston, and this is especially true for Huffington. She will cover the convention in her syndicated column, which appears in 50 newspapers, and in her blog, and she will comment on it on Left, Right & Center, the KCRW radio show on which she is a panelist. She will also hawk copies of her new book, Fanatics & Fools: The Game Plan for Winning Back America. Then, on the day of Senator John Kerry’s acceptance speech, she will be joined by her daughters, Christina and Isabella, both of whom she wants to witness what she hopes will be the beginning of the end of George Bush’s presidency. Finally, after the last word is written and the last sound bite doled out, she will spend a week vacationing at the opulent Martha’s Vineyard summer house of comedian Larry David and his wife Laurie, a cofounder, along with Huffington, the agent Ari Emmanuel, and the producer Lawrence Bender, of the Detroit Project, which sponsors ads attacking SUVs for their conspicuous consumption of gasoline. The visit with the Davids, while putting Huffington about as geographically distant from Los Angeles as one can get in the continental United States, will rejoin her with the Westside liberal community that now sustains her and of which she has become an unavoidable exemplar.

During this most political of seasons, the Arianna Huffington show has been packing in audiences not only at her Brentwood home (where she’s hosted functions for everyone from Senator Barbara Boxer to would-be first brother Cam Kerry) but all across Los Angeles. They come because she is famous, a figure whose omnipresent electronic reality on CNN and MSNBC enhances her already considerable physical presence—those long legs, that brilliant red plumage, and the unmistakable Greek accent. They come because she is funny (“I was born in Fresno and cultivated this accent so I could be an ethnic minority,” she repeatedly informs audiences). They come because in her recent books—chief among them Pigs at the Trough, an assault on corporate villains that made the New York Times best-seller list in 2003—she reaffirms their view of the world.

Here she is at Trina Turk boutique on West 3rd Street addressing a hundred gay and lesbian activists at a benefit sponsored by the Victory Fund, an organization that helps to finance the campaigns of homosexual political candidates. “Our struggle started with the Emancipation Proclamation and Brown versus Board of Education,” she asserts, “and now it’s the same for gay marriage.”

Here she is at the Beverly Hills residence of Skip Bronson and Edie Baskin, sharing a lectern set up on the capacious back lawn with Joseph Wilson IV, the former United States ambassador to Gabon who revealed on the New York Times op-ed page that prior to the war in Iraq, he’d informed the State Department that Saddam Hussein did not attempt to purchase weapons-grade uranium. To an overflow audience, she enthuses, “We all owe Joe a debt of gratitude.”

“I’m amazed and appalled that these seemingly sophisticated people in L.A. don’t realize who they’re dealing with.”

Here she is onstage at the Skirball Cultural Center, making the case for drug legalization at a fund-raiser for the Drug Policy Alliance, a George Soros-backed organization dedicated to the liberalization of drug laws. “I’ve never smoked a joint,” she tells a boisterous crowd, “but for me, this is a civil rights issue. It predominantly affects African-Americans and minorities.”

Everywhere, Huffington is cheered and applauded. Everywhere, her jokes draw laughter. Everywhere, money is raised ($50,000 at the Victory Fund event, $100,000 at the Drug Policy Alliance gathering). Yet everywhere there is also an undercurrent of, if not quite disbelief, at least wonderment—and not just about Huffington’s mid-’90s enthrallment with Newt Gingrich. Wasn’t it only a year ago, someone will inevitably ask, that there were all those stories?

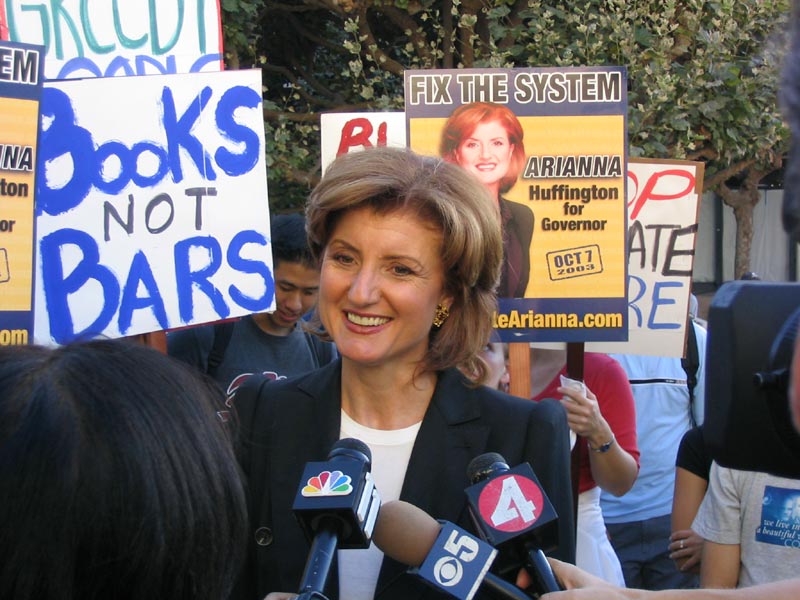

From the moment Huffington literally stumbled into California’s 2003 gubernatorial recall race by knocking over a clutch of microphones while trying to insinuate herself into a photo session with Arnold Schwarzenegger, she came across not as a poised progressive but as something quite different. True, she ran as a populist, vowing to raise taxes on the rich and oust the lobbyists from Sacramento, but less than a month into the campaign, the Los Angeles Times reported that the fabulous trappings of her life notwithstanding, she had paid only $771 in federal income taxes during the previous two years and no state taxes at all. Moreover, the paper revealed that she had claimed deductions of $6,675 for donations to the Church of the Movement of Spiritual Inner Awareness, a Santa Monica-based religious organization founded by a controversial, self-proclaimed divine called John-Roger. Two days later the Times delivered a second blow, reporting that her campaign manager was a lobbyist for several big businesses, among them Lorillard, the cigarette manufacturer. Then, in response to a Schwarzenegger interruption at a critical debate, came Huffington’s loaded comment: “Let me finish. This is the way you treat women. We know that now.” The remark referred to accounts depicting Schwarzenegger as a sexual predator, but far from hurting the movie star, it gave him an unintended opening. With a line that called to mind a scene from Teminator 3, in which his character brutally dispatches a female adversary, Schwarzenegger retorted, “I would like to say that I just realized I have a perfect part for you in Terminator 4.” A week before the October 7 election, Huffington, who’d seen her poll numbers plummet from a meager 6 percent to a nearly invisible 0.6 percent, used an appearance on Larry King Live to drop out of the race.

Thus it was that while Huffington has indeed emerged as Los Angeles’ reigning salonista, she has simultaneously become one of the city’s most polarizing figures.

To her detractors, Huffington is a slippery opportunist driven almost solely by a desire for power. “Arianna,” asserts Los Angeles-based political consultant Bill Carrick, “is one of the most dedicated persons to developing a public profile I’ve ever seen. She’s gone through some remarkable changes, but the one thing about her is that she’s a consistent self-promoter.” Echoing this view is the journalist Maureen Orth, whose new book, The Importance of Being Famous, contains an updated version of a scathing profile of Huffington first published in Vanity Fair in 1994. “I’m amazed and appalled that these seemingly sophisticated people in L.A. don’t realize who they’re dealing with,” she says. “There’s always a very specific agenda to advance herself, and if it’s done at someone’s expense, so be it.” Not unexpectedly, Huffington’s erstwhile allies in the Republican Party are equally harsh. Contends Rick Tyler, the spokesman for Newt Gingrich, “America is a great country, and Arianna has made a living out of having an identity crisis.”

To her supporters, Huffington is an intelligent and committed stalwart in the fight for social justice. Declares the author Gore Vidal, who has known Huffington casually for many years, “The changes she has made in her life are interesting. That used to be known as a sign of growth. So how can you fault her?” The actor and director Warren Beatty is even more supportive: “There’s no question about the sincerity of Arianna’s conversion to being a progressive. She is a person who does not stop searching for solutions. In terms of her commitment to democracy, there is something genetically Athenian in her.” Seconding Beatty’s assessment is Marc Cooper a contributing editor to The Nation who advised Huffington during her shift from right to left: “She wants to make a difference. She’s not just posturing for self-satisfaction.”

The disagreements regarding Huffington will not soon be resolved. As even her friends, quoting a remark about her that originated in the enemy camp, are wont to say: “She is the most upwardly mobile Greek since Icarus.” What is beyond dispute, though, is that the behavior that ignites the disagreements is right out there in the open. “What you see is what you get,” notes a woman who has known her for two decades. Wherever Huffington has lived—London, New York, Santa Barbara, Washington—the triumphs, reversals, and transformations have been visible to all, making her life not so much a mystery to be plumbed as a spectacle to be witnessed. “What’s behind the public persona?” a former friend rhetorically inquires. “More public persona.”

It’s altogether fitting that Huffington’s latest incarnation finds her in Los Angeles. This is, after all, the city of second chances and rebirths, of new beginnings and rejuvenations, of an abiding commitment to transcendence. The only surprise is that Huffington took so long to assume her rightful place.

She was born Arianna Stassinopoulos 54 years ago in Athens and grew up there in straitened circumstances. Her father was a struggling newspaper publisher and womanizer, while her mother was, in Huffington’s words, “incredibly nurturing.” The two separated when Arianna was nine, and she and her younger sister, Agapi, were raised by their mother. By the time Arianna was 13, she was already five feet ten. She wore chunky glasses and stood head and shoulders above her girlfriends. “I was a visual cacophony,” she says. She spent her happiest hours reading and prayed frequently to the Virgin Mary.

When she was 15, Arianna saw a photograph of the Cambridge University campus and said to her mother, “I want to go there.” Though Arianna’s father, with whom she remained close, discouraged the idea, her mother accompanied her to London for oral exams. “We were so nervous,” Huffington says, “and then we got this telegram.” Arianna had been awarded the Girton Exhibition, a full scholarship. At Cambridge, she became the first foreigner (and only the third woman) to be appointed president of the Cambridge Union debating society. At 19, she was paired with John Kenneth Galbraith in a televised debate with William F. Buckley on the merits of the free market system. The political writer and pundit Christopher Hitchens, who was a student at Oxford at the time, says, “She was the first person who made me understand the word celebrity.”

After receiving a master’s degree in economics, Arianna moved to London. There she wrote for Punch and The Spectator and published her first book, an antifeminist manifesto titled The Female Woman, which established her as a controversialist. Equally significant, she became involved with two men who changed her life.

Arianna met Bernard Levin, columnist for The London Times, star of the satirical BBC television show That Was the Week That Was, and 21 years her senior, when they both appeared on the BBC game show Face the Music. After the taping, he invited her to dinner, beginning an eight-year relationship. “He was very brainy, rather conservative, a champion of Wagner, and very entertaining in a witty, double-domed sort of way,” says R.W. Apple, who during the years when Levin and Arianna were together, was the London bureau chief of the New York Times. Opera, politics, wine, the evils of communism, and the importance of good grammar—these were the subjects in which the older man tutored his eager young inamorata. Says Huffington, “I loved him very much.”

Three years after taking up with Levin, Arianna met John-Roger, the cherubic “Mystical Traveler” and head of the Church of the Movement of Spiritual Inner Awareness (MSIA—pronounced “messiah”). Born Roger Delano Hinkins in Utah, John-Roger had been teaching English at a Southern California high school when, while recovering from an illness in 1963, he claimed to have been visited by the spirit of John the Baptist, who bequeathed him life-altering powers. Although John-Roger’s ministry initially focused on “light readings” and “aura balances,” by the 1970s it had acquired the trappings of the self-improvement craze and began offering something called Insight Transformational Seminars. Arianna, who was searching for a spiritual environment less constricting than the Greek Orthodox faith of her youth, was drawn to John-Roger’s seminars—and she drew Bernard Levin with her.

The idea of the cerebral and eminently respectable Levin and his leggy Greek girlfriend chanting New Age mantras and participating in role-playing games appalled British sensibilities. Nearly 30 years later, it still does. In an otherwise reverential obituary of Levin, who died in August, The Guardian reported: “Towards the end of the 1970s, Bernard entered a strange phase. He fell more in love than ever before with Arianna Stassinopoulos … Through her he became involved with an organization called Insight. Part of its ritual was to encourage each other to act out their fantasies. There were stories of Bernard’s dressing in a tutu that boggled the minds of his friends.”

In 1980, Arianna and Levin arrived at an impasse. She wanted children; he did not. As it so happened, 1980 was also the year Arianna published her first biography, Maria Callas: The Woman Behind the Legend. Though Arianna was sued for plagiarism (she settled out of court), the book became a best-seller, affording its author the wherewithal to move to New York.

Arianna set up house in a $50,000-a-year brownstone on the Upper East Side. It was the beginning of the Wall Street boom, and by her own description, she was “this new young thing” in town. She dated powerful men, chief among them the publisher and real estate baron Mort Zuckerman, and her dinner parties, prefiguring much that was the follow, were renowned. Oscar de la Renta, Barbara Walters, and Placido Domingo all came. As a consequence, Arianna had little time to devote to a biography of Picasso, for which, in 1981, she had received a $550,000 advance from Simon & Schuster. “I wasn’t strong enough to get off the merry-go-round,” she later remarked. “I couldn’t just say, ‘Well, I’ll only go out once a week.’ I thought the way to the next stage of my life was to leave town.”

In 1984 Arianna did, beginning an initial sojourn in Los Angeles. She made progress on the book and reconnected with someone she’d met years earlier in London, the oil heiress Ann Getty. The two became friends, and in 1985 Getty—believing it was time for Arianna to act on the conviction that had brought her to America, the desire to have children—invited her to her home in San Francisco to meet a man the family knew from the oil business, Michael Huffington. A tall, blond 38-year-old, who also happened to be a Republican multimillionaire, Michael had grown up in Houston and had graduated from Harvard Business School. Although he had worked in his father’s Houston-based firm, Huffco, he still had about him the air of an unformed rich boy.

The 1986 New York wedding of Arianna Stassinopoulos and Michael Huffington was one of the society events of the year. It cost a reported $100,000 and was covered by 18 reporters and gossip columnists. Barbara Walters was a bridesmaid.

The first months of the Huffingtons’ marriage saw the couple shuttling between Houston and Washington, where Michael secured a minor job in the Defense Department and Arianna resumed work on her biography of Picasso.

To say that Picasso Creator and Destroyer, which was finally published in 1988 was critically reviled doesn’t begin to describe the opprobrium heaped on it. The book, which drew extensively on Huffington’s interviews with Francoise Gilot, a woman who had come to loathe the great painter, presented Picasso almost exclusively as a brutalizing monster, and the reviews were scathing. “There is no sign in the 558 pages of Picasso: Creator and Destroyer,” wrote Robert Hughes in Time, “that Huffington has given a day’s close thought to Picasso’s art—or anyone else’s. To her, Picasso is mainly interesting as a celebrity … Huffington’s grasp of Picasso’s work … is so sketchy as to border on the sophomoric—on the few occasions it rises above freshman level.”

True to her Cambridge training as a debater, Huffington counterattacked, accusing the art establishment of denigrating her book in an effort to protect the reputation of one of its own. Her line of argument did not gain traction. Still, there were compensations, among them $500,000 from the producer David Wolper, who made Picasso: Creator and Destroyer the basis for a television movie.

Regardless of Huffington’s growing disillusionment with conservatives, she didn’t initially let on in public—much to her professional advantage.

On the eve of the Picasso fiasco, Arianna and Michael had moved to Santa Barbara with the intention of starting a political career for Michael. She remembers her years in the town fondly. There was the lovely Italianate house on Rivenrock Road in Montecito, and more meaningful, the births of her daughters. “That was like an incredibly beautiful time in my life,” she says, “because that is where I became a mother.”

Huffington may view her years in Santa Barbara through a maternal lens, but many of the town’s residents remember the interlude differently. “It was like a bad dream we woke up from, and we’re glad they’re gone,” says Nick Welsh, writer of the widely read “Angry Poodle Barbecue” column in The Santa Barbara Independent.

The continuing animus in Santa Barbara against the Huffingtons springs from the feeling that the couple essentially snookered the town. Michael introduced himself to Santa Barbara by writing checks to a number of local charities. Arianna wooed various society figures. In 1992, Michael announced that he was challenging longtime congressman Bob Lagomarsino in the Republican primary. Thanks to a shrewd decision on Michael’s part to embrace a pro-choice position on abortion, he succeeded in defeating the legislator in the primary and went on to win the general election. By every account, once Michael reached Washington, he showed little interest in representing the concerns of Santa Barbara. The Independent began referring to him in print as the “alleged Congressman.”

The suspicions that the Huffingtons regarded Santa Barbara only as a stepping-stone were borne out in 1994, when Michael declared his candidacy for the United States Senate. Spending $29.4 million of his own fortune, Michael ran neck and neck with Democratic nominee Dianne Feinstein almost to the wire. Then disaster struck, and all of it could be laid at the feet of Arianna. First, the Los Angeles Times published several pieces in which former members of the Movement of Spiritual Inner Awareness accused John-Roger of being a cult leader (which he denied) and identified Arianna as being one of his key adherents. Arianna responded by saying she’d cut all ties to the organization and become a born-again Christian. Hard upon the news about John-Roger, the Times broke a second and even more damaging story: Despite her husband’s vocal support for Proposition 187, the anti-illegal alien measure, Arianna employed an illegal alien as her nanny. Feinstein triumphed by a narrow 2 percent margin.

Although Michael lost in California, Republicans elsewhere around the nation won in astounding numbers, and Newt Gingrich was elevated to Speaker of the House. Suddenly, being conservative was sexy, and Arianna and Michael began spending most of their time in Washington. “I was raising money, helping in different ways, with at-risk children,” she says. “The dinners and meetings at the house were around that. My interest was to get the private sector to close the gap between the rich and poor.” The affairs, however, more than just drab discussions of policy. They were lavish, and invitations were coveted. Arianna had become hostess to the Republican takeover of Congress. “She was just glowing,” says Jeff Eisenach, her friend from those days. “Bright and magnetic and charismatic, and she was extremely taken with Newt Gingrich and taken with his ideas.”

According to the comedian Al Franken, Arianna left the Republican Party all because he didn’t want to sit with sex therapist Dr. Ruth Westheimer at the 1995 White House Correspondents’ Dinner. When Franken got an advance look at the seating chart and noticed that Arianna was also at the table, he requested that he instead be placed next to her. Despite loathing her politics, he wanted to meet her.

During the course of the evening, Huffington introduced Franken to a number of Republican notables, all of whom he disparaged as soon as they were out of earshot. After she presented him to the man of the moment—Speaker Gingrich—he remembers telling her: “Look, I can’t believe you’re buying this. He doesn’t give a shit about poor people. He is a terrible, terrible man.”

“There’s no question that Al and I really hit it off, even though we didn’t agree politically at the time,” recalls Huffington. “He exposed me to a lot of the hate-filled right-wing talk.”

For Huffington, this was the beginning of a crisis of faith. Slowly, she began to realize that her Republican friends were not who she thought they were and that her assumption that the private sector could do the work of government when it came to social justice was erroneous. “I tried to engage wealthy people in giving a lot to non-profits,” she says. “I tried for this issue to be taken seriously, because most of the charitable giving in this country doesn’t go to fighting poverty. It goes to fashionable museums. I basically stopped being a Republican when I realized that you couldn’t do it that way.”

Regardless of Huffington’s growing disillusionment with conservatives, she didn’t initially let on in public—much to her professional advantage. Indeed, her role as a Republican provocateur opposite new friend Franken on Politically Incorrect’s “Strange Bedfellows” segments during the 1996 national conventions inaugurated her career as a television and radio commentator. The sketches, in which Huffington and Franken lay in bed while exchanging views on everything from the candidates to erectile dysfunction, showed that the woman who’d been portrayed as evil and manipulative during her husband’s senatorial race had a sense of humor.

Despite her success as a television personality, Huffington’s life was in flux. Not only was she questioning her political identity, but her marriage was in trouble. In 1997, the same year she moved to Los Angeles for good, she and Michael divorced. There had long been rumors that Michael was gay, and in 1998 Arianna’s private pain became public. She received a phone call from Washington Post reporter Howard Kurtz. Michael, he told her, had come out in the pages of Esquire as a bisexual.

A brief but fascinating period in which Huffington gave strong indications of becoming an independent thinker followed the divorce. Although she was no longer a Republican, neither was she really a Democrat. When the Monica Lewinsky scandal broke, she created a Web site calling on Bill Clinton to resign. The zenith of Huffington’s phase as a political maverick occurred in 2000, when she organized the Shadow Conventions, which she conceived of as alternatives to the Republican and Democratic affairs. At Huffington’s gatherings, scholars and government officials debated a wide range of issues—the war on drugs, income inequality, campaign finance reform—too often overlooked by both parties. It was also in 2000 that Huffington published her first and best political book. How to Overthrow the Government is well constructed and cogently argued. In it, Huffington takes on both George W. Bush and Al Gore—the year’s presidential nominees—while building cases against many American institutions, among them the one she lives by: the media. She was that rare thing among the country’s commentariat—unpredictable. “She was a redheaded Mr. Smith,” says The Nation’s Marc Cooper. “It was a great position to be in.”

Whatever signs Huffington initially gave of sticking to the political center, by the time she announced her candidacy for governor of California in the 2003 recall election, she had moved to the left. Her involvement in the Detroit Project with Laurie David and the others—with their penchant to chastise the gas-guzzling fallen, even as they, the chosen, jetted above the flyover states in Gulfstreams—was all the proof one needed.

It is a lovely late July afternoon, and Huffington, a glass of iced lemon water in hand, sits on the sofa in the library of her Brentwood home. With its floor-to-ceiling bookcases, beamed ceiling, and paper-strewn desk, the room looks like the athenaeum of a well-read and well-heeled writer, which, on one level, it is. In truth, however, the library serves as the command and control center for Huffington’s multifaceted political, journalistic, and social enterprises. Behind a railed loft at one end of the space, a concealed door—on which hangs a painting of two red-frocked cardinals—opens into a hidden chamber. There the researchers who supply the facts for Huffington’s writings and the assistants who schedule speaking engagements and dispatch invitations to her salons hunch over computer terminals and answer incessantly ringing phones.

The operation gives off the slightest whiff of a boiler room, and no wonder. With Huffington hosting at least two dinners or soirees a month, churning out her weekly column, appearing on brief notice on half a dozen cable news shows (she was ubiquitous during the July flap raised by Schwarznegger’s “girly men” crack about California legislators and again following New Jersey governor James McGreevey’s August declaration that he is gay), and attending benefits or campaign rallies almost nightly, there is a daunting amount of work to be done. Typically, four employees labor full-time. During periods when Huffington is producing a book, that number increases, as she imports various journalists and farms out research to help her meet deadlines. Occasionally staffers have complained about getting “ground up,” but the atmosphere is predominantly congenial. Arianna’s sister, Agapi, who keeps an office farther back in the house and just published a book titled Gods and Goddesses in Love, frequently pads in to offer workers a bit of food from the kitchen.

To spend several hours talking to Huffington is to experience both her charm and her evasiveness. She is winning and gracious. She smiles often and possesses a forthright gaze, but these expressions, far from creating intimacy, erect a kind of dazzling barrier. There are matters she simply won’t talk about, foremost among them her ex-husband. Her rationale, that any such conversation might hurt their daughters, is persuasive. Yet she is equally chary about other inquiries. Friends, romantic entanglements, or anything that touches on her emotional life—all are off limits.

She is also unwilling to look at the more painful moments that her many transformations have wrought. For instance, when asked about some of the nasty things said about her during her years in Santa Barbara, she says, “I’m going to be very honest with you. I can’t recall it.” In this, Huffington, who like her sister is the author of a tome on the Greek gods, is emulating her favorite pagan deity, Hermes. “His whole thing is that you’re not caught in a particular moment,” she says. “You experience it good or bad, and then you move on.”

This is not to say that all subjects are taboo. Huffington talks glowingly about her daughters’ accomplishments. She will also speak about John-Roger, who she says is back in her world—if he was ever gone. Only two nights earlier, she confides, she’d hosted a dinner for the guru, meaning that he’d supped in the same room where the next morning Howard Dean breakfasted. “I love his work,” Huffington says of John-Roger. “I find it of tremendous value—his books, his tapes, his seminars. He’s been of tremendous importance to my life and continues to be. A lot of the stuff that’s been written is completely false. His teaching is simple and basic. It’s about recognizing that you’re a spiritual being and not just a material being.”

Yet just that quickly, the fortifications go back up. To the question “What do you want in life?” Huffington replies, “I want George Bush defeated.” On the off chance she misunderstood, the question is rephrased. But she understood it the first time. “It’s not just me, but you can talk to a lot of people who have the same sense of foreboding I have about what four more years of George Bush would mean. And you can talk to a lot of people who are dedicating their lives to John Kerry’s election.”

Huffington’s utility in the 2004 campaign is, like so much about her, a topic of dispute. A longtime observer who wishes her well laments: “The world of Hollywood liberals is a good social base but a shitty political base. If you want to be serious about politics, you don’t give a fuck what Warren Beatty or Laurie David think. Real change doesn’t come from Hollywood.” Those to the right of Huffington are even less impressed, dismissing her, in the words of Christopher Hitchens, as a caricature “from the Michael Moore playbook.” Huffington’s defenders, of course, disagree. Donna Bojarsky, a liberal L.A. political consultant, terms Huffington “an articulate spokesman and a doer. I’d rather have her on our side.”

But such matters may be beside the point, for as her role as salonista bears out, Huffington’s persona suggests something else. Though she presents herself as a commentator and an activist, what she really has become is a liberal priestess, a political Aimee Semple McPherson. Like McPherson, who dominated the spiritual life of Los Angeles in the 1920s, she has given her detractors ample ammunition to use against her. But also like McPherson, she possesses a devoted flock. Her Angelus Temple is, in fact, the city’s Westside.

On a midsummer Sunday, Huffington—again attired in green and black and carrying a bulky, Loro Piana bag stuffed with notebooks and a BlackBerry—enunciates the faith over and over. Starting at a “Mommies for Kerry” event at a West Hollywood park, then at a Southern California Political Action Group gathering at the headquarters of the Los Angeles Psychoanalytic Society, and once more at a home high above the ocean on Spoleto Drive in Pacific Palisades, she gives the same sermon. First she paints a portrait of Hell, with George Bush, First Lady Laura Bush (“a Stepford wife”), Vice President Dick Cheney, and the cabinet members as demons “appealing to our baser instincts.” Next she introduces the savior, John Kerry, “who appeals, as Lincoln put it, to our better angels.” The sides defined, she calls on the congregation to renounce darkness. “Idealism,” she declares, “is the sleeper issue in this campaign.” Then she brings home the message by bearing personal witness.

To see her standing at a microphone set up in front of striped pool furniture arranged amid lavender plants and lemon trees as the sun glints off her red hair and the surf pounds below only makes the story more intoxicating. “I have been on a journey,” she tells the gathering of wine-sipping supplicants in Pacific Palisades. “As you know, I used to be a Republican. Have you forgiven me?”

One voice shouts “No!” but Huffington presses ahead. “Well, the statute of limitations is up. It’s been since 1996 that I was a Republican. Back then Dennis Miller was a liberal and still funny. Michael Jackson was still black. And Saddam Hussein was still a friend of Dick Cheney.”

At that there is applause and a chorus of yeses, for she is articulating what for numerous Angelenos passes as holy writ: Through luck, talent, or even hard work, a person can be born anew—not only that, can be born anew into the Democratic faith. If this is so, it follows that the country itself can be transfigured. As long as Huffington continues to preach such homilies, the faithful will not question what came before or worry about the continuing contradictions, many of which they share. They will instead worship her.

[Photo Credit: By Photograph taken on September 11, 2003 by Minesweeper, c/o Wikimedia Commons]